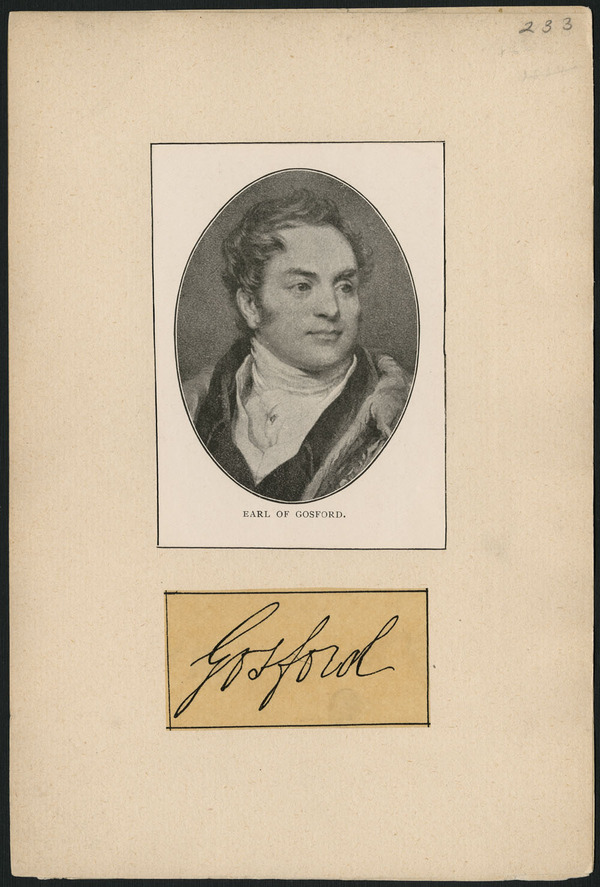

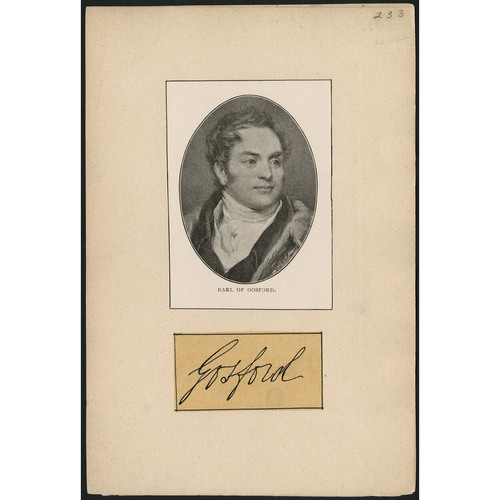

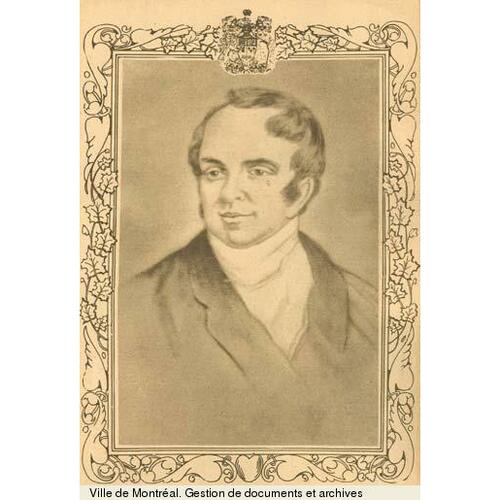

ACHESON, ARCHIBALD, 2nd Earl of GOSFORD, colonial administrator; b. 1 Aug. 1776 in Ireland, eldest son of Arthur Acheson, 1st Earl of Gosford, and Millicent Pole; m. 20 July 1805 Mary Sparrow in London, and they had one son and two daughters; d. 27 March 1849 at his estate in Markethill (Northern Ireland).

