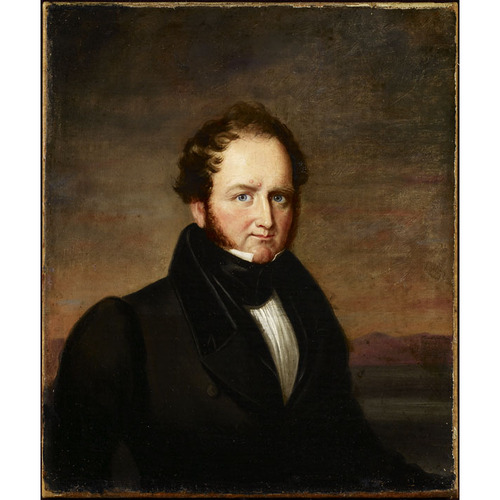

ROBERTSON, COLIN, fur trader, merchant, and politician; b. 27 July 1783 in Perth, Scotland, son of William Robertson, weaver, and Catherine Sharp; m. c. 1820 Theresa Chalifoux, and they had seven children; d. 4 Feb. 1842 in Montreal.

Colin Robertson was born into a hand-weaving family before the trade collapsed from the competition of factories. In his boyhood there seemed enough future in his father’s craft for him to become an apprentice weaver. Hudson’s Bay Company governor George Simpson*, who came to dislike him intensely, asserted in his “Character book” of 1832 that Robertson was “too lazy to live by his Loom”; he conjured up the image of a youth who spent his time reading novels and “became Sentimental and fancied himself the hero of every tale of Romance that passed through his hands.” Whether or not, as Simpson claimed, Robertson “ran away from his master,” it is certain that he did not finish his apprenticeship, abandoning hand-weaving and finding his way to New York, where he worked in a grocery store. There, Simpson stated, Robertson “had not sufficient steadiness to retain his Situation.” On the other hand, it seems evident that Robertson at this time gained enough experience in salesmanship to make him feel competent in later years to set up as a wholesale merchant in the intervals of his involvement in the fur trade.

There is no definite information about when Robertson came to the Canadas, but he entered the service of the North West Company as an apprentice clerk before the end of 1803. Two years later an HBC trader, William Linklater, reported that Robertson, with two NWC employees, caught up with him at Otter Portage (Sask.) and “means to keep us company until we arrive at Isle a la Crosse [Sask.].” Clearly Robertson had been deputed to travel close to HBC men on the Saskatchewan River and prevent their trading with the Indians.

In 1809 Robertson left the service of the NWC, partly, it appears, because of slowness in promotion after the Nor’Westers had absorbed the partners of the New North West Company (sometimes called the XY Company), and partly because of his difficulty in working with the irascible John McDonald* of Garth, with whom he once fought a duel. Contrary to Simpson’s belief that he was dismissed, the NWC’s letter to Robertson on his departure makes it clear that he was retiring from a post in which he had served with loyalty and competence. Still, he was already in touch with the HBC Chief Factor William Auld*, whom he had visited at Cumberland House (Sask.) in 1809 before retiring and who was convinced of the need for vigorous opposition to the NWC. During that visit, an understanding seems to have been reached, since, when Robertson sailed to England, he paid his fare with a loan from Auld, who also gave him an introduction to the London committee of the HBC.

On reaching London, Robertson found the HBC in a state of flux and re-organization. Lord Selkirk [Douglas*] and Andrew Wedderburn had become powerful shareholders and were changing the company in ways that made inevitable a more aggressive policy towards its trading rivals. Robertson immediately put forward a proposal that the company should turn to the attack by pushing its trade into the Athabasca country, then dominated by the Nor’Westers, and that it should do so by using Canadian voyageurs, recruited in Montreal and experienced in travelling and trading in the Indian country. He suggested the establishment of an agency in Montreal to organize such an expedition, and hoped to be placed in charge. The London committee was attracted by Robertson’s plan but did not find it immediately expedient, and on 21 Feb. 1810 rejected it, while offering Robertson employment. He wished, however, to join the company on his own terms, and left London for Liverpool, where he and his brother Samuel set up as general merchants and ships’ chandlers. In 1812 he went into a partnership with Thomas Marsh of Liverpool that was to last for about five years.

Although Robertson seemed to be planning a future outside the fur trade, he followed the rapid turn of events in the northwest; Selkirk’s establishment of the Red River colony (Man.) in 1812 across the Nor’Westers’ main trade routes had made a confrontation between the two companies unavoidable. When Robertson was summoned to London for a meeting with Wedderburn early in 1814, he went with a revised plan for the attack on the Athabasca country, which he submitted on 15 March. Having conserved its resources through retrenchment, the committee was now prepared for the expansion on which the company’s survival depended. As a feint, Joseph Howse* would be sent with a strong force to re-establish the fort at Île-à-la-Crosse, but the real expedition would be under Robertson. To compensate him for possible losses owing to his absence from business in Liverpool, the committee agreed that Marsh and Robertson should supply the HBC with any woollen or cotton goods it needed.

