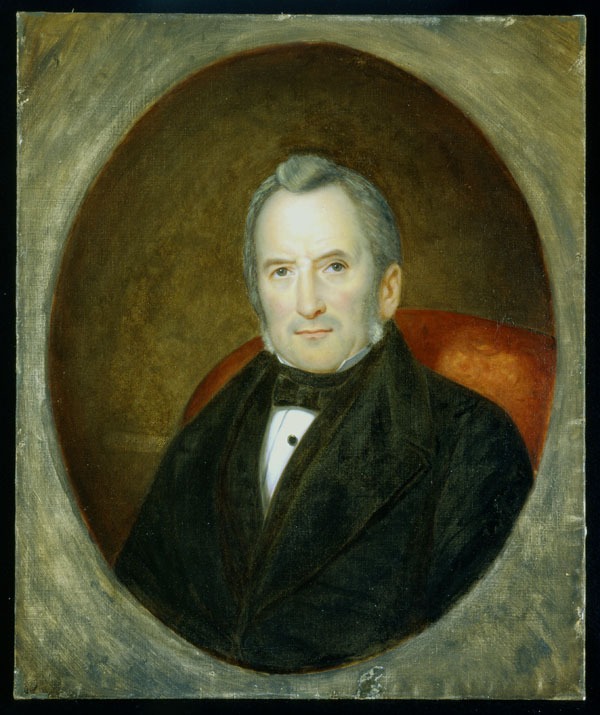

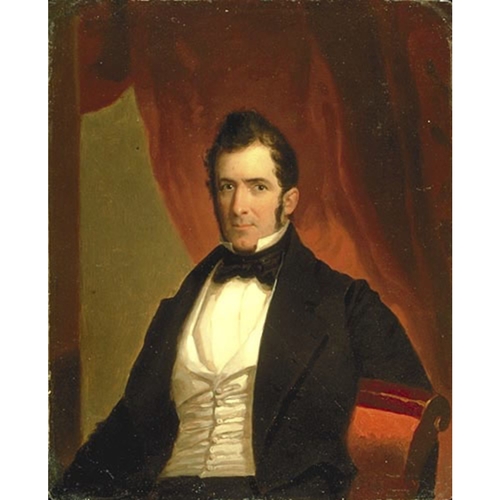

FARIBAULT, GEORGES-BARTHÉLEMI, lawyer, public servant, and bibliographer; b. 3 Dec. 1789 at Quebec, son of Barthélemi Faribault, merchant and later notary, and Marie-Reine Anderson, whose father was one of Fraser’s Highlanders; d. 21 Dec. 1866 at Quebec.

Georges-Barthélemi Faribault probably spent some years at John Fraser’s school at Quebec, and then received a secondary education interrupted from time to time. He trained in law in the office of Jean-Antoine Panet* and was licensed to practise law on 15 Dec. 1810.

An official of the House of Assembly of Lower Canada from the summer of 1812 on, Faribault became a lieutenant in the 6th battalion of light infantry on 20 March 1813, and in 1815 was appointed clerk of committees and papers (parliamentary archives). On 19 June 1821 he married Marie-Julie, daughter of Joseph-Bernard Planté*, a notary and mha for the county of Hampshire (Portneuf) from 1796 to 1808. They were to have three children: the first two died in infancy; the youngest, Georgina-Mathilde, married the painter Théophile Hamel in 1857. Faribault was already the third most senior officer in the house when he was appointed translator into French on 3 Dec. 1828. Then on 16 Nov. 1835 he became assistant clerk of the house, a post he held until his resignation on 9 May 1855.

In 1830 Faribault, who was familiar with legislative documents, accustomed to indexes, registries, and reference works, and interested in the activities of the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec, which had been founded in 1824, devised plans for collecting and cataloguing works on North America and particularly Canada. From 1832 on, he corresponded regularly with the Montreal antiquarian Jacques Viger*. On 14 Sept. 1835 he commemorated the landing of the native of Saint-Malo, Jacques Cartier*, by unveiling a monument, an initiative which put him in contact with Europe as did the purchase of Canadian books in Paris and London. Honorary librarian of the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec and adviser to Étienne Parent*, the librarian of the assembly, Faribault examined historical works, biographies, bibliographies, historical dictionaries, and booksellers’ catalogues. Throughout 1836 he was corresponding with Viger, when the latter was minutely annotating and completing the manuscript of Faribault’s Catalogue d’ouvrages sur l’histoire de l’Amérique, et en particulier sur celle du Canada. . . . This first Canadian bibliography appeared in 1837. It was designed “to be of use to those who might feel disposed to write a fuller history of Canada than any of those currently available”: William Smith*’s history printed in 1815 and published in 1825, the five abridged volumes (1832–36) of protonotary and pedagogue Joseph-François Perrault*, and the first part of Michel Bibaud*’s Histoire du Canada (Montréal, 1837), all of which went beyond the period covered by Pierre-François-Xavier de Charlevoix*’s history (1744).

