Source: Link

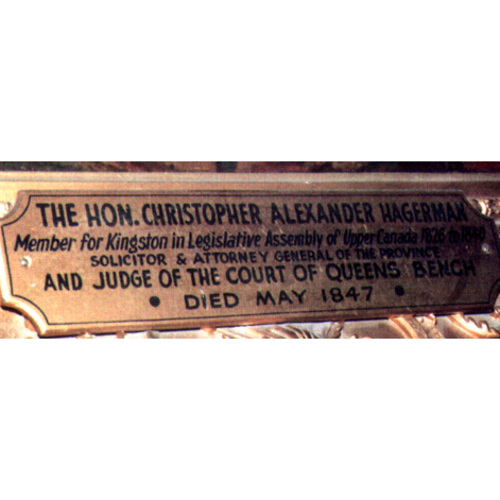

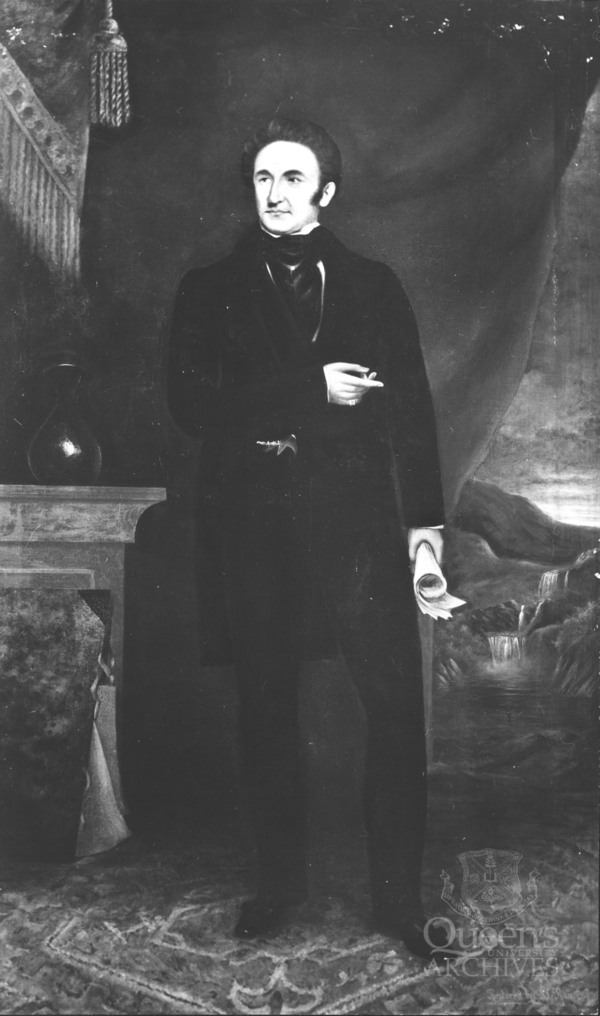

HAGERMAN, CHRISTOPHER ALEXANDER, militia officer, lawyer, office holder, politician, and judge; b. 28 March 1792 in Adolphustown Township, Upper Canada, son of Nicholas Hagerman and Anne Fisher; m. first 26 March 1817, in Kingston, Elizabeth Macaulay, daughter of James Macaulay*, and they had three daughters and one son; m. secondly 17 April 1834, in London, England, Elizabeth Emily Merry, and they had one daughter; m. thirdly 1846 Caroline Tysen, and they had no issue; d. 14 May 1847 in Toronto.

Few individuals in Upper Canada’s at times turbulent political history provoked such extreme hostility as Christopher Alexander Hagerman. Among the men with whom historians have commonly associated him, he was the most obdurate in his defence of church and state. He evinced – by temperament more than by design – the aggressiveness lacking in a John Macaulay* and outwardly less evident in a John Beverley Robinson*. William Lyon Mackenzie*’s biographer Charles Lindsey* thought Hagerman showed “a disposition to carry the abuse of privilege as far as the most despotic sovereign had ever carried the abuse of prerogative.” Charles Morrison Durand, a Hamilton lawyer prosecuted by Hagerman in the aftermath of the rebellion of 1837, depicted him as a “grim old bulldog.” If Macaulay was the back-room boy of Upper Canadian administrations from Sir Peregrine Maitland*’s to Sir George Arthur*’s, Hagerman was the bully-boy.

