Source: Link

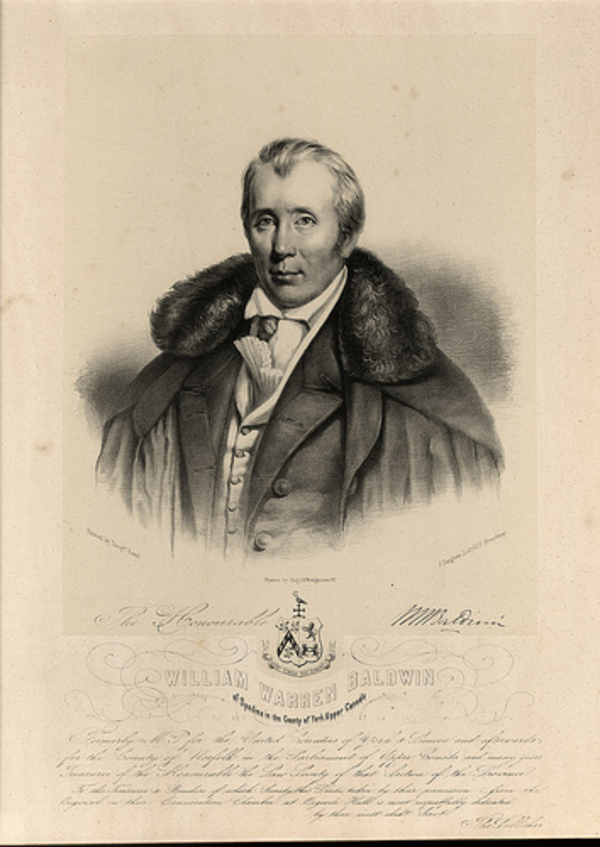

BALDWIN, WILLIAM WARREN, doctor, militia officer, jp, lawyer, office holder, judge, businessman, and politician; b. 25 April 1775 at Knockmore, the family estate south of Cork (Republic of Ireland), fifth of the 16 children of Robert Baldwin and Barbara Spread; m. 26 July 1803 Margaret Phœbe Willcocks, daughter of William Willcocks*, in York (Toronto), and they had five sons, including Robert*; d. 8 Jan. 1844 in Toronto.

Robert Baldwin Sr was a Protestant gentleman farmer who had, by the time of William Warren Baldwin’s birth, acquired both office and prestige. For a time in the 1780s he published, with his brother, the Volunteer Journal; or, Independent Gazetteer, which William Warren later claimed had been “favorably spoken of” by Charles James Fox. In spite of continuous attention to his estates during his political involvement with the volunteer movement and despite the financial support of his patron, Sir Robert Warren, Robert slid into bankruptcy about 1788. None the less, young William received a proper education. In his will he was to leave a small sum to an heir of the Reverend Thomas Cooke, “my careful and good schoolmaster, whose attention and kindness to me demands this small acknowledgement.” About 1794 he entered medical school at the University of Edinburgh, from which he graduated in 1797.

That same year, enticed by descriptions sent back by a former neighbour, Robert Baldwin resolved, contrary to his patron’s advice, to emigrate to Upper Canada. He sailed in 1798 with William, one other son, and four daughters. Forced to winter in England, the family set forth again the following spring. Although family accounts give 13 July 1799 as the date of their arrival at York, Robert’s first petition for land is dated 6 July. In it he expressed his desire for a grant, having heard “of the fertility of the soil & the mildness & good Government” of the province. There was, however, more to his emigration: Baldwin had been, according to the reminiscences of his youngest daughter, deeply alarmed by the persistent rumours of impending French landings in Ireland, in anticipation of which he had barricaded his house and armed his servants. The unrest preceding the uprising of the Society of United Irishmen in 1798 had also played a part in convincing him of the need to leave. William noted in 1801 that the “horrors of domestic war [had] conspired to drive us from our native country.”

Robert’s entry into Upper Canadian society had been well prepared. On 20 Aug. 1798 his friend Hugh Hovell Farmar wrote a letter introducing him to President Peter Russell*, another Irishman, which described him as a “Gentleman of excellent Family, of Honor & excessively clever in the farming Line, with great Industry.” For his part, Russell strongly recommended Baldwin’s petition to the Executive Council and he received 1,200 acres. He settled, however, on land he had purchased near an acquaintance in Clarke Township. With excellent connections, he soon acquired offices, among them the lieutenantcy of Durham County, and influence.

William found his new life in the Upper Canadian wilds unprepossessing. There, he wrote to his brother in 1801, he was “banished from all that is engaging in life, flattering to our hopes, or grateful to our industry.” Although his father’s appointments from Lieutenant Governor Peter Hunter* were “all honour but not profit,” he found them “agreeable,” assisting “in some measure to soothe the mind.” He himself was appointed lieutenant-colonel of the Durham militia, a group he considered “a lawless . . . damned set of villains”; he also became a justice of the peace on 1 Feb. 1800. William was concerned about unrest in the province, which he attributed to “unprincipled wretches” from the United States who “would, had they the least prospect of success, tomorrow attempt to overturn the order of things in this country.”

Finding little scope for his professional ambition in the backwoods of Clarke and preferring the allures of York’s small society, Baldwin moved in 1802 to the capital, where he entered the somewhat closed family world of the Russell and Willcocks households. His connections to them were established in Upper Canada but the ties went back to Cork and Hugh Farmar, who was “nearly allied” to both families. Peter Russell’s “friendship” was of particular consolation to Baldwin, and Peter was a first cousin of William Willcocks, soon to be Baldwin’s father-in-law. Another close friend was Joseph Willcocks*, a distant relation of William. In June 1802 Baldwin acted as Russell’s intermediary with Joseph Willcocks, whose advances to Elizabeth Russell* had caused a breach in their relations. But even York offered little scope for an aspiring young doctor and in December he advertised the opening of a classical school for young gentlemen. What became of it is not known. Baldwin’s career now took a new direction. The young man who had borrowed Sir William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the laws of England from Russell became an attorney on 22 Jan. 1803 and was admitted to the bar in Easter term of the same year.