Archibald Acheson came from a family of Scottish Protestant origin settled in Ireland since 1610. Like the sons of many Irish peers, he received an English education, the University of Oxford awarding him a ba in 1796 and an ma, the following year. During the suppression of the Irish rebellion of 1798 he served as a lieutenant-colonel in the militia of County Armagh (Northern Ireland). That year he was elected to the Irish House of Commons from the family seat in this county. In 1800 he vainly opposed the act uniting Ireland and Great Britain, by the terms of which he became a member of the British House of Commons in 1801. He surrendered his seat in 1807 on succeeding his father as Earl of Gosford, and in 1811 he was elected to the House of Lords as an Irish representative peer. A brother-in-law of Lord William Cavendish Bentinck, he was connected to a powerful Whig family, and he consistently supported the Whigs in parliament. After they came to power, he received several appointments.

Although Gosford had been born into the Protestant establishment and defended “the Protestant cause,” he favoured sharing power in Ireland with the Catholic majority. In 1825 he opposed a bill to outlaw the Catholic Association, led by Daniel O’Connell. Four years later he voted for Catholic emancipation, and in 1833 he defended the Whig government’s assault on the privileges of the established Church of Ireland. He also supported the Whig program of introducing more Catholics into the magistracy. Known as “a good hearted, amiable and liberal gentleman,” he voted for the Reform Bill of 1832 and in 1833 with the minority for the emancipation of the Jews. He was an outspoken critic of the Orange order, which he blamed for much of the religious friction in Ireland. As lord lieutenant of County Armagh from 1831 he sought to preserve peace, at a time of increasing violence, by relying on the recently formed Irish constabulary rather than on regular troops. Accused in the Commons of showing favouritism to Catholics, he was defended by Joseph Hume and by O’Connell, who declared that he had displayed “a total absence of party spirit.” Since the Whigs depended on the radicals and the Irish party in that house, Gosford’s popularity with both groups partly explains his appointment on 1 July 1835 as governor-in-chief of British North America. But he was also selected because the ministers hoped that he might be able to apply in Lower Canada the techniques of conciliation that he had employed so successfully in Ireland. For agreeing to accept the appointment he had been made Baron Worlingham in the United Kingdom peerage on 13 June.

A civilian, unlike his predecessors, Gosford was not made commander of the forces in the Canadas, but he was given unusually extensive authority over the lieutenant governors of the neighbouring colonies, who were sent copies of his instructions. He was also placed at the head of a commission of inquiry into political problems in Lower Canada, on which his colleagues were Sir Charles Edward Grey, a former judge in India, and Sir George Gipps, who had served in the West Indies; Thomas Frederick Elliot, in charge of the North American Department at the Colonial Office, was seconded as secretary and became in everything but name a fourth commissioner. Their instructions from the colonial secretary, Lord Glenelg, emphasized that the commissioners were on a “mission of peace and conciliation.” The function of the commission was to find a solution to the conflict between the executive and the House of Assembly which had virtually paralysed government in Lower Canada, although interference by King William IV limited the freedom of action of the commissioners by preventing them from discussing the merits of making the Legislative Council an elective body.

Gosford assumed control of the government of Lower Canada on 24 Aug. 1835. Because his predecessor, Lord Aylmer [Whitworth-Aylmer], had become identified with the English, or Constitutionalist, party, Gosford kept his distance from Aylmer until the latter’s departure the following month. Subsequently he held a series of lavish dinner parties and balls, at which he established a reputation as a bon vivant and showered his attentions on the leading members of the Patriote party and their wives. Viewed with suspicion by many Patriotes, Gosford was nevertheless sufficiently popular when the assembly met in October 1835 to prevent their leader, Louis-Joseph Papineau*, from persuading the house to disband until all of the points in the 92 Resolutions were conceded. His speech opening the legislature had promised reforms “with alacrity, impartiality and firmness.” During the session he responded favourably to 67 of the 72 addresses of the assembly and reserved only 1 of 59 bills. For his actions he was castigated in the anglophone press – particularly by the editor of the Montreal Herald, Adam Thom*, in a series of abusive “Anti-Gallic” letters. Yet Papineau and his followers were annoyed when Gosford refused to dismiss a number of unpopular officials until a full and impartial investigation had been made of their conduct. None the less, Gosford did succeed in co-opting the support of a number of moderate Patriotes [see George Vanfelson*], and he predicted that the assembly would vote supplies.

