Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

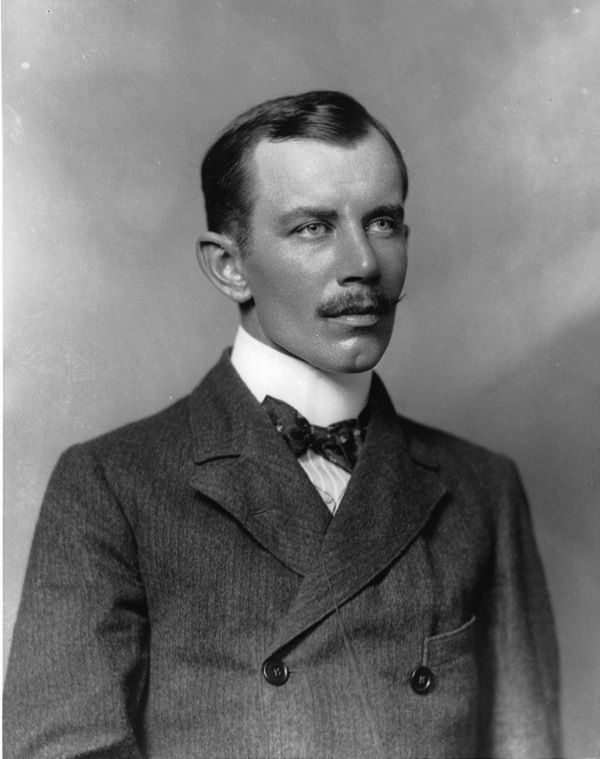

Girouard, Sir Édouard Percy Cranwill, military engineer, railway builder, colonial administrator, office holder, and industrialist; b. 26 Jan. 1867 in Montreal, son of lawyer Désiré Girouard* and Essie Cranwill; m. 10 Sept. 1903 Mary Gwendolen Solomon (d. 1916) in Pretoria (South Africa), and they had one son; they divorced in 1915; d. 26 Sept. 1932 in London, England.

During his childhood Édouard Percy Girouard lived in various homes in the fashionable part of Montreal that developed along Sherbrooke between Aylmer and Peel streets in the last quarter of the 19th century. Educated at home in a bilingual environment until age ten, he attended the Petit Séminaire de Montréal in 1877–78, but he did not complete the following academic year since his mother died in the spring of 1879. That fall Édouard Percy, an older sister, and a younger brother were sent to boarding schools; his father, who after a judicial recount was declared elected for the Conservatives in the federal riding of Jacques-Cartier, would spend most of his time in Ottawa. Édouard Percy attended the Séminaire de Saint-Joseph des Trois-Rivières. While his academic work improved from “well enough” to “excellent” over the next three years, his classmates would chiefly remember him as the resourceful “petit blond,” with his enthusiasm for geography and his temporary engineering works, created on the playground in the icy slush of spring.

In 1882 Girouard impulsively decided to become a soldier and set his sights on the Royal Military College (RMC) of Canada in Kingston, Ont., despite the fact that only three French Canadians had been accepted there since the college’s opening in 1876. Students who had not been educated in English found the entrance examinations extremely difficult. Girouard failed in his first attempt, but after his father pressured his friend and colleague Adolphe-Philippe Caron*, the minister of militia and defence, he was allowed to write a supplementary exam. Although his scores in mathematics were still deficient, he entered RMC as cadet 147 in the fall of 1882.

RMC had a strong engineering curriculum designed largely by its founding commander, Colonel Edward Osborne Hewett*, and implemented by Professor Robert Carr-Harris, who taught civil engineering from 1879 to 1897. The tiny permanent Canadian force could absorb just a few RMC cadets, and only four commissions in the regular British army were offered to them each year. Thus most graduates would find careers in the engineering and mining industries. Girouard’s academic skills steadily improved until he led his class in 1885–86, yet a commission in the Royal Engineers eluded him when he graduated in the spring. Having had a job the previous summer as a chainman with a survey crew on the Canadian Pacific Railway, he now became an engineering draftsman on the “Short Line,” the company’s link between Montreal and Saint John. He was based in Greenville, Maine, until 1888 and that summer he was finally successful in lobbying for one of the extra commissions that the Royal Engineers offered to past RMC graduates.