On 22 May Robertson sailed from Liverpool. The ship went in slow convoy for protection against French warships and privateers and was several times delayed by storms, so that he did not reach Quebec until 27 Sept. 1814. He hurried to Montreal and, posing as an agent of Selkirk selling land in the Red River colony, began to make arrangements for the first HBC expedition supplied from Montreal. He had missed a season, and it was not until 17 May 1815 that he eventually set out for the interior with 16 canoes, 160 voyageurs, and 3 former Nor’Westers he had persuaded to accompany him: John Clarke*, François Decoigne*, and Robert Logan*.

Robertson was, on the whole, well fitted for the enterprise. He knew the country for which he was bound; he also knew both the methods of the Nor’Westers and the personalities of the men with whom he would be contending. He was a braggart, but an audacious one: his favourite maxim was “When you are among wolves, howl!” A striking man, six feet tall, with a long aquiline nose, a crest of undisciplined red hair, and a fondness for quoting Shakespeare and drinking Madeira, he was generous, flamboyant, extravagant, and he cultivated these qualities when he was among the voyageurs on whom his success depended. “Glittering Pomposity,” he once remarked, “has an amazing effect on the Freemen, Metiss and Indians.” But he was genuinely courageous, willing to take risks, and aware of the advantage to be gained from anticipating his opponents. The same qualities tended at times to make him blind to danger, and he sometimes underestimated his enemies, but the fact that his Athabasca plan on the whole turned out so successfully and heralded the end of the NWC as an independent organization, suggests that he was far from the “frothy trifling conceited man” sketched by Simpson.

Even before Robertson got as far as Red River he found that the antagonism of the Nor’Westers towards Selkirk’s colony had peaked in open violence. Miles Macdonell*, first governor of Assiniboia, had been arrested by the Nor’Westers and transported to Lower Canada. The settlement had been burnt down, and Robertson met some of the dispossessed settlers on their way to the Great Lakes. He took them back with him, and at the request of James Bird* and Thomas Thomas* agreed to re-establish the colony, while on 4 Aug. 1815 his expedition was sent on to the Athabasca country under John Clarke. On 15 October Robertson seized the NWC’s Fort Gibraltar (Winnipeg), and, upon extracting from Duncan Cameron a promise that NWC depredations would cease, returned it to him. Robertson then rebuilt the HBC’s Fort Douglas (Winnipeg), which the rival traders had destroyed. He spent the winter on Red River, dealing forcibly with renewed threats from his opponents, and in March 1816 he again seized Fort Gibraltar. Despite such aggressive initiatives, Robertson’s relations with Robert Semple*, who had arrived in November 1815 as the new governor of Assiniboia, deteriorated badly. Semple’s concerns lay in provisioning the colony while Robertson was determined to blockade the rivers and prevent the Métis from supplying pemmican to the NWC brigades going west. Thoroughly upset, he left Red River on 11 June 1816, intending to return to England and his foundering business.

Robertson reached York Factory (Man.) early in July and, while awaiting a ship there, heard two pieces of news which suggested that his plans had come to nothing. As soon as he had left Fort Douglas, the Nor’Westers had stepped up their provocations against the Selkirk settlers, and on 19 June, at Seven Oaks (Winnipeg), Semple and about 20 of his men had been killed. Meanwhile, harassed by the Nor’Westers, Clarke’s expedition had ended in starvation and failure, and Clarke himself had been arrested by Samuel Black.

Robertson finally sailed for England on 6 October, but his ship was held in the ice of Hudson Bay and he wintered at Eastmain Factory (Eastmain, Que.) and Moose Factory (Ont.) until breakup. By March 1817 he had learned that he would be arraigned at Montreal on charges brought against him by the NWC for his seizure of Fort Gibraltar. He arrived at Montreal in August, resolved to clear his name, but within months he had also become deeply involved in planning his next assault on the Athabasca country. By refusing to accept bail and insisting on going to prison, he gained a trial in the spring of 1818 and was acquitted. He was thus freed for the Athabasca counter-attack which – considering the discontent among the wintering partners of the NWC – he believed might break its spirit. His English business had drifted into bankruptcy in his absence, but Selkirk agreed to guarantee it, and in the summer Robertson set out from Montreal with 10 canoes, 10 officers, and 100 voyageurs.

As he moved into the interior of Rupert’s Land, the survivors of Clarke’s ill-fated expedition joined him, so that by the time he left Lake Winnipeg he had 27 canoes and 190 men, including the liberated Clarke. Arrested by the persistent Samuel Black in October on charges of attempted murder and imprisoned in Fort Chipewyan (Alta), Robertson contrived to smuggle out messages to his men which encouraged them to resist the Nor’Westers. Then, in June 1819, when he was being taken out of the Athabasca country as a prisoner, he escaped at Cumberland House and returned to lead the HBC’s expedition into the interior later that year. He wintered at St Mary’s Fort (near Peace River, Alta). On his way out in the summer of 1820 he was ambushed and re-arrested by the Nor’Westers at Grand Rapids (Man.) and taken to Lower Canada. He escaped at Hull, and went south into the United States.