This assumption lay behind the first report of the Gosford commissioners, in January 1836, dealing with the critical issue of colonial finances. The report was drafted by Gipps, Gosford’s intermediary in negotiations with the Patriotes over supplies and a dominant figure on the commission. Believing “the inordinate power” of the assembly to have grown out of “unwise resistance” to that house on untenable points, Gipps recommended that all crown revenues be surrendered to the assembly in return for an extremely modest civil list. In what was to become a familiar pattern, the commissioners divided; Gosford and Elliot endorsed the proposal, but Grey insisted that a much larger civil list was necessary to secure the independence of the executive and to quiet the legitimate fears of the British minority. The assembly never seriously considered the report. Early in 1836 the newly appointed lieutenant governor of Upper Canada, Sir Francis Bond Head*, released to the Upper Canadian assembly his text of Gosford’s instructions. When it became known in Lower Canada that the commissioners could not accept an elective legislative council or surrender the revenues of the crown unconditionally, many moderate Patriotes drifted back into Papineau’s fold. In February the feelings of the assembly “underwent a sudden change”; the house refused to vote arrears in salary due to office holders, who had gone unpaid for nearly three years, passed a six-month supply bill so objectionable that it was inevitably rejected by the Legislative Council, and reiterated its commitment to the 92 Resolutions. In March Papineau and his supporters withdrew, leaving the assembly without a quorum. Gosford prorogued the legislature on 21 March and used the casual and territorial revenues to defray the most pressing expenses. A satisfactory adjustment of the financial crisis was, he admitted, “as distant and more hopeless than ever.”

The second report of the commissioners, prepared in mid March 1836, reflected this gloomy prognosis. They realistically predicted that the assembly would never vote supplies unless all its demands were met, but felt that to yield to those demands would establish “a French republic in Canada.” Consequently they recommended that the Revenue Act of 1831, which had surrendered to the legislature control over the substantial revenues reserved to the crown by the Quebec Revenue Act of 1774, should be repealed to place at the disposal of the executive sufficient funds to carry on the essential services of government. The commissioners disagreed over the details; Gosford, Gipps, and Elliot believed that repeal should be for a limited time to persuade the assembly to reconsider its position, while Grey wished to make it indefinite. In London, Lord Howick, the secretary at war who, as colonial under-secretary in 1831, had drafted the bill and guided it through parliament, coerced Glenelg into refusing to repeal the act. Howick felt that the divisions among the commissioners had destroyed their usefulness, but he failed to persuade cabinet either to replace them with “a really able Governor” having large powers and clear instructions or to issue them with instructions that offered a better chance of successful negotiations with the assembly. Howick’s negative influence left Gosford at the mercy of the assembly for supplies but unable to accept its conditions for a supply bill.

Gosford persevered in efforts at conciliation. In February 1836 he appointed Elzéar Bédard, who had moved the Patriote party’s 92 Resolutions in the assembly, to a vacant judgeship, even though Bédard ranked 24th in seniority among lawyers at the bar. That April he submitted to Glenelg a list of ten candidates for the Legislative Council; seven were drawn from the majority party in the assembly. He also wished to alter the membership of the Executive Council, in which he had little confidence. At the beginning of May the commissioners, in their third report, rejected the concept that the Executive Council should be responsible to the assembly but suggested that its members should hold office at the discretion of the governor and not during good behaviour. As usual, Grey dissented; he feared that such a measure would force the governor to select his advisers from the dominant party in the assembly. Wishing to restructure the council immediately, on 5 May Gosford submitted to Glenelg a list of 14 candidates, including such prominent Patriotes as René-Édouard Caron*, Hector-Simon Huot, Pierre-Dominique Debartzch, and Augustin-Norbert Morin*, all moderate Patriotes with the possible exception of Morin, who, increasingly, was adopting Papineau’s views. During the summer of 1836, while awaiting the results of his recommendations, Gosford embarked upon an extensive tour of the province, and he reported that “I never was in a Country where comfort was so generally diffused & its inhabitants so peaceable, happy, & contented.” When Glenelg’s instructions arrived, Gosford learned to his dismay that the colonial secretary would make no changes in the councils before the commissioners had completed their investigations and a comprehensive settlement could be offered to the assembly. On 22 September Gosford reconvened the legislature but on the 30th the assembly adjourned its proceedings until all its demands were met. Gosford prorogued the legislature and pointed out to Glenelg that important acts dealing with trade and banking would expire unless the imperial government intervened.

