Source: Link

CORRIVEAU (Corrivaux), MARIE-JOSEPHTE, known as La Corriveau; b. and baptized 14 May 1733 at Saint-Vallier, near Quebec, daughter of Joseph Corriveau, a farmer, and Marie-Françoise Bolduc; m. first on 17 Nov. 1749 Charles Bouchard, a farmer, who was buried on 27 April 1760 and by whom she had three children; and secondly on 20 July 1761 Louis Dodier, a farmer; died on the gallows at Quebec, probably on 18 April 1763.

There is scarcely any woman in all of Canadian history who has a worse reputation than Marie-Josephte Corriveau, generally called La Corriveau. This wretched woman died more than two centuries ago, but she continues to haunt the imagination. People still talk of her, of her crimes, real and fictitious. On 15 April 1763 she was condemned to death by a court martial for murdering Louis Dodier, her second husband, during the night of 26–27 Jan. 1763. This murder gave rise to two sensational trials before a military tribunal which met in one of the rooms of the Ursuline convent in Quebec and was composed of 12 English officers and presided over by Lieutenant-Colonel Roger Morris. The reports of these trials, discovered in London in 1947, allow us to establish the facts quite precisely and to separate them from the legend which grew up about them.

The first trial, which began on 29 March 1763, ended on 9 April with the death sentence for Joseph Corriveau, who was found guilty of the murder, and the sentencing of his daughter, Marie-Josephte, to be flogged and branded. But these sentences were not carried out because Joseph Corriveau’s confession – made after sentence had been pronounced on the advice of his confessor, the Jesuit superior Augustin-Louis de Glapion* – revealed his daughter as the sole guilty person and indicated that the crown attorney, Hector-Théophilus Cramahé*, had erred in his charge and his interpretation of the facts. His error was due to the fact that he accepted the testimony, contradictory as it happened, of Joseph’s niece, Élisabeth-Marguerite (Isabelle) Veau, dit Sylvain, that of a neighbour, Joseph Corriveau, the accused man’s homonym, which was, at least on the surface, overwhelming, and finally that of another neighbour, the talkative and imaginative Claude Dion. It was the contradictions in the evidence that the defence lawyer, Jean-Antoine Saillant, had tried to bring out in his pleading.

The court met again on 15 April to hear Marie-Josephte’s confession, in which she declared that she had killed her husband by hitting him on the head twice with an axe while he was sleeping. A new sentence, pronounced the same day, stipulated that Marie-Josephte would be hanged and that, in conformity with English law (Great Britain, Statutes, 25, Geo. II, 1752), her corpse would be exposed in chains for an indefinite period. The execution took place on the Buttes-à-Nepveu, near the Plains of Abraham, probably on 18 April 1763, and the iron cage, which was set up at Pointe-Lévy (Lauzon), remained in sight of passers-by until at least 25 May, when an order from the governor, James Murray*, authorized its removal. As for Joseph Corriveau, he was discharged with a certificate of innocence, as was his niece, Isabelle Sylvain, who had been accused of perjury at the first trial. His pardon received royal assent from George III on 8 August of that year.

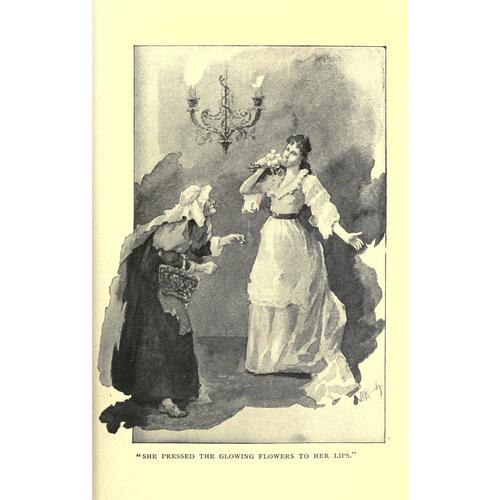

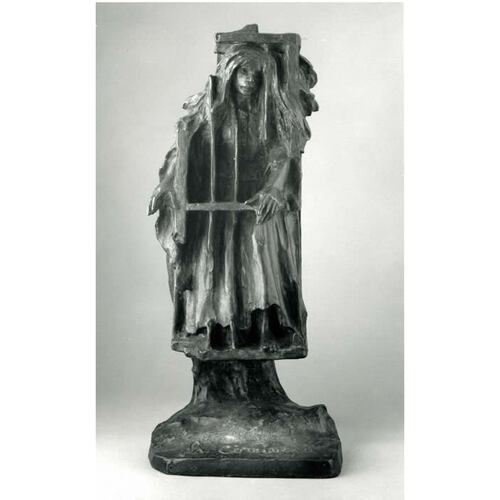

All these unusual facts and others still, such as the discovery of the iron cage in the cemetery of Lauzon around 1850, struck people’s imaginations. They were transformed into deep-rooted legends that are still recounted in oral tradition and inspired several fantastic tales which have been cleverly used by some Canadian writers. In Les Anciens Canadiens (Quebec, 1863) Philippe-Joseph Aubert* de Gaspé brought out in particular the nocturnal appearances of La Corriveau in her cage, begging a belated habitant on the road to Beaumont to take her to the sabbath of the will-o’-the-wisps and witches on the Île d’Orléans. After Sir James MacPherson Le Moine* in his article “Marie-Josephte Corriveau, a Canadian Lafarge” in Maple Leaves (Quebec, 1863), William Kirby*, in his novel The Golden Dog (New York, 1877), made La Corriveau into a professional poisoner, a direct descendant of the famous Catherine Deshayes, called La Voisin, who was hanged in Paris in 1680. Several other writers and historians, among them Louis-Honoré Fréchette* in his article “Une Relique,” in Le Monde Illustré (Montreal), 7 May 1898, and Pierre-Georges Roy* in “L’Histoire de La Corriveau,” Cahiers des Dix, II (1937), 73–76, have told La Corriveau’s story, without succeeding however in completely separating the true facts from anachronistic fantasies or legendary and romantic details. There is, for example, a lack of agreement on the number of murders – between two and seven – which are attributed to this wretched woman and on the different means which she used to carry them out. La Corriveau has also inspired artists: the sculptor Alfred Laliberté* made a remarkable bronze which is in the Musée du Québec portraying a haggard young woman bent under the weight of fatality and the cage in which she is imprisoned.

An exhaustive bibliography listing all manuscript and printed sources, reference works, and studies will be found in two articles by Luc Lacourcière: “Le triple destin de Marie-Josephte Corriveau,” Cahiers des Dix, XXXIII (1968), 213–42; “Le destin posthume de la Corriveau,” Cahiers des Dix, XXXIV (1969), 239–71.

Cite This Article

Luc Lacourcière, “CORRIVEAU (Corrivaux), MARIE-JOSEPHTE, known as La Corriveau,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 3, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/corriveau_marie_josephte_3E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/corriveau_marie_josephte_3E.html |

| Author of Article: | Luc Lacourcière |

| Title of Article: | CORRIVEAU (Corrivaux), MARIE-JOSEPHTE, known as La Corriveau |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 3 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1974 |

| Year of revision: | 1974 |

| Access Date: | December 29, 2025 |