From New York Robertson returned to England. But Selkirk, who had guaranteed his business, had died in April 1820 and he had to flee to France to avoid imprisonment for debt. By August 1821 he had settled with his creditors for two shillings on the pound, and was free but, as so often in his life, penniless. He returned to Lower Canada via the United States. Robertson was still a legal fugitive but, of greater consequence, from about 1819 he had lost the support of the London committee. As a result he was not directly involved in the negotiations that led to the union of the HBC and the NWC in 1821 [see Simon McGillivray]. Indeed, he had resisted the coalition, arguing that the HBC had been at the point of taking control in the Athabasca country. Still, there is little doubt that his determined assaults on the Athabasca between 1816 and 1820 were major factors in breaking down the opposition of the Nor’Westers to union.

Robertson was appointed a chief factor in the reorganized company in 1821 and was put in charge of Norway House (Man.). At this time he and Simpson – both of them energetic and audacious men – were in good accord. Although noting that as a “man of business he does not shine,” Simpson wrote in 1822 that Robertson “is a pleasant Gentlemanly Fellow and has none of those narrow constricted illiberal ideas which so much characterises the Gentry of Rupert’s Land.” But over the next decade Simpson developed the animus that is evident in his “Character book.” One can surmise that much of the reason for this change of attitude lay in the fact that the very characteristics which made Robertson invaluable as an aggressive leader in the conflict with the Nor’Westers made him seem bombastic and ineffectual in the routine work of the HBC after 1821, when, without rivals, it had no further need for men of dramatic action. Trade was now largely a matter of bargaining and accountancy, and Robertson had no flair for either.

He moved on from one post to another, mostly according to Simpson’s whims, and after 1821 received no promotion. In 1822 he was sent to Fort Edmonton (Edmonton), back to Norway House the following year, and in 1824 to Fort Churchill (Churchill, Man.). In 1825 he went to England to arrange the education of his eldest son, Colin. (He was a good husband and father, and treated his Métis wife with a consideration that coarser men, like Simpson, mocked.) On returning to North America he went to Fort Churchill until 1826, then to Island Lake and Oxford House, and in 1830 to Fort Pelly (Sask.).

In 1831 there was a major quarrel between Robertson and Simpson, whose racial prejudices were offended when Robertson brought his wife to Red River and tried to introduce her into what passed for society in that little settlement. Robertson now decided to retire, and made plans to sail for England and try to persuade the committee to let him retain his share as a wintering partner. But in 1832, before he could depart, he had what seems to have been a stroke, which paralysed his left side and from which he never completely recovered. For the next five years he was officially and unofficially on leave, not resuming work until 1837, when he was posted to New Brunswick House (on Brunswick Lake, Ont.).

Robertson retired officially in 1840, after the HBC had agreed to buy out his share. So extravagant had he remained in his style of living that the sale barely paid off the mortgage on his Montreal house. He was glad to accept a pension of £100 a year from the committee, though he spent many times that amount in borrowed money to get elected in 1841 as member of the Legislative Assembly for Deux-Montagnes. He did not live long to enjoy his political office. On 3 Feb. 1842 he was thrown from his sleigh, and the next day he died.

For a few years before 1821 Robertson had been an influential figure, helping materially to change the nature of the fur trade and the history of Canada, for no other individual did more to bring the NWC to an end. But after 1821 he became a cipher in the enlarged company he had helped to create. During the last decade of his life he was in obvious mental as well as physical decline, clinging in memory to his long-past feats as compensation for the frustrations of his later years.

GRO (Edinburgh), Perth, reg. of births and baptisms, 27 July 1783. PAC, MG 19, E1. PAM, HBCA, A.34/2; E.10; F.1–F.7. HBRS, 1 (Rich); 2 (Rich and Fleming). Papers relating to the Red River settlement . . . ([London, 1819?]). G. C. Davidson, The North West Company (Berkeley, Calif., 1918; repr. New York, 1967). J. M. Gray, Lord Selkirk of Red River (Toronto, 1963). Innis, Fur trade in Canada (1930). Morton, Hist. of Canadian west (Thomas; 1973). Rich, Hist. of HBC (1958–59), vol.2. M. [E.] Wilkins Campbell, The North West Company (Toronto, 1957).

Cite This Article

George Woodcock, “ROBERTSON, COLIN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 23, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/robertson_colin_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/robertson_colin_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | George Woodcock |

| Title of Article: | ROBERTSON, COLIN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | April 23, 2025 |