Baldwin was a visible member of York’s social circle and was one of the town’s most eligible bachelors, a state ended by his marriage to Phœbe Willcocks in 1803. The young couple lived briefly with the Willcockses until they moved into their own home shortly before the birth of their first child, Robert, in May 1804. In spite of the death of their second son in 1806 and the frailness of the third, William Willcocks reported in 1807 that his daughter was “happily Married.” With the birth of sons in 1808 and in 1810, Baldwin’s family would be complete. He was a doting father, often glimpsed in the diaries of early York making his rounds of the town with one or more children in tow.

The society of York was a cliquish world in which competition for the few profitable offices was fierce. Conventional wisdom attributes William Warren Baldwin’s rise to Russell, but he was in fact in eclipse when the Baldwins arrived and they garnered most of their early rewards from Hunter. In 1806, while the vultures of official York were awaiting the fall of James Clark*, clerk of the Legislative Council, Russell was unsuccessful in persuading President Alexander Grant* that Baldwin should succeed him. For several weeks early in 1806 Baldwin had served as acting clerk of the crown and pleas. In spite of judge Robert Thorpe’s recommendation that he was “the only educated and qualified person in the Province” for this position, it went to John Small*. None the less, Baldwin picked up his share of plums. On 5 Feb. 1806 he followed David Burns as master in chancery, on 19 Nov. 1808 he became registrar of the Court of Probate, and on 22 July 1809 he was appointed a district court judge.

During Lieutenant Governor Francis Gore*’s first administration (1806–11), many of Baldwin’s friends – Joseph Willcocks, William Firth, Thorpe, and Charles Burton Wyatt – were either suspended or dismissed from office. Despite Baldwin’s association with them and despite Gore’s suspicion of him as an “Irishman, ready to join any party to make confusion,” he survived. His political legerdemain was remarkable and deliberate: although it was clear who his friends were – and although he supported Thorpe during his trial for libel in 1807 – he avoided any overt demonstrations of his political sympathies. Indeed, in October 1809 he wrote to Wyatt of Gore’s “disposition to befriend” him. But if William did well during this period, as his appointments to office in 1808 and 1809 evidence, others were doing better. Baldwin was not the only able and ambitious lawyer in town and he resented, although he professed not to, the meteoric ascent of John Macdonell* (Greenfield). When Greenfield made some “wanton & ungentlemanly” references about him in court, Baldwin demanded an apology and ultimately challenged him to a duel. In a note he enjoined his wife, whom he had described in a hastily made will as “unparalleled in all the excellent qualifications of her sex,” “not to indulge a rash or resentful spirit, but to protect me from insults, which as a gentleman I cannot submit to.” On 3 April 1812 the two men met on Toronto Island. Macdonell did not raise his pistol, which Baldwin interpreted “as an acknowledgement of his error – we joined hands thus this affair ended.”

Baldwin gloried in domesticity. By the end of the War of 1812 his household included his wife, four sons, father, three sisters, sister-in-law, Elizabeth Russell, and a few servants. The extended family, usually with more relations living in close proximity, became a pattern found in several generations of Baldwins. William believed that “nature has placed the Father in the situation of absolute Governor in his own House.” The centre of the household was Phœbe, whom her son Robert later described as “the master mind of our family.” A sister of William’s extolled Phœbe’s “excellent understanding and mental attainments,” which “were of the greatest consequence and assistance to him.” Phœbe herself caught what marriage meant to the Baldwin men in a letter to Laurent Quetton* St George in 1815: “No real domestic comfort is to be enjoyed without a good Wife.” She rarely emerges from the shadows (few letters from her have survived) but what gleanings there are point to a dominant figure. William himself was an urbane, polished gentleman, tough-minded and possessed of a high self-regard. Yet he harboured a vulnerability which, if trifling in comparison to his son Robert’s, was more real than has often been supposed. Elizabeth Russell described him in her diary as “a poor dead hearted creature and always fears the worst.” Phœbe’s illness in the fall of 1809 occasioned “a gloomy mood”; as he later explained to St George, “I am an Irishman and my wife was ill.” To be sure, in such a large extended family illness and death were frequent. Peter Russell died in 1808 and William Willcocks in 1813. Robert Sr, a man subject to “low spirits,” died in November 1816. William himself suffered “an attack which . . . nearly carried me off” in the spring of 1817 and he was a long time recuperating. About this time his sister Alice (Ally) slipped into a sometimes violent and “unhappy insanity.” After two suicide attempts, she was sent in 1819 to the Hôpital Général of Quebec (where she remained until her death in 1832). Elizabeth Russell’s death in 1822 was another blow, although long expected. Most distressing were the deaths of Baldwin’s children, “the greatest blessing of human life.” “Sweet” Henry’s death in 1820 left William grief-stricken, as did his youngest son’s in 1829. In his will William would direct that his “mortal remains” be placed as close as possible to the latter “dear child.”