On 15 Nov. 1836 the Gosford commissioners completed their final report. They concluded that Britain would not be justified in altering the electoral system in the colony to increase the number of British representatives in the assembly. On the other hand, they insisted that since an elective legislative council was opposed by the British and would not, alone, satisfy the French Canadians, only minor reforms and new appointments should be made. Aware that this decision would antagonize the assembly, the commissioners reiterated that the Revenue Act of 1831 must be repealed to provide the executive with funds. They also recommended that parliament reject the extreme demands of the assembly. Predictably, Grey submitted his own report, arguing for substantial change in the electoral system to give greater weight in the assembly to the British minority.

After a lengthy debate, the cabinet accepted the Gosford commission’s recommendations except that for repeal of the revenue act. On 6 March 1837 Lord John Russell introduced into the Commons ten resolutions embodying the government’s program. They combined a small dose of coercion with a substantial measure of conciliation. The government did not ask parliament to give the executive a permanent source of revenue but only authority to pay from the colonial treasury arrears owed to civil servants. Glenelg promised that in future only the casual and territorial revenues would be used to defray expenses for which the assembly would not provide. The only other interference with the powers of the assembly was to be a measure extending the duration of unrenewed commercial and banking laws. Several resolutions, such as a promise not to establish land companies without the approval of the assembly, emphasized the government’s desire to reach an accommodation. Although the government declared its opposition to an elected legislative council and a responsible executive council, it promised to implement the reforms recommended by the Gosford commission.

In June 1837 Gosford again submitted the names of his nominees for the councils. Although he dropped several earlier candidates because of their outspoken opposition to the Russell resolutions, the majority of those he proposed were from the Patriote party, and he predicted that if these appointments were confirmed, the assembly would vote supplies. However, Glenelg’s dispatch of confirmation did not reach Gosford until after the assembly, convened to give it an opportunity to vote supplies and thus forestall parliamentary appropriation of colonial funds, had met, refused supplies, and been prorogued.

Gosford was neither a good-natured incompetent nor the “vile hypocrite” that his critics proclaimed. He hoped to create in Lower Canada an alliance of moderate politicians from both parties and to hold the balance of power as the Whig administration did in Ireland between Catholics and Protestants. Whig policy there was to distribute patronage to Catholics and liberal Protestants in order to remedy an historic imbalance in the higher levels of the administration. Gosford pursued the same goal. He increased appointments of French Canadians to the judiciary and the magistracy, insisted that a chief justice and a commissioner of crown lands should be chosen from among them, and gave them a majority on the Executive Council and a virtual majority on the Legislative Council. He substantially increased their numbers holding offices of emolument. Moreover, he refused to allow multiple office-holding, to condone nepotism, or to appoint to prominent positions persons known to be antipathetic to them. But Lower Canada was not Ireland. In the 1830s O’Connell and the Catholic élite cooperated with the Whigs because they realized that confrontation with imperial authority was doomed to fail; lacking O’Connell’s understanding of imperial politics and spurred on by English radicals, such as John Arthur Roebuck*, Papineau demanded that his party be given control over the colony through the assembly, and he foolishly believed that Britain would yield. Aware of Papineau’s extremism, Gosford continued efforts to undermine his leadership by persuading the élite among French Canadians that moderation and power-sharing would achieve most of their goals. He skilfully exploited divisions within the Patriote party, an alliance of regional and local politicians differing among themselves over the extent to which the party should carry confrontation. During his first year he had co-opted politicians from Quebec. He also successfully exploited antagonism between radical Patriotes and the Roman Catholic hierarchy, by working harmoniously with Jean-Jacques Lartigue, whom he confirmed as the first bishop of Montreal, and Ignace Bourget*, whom he approved as Lartigue’s coadjutor. Yet he failed to wrest control of the assembly from Papineau, although his tactics probably helped later to limit support for rebellion.