This Catalogue of printed works, which published the results of the continued collection of material for the library of the house, does not, however, account for the interest increasingly being taken in official archives and historical manuscripts. Already Denis-Benjamin Viger in England, and Abbé John Holmes* in France (1836–38), had become copyists, before changes in the location of parliament after the union made the need for inventories and measures to protect the parliamentary archives more evident, and led the House of Assembly to create special committees (1845–47) on the state of the archives, a subject on which Faribault reported in September 1847. The Literary and Historical Society of Quebec, which was subsidized by the government and presided over by Faribault in 1844 and from 1849 to 1859, began to publish manuscripts. In 1842 it had received offers of copies of documents from the French archivist Pierre Margry, and it sent Andrew William Cochran*, a judge of the Court of Queen’s Bench, to make copies at Albany, N.Y. He was followed there, thanks to steps taken by Faribault, by Félix Glackmeyer, who was commissioned by the government to transcribe (November 1845 – March 1846, summer 1846) the collection of documents relating to the French colonial period that had been gathered by John Romeyn Brodhead.

Faribault, a diligent and tireless researcher, was in these years sought out frequently for advice and opinion. Jacques Viger continued to suggest subjects of research to him; the American historian George Bancroft, on the recommendation of Louis-Joseph Papineau*, visited him in 1837. Faribault corresponded with John Neilson*; on 21 Nov. 1848 he briefed Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine and drew his attention to the risk that “50 cases containing the files or documents of the different sessions of this legislature from 1791 to 1837” might be destroyed. He wrote to the mayor of Saint-Malo, France, in 1843 when the Literary and Historical Society was publishing Cartier’s Voyages . . . , corresponded with the philanthropist Nicolas-Marie-Alexandre Vattemare (1841–47), and ensured the exchange of legislative documents between France, the United States, and Canada; he carried on all these initiatives in collaboration with Adolphe de Puibusque, the French literary critic, writing and visiting him in Canada and France.

During the riot in Montreal on 25 April 1849, which Faribault termed “outrage and infamy,” the parliament buildings were burned, and the libraries and archives of the two legislative houses were destroyed. To attempt to repair “the irreparable,” the government sent Faribault on a European mission as an agent and special delegate to form a new parliamentary and national library. From 3 Oct. 1851 to 3 July 1852, in London and Paris, with a credit of £4,400, Faribault bought English and French volumes, visited ministries, and solicited gifts while distributing a few Canadian publications, and through Margry ensured that a plan for transcribing documents relating to New France was carried out (1852–55).

On 1 Feb. 1854, two years after this work of reconstructing the collection, the parliamentary library was again destroyed by fire. Jacques Viger confided at that time to Faribault: “Your misfortune [is that] people are more conscious of you in this than of the country.” On 9 May 1855, after 43 years of service and the grant of an annual pension of £400 until his death, Faribault resigned. It was at the very time of the celebrated voyage from France of La Capricieuse, commanded by Paul-Henry de Belvèze*, to be followed by the establishment of a French consulate at Quebec in 1859. While in retirement, Faribault presided again over the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec (1858–59), and for two years prepared the setting up of a monument in commemoration of Montcalm*; this was unveiled at Quebec on 13 Sept. 1859, 100 years after the defeat on the Plains of Abraham. Faribault, who had been a widower since 1852, died in December 1866, a few months after the historians François-Xavier Garneau and Abbé Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Ferland. By this time the government was undertaking more and more systematically the reprinting of historical documents, and François-Marie-Uncas-Maximilien Bibaud*, Abbé Louis-Édouard Bois*, Abbé Charles-Honoré Laverdière*, and Father Félix Martin* were continuing the historiographical tradition.

The patient labour of this “archaeologist,” a public servant of refined and aristocratic courtesy, who spoke in 1835 of the “reign of law and order” and in 1848 of “Europe in flames,” warrants an attention not thus far paid to his initiative in collecting documents which were essential for the beginnings of historiography in Quebec, and also suggests an evaluation of the ideological implications deriving from the fact that a generation of polygraphers and historians were linked socially with the political and religious powers. A bibliographer “to whom historical science is indebted for such eminent services,” Faribault, through books, booksellers, and archivists, had found the way to a free cultural exchange.