Unlike contemporaries such as Robinson, John Macaulay, Archibald McLean*, and Jonas Jones, all of whom moved easily, and naturally, into positions of influence and power, Hagerman started down life’s path as something of an outsider – lacking what Robinson termed “interest,” by which he meant a patron. It was not that Hagerman had no advantages; it was just that he did not have as many as others. His background was respectable and loyal. Nicholas Hagerman was a New Yorker of Dutch ancestry who “took an early and an Active part in favour of the British Government” during the American revolution. In 1783 he emigrated to Quebec, and the following year he settled on the Bay of Quinte in what became Adolphustown Township. He acquired a modest stature in the community as a militia captain and justice of the peace. More important professionally was his appointment in 1797 as one of Upper Canada’s first barristers

Within his closely knit family, young Christopher had an especial fondness for his brother Daniel and his sister Maria. From his father, it seems, he derived his keen sense of the loyalist legacy and an uncompromising adherence to the Church of England; it was perhaps symbolic that he had been baptized by John Langhorn*, one of the church’s staunchest defenders. A boyhood acquaintance, J. Neilson, recalled to Egerton Ryerson* in 1873 that Christopher had “not . . . much early learning,” and certainly, as historian Sydney Francis Wise has convincingly shown, he was never a pupil of John Strachan*. Hagerman embarked in 1807 upon a career in the law – one of the surest avenues to preferment and a comfortable life – as a student in his father’s Kingston office. He would be admitted to the bar in Hilary term 1815.

His personal qualities tended to set him apart. In November 1810, from York (Toronto), Robinson wrote to John Macaulay in Kingston: “We have been favored for two or three weeks with the company of the enlightened Christopher Hagerman a Youth whose bashfulness will never stand in his way – and who you may undertake to Say will never be prevented by embarrassments from displaying his natural talents or acquired information to the best advantage – After all, tho’, he has a good heart, and not a mean capacity, in short he is not So great a fool as people take him to be.” There was, as Robinson’s letter catches, a bravado and also an air of self-satisfaction to Hagerman, and they were as discernible in the young man as they would be characteristic of the older man.

His advance in society was effected through the good graces of outsiders, the military men who came to the province during the war years, stayed briefly, and cared little for local cliques. At the outbreak of the War of 1812 Hagerman enlisted as an officer in his father’s militia company. In 1833 he would write that he had “had the good fortune to attract the notice and obtain the patronage” of Governor Sir George Prevost*, who was in Kingston between May and September 1813. Hagerman’s rise in local and provincial society dates from that period. He carried dispatches for Major-General Francis de Rottenburg*, commander of the troops in Upper Canada, in August 1813. The following November he served with credit as Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Wanton Morrison*’s aide-de-camp at the battle of Crysler’s Farm. In December he was appointed provincial aide-de-camp to Lieutenant-General Gordon Drummond*, Rottenburg’s successor, with the provincial rank of lieutenant-colonel. It was a rather remarkable ascent.

More good fortune was yet to come. The office of collector of customs for Kingston had been vacant since the death in September 1813 of Joseph Forsyth*, and on 27 March 1814 Hagerman received the appointment. He was with Drummond during the May attack on Oswego, N.Y., and was acknowledged in Drummond’s official dispatch for having “rendered me every assistance.” Present at the siege of Fort Erie in September, he again carried dispatches the following month. Drummond’s high regard for his young aide was shared by his successor, Sir Frederick Philipse Robinson, who appointed Hagerman “His Majesty’s Council in and for the Province of Upper Canada” on 5 Sept. 1815. Hagerman had undoubtedly arrived in Upper Canadian society, but under the unusual circumstances of wartime. When normalcy returned with the reappearance of Lieutenant Governor Francis Gore*, absent since 1811, Hagerman’s appointment as counsel was undermined. Gore had wondered about it – in fact, he probably wondered who Hagerman was – and consulted the judges of the Court of King’s Bench. On 4 Nov. 1815 Chief Justice Thomas Scott* reported their unanimous opinion “that under all the circumstances of the intended appointment . . . it is not expedient for the present to carry it into effect.”

At the end of the war Hagerman resumed the practice of law in Kingston. His childhood friend Neilson, who observed him at the bar, remarked upon his “great powers of persuasion,” and these would bring him to the fore of his profession. He found, however, that the collectorship of customs occupied him more than he had anticipated. He had been obliged to rent a house for an office, “the expense of which is greatly disproportionate to the allowance and fees attached.” Accordingly, in 1816 he petitioned the Executive Council for the grant of a vacant lot in Kingston on which he could erect a house and office. He received one-fifth of an acre. He was already a landowner, having been granted in 1814 1,000 acres, which he located in Marmora Township, and another 200 as the son of a loyalist. As befitted a rising member of the bar, Hagerman involved himself in many community endeavours. Undoubtedly the “genial qualities” noted by Neilson made him an effective participant. Among the organizations to which he donated or subscribed by 1821 were the Midland District School Society, the Kingston Auxiliary Bible and Common Prayer Book Society, the Kingston Compassionate Society, the Lancasterian school, the Union Sunday School Society, the National School Society, the Society for Bettering the Condition of the Poor in the Midland District, and the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. He was a shareholder of the Kingston hospital, a trustee of the Midland District Grammar School, treasurer of the Midland Agricultural Society, and vice-president of the Frontenac Agricultural Society.