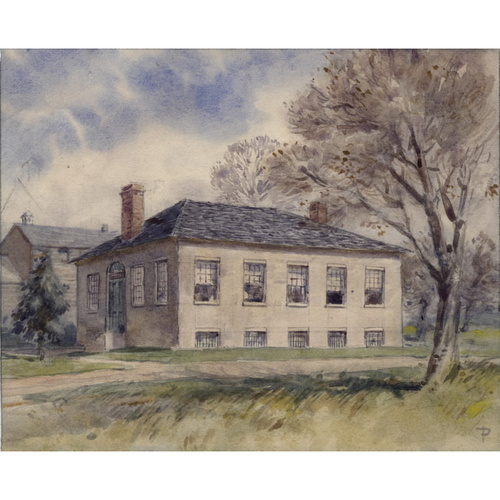

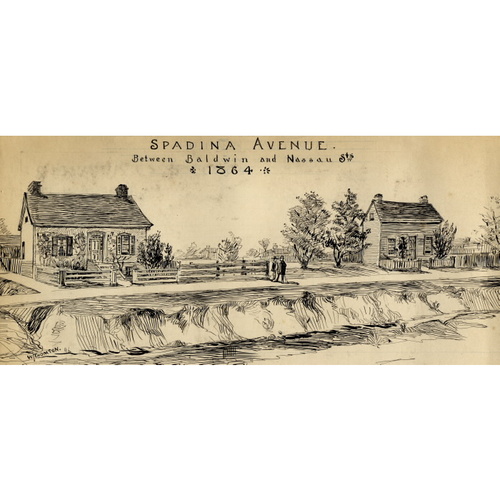

By contrast with his family life, William’s professional life was largely free of woe. It was not, however, necessarily easy. He travelled on the assize circuit, picking up business where he could and carrying out actions on behalf of various clients. In June 1814 he spent a few days at Ancaster, where the treason trials [see Jacob Overholser*] were in progress, but “I was not applied to in behalf of any of them.” Life on circuit was hard if not on occasion harrowing. A story is told of Baldwin’s becoming lost in the woods in 1815 and having to swim a swollen Credit River in the morning. Still, his practice was growing. He reckoned in 1819 that he cleared about £600 per annum, a sum sufficient – when combined with his emoluments of office and income from property – for him to have built the previous year a country house, which he called Spadina (“the Indian word for Hill – or Mont”), about three miles from York on land received as a gift from his father-in-law. Baldwin “cut an avenue through the woods all the way so that we can see the vessels passing up and down the bay.” When finished, with a stable and gardens, the house cost about £1,500. By 1819 he had three clerks in his law office: James Edward Small*, his nephew Daniel Sullivan, and Simon Ebenezer Washburn. The following year his son Robert joined the firm as a student-at-law and in 1823 his nephew Robert Baldwin Sullivan* began his articling period. Washburn was a partner from 1820, the year he was admitted to the bar, until 1825, when Robert was admitted to the bar and became a partner.

Commerce was the basis of any Upper Canadian legal practice and William’s was no exception. From 1815 he had, for instance, the principal responsibility for superintending the Upper Canadian enterprises of St George, who had returned to France. The following year he gave up the registrarship in the Court of Probate when he was appointed judge of the Surrogate Court, succeeding his father in this lucrative position. Estates inherited by the family and William’s astute management of them not only added to his office’s business but laid the basis for considerable wealth in the next generation. His wife and sister-in-law had inherited William Willcocks’s properties, and when Maria Willcocks died in 1834 her estate went to the Baldwin family. Maria and Phœbe also inherited the vast Russell tracts after Elizabeth Russell’s death. William himself was the heir to his father’s property. Land acquisition and estate management were vital to Baldwin’s prosperity and he amassed choice lots of both cultivated and uncultivated land. In the post-war years York was undergoing development [see John Ewart*] and the value of property there was increasing. Baldwin benefited. He had acquired valuable land in town, some lots through purchase, others from his father-in-law’s estate. By the 1820s he had become a large landowner and a wealthy man. His practice was now worth £700 a year while his wild (uncultivated) lands yielded an annual income of £1,400 (no figure is available for his rented farms or buildings but it was doubtless considerable). Although he lacked a single, large landed estate, he none the less closely approximated the English landed gentry in his ability to derive income from his holdings. He had all the trappings and attainments of gentility: education, refinement, a country home, and independent wealth. He was, as well, the doyen of his profession, holding the esteemed treasurership of the Law Society of Upper Canada for four separate terms (1811–15, 1820–21, 1824–28, and 1832–36).

But Baldwin’s stature in Canadian history has little to do with these accomplishments. Rather his eminence lies in his contribution to the development of the best known, and least understood, principle of Canadian political life, responsible government. Generations of Canadian historians have accorded the Baldwins, father and son, pride of place in the elaboration of the central doctrine of colonial evolution to nationhood, and of the transformation of empire into commonwealth.

For someone considered so essential to this process of political development, Baldwin became publicly involved with it rather late in his career, probably deliberately so. Before 1820 he was not without political opinions – his association with the pre-war opposition is evidence of that – but his views are difficult to discern. One notes, for instance, his agreement with Firth in 1812 that “a change of the Governor can effect but little change in the measures or deportment of the administration.” He undoubtedly shared Wyatt’s disappointment in Joseph Willcocks’s treason, but he applauded his castigation of “those who persecuted him.” He also shared in the dissatisfaction with the administration’s favouritism. Of Gore’s departure in 1817 one of Baldwin’s correspondents remarked, “It’s of very little consequence as the Scotch Party are at the Head yet and have it all among themselves.” This complaint – it had been a tenet of the pre-war opposition that Scots monopolized both offices and executive influence – was one with which Baldwin agreed. In 1813 he had related to Wyatt a pertinent incident. An altercation between officers of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment and a brother of Alexander Wood had resulted in criminal charges against the officers, and Baldwin defended them. When they were convicted of assault, he moved for an arrest of judgement but Chief Justice Thomas Scott* overruled him, levying “most unmeasured fines” on the officers. “Such,” Baldwin reasoned, “is the consequence of touching a Scottsman.”

His entry into politics came in the general election of 1820. Running in the riding of York and Simcoe and confident of success, or so Robert claimed, he was returned with Peter Robinson. Politically, the election came hard on the heels of Robert Gourlay*’s banishment, the prosecution of Gourlayite printer Bartemas Ferguson*, the dismissal from office of the president of the Gourlayite convention, Richard Beasley, and Robert Nichol*’s formidable leadership of the opposition within the House of Assembly. Baldwin considered that electors had solicited his candidacy “on the expectation of [his] rigid integrity towards the Constitution.” In a broadside he professed “an affectionate regard” for British liberty and the British constitution, and “to preserve the latter ever pure,” he declared, “the first must be preserved unwounded.” He promised to avoid factious opposition to “legitimate objects of the Administration” while maintaining “that the purest Administration requires a vigilant activity on the part of all its constitutional checks.” Thus William thought his victory had given “great public satisfaction to the independent part of the community & mortification to others.” Yet one historian who has analysed his conduct in this contest has depicted him as the eloquent defender of the administration, deeply grateful to it for office. The interpretation is exaggerated. Baldwin was “thankful” to the administration that “gave it, and the Government that has continued it to me” – nothing more. Two things are clear: first, Baldwin was sufficiently prosperous to risk estrangement from government; secondly, he was not yet of a mind that such estrangement was warranted.

Baldwin was neither a manager, nor an organizer, nor a leader in the day-to-day affairs of the eighth parliament (1821–24). Nichol resumed his leadership of the opposition, although Barnabas Bidwell* was a commanding presence for the one session he was in the house. Leadership for the administration was in the hands of Attorney General John Beverley Robinson* and his principal supporters, Christopher Alexander Hagerman and Jonas Jones. Compared to Baldwin, assemblymen such as John Willson* or Charles Jones spoke more often in debate and produced more legislation. Baldwin’s initiatives were usually confined to debate on topics that reflected his own priorities.

