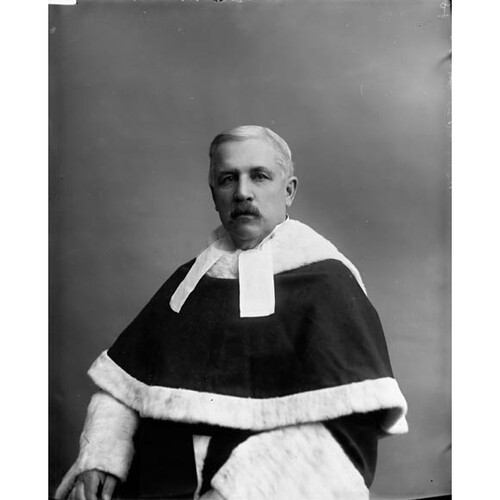

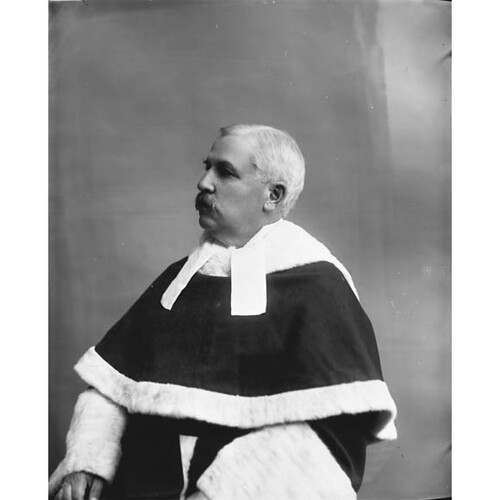

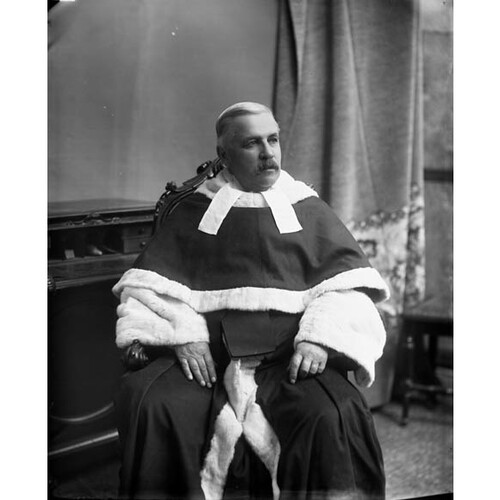

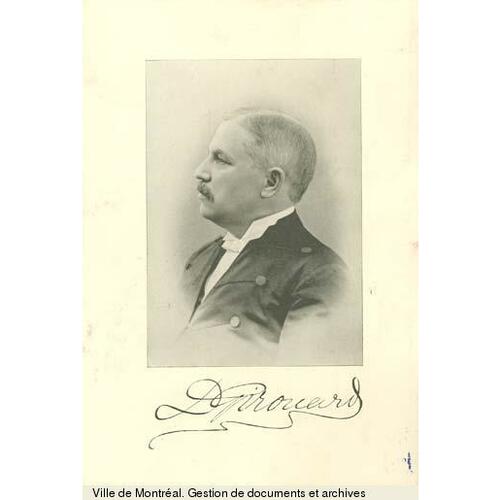

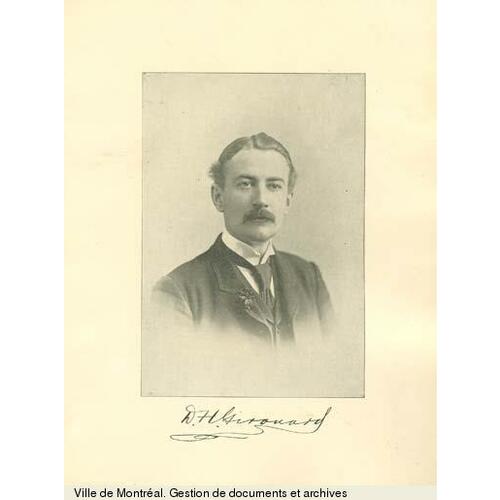

GIROUARD, DÉSIRÉ, lawyer, politician, judge, and author; b. 7 July 1836 in Saint-Timothée, Lower Canada, son of Jérémie Girouard, a farmer and wheelwright, and Hyppolite Picard; m. first 20 Jan. 1862, in Montreal, Marie-Mathilde Pratt, daughter of Jean-Baptiste Prat*, and they had one child; m. there secondly 6 Feb. 1865 Essie Cranwill, and they had six children; m. thirdly 6 Oct. 1881 Edith Bertha Beatty, and they had three children; d. 22 March 1911 in Ottawa.