Most aspirants to a genteel life in Upper Canada required a wife of respectable family. Hagerman’s marriage in 1817 to Elizabeth Macaulay, whose brother George he knew well, was a fine match: her father was well connected, at both York and Kingston; her brother James Buchanan* would become an executive councillor in 1825. Hagerman himself was a good catch, securely positioned on the ladder of success. He had an affinity for women and an ease of manner which doubtless aided him in romantic endeavours; he was, as well, tall, rugged, and handsome. (Although in later life his looks were marred “by an accident to his nose which gave his face a peculiar appearance,” this “facial deformity,” John Ross Robertson* observed, was not “a bar to success in lovemaking.”) Few details emerge of his personal life, for there are no family papers. What glimpses remain are incidental, but they suggest that the geniality of the public man was as apparent in the private man. He seems to have been an affectionate father and a loving husband. His first daughter was born in 1820; writing to a friend a year later, he tacked on a playful after-thought to a postscript, “Our little brat is as usual.” He found amusing Chief Justice William Campbell*’s remark at an 1826 trial that “men as lords of the creation have a right to inflict a little gentle castigation on our rebellious dames.” The same year he fretted when his wife was stricken with a brief but “serious attack of illness.”

It was not long after his marriage that Hagerman became involved in politics. In 1828 he would declare that his chief political impulse had been “his anxiety . . . upon all occasions by supporting the views and measures of Government (emanating as he was well convinced they did from a source eminently disinterested and patriotic) to promote the best interests of the Province.” From the beginning he gave vent to that anxiety in a bruising fashion. In June 1818, in a minor way, he helped set the stage for the charge of seditious libel against the Scottish agitator Robert Gourlay*. Later that month he confronted Gourlay in the streets of Kingston brandishing a whip, which he used to good effect on the unarmed Scot. Arrested and subsequently released, he had given Kingstonians a visible demonstration of where he stood politically. A now prominent local, Hagerman was elected to the House of Assembly for the riding of Kingston on 26 and 27 June 1820. He defeated, by 119 votes to 94, George Herchmer Markland*, a pupil of Strachan’s, a friend of Robinson and John Macaulay, and the son of leading Kingstonian Thomas Markland.

Hagerman entered the eighth parliament (1821–24) with a reputation outside Kingston at odds with his beliefs. A surprised Robinson at York admitted to Macaulay in February 1821 that he had been “grievously mistaken” about Hagerman: “He is any thing but a Democrat. Indeed his conduct is manly, correct & sensible & shews in every thing that kind of independence most rarely met with which determines him to follow the right side of a question tho’ it may appear unpopular – his speeches gain him great credit.” Such a misapprehension by Robinson, who had known Hagerman since 1810, worked with him (albeit briefly) during the war, and cooperated with him in the charge against Gourlay, may reflect a more widespread confusion about political stances. Mackenzie, after all, initially believed Jonas Jones to be a member of the opposition in the same parliament. Whatever the nature of the misunderstanding, it was quickly rectified. By mid February Hagerman and Robinson were working together and taking the lead on administration measures. The end of session won Hagerman strong praise from the attorney general, who wrote to John Macaulay: “Our friend Hagerman is a sterling good fellow, free from prejudices, and with every bias on the right side. . . . His talents & information can not well be spared.”

In his political views Hagerman was “illiberal,” to use the word Robinson would attach to himself in 1828 (the word “conservative” had not yet entered the political lexicon of Upper Canadians). He was also, to adopt another of Robinson’s phrases, a “wellwisher of Church & State.” In 1821 he supported William Warren Baldwin’s defence of aristocracy and primogeniture against an intestate estate bill sponsored by Barnabas Bidwell* and David McGregor Rogers*. To vote for the measure would, Hagerman argued, “be departing from every thing venerable, noble, and honorable; . . . Democracy was, like a serpent, twisting round us by degrees, it should be crushed in the first instance, for if the bill passed, it would not leave them the British Constitution but a mere shadow.” For Hagerman, the essence of the constitution was monarchy and executive prerogative. That same year he opposed a bill repealing the civil list since “it was necessary that the Executive government should have a fund of this description at their disposal; it is the case in all governments except those that are purely democratical. . . . Monarchy should be supported, and if you infringe a hair’s breadth, you endanger the whole fabric.” He was also a leading participant in the debate over Barnabas and Marshall Spring* Bidwell’s eligibility to sit as members, the opening shot in the war known as the alien question.