The vacillation of the Whig government undoubtedly contributed to Gosford’s failure by confirming for many Patriotes the belief that Britain would cave in. Even without this handicap, however, Gosford was unlikely to have succeeded. He had consistently underestimated support for Papineau. Moreover, after passage of the Russell resolutions, co-opting moderates was of diminishing utility since he could not appoint to office those who rejected the resolutions, and French Canadians who defended them were marked as vendus. By the summer of 1837 the government could no longer maintain order in the countryside. In September Gosford dismissed 18 magistrates and 35 militia officers for attending meetings at which civil disobedience was advocated. The following month he conceded that the constitution would have to be suspended, and in November he submitted his resignation and recommended that a new governor be appointed with the authority to declare martial law.

As the government lost control in the countryside, the natural alliance between the executive and the British minority reasserted itself. Gosford viewed the English party as akin to the Orange Order in Ireland. In 1835 and 1836 he had publicly denounced the organization of rifle clubs and volunteer cavalry units by Constitutionalists in Montreal and Quebec. Later, he exploited a split in the English party between supporters and opponents of the privileged position of the established church by recommending that the clergy reserves should be applied to general education and not given solely to the Church of England. However, as the magistrate system began to collapse in 1837 the English party closed ranks, shunting the moderates aside, and Gosford was increasingly urged to seek its assistance in maintaining order. Had a larger force of British troops or an equivalent to the Irish constabulary been available, he might have resisted, but the military force in the Canadas in early 1837 was only 2,400 regulars. Although at first reluctant to increase its size, Gosford used his discretionary authority in June to transfer a regiment from Nova Scotia, an action that infuriated the commander in the Canadas, Major-General Sir John Colborne*. By October Colborne too had accepted that additional troops were needed, and Gosford requested them from the Maritimes. Under pressure from his military advisers, Gosford in November unofficially sanctioned defence preparations by the British minority. Indeed, his resignation was based in part upon the knowledge that he was persona non grata with the English party, whose support might be needed if a rebellion took place.

On 16 Nov. 1837, convinced that the Patriotes’ grievances were “mere pretexts to clothe deeper, and darker designs,” Gosford reluctantly issued 26 warrants of arrest, including one for Papineau; they supplied the spark that touched off rebellion one week later at Saint-Denis, on the Richelieu [see Wolfred Nelson*]. In December Gosford subjected the district of Montreal to martial law. To his credit he tried to contain the forces he had been compelled to unleash. He pleaded with Colborne to revert to civil law wherever possible. In late December, when the rebellion appeared crushed, he freed 112 habitants as an act of clemency. Although he agreed to trial by court martial for rebel leaders, he urged Colborne to proceed “with the greatest possible caution.” He would not allow reprisals by the English party or persecution of non-participants.

In January 1838 Gosford learned that his resignation had been accepted. By then he was an isolated and somewhat pathetic figure. His only allies and regular companions were a few moderate French Canadians, particularly Elzéar Bédard and Étienne Parent*, editor of Le Canadien (Québec). He felt betrayed by Glenelg. Following termination of his appointment as a special commissioner on 18 Feb. 1837, his salary alone proved unequal to his many official expenses. He suffered increasing discomfort from gout. After a delay caused by a fall on the ice, he departed on 27 Feb. 1838, when Colborne formally took control of the administration.

Back in England, Gosford was given a vote of thanks by the Whig ministry and awarded the gcb (civil division) on 19 July 1838. He did not lose interest in Canada. On the appointment of Lord Durham [Lambton] as governor he commented that “a more judicious choice could not have been made.” He wrote to Durham that the majority of French Canadians had not participated in the rebellion and warned against the English party. As Durham’s ethnocentricity became more pronounced, Gosford criticized him bitterly for appointing to office such outspoken opponents of French Canadians as James Stuart* and Peter McGill*. Indeed, Gosford blamed the second rebellion, in the autumn of 1838, on Durham’s stupidity, and he was equally critical of Colborne and “those savage Volunteers.” When Colborne suspended from office three francophone judges, Bédard, Philippe Panet*, and Joseph-Rémi Vallières de Saint-Réal, Gosford defended them at the Colonial Office and arranged for each a 12-month leave of absence at full pay. He considered the union bill of 1840 “unjust” and “arbitrary” and presented in the House of Lords a petition from Lower Canada opposing it. During the 1840s his interests again focused on Ireland, where he split with O’Connell over the issue of repeal. In his declining years he devoted his primary attention to his estates.