His privately expressed concern for the state of the economy took public shape as a motion proposing the formation of a committee to examine the agricultural depression and the collapse of British markets. The resulting committee on internal resources (which included Baldwin and was chaired by Nichol) tabled its report – the first attempt to devise a comprehensive provincial strategy for economic development – on 31 March 1821. Eight months later Baldwin supported Hagerman’s resolution for encouraging hemp production, a favourite policy of the executive since Hunter’s administration. Later still, in a manner calculated to advance the interests of a large landowner, he lamented “those restrictions, fees, and regulations, which operated equally against the poor as the Capitalist” in the administration of land grants, and he championed the principle that “capital ought to be blended with labour” to ensure prosperity. In 1824, and again in 1828, he was one of the most percipient critics of Robinson’s acts taxing the uncultivated lands of speculators such as Baldwin himself. On both occasions, he joined forces with the Niagara area merchants Thomas Clark* and William Dickson, who opposed the measures in the Legislative Council.

A gentleman who advocated a hierarchical society, Baldwin delivered in December 1821 the clearest enunciation of his aristocratic beliefs. The occasion was his attack on a bill sponsored by Bidwell and David McGregor Rogers* which would have eliminated the operation of primogeniture on intestate estates. This “visionary scheme,” more appropriate to a republic, “aimed at a total Revolution in the laws.” “Aristocracy, upon which the happy, happy Constitution of Great Britain rested, would be destroyed,” and he wished to see aristocracy “supported in this Colony to preserve the constitution . . . and not [to] run into a scheme of Democracy by establishing new fangled laws.” Robinson, the avatar of the ancien régime, was left with nothing to say but that he “agreed with every word.”

Baldwin was a whig constitutionalist whose ideas on law and politics were similar to those of the pre-war opposition led by Thorpe and Willcocks and the post-war opposition initiated by Nichol. His emphasis on limited government, retrenchment of expenditures, the independence of the constitution’s respective parts, and the civil rights and liberties of subjects was consistent with the country tradition in English politics. His first substantial speech in 1821 was on an attempt to repeal the Sedition Act of 1804, which – although it had been used only to banish Gourlay – had been a frequent target of Nichol’s since 1817. So long as it remained law, Upper Canadians were “without a constitution; at least a free one.” The act “remained in force, not only in the face of Magna Charta, but directly in the face of all the statutes made for the liberty and protection of the subject.” He then read to the house long passages from Blackstone on the liberties of subjects. Used against British subjects, he argued, the act was “arbitrary and tyrannical.” It undermined trial by jury, “the great land-mark in our constitution,” and was more cruel than “the Inquisition or Star Chamber.”

These utterances were commonplace and they serve only to locate Baldwin within the whig tradition. More important were his thoughts on Upper Canada’s constitution. He freely invoked the solemn authority of Blackstone on liberty but preferred Irish models for the question of the sovereignty of colonial legislatures. His remarks on this subject were prompted by the report of a joint committee of the assembly and the council on commercial intercourse with Lower Canada. Chaired by William Dickson and Robinson, the committee tabled its report (written by the attorney general) in December 1821. Baldwin had specific objections to it but his salient points were matters of principle: “it admitted as a principle that . . . this legislature cannot impose duties on imports”; “it acknowledges an incapacity in ourselves to govern . . . ourselves – & in effect gives our consent to surrender our Constitution [the Constitutional Act of 1791] back to British Parliament”; and “it does not in distinct terms present what we would wish – but leaves it to the discretion of the Imperial Parliament to do with us as it may please.” These principles were “subversive of every thing Valuable in our constitution. . . . The B. Parliament could not repeal that Law – the British Parlt can make and repeal the Laws of England because the parties to the making of the Law are the parties to the repealing of it, but not so here – that act gives legislative power to the inhabitants of this province – and the Law cannot be repealed without those inhabitants are parties to the repeal.” “But alas,” he added, “here is the point of dread.”

That point became clearer, as Baldwin had anticipated, during the debate in 1823 over a proposed union of the Canadas. In his view the Constitutional Act of 1791 conferred on the province’s inhabitants “the right to make laws for their peace, welfare and good government, reserving certain powers to the King and Parliament . . . to legislate in particular cases.” The imperial parliament, he argued, “could not constitutionally alter this law without our consent; for if so, we had no constitution at all.” The proposal for union had originated with a “commercial faction” in Lower Canada willing to trade “some speculative objects of imaginary advantages . . . in exchange for our Constitution.” Denouncing many of the clauses of the imperial union bill as “ruinous innovations,” he found “neither wisdom, good sense, nor justice evinced by the framers of that monstrous bill.” The most intriguing contribution to the debate was Baldwin’s statement that what the Canadas had received was not, as Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe* had often averred, “the image and transcript” of the British constitution, but rather the spirit of the constitution. Why, Baldwin wondered, would restless spirits abandon the Constitutional Act just as it was about “to change the French-man into the Englishman; or rather, as it was about to change the Frenchman into the Canadian; (for there might be, and there was, a Canadian Character distinct from the French, and though not English was yet properly reconcilable to and perfectly consistent with English feelings, English connection, and English Constitution;).”

Baldwin stood again for York and Simcoe in the election of 1824, placing a close third in a ten-man race and thus losing his seat. Unfortunately, that defeat eliminated his participation in assembly debates, the reporting of which provides historians with a valuable source for the study of Upper Canadian political thought during the tumultuous ninth parliament (1825–28). During this period, Baldwin turned his attention to what he began to see as partiality in the provincial administration of justice; in the process he became a partisan opponent of Sir Peregrine Maitland*’s government and of his chief advisers.