At another level, Hagerman proved a good constituency man, working on and proposing a number of measures of local concern. His major role in this regard was to second John Macaulay’s leadership of Kingston’s pro-union forces when the question of a union with Lower Canada arose in 1822. The separation of the old province of Quebec in 1791, he maintained, had “most unnaturally rent asunder . . . subjects of the same great and glorious empire, whose interests nature has made inseparable, and whose strength and improvement depends solely and entirely on their being united by concurrence of habits and sentiments, and a right understanding of their common interest.” Macaulay argued the case for union on financial and economic grounds; Hagerman agreed with his views but concentrated on political and constitutional matters, which were the leading concerns of anti-unionists such as Baldwin. Hagerman, an ardent defender of the Constitutional Act of 1791, which had given Upper Canada its constitution, was as concerned as Baldwin not to jeopardize any of its essential parts. He favoured union as a means of overwhelming at an early stage Lower Canadian oppositionists whose advocacy of the assembly’s powers at the expense of the Legislative Council’s threatened “that balance between absolute monarchy and democracy, which so beautifully distinguished the British Constitution.” What happened in the lower province would affect Upper Canada sooner or later, Hagerman argued. Thus, Upper Canadians should shun the role of “indifferent observers” or risk “losing the constitution under which they live.” Though popular with Kingston’s mercantile community, Hagerman’s advocacy of union was insufficient to guarantee his re-election in 1824.

In fact, in a two-way race – a third candidate, Thomas Dalton, a local brewer and banker, withdrew – Hagerman was defeated, polling a mere 11 votes short of his opponent’s total. Dalton took credit for Hagerman’s loss, but the explanation is more complex. As S. F. Wise has argued, Hagerman may have been hurt by his injudicious remarks in the dispute over the “pretended” Bank of Upper Canada at Kingston. Hagerman had been an early director and shareholder, as was Dalton; at the time of the bank’s collapse in 1822 he was its solicitor and shortly thereafter he became chairman of the board of directors to oversee its dissolution. In March 1823 parliament declared the bank illegal, made the directors liable for its debts, and set up a commission consisting of John Macaulay, George Markland, and John Kirby to handle the institution’s affairs. The commissioners’ report, tabled the following year, was unfavourable to the bank’s administrators. Hagerman attacked the report, defending the directors with the exception of Dalton. Dalton responded with a masterpiece of vitriol condemning as spurious Hagerman’s criticism of the commissioners and accusing him of being in league with them to destroy his reputation. Since as early as January 1823 Hagerman’s own reputation had been undermined by “reports and insinuations” that his conduct as chairman was not in the best interests of the bank, Dalton’s squib identifying him with the agents of the York élite may well have raised the ire of those who suffered by the bank’s failure and thus influenced the outcome of the election.

Hagerman’s defeat may also have had to do with his bumptious manner, which carried over into every aspect of his career. At a social gathering in York on 30 Dec. 1823 Hagerman, in the presence of Lieutenant Governor Maitland, Chief Justice William Dummer Powell*, and Mr Justice William Campbell, insinuated, as Campbell related the incident to Maitland’s secretary, Major George Hillier, that judges were “in the habit of deciding otherwise than according to the laws we are appointed to administer.” An annoyed Campbell was left with the option of passing over the incident “in silence as an instance of rudeness and ill manners unworthy of serious notice, or of adopting such measures as I may conceive best adapted to the support of my judicial character, and to the proper notice of personal insult.” Early that year Hillier had been “very much distressed” by a report of a “flagrant breach of decorum” on Hagerman’s part towards Robert Barrie, commissioner of the Kingston dockyard. Strachan informed Macaulay of the “many rumours” surrounding this affair and of Hagerman’s “recent argument” with Thomas Markland. Yet there was more. Strachan had been told that Hagerman wished to be solicitor for the bank commissioners who were investigating the bank of which he was already the solicitor – “an indelicacy,” Strachan sighed, “which I would have considered incredible.”

If Hagerman could give offence, with such apparent ease, to men of his own rank and station, he could prove unbearable to others. As collector, he enforced customs regulations with exactitude. He had, for instance, invaded Carleton Island, N.Y., in 1821 to seize a depot of tea and tobacco kept there by Anthony Manahan, whom he dismissed as a smuggler and a “Yankee Merchant.” He even suggested to Hillier that he should be allowed occasional recourse to a military force to assist him. Early in July 1824 one Elijah Lyons was accidentally shot by a student in Hagerman’s law office who was aiding him in this instance in his customs duties. Two months later 31 Kingstonians complained to Maitland of Hagerman’s “proceedings and conduct.” When “in the hands of a passionate, vindictive, ambitious, or speculating person” the enormous powers of the collectorship were, the petitioners wailed, “dangerous to the rights and property of individuals, the usual course of business, and the public peace.”

Having been forced out of political life temporarily, Hagerman returned to his legal practice and his various endeavours. He bought, sold, and let properties throughout the Midland District and beyond it. He served as an agent for a number of proprietors and sometimes acquired lots in partnership with others. He was vice-president of the Kingston Savings Bank in 1822 and a director of the Cataraqui Bridge Company four years later. The failure of the “pretended” bank had cost him dearly, £1,200 plus contingencies by his reckoning, and by 1825 he had “to save money.” He declined the offer of a District Court judgeship in October of that year because “I cannot afford to give up any portion of my practice in the Kings Bench, which I have reason to think wd. be materially affected by discontinuing my acceptance of suits in the inferior court.” He was, however, willing to take an out-of-district judgeship and on 14 June 1826 Hillier notified him of his appointment to the Johnstown District.