Girouard spent the next two years in the officers’ training course at the School of Military Engineering in Chatham, England, where his practical experience in railway building and rousing choruses from “Alouette” drew attention. He obtained special leave to pursue a scheme for the coastal defence of England that called for naval guns mounted on railway carriages to be shuffled around on existing lines; in April 1891 he outlined his plan in a lecture to the Royal United Services Institution in London, which later that year published his paper and the discussion that followed. Assigned as traffic manager of the Royal Arsenal Railway in July 1890, he supervised for five years all aspects of the system, albeit a rather small one, and immersed himself in a methodical study of the history of military railways. On 28 July 1891 he was commissioned lieutenant.

In 1895 Sir Horatio Herbert Kitchener, the British commander-in-chief of the Egyptian army, requested Girouard’s services, but the War Office had scheduled him for duty in Mauritius. When an expedition to capture Dongola in northern Sudan was announced in 1896 as the first step towards the retaking of the country lost by the British and the Egyptians in 1885, Girouard obtained permission to join Kitchener. He was put in charge of repairing and extending the railway for 203 miles up the Nile River, from Wadi Halfa towards Dongola. For his services Girouard was made a companion of the Distinguished Service Order. The following year his reputation as the leader of Kitchener’s “Band of Boys,” the group of able young officers gathered by their commander, was cemented when he managed, under difficult conditions, the rapid construction of the railway from Wadi Halfa to Abu Hamed, 235 miles southeast across the Nubian Desert. The route eliminated the need to navigate 500 miles and three of the Nile’s five cataracts that had proved so onerous for General Garnet Joseph Wolseley* and the Canadian voyageurs on their unsuccessful expedition to relieve Major-General Charles George Gordon in Khartoum in 1884–85.

Work on the desert railway continued, but the stress of the traffic going towards the Sudan began to show on Egyptian lines, so in 1898 Girouard was sent to improve the section near Luxor. His work came to the attention of Lord Cromer, the British governor of Egypt, who offered him the presidency of the Egyptian Railways Board with a mandate to reorganize the entire system and clear the congestion at Alexandria’s harbour. Girouard took up his post in Cairo in June with the temporary rank of major and introduced sweeping personnel changes; within a few months he had produced a program of railway and harbour works that would be faithfully adhered to for the next 20 years. He was therefore not present at the battle of Omdurman, near Khartoum, on 2 Sept. 1898, when Kitchener’s forces were victorious, in large part because of their ability to move men and supplies.

The following year Girouard became an imperial celebrity when two books on the Sudan campaign appeared. In The river war Winston Churchill, who had served in the British cavalry and acted as a war correspondent, painted a compelling sketch of the engineer “to whom everything was entrusted.” Girouard estimated every detail of the future railway in a thick notebook so that “the working parties were never delayed by the want even of a piece of brass wire.” Another British war correspondent, George Warrington Steevens, focused on Girouard’s colonial irreverence for authority in With Kitchener to Khartum. “He is credited with being the one man in the Egyptian army who is unaffectedly unafraid of the Sirdar [Kitchener].” Writing for an imperial audience, Steevens described Girouard as a blend of “French audacity of imagination, American ingenuity, and British doggedness in execution.” When Girouard visited Montreal in September 1899 Canadian military authorities, sensing the probability of a war with South Africa, were delighted to stage a banquet at the Windsor Hotel in honour of this French Canadian military hero.

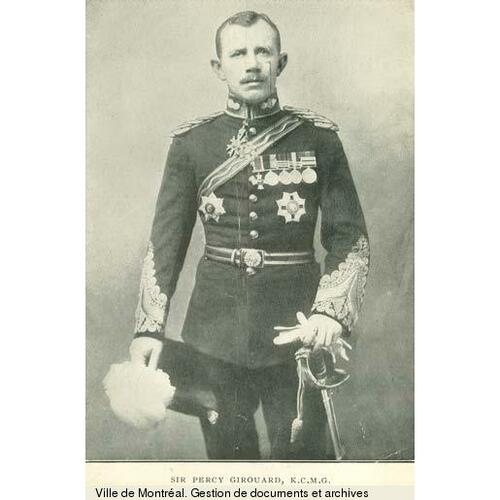

On his return to England in October 1899 Girouard made a case to the War Office that the Cape Colony railways were too complex to be taken over by the regular army during a campaign. As a result, he was named director of railways for the British force in South Africa. Now a captain and brevet major, he was given the local rank of lieutenant-colonel. His staff expanded to include RMC graduates Herbert Colborne Nanton and Henri-Gustave Joly de Lotbinière and several members of the “Band of Boys.” He achieved a delicate balance: the maintenance of civilian railway operations with the military requirements of transporting men and supplies from South African ports to the front. His rapid reconstruction of damaged lines and building of innovative low-level deviations around destroyed bridges permitted the swift movement of goods and personnel on the captured lines in the Orange River Colony and the Transvaal and ensured the speedy advance of Lord Roberts’s forces in 1900. During the frustrating days of guerrilla war after the conventional fighting was over, Girouard assumed the directorship of the Imperial Military Railways and was responsible for all South African lines except those in Natal. In April 1901 he was made a kcmg.