In 1818 William had written of Robert’s future, “I intend please God to bring him up to the bar.” There was no higher calling. When stepping down as treasurer of the Law Society in 1836, William detailed in his letter of resignation the special relationship of the constitution, parliament, and the law. As embodied in the 1791 act, the constitution was decidedly aristocratic, and Baldwin was not only one of its greatest admirers but also one of its greatest defenders. His willingness to duel for the sake of his honour and his ardent defence of primogeniture were tied to the natural, political, and social inequality he wished to preserve. He had defended in 1821 a bill enabling the Law Society to raise money for offices and a library to eliminate the necessity of new lawyers conducting their business in places “unfit . . . for gentlemen.” “There was,” he reasoned, “no Society for which the country should feel so deep an interest. . . . Without it, whose property was safe?” As he wrote in 1836, the society “has ever appeared to me of most importance to the preservation and due administration of our Constitution.” In a province lacking an aristocracy, the rule of gentlemen and the presence of a legal profession were indispensable. Crucial to gentility were rectitude, disinterested behaviour, and decorum; crucial to the legal profession was defence of the constitution and the rights which it entailed.

Baldwin’s address to the jury in 1827 during George Rolph’s civil suit against his assailants in a celebrated tar-and-feather incident is a specific example of Baldwin’s convictions. He was disturbed that Rolph’s tormentors, who were successfully defended by Allan Napier MacNab*, included several gentlemen prominent in the Gore District, “persons holding responsible offices, even occupying the seats of Justice – one of them entrusted . . . with the sword of Justice.” Subsequent events served to concentrate his attention on the administration of justice. Rolph’s case was followed by hotelier William Forsyth’s petition to the assembly in January 1828 complaining of Maitland’s substitution of military force for legal process “to decide the question of right” in a dispute that became renowned in opposition lore as the outrage at Niagara Falls. A select committee’s investigation led to a full-scale constitutional confrontation between Maitland and the assembly, which the lieutenant governor prorogued on 31 March. Then, in April at the York Assizes before John Walpole Willis*, the opposition journalist Francis Collins* reprimanded Attorney General Robinson for his partiality in the administration of justice.

In response to this charge Robinson, on 12 May 1828, sent out a letter to members of the bar raising the question of bias in his department. Baldwin replied on the 31st in a lengthy note. Although he had thus far “preserved a public silence,” Robinson’s circular compelled him “candidly” to state “wherein I thought you omitted your duty.” The first instance he cited was the attorney general’s failure “in some public and impressive manner [to] reprove your Clerks who were parties in” the riot which resulted in the destruction of William Lyon Mackenzie*’s press in 1826. Their conduct was “quite unbecoming Gentlemen and still more unbecoming them as Students at Law.” The printer’s conduct was “very bad” but Baldwin averred that his punishment should have been “reproof or prosecution,” not “outrage.” The assault on Rolph was another instance of dereliction of duty, Baldwin continued, and neither Robinson nor Solicitor General Henry John Boulton* could escape public censure for not “promptly and vigorously turning the Law against the perpetrators.” It was unconscionable in his view that Boulton might later act as the public prosecutor in a criminal action against the culprits, having already defended them against Rolph’s civil suit. He found the whole episode “so subversive of justice that I fully partook of the public disapprobation of that scene.” The last instance he cited was the 1822–23 case of Singleton Gardiner [see William Dummer Powell*], who had confronted two magistrates over the performance of statute labour. Abused by them, Gardiner, with Baldwin as his counsel, had launched a civil action against them. Robinson, acting as their attorney, insisted it was his duty to protect the justices. Baldwin agreed “wherein they are in the right; but my opinion also is that it is your duty to prosecute them wherein they are grossly wrong.”

Matters came to a head in June 1828. On the 16th Willis declared that, to function, the Court of King’s Bench required the presence of the chief justice and the two puisne justices. With Chief Justice William Campbell* on leave, only Willis and Levius Peters Sherwood were sitting. With the constitutionality of the bench in doubt, the Baldwins and Washburn wrote to Willis the following day enquiring if he would invite Sherwood’s consideration of the question and asking, in the event Sherwood’s opinion was not immediately forthcoming, if Willis would “withhold his Judgement” in any cases involving their clients, “untill as their Counsel we be better advised as to the course to be adopted.” On 23 June the Baldwins, in conjunction with John Rolph*, protested to Sherwood “against any Proceedings . . . until the Court be established according to the Provisions of the Provincial Statutes.” The issue was not merely a debate about “the strictest Principles of Law.” “There are no Laws,” they wrote, “demanding a more religious Observance than those which limit and define the Power of Individuals forming the Government over their Fellow Creatures.” The administration’s decision to remove Willis in late June precipitated a political reaction unlike anything the province had known, and the sense of crisis was fuelled by the impending general election in July. The Baldwins entered the fray, William in Norfolk and Robert in the riding of York. The elder Baldwin had been “required, and not invited” to run by John Rolph, who considered him “the only person . . . combining all that is desirable in a representative of a free people.” Although Robert lost, William was elected along with incumbent Duncan McCall*. Provincially the opposition gained a clear majority of members.

In York William was at the centre of a whirlwind of activity. During the campaign he had become, according to the pro-administration journalist Robert Stanton*, “a regular travelling Stump Orator.” Stanton thought him “mad” but Baldwin’s commitment to opposition was principled, and total. The legacy of the Willis agitation over the summer and fall of 1828 was multifold: formal reform organizations at York which would endure until the rebellion of 1837, sustained cooperation among pre-eminent reform leaders, and tactical planning by the opposition for the legislative session of 1829. William Baldwin loomed large in these developments as the elder statesman of the opposition coalition, and Robert was also prominent. It was not so much that the Baldwins needed other reformers; rather the reformers needed the Baldwins. The period was, after all, still the age of gentlemen, and the Baldwins were nothing if not gentlemen. And, as gentlemen, they were symbols of legitimacy for the broad reform alliance. Maitland put the point neatly in September 1828, describing Baldwin as “the only person throughout the Province, in the character of a gentleman, who has associated himself with the promoters of Mr. Hume’s projects,” his allusion being to the British radical Joseph Hume. The most perceptive opposition leaders, John Rolph and Marshall Spring Bidwell*, realized the importance of the Baldwins in this regard and used their organizational and manipulative talents to manœuvre the father and son into the positions to which their duty, as lawyers, Christians, and gentlemen, pointed.

