Source: Link

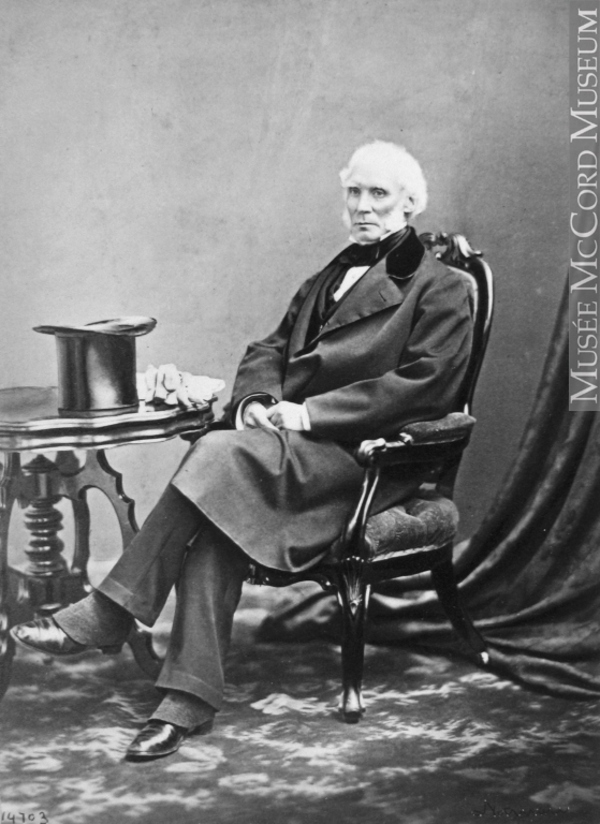

MOFFATT, GEORGE, businessman and politician; b. 13 Aug. 1787 at Sidehead, Weredale, Durham, England; m. first in 1809 an Indian whose name is not known (they had one son, Lewis), and secondly Sophia MacRae, by whom he had three sons; d. 25 Feb. 1865 in Montreal, Canada East.

After some schooling in London, George Moffatt came to Canada in 1801 at the age of 14 under the sponsorship of Montreal merchant John Ogilvy*. Further schooling with William Nelson at Sorel preceded his entry into his patron’s firm, Parker, Gerrard, and Ogilvy, a major component of the XY Company. He later left them to join the firm of McTavish, McGillivray, and Company, the principal partner in the rival North West Company, and took part in a number of trips to Fort William (Thunder Bay, Ont.). In 1811 Moffatt set up his own firm in partnership with Alexander Dowie, a nephew of Sir Alexander Mackenzie*, which soon merged with Parker, Gerrard, and Ogilvy. After several changes the firm became known as Gillespie, Moffatt, and Company with Moffatt the principal Montreal partner and Robert Gillespie his associate in London. Although the firm became a major Montreal supply house for the fur trade, Moffatt was by no means totally committed to the North West Company; in 1809, while still working for McTavish, McGillivray, and Company, he was ready to join with Colin Robertson* in establishing an agency of the Hudson’s Bay Company in Montreal.

After serving briefly during the War of 1812 with the Montreal volunteers at Laprairie under Charles-Michel d’Irumberry* de Salaberry, Moffatt aided Robertson, still an officer of the HBC, in his expeditions of 1815 and 1816 to the Athabaska country. He was one of Robertson’s close friends and in 1819 put John McLoughlin*, a discontented wintering partner of the NWC, in contact with the HBC, thus paving the way for the coalition of the two great fur-trading companies in 1821 [see Edward Ellice]. In facilitating the merger Moffatt was betraying an already failing cause: the NWC was losing money and had sacrificed much prestige during its protracted squabbles with Lord Selkirk [Douglas*]. As a major Montreal merchant Moffatt no doubt wanted a number of things which, to his mind, the merger would accomplish, among them the settlement of the NWC’s debts, including some to Gillespie, Moffatt, and Company, and the elimination of competition and of generally chaotic conditions in the fur trade.

By 1821 Gillespie, Moffatt, and Company had become one of the major import-export houses of Montreal. It dealt in a wide range of imported manufactured goods, including groceries and dry goods and hardware, as well as the increasing volume of up-country staple commodities being shipped down the St Lawrence for foreign markets. The firm occupied large premises facing the Lachine Canal wharves, where it received its incoming shipments. Its affairs expanded substantially during the next decade and by the mid 1840s Gillespie, Moffatt, and Company received more seaborne goods than any other firm in Montreal, handling in 1845 alone the cargo of 15 foreign ships. By this time the company itself owned one large ship and was hiring several others each year to haul cargo overseas, much of it on consignment to Moffatt’s British-based partners, Alexander and Robert Gillespie. A branch of the firm, Moffatt, Murray, and Company, was later opened in Toronto by Moffatt’s eldest son, Lewis.