Désiré Girouard attended a parish school in Saint-Timothée from 1844 to 1848 and the college of the Brothers of the Christian Schools in Beauharnois during 1848–50. From 1850 to 1857 he was enrolled at the Petit Séminaire de Montréal, where he was a prize-winning student. In 1857 he became a member of the literary circle of the Cabinet de Lecture Paroissial, which nurtured his deeply religious beliefs and contributed to his lifelong conservative views. He was an unabashed opponent of the radical Institut Canadien and his brazen appearance at its meeting of 18 March 1858, from which he was ejected, exacerbated tensions within that organization and contributed to the founding of the Institut Canadien-Français, where Girouard found more amenable intellectual surroundings.

In 1857 Girouard had entered Edward Carter’s law office and had begun the study of law at McGill College. He led his class for three consecutive years and gave the valedictory address on graduating in 1860. In 1874 he received the honorary degree of dcl and in 1880 he would be named a qc.

Before his admission to the bar in October 1860, Girouard had published an important legal text, Essai sur les lettres de change et les billets promissoires (Montréal). He would excel in commercial law, forming partnerships with leading Montreal lawyers which brought a steady stream of wealthy corporate clients during his 35 years in practice. His propensity to litigate ensured his presence in a variety of complex cases in which he had a personal interest.

In 1871 he founded in Montreal, with William Warren Hastings Kerr, Louis-Amable Jetté, John Adams Perkins, and Henri-Félix Rainville, La Revue critique de législation et de jurisprudence du Canada. Girouard’s contributions, such as “The Treaty of Washington,” which criticized the government of Sir John A. Macdonald* for failing to secure Canadian interests, frequently strayed into political issues. His articles on “Church and state” drew an immediate retort from Gonzalve Doutre*, president of the Institut Canadien, accusing him of using the journal for a “critical review of the Guibord trial [see Joseph Guibord*], still pending.”

During a judicial crisis in 1873–74 Girouard’s speech before the Montreal bar, detailing the longstanding grievances of its members concerning certain judges of the Court of Appeals and calling for a royal commission to inquire into the court’s affairs, set the stage for a boycott of the court which lasted the entire winter session. “The Bar is the guardian of the Bench,” he had reminded the audience. The stalemate was not resolved until several judges retired and the minister of justice, Antoine-Aimé Dorion*, became chief justice of the Court of Queen’s Bench in June 1874.

Girouard’s efforts to win federal elections in the 1870s involved strenuous campaigns fought amid charges of clerical intervention and corrupt electoral practices. A Conservative, he lost Jacques-Cartier in 1872 to Toussaint-Antoine-Rodolphe Laflamme*, his former law professor. As an independent, he lost Beauharnois in 1874. When Laflamme was nominated minister of inland revenue in 1876, Girouard’s decision to contest the required by-election in Jacques-Cartier was prompted by his involvement in legal suits over his rival’s dubious land dealings. He lost by 28 votes and contested the results up to the Supreme Court of Canada, which dismissed the case in 1878 when Laflamme was minister of justice. That same year Girouard lost again to Laflamme but the 12-vote deficit was changed to a 2-vote victory by a judicial recount even before the celebrated “Affaire de la Trappe” reached the courts. Although he was not personally involved in the affair, Laflamme was none the less disgraced when the story of his partisans’ tampering with a ballot-box by means of a trapdoor in a home in the parish of Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue came out during their trial. Girouard was undefeated in Jacques-Cartier for the next 17 years.

In the House of Commons Girouard introduced a number of private bills, including a measure to legalize marriage to a deceased wife’s sister. This bill, introduced in 1879, proved so controversial to conservative church authorities that he had to withdraw it. After considerable diplomacy, he secured passage of a modified version of the bill in 1882. A similar measure passed by the British House of Commons in 1850 was not made law until 1907. Girouard’s most notable speech came on 7 July 1885 when he spent over six hours defending the government’s handling of the Riel affair [see Louis Riel*]. He was sympathetic to the Métis’ grievances but did not believe they were of such magnitude “as to warrant their resorting to arms.” He concluded, however, with a plea for the government to “exercise its clemency in favour of the prisoners now confined at Regina.”

Viewing Riel’s trial as legally flawed and grossly unfair, Girouard became furious with Macdonald’s apparent willingness to allow the death sentence to stand. As the crisis deepened Girouard began to emphasize the question of Riel’s sanity as a means of avoiding his execution. He initiated a series of meetings among leading Quebec Conservatives to pressure the government into commuting the sentence. On 13 Nov. 1885, 16 Conservative members from Quebec signed a telegram to Macdonald calling the imminent execution of Riel “an act of cruelty” for which they would not take responsibility. When the minister of justice, Sir Alexander Campbell*, later published a defence of the government’s actions, Girouard responded on 7 Dec. 1885 with a widely printed open letter, in which he concluded that “history will perhaps say that Riel has been executed for a crime which he did not commit, and that we have been guilty of a judicial murder.” Girouard spent the months after Riel’s execution supporting Honoré Mercier*’s project of forming the Parti National, but his outrage with the Conservative government could not overcome his long-standing antipathy to the Liberals; he soon withdrew from the nationalists’ cause and rejoined the Conservatives. Yet when the issue of Riel came before the house in March 1886 he and 16 other Conservatives from Quebec, “the Bolters,” voted against their own government as a matter of conscience.