Dr Baldwin addressed a constitutional meeting convened on 5 July 1828 to “complain of the arbitrary, oppressive, and high-handed conduct of the Colonial Executive” in removing Willis. The purpose of the meeting was, he said, to consider petitioning the king for redress of grievances. The alarm of those assembled sprang not from “unworthy or womanish fears” but from the concern of “men and patriots jealous of their rights and anxious to guard their liberties . . . from arbitrary power.” To acquiesce in the administration’s conduct would be tantamount to surrendering the constitution. He urged his listeners to be “watchful at election,” for the power was in their hands to return men independent of the executive. In language faintly reminiscent of his attack on the union, he suggested that the “legislatures of these Provinces have never been formed agreeable to the spirit of our constitution.” In Upper Canada, for instance, legislative councillors “are placemen and pensioners, depending upon the Executive for a living, instead of being an independent gentry.” He hoped the council would be remodelled, “odious” statutes repealed, and the “laws impartially administered.” Of his seven proposals for redressing the colony’s grievances, his sixth is of particular interest. He called for a provincial act “to facilitate the Mode in which the present constitutional Responsibility of the Advisers of the Local Government may be carried practically into Effect, not only by the Removal of these Advisers from Office when they lose the Confidence of the People, but also by Impeachment for the heavier Offences chargeable against them.”

It having been decided to memorialize the king, Baldwin presided at a meeting called on 15 August to draw up the petition. A number of resolutions were proposed and accepted. The critical 13th, moved by Robert, was an unequivocal summation of William’s position on the sovereignty of the Upper Canadian legislature: “That our constitutional act . . . is a treaty between the Mother Country and us . . . pointing out and regulating the mode in which we shall exercise those rights which, independent of that act, belonged to us as British subjects, and . . . that that act, being in fact, a treaty, can only be abrogated or altered by the consent of both the parties to it.”

William’s outstanding contribution to Canadian and imperial history is assumed by many historians to have been the idea of responsible government. Others have stressed his role in the transition from the idea of ministerial responsibility (that is, the legal responsibility of the king’s ministers to the legislature enforced by impeachment) to the idea of responsible government (which meant the political responsibility of individual ministers or the cabinet to the elected house), a change which supposedly took place in the thinking of Canadian reformers between 1822 and 1828. The former concept was commonplace in England by the 1760s, had been used by Thorpe and Pierre-Stanislas Bédard* before the War of 1812, and had been articulated by Nichol in 1820. So far as can be determined by the newspaper accounts of the debates of the eighth parliament (1821–24), Baldwin did not express himself on the matter, confining his remarks to the sovereignty of the colonial parliament as derived from its constitution; however, it would be fair to assume, given his statements on these questions, that he was familiar with the notion of ministerial responsibility. Both notions are present in his speech of 5 July 1828.

In a memorandum he penned in his copy of Charles Buller’s Responsible government for colonies (London, 1840), Baldwin gave an account of responsible government in Upper Canada, a “subject [that] well deserves complex elucidation in the way of an historical exposition of the evils, which early accruing and becoming inveterate led to its regeneration [there].” As the public documents for the early history of the province had, he thought, largely been lost, he began his history with a petition against union that he had drafted in 1822. He did so not because it touched on responsible government but because it presented evidence of the “constitutional rights then entertained by the people, in Contra distinction to the sentiments of the executive authorities . . . and of their dependents & partizans.” He moved to the resolutions of 15 Aug. 1828 as the next bench-mark in the development of the great principle. He then proceeded to his own letters to colonial authorities which “contain the development of the nature of the responsibility required and of the means of affecting it, after the example of the British Constitution; The suggestion in its distinct shape was made by Robert Baldwin . . . in private conversation with me on the occasion of penning those letters.”

William Baldwin had realized as early as 1812 that merely changing a governor did not necessarily change an administration. For a whig of an aristocratic bent, the Legislative Council was the means by which the mixed constitution was kept in balance and liberty preserved, and as late as July 1828 Baldwin seemed to be thinking of the constitution from that perspective. The new tack he adopted, whether originating with his son or not, necessitated acceptance of the executive’s political responsibility to the assembly, and from it to the electorate. The electorate at issue was not the British one limited to the world of gentlemen, however, but the Upper Canadian electorate based on close to universal manhood suffrage. The great question is, why did the Baldwins think such a principle would preserve a deferential and aristocratic society? The answer, if there is one, is not clear.

Behind the scenes, Rolph and Bidwell were exerting their influence on the elder statesman of reform. On 8 Sept. 1828 Bidwell suggested to William a conference to include Rolph “on the measures to be adopted to relieve this province from the evils which a family compact have brought upon it. . . . The whole system and spirit of the present administration need to be done away.” Baldwin relayed the message to Rolph who, “as one of His Majesty’s faithful opposition,” urged a concerted effort to choose the speaker for the forthcoming session of parliament as “a serious part of our cabinet arrangements.” He also hoped that the assembly under Baldwin’s “wise and prudent counsel . . . shall be enabled to carry the strongest measures and the most vital improvements.”

Copies of the August petition were circulated widely for signatures through the fall and early winter of 1828. On 3 Jan. 1829 Baldwin forwarded the accumulated petitions to the British prime minister, the Duke of Wellington, inviting his “thoughts to that principle of the British Constitution, in the actual use of which the Colonists alone hope for peace Good Government and Prosperity” as pledged by the Constitutional Act. The principle alluded to was the “presence of a Provincial Ministry (if I may be allowed to use the term) responsible to the Provincial Parliament, and removable from Office by his Majesty’s representative at his pleasure and especially when they lose the confidence of the people as expressed by the voice of their representatives in the Assembly; and that all acts of the Kings representative should have the character of local responsibility, by the signature of some member of this Ministry.” Once he had adopted this language and principle, Baldwin’s rhetoric became less moderate and more censorious. Bidwell had written to William on 28 May 1828 that “Power, unaccompanied with any real responsibility, any practical accountability, can never be confided safely to any man.” It seems reasonable to assume that the influence of Rolph and Bidwell, whose language was much sharper, much earlier, had had an effect in showing Baldwin how executive power could be made practically accountable.