Like most of his business contemporaries, Moffatt had many other interests besides his own firm. He was an investor in the Lower Canada Land Company (formed in 1825) and a Canadian representative of the British American Land Company which had vast holdings in the Eastern Townships. Moffatt had his own substantial land holdings in Lower Canada including an island in the St Lawrence opposite Montreal. One of Moffatt, Gillespie, and Company’s most important sidelines was insurance. The firm managed the Canadian branch of the Phoenix Fire Assurance Company which had had policies in the Canadas since 1804; by 1845, under Moffatt’s management, the company had policies for £285,000 in Montreal. In that year a special inspector was sent from London and reported favourably on Moffatt’s judgement in accepting risks in Montreal.

As a dominant figure in the city’s commercial life, Moffatt was keenly interested in increasing its metropolitan mercantilist strength. He was active in a large number of enterprises which promoted Montreal’s hegemony, including the Bank of Montreal of which he was a director from 1822 to 1835. He was also an early promoter of the pioneer Champlain and St Lawrence Railroad and a fervent promoter, major shareholder, and director of the St Lawrence and Atlantic Railroad; the latter, running 245 miles from Saint-Lambert opposite Montreal to Portland, Maine, was begun in 1845 and completed in 1853. His name was associated with many other ventures typical of the new economic activities emerging in the Canadas during the mid 19th century. He was a director of the Montreal Mining Company, established in 1847 to exploit the copper deposits on the north shore of Lake Huron, and a promoter of the Marine Mutual Insurance Company of Montreal in 1851, Molsons Bank in 1854, the Canada Marine Insurance Company in 1856, and the Montreal Steam Elevating and Warehousing Company in 1857. Businessmen’s clubs, where deals were often scouted or concluded, were a necessary adjunct to the commercial activity of a city, and Moffatt led in the formation of the exclusive St James Club in 1857. Other institutions reflecting Montreal’s Anglo-Saxon commercial class which received Moffatt’s support included the St George’s Society, the Mountain Boulevard Company, the Montreal Cemetery Company, St George’s Church, and McGill University.

The continuance of Montreal’s key position in the import-export trade of Canada depended heavily on the ability of its harbour to handle an increasing volume of commodities and ocean-going ships. However, Montreal’s commerce was severely hampered by high shipping costs since large ocean-going vessels could proceed up river only as far as Quebec, and there was a lack of adequate wharves. Along with fellow Montreal merchants, Moffatt sought to improve the harbour of Montreal and in 1830 had been designated chairman of the newly appointed harbour commissioners of Montreal. With his fellow members Jules-Maurice Quesnel * and Captain Robert S. Piper, he oversaw the erection of wharves at Montreal and initiated surveys of Lac Saint-Pierre to determine where the shipping channel should be dredged. Later, in the legislature, first as a member and in 1841 as chairman of a special committee, he was associated with efforts to deepen the channel. Moffatt had also been an original member of the Committee of Trade formed in 1822, and after it was reconstituted as the Montreal Board of Trade in 1842 was its president from 1844 to 1846; the question of harbour improvements occupied much of its time.

George Moffatt’s legislative career began in 1831 when he took a seat in the Legislative Council of Lower Canada and assumed the mantle of his predecessor John Richardson* as spokesman for Montreal businessmen. During the increasingly tense 1830s the actions of the Legislative Council in rejecting or severely amending bills sent up from the assembly exacerbated tensions. Moffatt was in large measure responsible for increasing this animosity by instituting in 1832 criminal charges against two Montreal newspaper editors, Ludger Duvernay* of La Minerve and Daniel Tracey* of the Irish Vindicator and Canada Advertiser, who had ridiculed the council. Their vindictive arrests and imprisonments set the stage for the violent election campaign in Montreal West in May 1832; Tracey, recently released from prison and now a popular hero, trounced the merchants’ candidate Stanley Bagg. Moffatt also had a hand in the tragic denouement to the election which took place on 21 May: as one of the magistrates of Montreal, he approached the garrison for assistance in keeping order at the polls and instructed the army to advance on a rioting mob; three persons were killed.

As the moral leader of the Lower Canadian English speaking community, Moffatt was one of the most active of the Montreal merchants who organized the “constitutionalists” of Montreal between 1832 and 1837. Although not as closely identified with the Constitutional Association of Montreal as John Molson* Jr or Peter McGill [McCutcheon*], Moffatt appears to have been a major behind-the-scenes-figure directing some of the most venomous attacks on French Canadians. He was probably one of the leading associates of Adam Thom* whose “Anti-Gallic letters” were published in the Montreal Herald during the autumn of 1835.