Gosford had left Lower Canada little loved either by the British minority or by the Patriotes. The British government ignored his advice and followed the recommendations of Durham, who declared that Gosford was “utterly ignorant . . . of all that was passing around him.” The assessment is unjust. Gosford had shown considerable administrative ability, more political sensitivity than his predecessors, and greater tolerance than his immediate successors. His sincerity is unquestionable. He probably did as much to limit the severity of the rebellion as it was possible to do, and if Durham had followed his advice, the second rebellion might have been considerably less bloody. That Gosford failed to achieve his goals is self-evident; that he ever had a reasonable chance of success is doubtful.

A portrait of Archibald Acheson, 2nd Earl of Gosford, which he presented to Jean-Jacques Lartigue at the latter’s request, is reproduced in Joseph Schull, Rebellion: the rising in French Canada, 1837 (Toronto, 1971).

National Library of Ireland (Dublin), Dept. of mss, mss 13345–417 (Monteagle papers). NLS, Dept. of mss, mss 15001–195. PAC, MG 24, A17, A19, A25, A27, A40, B1, B36, B37, B126, B127, C11. PRO, CO 42/258–80; CO 43/31–33. Univ. of Durham, Dept. of Palaeography and Diplomatic (Durham, Eng.), Earl Grey papers. Camillus [Adam Thom], Anti-Gallic letters; addressed to His Excellency, the Earl of Gosford, governor-in-chief of the Canadas (Montreal, 1836). G.B., Parl., Hansard’s parliamentary debates (London), [2nd] ser., 12 (1825), 3 March; 22 (1830), 26 Feb.; 3rd ser., 2 (1831), 21 Feb.; 3 (1831), 22 March; 19 (1833), 17 July; 20 (1833), 1 Aug.; 27 (1835), 14 May; House of Commons paper, 1835, 15, no.377: 229–99, Report from the select committee appointed to inquire into the nature, character, extent and tendency of Orange lodges, associations or societies in Ireland. . . . L.-J.-A. Papineau, Journal d’un Fils de la liberté. Quebec Gazette, 14 Oct. 1835; 4, 8 Jan. 1836. Times (London), 7 April 1836, 30 March 1849. Vindicator and Canadian Advertiser, 30 Oct. 1835. Burke’s peerage (1970). Complete baronetage, ed. G. E. Cokayne (5v., Exeter, Eng., 1900–6). DNB. R. B. Mosse, The parliamentary guide: a concise history of the members of both houses (London, 1835). George Bell, Rough notes by an old soldier, during fifty years’ service, from Ensign G.B. to Major-General C.B. (2v., London, 1867). G. C. Bolton, The passing of the Irish Act of Union: a study in parliamentary politics (London, 1966). Buckner, Transition to responsible government. Chaussé, Jean-Jacques Lartigue. Christie, Hist. of L.C. (1848–55), vols.3–4. G. P. Judd, Members of parliament, 1734–1832 (Hamden, Conn., 1972). W. E. Lecky, A history of Ireland in the eighteenth century (new ed., 5v., London, 1892), 4: 320–21. R. B. McDowell, Public opinion and government policy in Ireland, 1801–1846 (London, 1952). Ouellet, Lower Canada. Claude Thibault, “The Gosford commission, 1835–1837, and the French Canadians” (ma thesis, Bishop’s Univ., Lennoxville, Que., 1963). Léon Pouliot, “Lord Gosford et Mgr Lartigue,” CHR, 46 (1965): 238–46.

Cite This Article

Phillip Buckner, “ACHESON, ARCHIBALD, 2nd Earl of GOSFORD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 27, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/acheson_archibald_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/acheson_archibald_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | Phillip Buckner |

| Title of Article: | ACHESON, ARCHIBALD, 2nd Earl of GOSFORD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | February 27, 2025 |