Baldwin’s remarks in the house in early January 1829 on the speech from the throne highlight his new approach. Conveniently forgetting some of his own favourable statements, both private and public, about the Maitland administration, he now lumped together successive administrations from Simcoe’s onward and lashed them for their pursuit of “the same injurious course.” He also described as “evil” the advisers who had tried to foist union on the province. The assembly should, he thought, “be considered the great Council of the country.” In a private letter to Robert on 25 January he listed the evil advisers, some of whom were on the Executive Council: Robinson and his brother Peter, John Strachan*, Henry John Boulton, and James Buchanan Macaulay*. They should be “dismissed from office and from the Cabinet Council – this term might be adopted with advantage.” Terms such as this one he was picking up from Rolph and Bidwell. In the debate on the speech from the throne he had urged Rolph’s appointment “at the top of the Treasury Bench as it had been called.” It had been called that minutes earlier by Rolph himself. On the abstract level, Baldwin noted in the house that the assembly “should be placed on the same footing as the House of Commons . . . otherwise those who sat in it could not properly be called the Representatives of the people.” Responsible government made the executive accountable to the assembly – suggesting parties even in an inchoate state – and the electorate. In 1836 he was to write to Robert, “It was no matter what the parties were called, whig or tory – parties will be, and must be . . . therefore it becomes important [for the executive] to have the concurrence of the Assembly.” A year after the throne debate, Baldwin suggested to Joseph Hume four means for remedying the evils of Upper Canada: control of revenues by the assembly, exclusion of the judiciary from the councils, reorganization of the Legislative Council (but not on an elective principle), and the “formation of a new executive or Cabinet Council, responsible and removable as the public interest may demand – which it is anticipated would of itself indirectly lead to the removal of all our present grievances & prevent the recurrence of any such for the future.”

William and Robert both contested their seats in the election of October 1830 and lost. Bitter, William withdrew from political life. In 1831 he seems to have retired from his law practice, or at least let Robert and his new partner, Robert Baldwin Sullivan, assume the greater part of the burden. That same year he and Phœbe moved back into York to live with Robert and his family. The “extreme fickleness of popular opinion” at elections weighed on his mind and in 1834, when offered an opportunity to participate in a political meeting, he declined. His public role was not in eclipse, however. The gentlemanly Baldwins were attractive to conciliatory administrators as the right sort of oppositionists. Both were considered for the Legislative Council in 1835, but neither was appointed. In that year Spadina was razed by fire. A smaller house would be erected on the site; William was also to design and build a large Georgian-style mansion in town.

The arrival of a new lieutenant governor in Toronto on 23 Jan. 1836 stirred reform hopes. Sir Francis Bond Head* made overtures to the opposition by reconstructing the Executive Council. After numerous negotiations, Head brought Robert Baldwin, Rolph, and John Henry Dunn* into the council. William, whose name had come up, was not interested. He was convinced that the answer to the colony’s problems was “a responsible Government through the medium of the Executive Council . . . discharging its duties in the way analogous to the Cabinet Council of the King in England.” The council’s subsequent resignation in March hurled the province into its most serious political-constitutional crisis since the Willis affair. Robert, whose wife had died on 11 January, headed off to England and Ireland to be alone with his grief while William superintended family matters at home and witnessed the political desertion in March of his brother Augustus Warren* and of his nephew Robert Baldwin Sullivan to Head’s council, into the arms of the “Tory junto” as he put it.

Meanwhile, no doubt at the urging of a neighbour, Francis Hincks*, Baldwin joined the executive committee of the Constitutional Reform Society of Upper Canada, where he consorted with William John O’Grady, Rolph, and others. He was given the most distinguished positions: he became president of the society and was also made chairman of the Toronto Political Union. That July Head dismissed him as district and surrogate court judge, citing as reason his signature as president on a reform society document upholding the basic doctrines of reformers. William denounced the election of July 1836 as Head’s “vicious triumph over the people.” Head believed Baldwin knew of the preparations for the rebellion of 1837, but Baldwin denied it and Mackenzie later corroborated his statement. On 1 Jan. 1838 Baldwin published a letter indicating his position. “Great reform” was still required but it must be “lawful and constitutional.” His political activity after the election of 1836 had been “solely directed to the means of discovering the facts of unconstitutional interference in behalf of Government.” When the discussions of reform groups proved “unproductive,” he no longer went to meetings and could not recollect having attended any since Robert’s return from England in February 1837. He deplored the “rash insurrection” which had the effect of “silencing for many years to come, the voice of Reform, even the most rational and temperate.” As for the Patriot incursions, he considered them foreign invasions and was willing to take up arms against them.

Many remedies were put forward in the 1830s by various reformers to eliminate the evil rule of what most considered a corrupt oligarchy. Responsible government, the favourite of the Baldwins, was but one, albeit the least threatening – or so the Baldwins thought – to the constitution, the social order, and the British connection. William understood oligarchy in terms of classical political philosophy: it was the degenerate, or unconstitutional, form of aristocracy. He believed, even in mid 1836, that the political contention within the upper province was related “to the mere administration of affairs”; in Lower Canada, it concerned the actual “form of government.” The failed rebellion eliminated more radical proposals while elevating the status of the Baldwins’ moderate principle. In fact, a gesture in their direction was considered in 1835 and proffered in 1836. The Baldwins had a brief interview with Governor Lord Durham [Lambton] during his July tour of Upper Canada in 1838. By this time responsible government and the voluntary principle with respect to church and state had become the key articles of reform canon [see Francis Hincks]. The reformers’ chief desire, articulated by Hincks in the Examiner of 18 July, was that the lieutenant governor “administer the internal affairs of the Province with the advice of a responsible provincial cabinet, and not under the influence of a Family Compact, as at present.” On 1 August William sent Durham, as did Robert, a long letter “on the subject of public discontent.” Among the 20 causes he listed were the crown and clergy reserves, the land-granting department, the monopoly of the Canada Company [see Thomas Mercer Jones*], interference by the executive in elections, revenues of the executive independent of the assembly, parliamentary obstruction by the Legislative Council, the encouragement of Orange societies, and the “extravagant waste” on projects such as the Welland Canal [see John Macaulay*]. His chief recommendation was the application of “English principles of responsibility . . . to our local Executive Council.” Implementation of those principles came bit by bit.