Moffatt and William Badgley*, a Montreal solicitor, went to London in the fall of 1837 to explain the position of the “British party” to the imperial government. In the aftermath of the Lower Canadian rebellion of 1837 Moffatt advocated to Colonial Secretary Lord Glenelg a moderate course in handling captured rebels, suggesting that only a few of the most serious offenders be banished. When Lord Durham [Lambton*] was appointed high commissioner of British North America in January 1838, Moffatt and Badgley provided him with a detailed memorandum outlining the major reforms they felt were necessary, including some which had been pursued unsuccessfully for decades by Lower Canadian merchants to create a more favourable business climate; a letter advising against the election of members of the Legislative Council was also provided. Moffatt accompanied Lord Durham to Canada and continued to offer advice on such matters as the disposition of prisoners. He also pressed for a legislative union with Upper Canada, which he considered was the best constitutional solution to the problems of Lower Canada. On 2 Nov. 1838 Sir John Colborne appointed Moffatt to the Special Council of Lower Canada following the suspension of the constitution. As a member of the executive of the Special Council he was one of Colborne’s principal advisers.

The arrival of Colborne’s replacement, Charles Poulett Thomson*, in October 1839 drastically altered Moffatt’s status on the council. In a letter to Colonial Secretary Lord John Russell in December 1840, Thomson, now Lord Sydenham, described Moffatt as “the most pig headed, obstinate, ill tempered brute in the Canadas . . . whom I shall certainly not put in the new Legislative Council” of united Upper and Lower Canada. If Moffatt was to have a significant voice in union politics he had no choice but to sit in the Legislative Assembly. He was elected, with Sydenham’s blessing, as one of the two members for the Montreal City riding in 1841. Moffatt had long supported union and it must have been with special pride that he sat in its first legislature. He resigned his seat on 30 Oct. 1843 to protest against the decision to move the capital from Kingston to Montreal, on the grounds that it was unfair to Canada West, but regained the seat in 1844, defeating Dr Pierre Beaubien* who had succeeded him the previous year.

Although Moffatt was never much at home in the assembly he was an assiduous member who was mindful of the interests of the Montreal English speaking business community. He introduced bills which originated in that community, including many from the Montreal Board of Trade, and which favoured its institutions, such as the Royal Institution for the Advancement of Learning and the High School of Montreal (but he also brought in bills on behalf of the Grey Nuns). He participated frequently in debates, especially in discussions on legislation affecting railways, usury laws, and McGill University. He served on several special committees during his six years in the house, including one in 1842 to consider the disposition of the Jesuit Estates.

Moffatt remained a conservative, but he now spoke with new-found moderation. He was far from being an anti-French reactionary; in the 1844–45 session he seconded Denis-Benjamin Papineau*’s motion favouring the reinstatement of French as an official language of debate and record in the Province of Canada and recanted earlier remarks in the assembly against the use of French. He also declared that he was prepared to support the payment of rebellion losses claims in Lower Canada. Civil disorder in Montreal and at Beauharnois during the early 1840s [see Frederick William Ermatinger] was of special concern to Moffatt, and he sought to have the police forces augmented and placed under the control of the executive in order to increase their effectiveness.

Moffatt was not a candidate in the 1847 elections. He might have felt that he had already made whatever contributions he could towards the establishment of a favourable climate for business in Canada through the legislative process. But changes in British imperial policy at the end of the 1840s provoked violent reaction among Montreal Tories, many of whom signed the Annexation Manifesto of October 1849. Moffatt, although he had flirted briefly with Montreal free traders in 1847, remained aloof from annexationism. Instead, he became president of the Montreal branch of the British American League, an association of Conservatives and Tories formed to debate the problems created by the sudden disappearance of a protected imperial market for Canadian staples. The league included Harrison Stephens*, Thomas Wilson, John Esdaile, John Gordon MacKenzie, James Mathewson, and William Spier, all established Montreal merchants. In a manifesto published in the Montreal Gazette on 20 April 1849 Moffatt’s group described themselves as “children of a monarchy, too magnanimous to prescribe, too great to be unjust.” Their concern was for the “prosperity of Canada and with it the nation of which it forms a part.” By using his extensive business and political influence throughout Canada, Moffatt hoped to undermine the annexationist menace by reconstructing a strong province-wide conservative organization. He visited Toronto and guided the sessions of the league’s convention in July 1849 in Kingston where resolutions were passed calling for a study of the possibility of uniting the British American provinces, for retrenchment in public expenditure, and for protection for home industry. In Moffatt’s opinion the resolutions demonstrated “that annexation had by no means captured the main forces of the tory-conservative party.” A second convention in early November received a report from a committee which had discussed the proposal for union with representatives of the other colonies. Debate also ranged over a number of current economic issues, including reciprocity, annexation, free trade, and the renewal of protection.