Hagerman was a skilled lawyer who had, with Bartholomew Crannell Beardsley*, defended John Norton* of the charge of murder in 1823. He won further notoriety for himself in the fall of 1826 by defending the young bucks who had destroyed Mackenzie’s printing-office and press. Although his law office was “lucrative” in the 1820s, Hagerman was tiring of it, and his professional weariness coincided with his reservations about town life. In 1827 he purchased a country property, living with his family in a “small, but comfortable stone cottage” until a “more spacious Mansion” was completed. He had “no intention” of returning to Kingston: “I have been living long enough in a style of expense, agreeable (to be sure) to my own taste, but which with reference to the claims of my little ones, it is not prudent I should continue.”

In that year he was looking for advancement. He sought, he told Hillier, “preferment in my profession” but not “in any other department.” He hoped that if an opportunity arose “during the present administration” he would not be disappointed. Early the next year he memorialized Maitland for elevation to the Court of King’s Bench – Campbell was in England seeking a pension on which to retire and judge D’Arcy Boulton* was ailing and close to retirement. At that time the administration of justice was swirling in a storm of controversy [see William Warren Baldwin], the result of William Forsyth’s petition to the assembly in January 1828 complaining of Maitland’s high-handed treatment of him. The political skies darkened further with the dismissal of Mr Justice John Walpole Willis* in June 1828 and no doubt became even more threatening with Hagerman’s unexpected nomination to the bench as Willis’s successor that same month. Hagerman was simply too much the partisan for his appointment to restore to the Maitland administration any of the goodwill it had lost on such issues as political reform, the clergy reserves, the administration of justice, and the alien question. There was one boon for the opposition in Hagerman’s nomination: he was unable to contest the general election held that summer.

Having been allowed sufficient time to wind up his affairs in Kingston and move to York to take up his unconfirmed appointment, Hagerman went on circuit in August 1828. He reported to Hillier from Brockville that “I have so far had no very unpleasant duty to perform, nothing has occurred worthy of particular note.” Matters quickly changed when, in Hamilton on 5 September, he presided at the trial of Michael Vincent, charged with murdering his wife. Casting aside the tradition that a judge should serve as the accused’s counsel, not his prosecutor, Hagerman advised the petit jury that “the deceased had been murdered by the prisoner; and he had no difficulty in saying such was his opinion.” Over the objections of John Rolph*, who was acting for the defence, the jury retired and found Vincent guilty. Hagerman sentenced him to execution and dissection, and three days later he was hanged in a badly botched manner. Bartemas Ferguson*, editor of the Niagara Herald, found Hagerman’s charge “remarkable” and wondered whether it had given “an undue bias to the jury.” Francis Collins* of the Canadian Freeman saw in Hagerman’s action an extraordinary departure, yet another instance of irregularity in the administration of justice. In his view Hagerman was an incompetent whose only qualification for the bench was sycophancy. Although the feeling was by no means universal, it was shared by many among the administration’s opponents. After the ninth parliament opened in January 1829, Hagerman was, as Robert Stanton* observed, “every day called Judge Kit and has every odious invective brought against him.” By July rumours abounded that his appointment would not be confirmed. They proved true. Robinson replaced Campbell on the bench and James Buchanan Macaulay replaced Hagerman. The new lieutenant governor, Sir John Colborne*, reported to the colonial secretary that Hagerman thought himself “ill used.”

But there were compensations. Since his arrival in August 1828 Colborne had shunned Maitland’s key advisers, Robinson and Strachan, and Hagerman stepped alone into the limelight of gubernatorial favour, becoming for a time the conduit for privileged information. To make up for the loss of his judgeship he was appointed solicitor general on 13 July 1829. His prestige was enhanced the following year by his election victory over Donald Bethune* in Kingston. He was re-elected in 1834, handily beating William John O’Grady. By this time Kingston had become Hagerman’s private bastion; he was elected by acclamation in 1836.

With Robinson on the bench government management of the assembly in the eleventh parliament (1831–34) fell to Hagerman and Attorney General Henry John Boulton* – with disastrous results. The latter was an inept dandy, the former was unequal to the task. Hagerman’s strength was his dogged commitment to the administration and to his own principles of church and state. His talent was a natural eloquence invigorated by the passion of the moment. The Kingston Chronicle caught him in full swing during an 1826 trial, and the editor’s conclusion was apt: “We have heard those who could, perhaps, reason more closely than Mr. Hagerman but very few indeed whose eloquence . . . is more powerful.” He was, as Thomas David Morrison* would characterize him in 1836, “the Thunderer of Kingston,” a man given to “violent expressions of opinion.” Yet in debate, discourse, or conversation, once excited or engaged, Hagerman usually did more harm than good to the causes he so forcefully espoused. The most glaring example was his role, with Boulton, in the repeated expulsions of William Lyon Mackenzie from the assembly. When word of their actions reached Lord Goderich, the colonial secretary, both law officers were dismissed in March 1833. Colborne protested, however, and Hagerman, now a widower, set off for England to appeal. He returned the following year with a reinstatement from the new colonial secretary, Lord Stanley.