William was now too old to participate actively in politics and was content to advise the chief standard-bearer of responsible government, Robert. William’s understanding of the idea had been certain for some time, and it would not change. He thought it was “conceded” by Colonial Secretary Lord John Russell’s dispatch of 10 Oct. 1839 [see Robert Baldwin]. And he held out high hopes initially for Governor Charles Edward Poulett Thomson’s plans for a reconstituted Executive Council of the soon-to-be united province. In the late 1830s his descriptions of politics evolved, as they had in 1828, into increasingly harsh portraits. Head’s interference in the election of 1836 was without parallel: “There could not be devised . . . by the most despotic Government a more wicked scheme of oppressing us.” By June 1841 he saw politics as an “important struggle between good Govt. and evil govt.” Several months later the contest had acquired Manichean tones: “I really believe the fight is with the powers of darkness.” And he meant it. The “horrible violence from the Tories” which had so astonished him during the Yonge Street riot of November 1839 seemed to have acquired a permanency which was, as late as 1843, still upholding the “old vile Tory system.”

William was an Anglican of deep personal faith, intolerant of the Orange order – he had tried to legislate its suppression in 1823 – and the clergy reserves, but tolerant of dissenters and Roman Catholics. He shared with most of his contemporaries a providential faith which focused increasingly by the late 1830s on Robert’s appointed role in the divine plan. “God will direct you,” he wrote to him in 1841, “therefore you cannot err.” Robert believed him and agonized even more over every decision. In his will of 1842 William, who still believed firmly in primogeniture, left almost everything to Robert, explaining his decision to Phœbe in this way: “One child only can be born first – and this in all time and societies . . . has been received as the appointment of Providence. . . . It tends to preserve a reverence for the institutions of our ancestors, which though always tending to change, for by nature all human affairs must change, yet resist innovations but those only which are gradual and temperate.” Perhaps William’s greatest legacy was the deep personal impression he made upon his eldest son. After his father’s death in 1844 Robert wrote: “Those only who knew him intimately can appreciate the loss which we have sustained in the death of such a parent – All that is left us is to honour his memory by endeavouring to imitate his example.” And honour it Robert did.

William Warren Baldwin had had a variety of social and cultural concerns. A wealthy man, he subscribed to most philanthropic bodies, and he was a director of the Bank of Upper Canada, manager of the Home District Savings Bank, and a member of both the Medical Board of Upper Canada and the York Board of Health. He was also an early president of the Toronto Mechanics’ Institute, a member of St James’ Church, and an advocate of missionary work among the Indians. Charles Morrison Durand, a Hamilton lawyer, remembered him as a “haughty, prejudiced, Protestant Irish gentleman . . . very rough and aristocratic in his ways.” Although warm to his family, he had an aloofness that reflected a tough inner core. He knew this quality in himself. “I seem to myself quite hard – when I witness the distress of those around me – what a strange comportment is Mine – I really know nothing of myself – I wish a friend could tell me – and yet I would shrink from his candour.”

[The cooperation of J. P. B. Ross and Simon Scott, who allowed access to their papers, is deeply appreciated. Acknowledgment is also due to my partner in Baldwin research, Michael S. Cross.

References to William Warren Baldwin may be found in most private manuscripts and government collections relating to the period. The essential sources are the Baldwin papers and the Laurent Quetton de St George papers at the MTRL and the Baldwin papers at AO, ms 88. The Baldwin–Ross papers at PAC, MG 24, B11, 9–10, as well as the private collection of Ross–Baldwin papers belonging to Simon Scott, are also useful. Important to this study were contemporary newspapers, among which the following were most helpful: Canadian Freeman, 1825–33; Colonial Advocate, 1824–34; Constitution, 1836–37; Examiner (Toronto), 1838–44; Kingston Chronicle, 1820–33, and its successor Chronicle & Gazette, 1833–36; Upper Canada Gazette, 1819–24; and Weekly Register, 1823–24.

Among the more thoughtful treatments of responsible government in Upper Canada are three articles by Graeme H. Patterson: “Wiggery, nationality, and the Upper Canadian reform tradition,” CHR, 56 (1975): 25–44; “An enduring Canadian myth: responsible government and the family compact,” Journal of Canadian Studies (Peterborough, Ont.), 12 (1977), no.2: 3–16; and “Early compact groups in the politics of York” (unpublished); and two by Paul Romney: “A conservative reformer in Upper Canada: Charles Fothergill, responsible government and the ‘British Party,’ 1824–1840,” CHA Hist. papers, 1984: 42–62; and “From the types riot to the rebellion: elite ideology, anti-legal sentiment, political violence, and the rule of law in Upper Canada,” OH, 79 (1987): 113–44. With these notable exceptions, studies of responsible government have largely isolated British North American politics from its English background. The literature here is enormous. J. C. D. Clark, Revolution and rebellion: state and society in England in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Cambridge, Eng., 1986), is a helpful place to start. Especially worthwhile are John Brewer, Party ideology and popular politics at the accession of George III (Cambridge, 1976), H. T. Dickinson, Liberty and property: political ideology in eighteenth-century Britain (London, 1977), and J. G. A. Pocock’s stimulating collection of essays, Virtue, commerce and history; essays on political thought and history, chiefly in the eighteenth century (Cambridge, 1985). One of the few attempts to study the development of Canadian political culture is Gordon T. Stewart’s thought-provoking book, The origins of Canadian politics: a comparative approach (Vancouver, 1986). The best work on the Colonial Office, imperial policy, and English politics as they bore on the colonies is Buckner, Transition to responsible government.

There is no full-length study of Baldwin’s life but aspects of it are dealt with in G. E. Wilson, The life of Robert Baldwin; a study in the struggle for responsible government (Toronto, 1933); R. M. and Joyce Baldwin, The Baldwins and the great experiment (Don Mills [Toronto], 1969); and J. M. S. Careless’s “Robert Baldwin” in the volume he edited, The pre-confederation premiers: Ontario government leaders, 1841–1867 (Toronto, 1980), 89–147. M. S. Cross and R. L. Fraser, “‘The waste that lies before me’: the public and the private worlds of Robert Baldwin,” CHA Hist. papers, 1983: 164–83, is also useful.

A fine portrait of Baldwin held in the Royal Ont. Museum, Sigmund Samuel Canadiana Building (Toronto), is reproduced opposite p.48 of the study by R. M. and Joyce Baldwin. r.l.f.]

Cite This Article

Robert L. Fraser, “BALDWIN, WILLIAM WARREN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 26, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/baldwin_william_warren_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/baldwin_william_warren_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert L. Fraser |

| Title of Article: | BALDWIN, WILLIAM WARREN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1988 |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | December 26, 2025 |