Girouard’s enthusiasm for partisan politics was considerably diminished by the Riel affair and he declined cabinet positions in 1891 and 1895, perhaps aware that the Conservative era in federal government was drawing to a close and that the party was no longer serving the best interests of French Canadians. In 1890 he was a leading member of the special parliamentary committee that investigated the conduct of Major-General Sir Frederick Dobson Middleton* in the North-West Territories and, as chairman of the committee on privileges and elections, he presided over the investigation into charges of corruption against Sir Hector-Louis Langevin* and Thomas McGreevy* in 1891, during which his impartial conduct was widely praised. He acted as counsel for Quebec in cases before the Supreme Court of Canada involving native claims under the Robinson treaties of 1850 [see William Benjamin Robinson*] and on 28 Sept. 1895 he accepted a judgeship in the court. Despite his lack of judicial experience, Girouard was favourably received since he brought to the court a reputation for political independence, honesty, and legal scholarship.

A keen genealogist and local historian, Girouard was the author of numerous historical pamphlets. Several of them formed the basis of a manuscript translated into English by his son Désiré Howard and published in Montreal in 1893 as Lake St. Louis, old and new, illustrated, and Cavelier de La Salle, Girouard’s main historical work. In recognition of his literary contributions he received the Confederation Medal from the Earl of Aberdeen [Hamilton-Gordon*] in 1895. He was proud of the fact that the first Girouard in Canada, Antoine (1696–1767), who had come to Montreal about 1718, had worked as secretary to Claude de Ramezay*, governor of Montreal. He found time to research his family’s origins in France and incorporated his findings into L’album de la famille Girouard, probably published in Montreal in 1906. In 1892 Girouard had become the first mayor of Dorval, where his spacious residence, Quatre Vents, provided an appropriate setting for his aristocratic demeanour.

Several times in 1910, in the absence of the governor general and the chief justice, Girouard, the senior puisne judge, acted as administrator of Canada. At the time his son Sir Édouard Percy Cranwill Girouard was governor of the East Africa Protectorate (Kenya) and newspapers were quick to point out that two French Canadians, father and son, were representing the king in two important possessions of the British empire. In September Girouard’s message of welcome to Vincenzo Cardinal Vannutelli, the pontifical legate attending the International Eucharistic Congress at Montreal, and the manner of his participation in the congress itself, became the object of a churlish press campaign by several Ontario newspapers, which took some of the lustre off the distinction of administrator and probably denied him the same title as his son.

On 6 March 1911 Désiré Girouard, already in failing health, was thrown from his sleigh on an Ottawa street; he died two weeks later. Funerals were held in Ottawa and Montreal and he was buried in the Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery, Montreal, on 24 March.

Désiré Girouard produced several books, as well as numerous pamphlets and articles on judicial matters, history, and genealogy. Several of his parliamentary speeches were also published. In addition to the works cited in the text, the following items are worth noting: Étude sur l’acte concernant la faillite, 1864 (Montreal, 1864); La famille Girouard, 1696–1884 ([Dorval, Qué., 1884]); and La question du canal de Beauharnois (Montreal, 1873). A partial list of his publications appears in P.-G. Roy, “Ouvrages publiés par feu l’honorable juge Désiré Girouard, de la Cour suprême du Canada,” BRH, 22 (1916): 257–58. A more extensive though not definitive listing is provided in the CIHM, Reg. Articles by Girouard were published in L’Écho du Cabinet de lecture paroissial (Montréal), 3 (1861), La Rev. critique de législation et de jurisprudence du Canada (Montréal), 1 (1871)–3 (1873), and BRH, 4 (1898)–12 (1906).

ANQ-M, CE1-51, 20 janv. 1862, 6 févr. 1865. NA, MG 30, E313. Gazette (Montreal), 5, 14 May 1860; 16–18 Dec. 1873; 8, 11 Nov. 1876. La Minerve, 24 juill. 1855; 17 juill. 1856; 23 juill. 1857; 31 mars, 24 avril 1858. Le Monde (Montréal), 9 déc. 1885. Montreal Herald, 17–18, 23 Dec. 1873, continued as Montreal Daily Herald, 24 March 1910. Le Pays (Montréal), 26 mars, 6, 13, 20 avril 1858. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). CPG, 1878–95. Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Québec, vols.1–9. J. G. Snell and Frederick Vaughan, The Supreme Court of Canada: history of the institution ([Toronto], 1985). Joseph Tassé, Le 38me fauteuil ou souvenirs parlementaires (Montréal, 1891).

Cite This Article

Michael Lawrence Smith, “GIROUARD, DÉSIRÉ,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 21, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/girouard_desire_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/girouard_desire_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michael Lawrence Smith |

| Title of Article: | GIROUARD, DÉSIRÉ |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | January 21, 2025 |