He also returned with a new wife. According to George Markland, “The match was not approved of in a certain quarter of the country – they said openly that nothing had ever occurred which caused so much annoyance – The Miss Merry and Kit Hagerman oh it was horrible they said.” Perhaps it was her attractions that made politics and his official duties irksome to Hagerman. Or perhaps it was a desire for change such as had overtaken him in the mid 1820s. Whatever it was, Robert Stanton noted in 1835 Hagerman’s inability to put his imprint on the twelfth parliament and his more frequent absences from the house. He was, however, there, and on the defensive, in 1835 when he unsuccessfully opposed M. S. Bidwell’s election as speaker, and when the house reduced his salary as solicitor general from £600 to £375.

That year, moreover, he was embroiled in a defence of the Church of England and the clergy reserves following upon Colborne’s endowment of 44 Anglican rectories in December, a political error of enormous proportions. For Hagerman, a self-declared “High Church & King’s man” who had equated dissent with “infidelity,” the established church was a key bulwark against immorality, equality, and a godless democracy. He was a devout member of his own congregation, St George’s in Kingston, and in 1825 had been a member, with John Macaulay and Stanton, of a committee that wrote an arrogant defence of the Anglicans’ exclusive jurisdiction over the town’s lower burial-ground. When John Barclay* penned a claim for the equal rights of the Church of Scotland, Hagerman, as Robinson revealed, was one of the three anonymous authors who replied. In 1821 he had naturally assumed a direct connection between Robert Nichol*’s remark in the assembly that there was no established church in Upper Canada and the desecration of the Anglican church in York later in the evening. Given his convictions, it is not surprising to find him leaping to Colborne’s defence in the matter of the Anglican rectories. The lieutenant governor’s blunder was, however, only compounded by Hagerman’s thoughtless affronts to virtually every other denomination.

Hagerman’s efforts in 1836 to stem the political fury aroused in the assembly by Lieutenant Governor Francis Bond Head*’s confrontation with the Executive Council [see Robert Baldwin*; Peter Perry*] were futile. He made up his mind “to retire into private life.” His parliamentary and official duties kept him from his private office “longer than is convenient, to say nothing of the great draw back upon my domestic comfort.” There had been rumours in October 1834 of his possible re-elevation to the bench. Change did come but it was not what he wanted. On 22 March 1837 he succeeded Robert Sympson Jameson* as attorney general; Hagerman’s law partner since 1835, William Henry Draper*, took over the solicitor generalship. Colonial Secretary Lord Glenelg, however, refused to approve Hagerman’s appointment. He had no reservations about Hagerman’s “private character and public merit” but professed grave doubts about the compatibility of his religious opinions with those of the government. At issue were Hagerman’s denigrating remarks about the Church of Scotland in the assembly on 9 February. The congregation of St Andrew’s Church in Kingston (Barclay’s old church) had forwarded to the Colonial Office a resolution condemning Hagerman’s “grossly incorrect statements and intemperate language.” Head explained to Glenelg in September that Hagerman’s speech had been “purposely and mischievously made as offensive as possible to the Scotch” by Mackenzie in his newspaper. Combined with Hagerman’s personal assurances as to what had been said, Head’s defence persuaded Glenelg to order Hagerman’s warrant in November.

The outbreak of rebellion in December 1837 (Hagerman had noted on 30 November “the general quiet and contentment that prevails”) brought – or necessitated – renewed commitment to public life. He was preoccupied through 1838 and 1839 with administrative details and judicial questions relating to the handling of rebels and Patriots. Although he was the father-in-law of Head’s secretary, John Joseph*, the connection availed him little more than ready access to the lieutenant governor. Robinson was Head’s key adviser, and two recent recruits to the administration, John Macaulay and Robert Baldwin Sullivan*, were the rising stars. Hagerman could not match their abilities in administrative work, analysis, or policy. Head’s terse notations about the men on his executive capture Hagerman perfectly: “Able speaker loyal constitutionalist but I have no very high opinion of his judgement. Sound, honest.” Neither Hagerman’s standing as a courtier nor the cast of characters in government changed greatly when Sir George Arthur succeeded Head in March 1838. Arthur considered him “an honest straight forward Person – Sees matters rightly, and will speak with energy – but, then, He is not a hard Worker!” Arthur was aghast at Hagerman’s reaction to the arrival of the report of Lord Durham [Lambton]: “He read the Report, and then went out to a party to Dinner! – Whereas He should have sent an excuse, & at once have set down & commented upon it, & without loss of time brought it under the notice of the House.”