The league underlined the fundamentally loyal character of Canadian political conservatism, but it made no lasting contribution to the political life of Canada and soon disappeared. Moffatt also retired from active politics at this time to concentrate on business. His association with banking and railway ventures in the 1850s indicates that he was alive to the entrepreneurial opportunities in finance and transportation in this era of rapid economic growth and change. He devoted considerable attention to the affairs of the Church of England in Montreal, where funds were being collected for the erection of Christ Church Cathedral on Rue Sainte-Catherine.

A fervent empire loyalist to the end, Moffatt always publicly upheld the “British connection.” When he died in Montreal on 25 Feb. 1865, he was probably the last of the small group of Montreal businessmen whose careers stretched from the era of the fur trade to the age of steam railway and heavy industry. They were entrepreneurs in a period of transition, who possessed the remarkable flexibility and diversity that enabled them to move easily from fur to wheat, hardware, dry goods, banking, insurance, mining, railways, and land speculation within one generation. Of them all, George Moffatt was in many ways the most representative.

BUM, Coll. Baby, Doc. divers, G2, 1820–30. Conseil des ports nationaux (Cité du Havre, Montréal), Minute books, 22 Aug. 1846. McGill University Libraries, Dept. of Rare Books and Special Coll., ms coll., Corse family papers. PAC, MG 24, D11; RG 1, L3L, 126, 160–63; RG 42, I, 175, p.14. British American League, Minutes of the proceedings of the second convention of the delegates . . . (Toronto, 1849). Can., Prov. of, Statutes, 1847, c.67; 1849, c.164; 1851, c.202; 1856, c.124; 1857, c.178. Debates of the Legislative Assembly of United Canada. Documents relating to NWC (Wallace). Elgin-Grey papers (Doughty), I, 347, 411, 443. HBRS, II (Rich and Fleming). Macdonald, Letters (Johnson and Stelmack). Select documents in Canadian economic history, ed. H. A. Innis and A. R. M. Lower (2v., Toronto, 1929–33). [C. E. P. Thomson], Letters from Lord Sydenham, governor-general of Canada, 1839–1841, to Lord John Russell, ed. Paul Knaplund (London, 1931), 107. Montreal Gazette, 23 Jan. 1845, 27 Feb. 1865. Montreal Transcript, 21 April, 24 May, 14 July 1838. Morning Courier (Montreal), 16 May 1849. F.-J. Audet, Les députés de Montréal. Notman and Taylor, Portraits of British Americans, I, 113. Political appointments, 1841–65 (J.-O. Coté). G. Turcotte, Cons. législatif de Québec. C. D. Allin and G. M. Jones, Annexation, preferential trade and reciprocity; an outline of the Canadian annexation movement of 1849–50, with special reference to the questions of preferential trade and reciprocity (Toronto and London, [1912]). K. M. Bindon, “Journalist and judge: Adam Thom’s British North American career, 1833–1854” (unpublished ma thesis, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., 1972), 60ff. Careless, Union of the Canadas. Christie, History of L.C. E. A. Collard, Oldest McGill (Montreal, 1946); The Saint James’s Club; the story of the beginnings of the Saint James’s Club (Montreal, 1957). D. [G.] Creighton, The empire of the St. Lawrence (Toronto, 1956). R. C. Dalton, The Jesuits’ estates question, 1760–1888: a study of the background for the agitation of 1889 (Toronto, 1968). P. G. MacLeod, “Montreal and free trade, 1846–1849” (unpublished ma thesis, University of Rochester, N.Y., 1967), 114, 138–39, 166. Monet, Last cannon shot. Montreal business sketches with a description of the city of Montreal, its public buildings and places of interest, and the Grand Trunk works at Point St. Charles, Victoria Bridge, &c, &c. (Montreal, 1864), 103–7. Gustavus Myers, History of Canadian wealth (Chicago, 1914). C. W. New, Lord Durham; a biography of John George Lambton, first Earl of Durham (Oxford, 1929). Phoenix Assurance Company Ltd., First in the field ([Toronto, 1954]). Rich, History of HBC, II. Semi-centennial report of the Montreal Board of Trade, sketches of the growth of the city of Montreal from its foundation . . . (Montreal, 1893). Helen Taft Manning, The revolt of French Canada, 1800–1835: a chapter in the history of the British Commonwealth (Toronto, 1962). G. J. J. Tulchinsky, “Studies of businessmen in the development of transportation and industry in Montreal, 1837–1853” (unpublished phd thesis, University of Toronto, 1971), 466. Adam Shortt, “Founders of Canadian banking: the Hon. George Moffatt, merchant, statesman and banker,” Canadian Bankers’ Assoc., Journal (Toronto), XXXII (1924–25), 177–90.

Cite This Article

Gerald Tulchinsky, “MOFFATT, GEORGE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 6, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/moffatt_george_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/moffatt_george_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Gerald Tulchinsky |

| Title of Article: | MOFFATT, GEORGE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1976 |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | January 6, 2025 |