Georges-Barthélemi Faribault left his personal collections to the Séminaire de Québec and to Université Laval; Father Charles-Honoré Laverdière was his executor. These papers can be consulted at present at ASQ, in the Fonds Viger-Verreau, Saberdache bleue, and carton 60, liasses 12–29; in Polygraphie, VI, 81A. Other Faribault papers are located at ANQ-Q.

The PAC also has copies of documents from Albany and Paris relative to New France, which were collected through Faribault’s efforts (MG 8, A1). Letters from Faribault are also found in the Neilson collection (MG 24, B1), in the Denis-Benjamin Viger papers (MG 24, B6), and in the La Fontaine papers (MG 24, B14). Further interesting information on Faribault can be found in the P.-G. Roy papers (MG 30, D58), and the F.-J. Audet manuscripts (MG 30, D62, 12, pp.662–63). Another important source is the Vattemare collection in the New York Public Library. Official documents relating to Faribault’s appointments and to his trip to Europe in 1852 are in the Journals of the House of Assembly of Lower Canada (1812–37) and of the Legislative Assembly of the province of Canada (1841–66).

Faribault was the author of Excursion à la Côte Nord, au-dessous de Québec; nouvel établissement aux Escoumains, anciens vestiges sur l’île aux Basques (Québec, 1849), and he compiled Catalogue d’ouvrages sur l’histoire de l’Amérique, et en particulier sur celle du Canada, de la Louisiane, de l’Acadie, et autres lieux; avec des notes bibliographiques, critiques et littéraires (Québec, 1837).

ANQ-Q, État civil, Catholiques, Notre-Dame de Québec, 3 déc. 1789, 19 juin 1821. Archives du séminaire de Nicolet (Nicolet, Qué.), Succession Bois, IV, 3:44 (23 mars 1861). Bibliothèque de la ville de Montréal, Salle Gagnon, mss, Pierre Margry, 31 mars 1855. BUM, Coll. Baby, Doc. divers, M1394–96. New York Public Library, Alexandre Vattemare, Copypress letterbooks, 9v., no.3. PAC, RG 9, 1, A3, 12, pp.18–19; RG 68, 99, p.234. Lettres à Pierre Margry de 1844 à 1886 (Papineau, Lafontaine, Faillon, Leprohon et autres), L.-P. Cormier, édit. (Québec, 1968). Le Canadien, avril–mai 1849. La Minerve, 17 juin 1844, 3 mai 1847, févr. 1854. Montreal Transcript, 10 April 1852. Quebec Gazette, September 1835.

Catalogue de la bibliothèque du parlement (2v., Québec, 1857–58), II, 1448. Catalogue of books in the library of the Legislative Assembly of Canada (Montreal, 1846). P.-G. Roy, Fils de Québec, III, 45–47. H.-R. Casgrain, Faribault et la famille de Sales Laterrière (Montréal, 1912). The centenary volume of the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec, 1824–1924, ed. Henry Ievers (Quebec, 1924). Guy Frégault, “La recherche historique au temps de Garneau (la correspondence Viger-Faribault),” Centenaire de “l’Histoire du Canada” de François-Xavier Garneau; deuxième semaine d’histoire à l’université de Montréal, 23–27 avril 1945 (Montréal, 1945), 371–90. Notice sur la destruction des archives et bibliothèques des deux chambres législatives du Canada, lors de l’émeute qui a eu lieu à Montréal le 25 avril 1849 (Québec, [1849]). P.-G. Roy, La famille Faribault (Lévis, Qué., 1913). N.-E. Dionne, “Historique de la bibliothèque du parlement à Québec, 1792–1892,” RSC Trans., 2nd ser., VIII (1902), sect.i, 3–14. J. F. Kenney, “The public records of the province of Quebec, 1763–1791,” RSC Trans., 3rd ser., XXXIV (1940), sect.ii, 87–133. W. K. Lamb, “Seventy-five years of Canadian bibliography,” RSC Trans., 3rd ser., LI (1957), sect.ii, I–II. Fernand Ouellet, “L’histoire des archives du gouvernement en Nouvelle-France,” La Revue de l’université Laval (Québec), XII (1958), 397–415. Élisabeth Revai, “Le voyage d’Alexandre Vattemare au Canada: 1840–1841; un aperçu des relations culturelles franco-canadiennes: 1840–1857,” RHAF, XXII (1968–69), 257–99. J.-E. Roy, “Les archives du Canada à venir à 1872,” RSC Trans., 3rd ser., IV (1910), sect.i, 57–123.

Cite This Article

Yvan Lamonde, “FARIBAULT, GEORGES-BARTHÉLEMI,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/faribault_georges_barthelemi_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/faribault_georges_barthelemi_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Yvan Lamonde |

| Title of Article: | FARIBAULT, GEORGES-BARTHÉLEMI |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | April 29, 2025 |