The question of a union of Upper and Lower Canada had been a topic of growing concern through the second half of the 1830s and Hagerman’s stand is of interest. In February 1838 he indicated in debate that he would support union only if there were sufficient safeguards to ensure English-Protestant supremacy. Confronted by the union bill of 1839 he damned it as “republican in its tendency” and urged strengthening the “Monarchical principle.” But when the bill came to a vote in the assembly on 19 Dec. 1839, Hagerman, brave declarations of opposition to the contrary, supported the union. The swaggering attorney general had in fact wilted under pressure from Governor Charles Edward Poulett Thomson. On 24 November Thomson, in private conversation with Arthur and John Macaulay, had wondered why “officers appeared to act as if they regarded not the will of the Government in any matter of public policy.” The governor’s first impulse was to dismiss his recalcitrant law officer but he decided against it on the advice of Arthur. After a frank discussion with Thomson on 7 December, Hagerman emerged with his bold opposition to union intact. Five days later he declared in the assembly that administrators could not be coerced into supporting it. He was, however, crumbling rapidly. In the assembly on the 19th he explained that since the union resolutions were before the house “by command of the Sovereign,” “if the vote in favour . . . was persisted in, he would vote for them.” John Macaulay informed a correspondent that he was disturbed to “see Hagerman’s friends set up a comparison between his conduct & mine upon the Union Question – I would be sorry to set up so high as he did & after all break down.” “You will soon hear,” he added, “that he has retired . . . to a Puisne Judgeship.” And indeed, with Levius Peters Sherwood’s retirement, Hagerman joined Robinson, J. B. Macaulay, MacLean, and Jones on the bench, the appointment taking place on 15 Feb. 1840. His former partner Draper succeeded him as attorney general.

Upon his elevation Hagerman turned over his law practice to James McGill Strachan*. He had hoped for an immediate leave but was obliged to wait until late August 1840 before sailing to England with his wife; they returned in July 1841. Compared to the demands of his previous life, the routines of the court must have seemed somewhat dull. Between March 1840 and October 1846 he travelled the circuit to various assizes on ten occasions, holding court almost 50 times. He also had the regular sittings of Queen’s Bench en banc. His career as a judge awaits further study but one possible contribution should be noted. On 15 April 1840 he presided at the trial in Sandwich (Windsor) of Jacob Briggs, a black man charged with the rape of an eight-year-old white girl. The legal definition of rape required proof of both penetration and emission, and Hagerman so instructed the jury. Despite contradictory evidence – medical testimony for the defence held “it would have been impossible for a full grown man, particularly a Negro to have entered the body” of a young girl – the jury found Briggs guilty, and Hagerman sentenced him to execution. Reporting on the case to the Executive Council, Hagerman overlooked the necessity of proving emission and concentrated on the question of penetration, coming to the conclusion, “most consistent with Law and reason,” that to convict for rape it was not necessary to prove that the hymen had been ruptured. After consulting with his colleague J. B. Macaulay, Hagerman decided that there was no legal objection to the jury’s verdict. The councillors agreed but commuted the sentence to transportation. The following year the statute on rape was revised and the technicality with respect to emission abandoned, a move hailed by feminist historians as a major turning-point in the law. Although evidence of a direct connection between Hagerman’s report and the 1841 law is lacking, it seems reasonable to conclude that it had some impact upon law officers as indicating the views of the judiciary.

Political power was gone for Hagerman in the 1840s. Chastened by his brush with Thomson, he had assured Arthur in August 1840 of his resolve “not to mix myself with party strife or discussion in any way.” The following year, from London, Arthur reported to Thomson, now Lord Sydenham, that he had seen Hagerman at a party and that he “talked a great deal as he always does but he was subdued in all his remarks.” In 1842, however, Hagerman did not hesitate to urge John Solomon Cartwright “on no account whatever to associate yourself in the Govt with abettors of treason – or the apologists of traitors.”

In his private life Hagerman was shaken by the death of his second wife in 1842, but his grief was allayed by his faith in the providential origins of all change. In 1823 he had offered his sympathy to John Macaulay on the death of a younger brother. “We cannot,” he wrote, “expect to pass through this life without afflictions, and when Providence dispenses them we may be benefited by reflecting that by being good and virtuous we shall avert the remorse which attaches to those who are compelled to regard them as the punishments due to vice.” He himself had been fortified by his convictions over the course of many family bereavements. Of his daughter Anne Elizabeth Joseph’s death in 1838, he notified an acquaintance that “it has pleased God to take this Child from me.”

Hagerman was married for a third time in 1846 Caroline Tysen was an English lady like his second wife. That year he was planning to retire to England when he took ill. His will, signed in a barely legible scrawl and noteworthy for the omission of any mention of religion, stipulated various bequests, the most important of which went to his two surviving daughters. He made provision for his son Frank, presumably a feckless youth who had been a disappointment to him, with the caveat that the executors pay the yearly amount only if they “shall consider that it is right and proper . . . having a due regard to the manner in which he shall conduct himself.” On 18 March 1847 Larratt William Violett Smith, a young lawyer, wrote: “Poor Judge Hagerman is still lingering on, so reduced that he may be said to be dying. His worthless son staggers drunk to his bedside in the daytime, whilst his nights are spent in the most abandoned company.” Hagerman died two months later; shortly afterwards his wife returned to England.

Hagerman had been useful to successive administrators from Maitland to Arthur. He enjoyed his greatest intimacy with Colborne, who would, however, in time seek out Robinson as a confidant. Hagerman was, perhaps, especially in the late 1830s, a convenient symbol of the uncompromising courtier in what was then known as the “family compact” – certainly Francis Hincks*’s Examiner portrayed him as such – but he lacked the talents and intellect which made Robinson, Strachan, Macaulay, and Jones more important. His forte was sound and fury and more often than not it got him into trouble.

Christopher Alexander Hagerman is the author of Letter of Mr. Attorney General to the editor on the subject of Mr. Bidwell’s departure from this province . . . (Toronto, 1838). A speech he delivered in the assembly was published in Speeches of Dr. John Rolph, and Christop’r A. Hagerman, esq., his majesty’s solicitor general, on the bill for appropriating the proceeds of the clergy reserves to the purposes of general education . . . (Toronto, 1837). His “Journal of events in the War of 1812” for 1813–14 is held at the MTRL.

AO, MS 4; MS 35; MS 78; MS 186 (mfm.); MU 1376; MU 1838, no.537; MU 2319; MU 2818; RG 22, ser.155; ser.159, Nicholas Hagerman, Daniel Hagerman. Law Soc. of U.C. (Toronto), Minutes. MTRL, William Allan papers. PAC, MG 24, A40; RG 1, E3; L3; RG 5, A1; RG 7, G1. PRO, CO 42. Arthur papers (Sanderson). [Thomas Dalton], “By the words of thy own mouth will I condemn thee”; to Christopher Alexander Hagerman, esq. ([Kingston, Ont.?, 1824]; copy at MTRL). Doc. hist. of campaign upon Niagara frontier (Cruikshank), vols.1–2, 6, 8–9. Charles Durand, Reminiscences of Charles Durand of Toronto, barrister (Toronto, 1897). [Charles Grant, 1st Baron] Glenelg, Lord Glenelg’s despatches to Sir F. B. Head, bart., during his administration of the government of Upper Canada . . . (London, 1839). F. B. Head, A narrative, with notes by William Lyon Mackenzie, ed. and intro. S. F. Wise (Toronto and Montreal, 1969). “Journals of Legislative Assembly of U.C.,” AO Report, 1914. Select British docs. of War of 1812 (Wood). “A register of baptisms for the township of Fredericksburgh . . . ,” comp. John Langhorn, OH, 1 (1899): 34, 38. [L. W. V.] Smith, Young Mr Smith in Upper Canada, ed. M. L. Smith (Toronto, 1980). U.C., House of Assembly, Journal, 1832–40. British Colonist, 1838–39. Canadian Freeman, 1828. Chronicle & Gazette, 1833–45. Examiner (Toronto), 1838–40. Kingston Chronicle, 1819–33. Kingston Gazette, 1815. Niagara Herald (Niagara [Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont.]), 1828. Patriot (Toronto), 1835–36. Royal Standard (Toronto), 1836–37. U.E. Loyalist, 1826. Weekly Register, 1823. York Weekly Post, 1821. Death notices of Ont. (Reid). DHB (biog. of Michael Vincent). Reid, Loyalists in Ont. C. B. Backhouse, “Nineteenth-century Canadian rape law, 1800–92,” Essays in the history of Canadian law, ed. D. H. Flaherty (2v., Toronto, 1981–83), 2: 200–47. D. R. Beer, Sir Allan Napier MacNab (Hamilton, Ont., 1984). William Canniff, History of the settlement of Upper Canada (Ontario), with special reference to the Bay Quinte (Toronto, 1869; repr. Belleville, Ont., 1971). Darroch Milani, Robert Gourlay, gadfly. R. L. Fraser, “Like Eden in her summer dress: gentry, economy, and society: Upper Canada, 1812–1840” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1979). W. S. Herrington, History of the county of Lennox and Addington (Toronto, 1913; repr. Belleville, 1972). Lindsey, Life and times of Mackenzie. Robertson’s landmarks of Toronto, 1: 274. S. F. Wise, “The rise of Christopher Hagerman,” Historic Kingston, no.14 (1966): 12–23; “Tory factionalism: Kingston elections and Upper Canadian politics, 1820–1836,” OH, 57 (1965): 205–25.

Cite This Article

Robert L. Fraser, “HAGERMAN, CHRISTOPHER ALEXANDER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 25, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hagerman_christopher_alexander_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hagerman_christopher_alexander_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert L. Fraser |

| Title of Article: | HAGERMAN, CHRISTOPHER ALEXANDER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1988 |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | November 25, 2024 |