In 1902 Girouard was named commissioner of the Central South African Railways (CSAR). Working on the fringe of the “Kindergarten,” an informal club of young colonial administrators such as John Buchan who were recruited by the high commissioner, Lord Milner, for South Africa, Girouard developed ambitious plans for the CSAR: to replace ageing rolling stock, add several de luxe trains, and expand the permanent way. The following year he married 20-year-old Gwendolen Solomon, the only child of Sir Richard Prince Solomon, attorney general of the Transvaal and a key constitutional adviser to Lord Milner. His celebrity status was again confirmed when, in 1903, the Montreal Daily Herald ranked him seventh in a poll of Canada’s “Greatest Living Men,” but barely six months later his star fell. In 1904 an economic slump in the Transvaal halted plans for railway expansion, and the growing costs of railway administration came under determined attack from the Randlords, a network of capitalist mine owners in Johannesburg. A French-speaking colonial lacking the public-school background of many in Milner’s Kindergarten, and a holdover from the British military administration, Girouard was a likely target. Determined to protect the railway from the short-sighted interests of the mine owners, as he had protected its operations from interfering generals during the war, and confident that he had the support of Lord Milner, he failed to see that the political ground was shifting. His sometimes-cavalier approach to accounting methods and a prickly public defence sealed his fate. Milner, yielding to pressure, asked for his resignation. A somewhat humiliated Girouard returned to England where, after six months’ leave with pay, he settled down in London on the staff of Lord Methuen, head of the eastern command. Eighteen months later Girouard was appointed assistant quartermaster general to the western command based in Chester.

Girouard’s prospects improved when Churchill, the under-secretary of state for the colonies, facilitated his appointment to replace Sir Frederick John Dealtry Lugard as high commissioner of Northern Nigeria in February 1907 (his title was changed to governor in May 1908). Military security and the promise of cotton production in Britain’s most populous African colony necessitated a sound transportation system. Girouard was mandated to build the 366-mile Baro–Kano Railway to open ancient Hausaland to the Niger River. He implemented what would become known as policies of “indirect rule” (administration through native chiefs) even before Lugard had fully articulated them. Concerned that the railway would bring a flood of land speculators and undermine the native rights of a vast population, Girouard was instrumental in setting up the Northern Nigerian Lands Committee that met in London in 1908. The Land and Native Rights Proclamation of 1910, based on the committee’s report, embodied the main ideas that Girouard had pushed for, namely, that native rights to all the land and the produce thereof could not be alienated. Modern critics have argued that although Girouard’s policies strengthened traditional African authorities and prevented the establishment of private-land ownership, they were paternalistic and precluded the modernization of feudal structures, thus delaying the emergence of capitalism and the development of Northern Nigeria.

Girouard’s forceful personality and familiarity with railway and land-tenure questions made him the ideal candidate for the post of governor of British East Africa (Kenya), and his appointment was announced on 2 Aug. 1909. The completion in 1903 of the Uganda Railway from Mombasa on the Indian Ocean to Lake Victoria had brought social upheaval and a succession of governors who had been unable to reconcile the competing demands of European settlers, Asian immigrants, and indigenous populations. Girouard arrived in Nairobi in September 1909. Too late to undo a decade of settlement by whites, he was inclined, as a colonial himself, to consider carefully their grievances. His energy and personal charm initially produced great optimism among all sectors of the colony until a land problem erupted.

In 1904 a treaty with the nomadic Masai had divided the clans and given them two separate reserves, but the land-hungry settlers and the land-needy Masai continued to clash, especially on the fertile Laikipia plateau, north of the railway. Girouard favoured the consolidation of all Masai on one expanded reserve south of the railway and convinced the northern Masai clans to resettle. However, the Colonial Office suspected a land grab by the settlers and in April 1910 ordered Girouard to halt the move on the basis that the treaty of 1904 was being violated. Girouard clarified the situation during a visit to London in 1911. He then crafted a framework to reflect the political landscape and negotiated a new treaty with the Masai. The Colonial Office agreed to the expanded reserve but the move had to be delayed and the Masai suffered great hardship, while suspicions lingered in London about white settlers’ involvement in events. Girouard’s position became increasingly untenable as he lost the confidence of the secretary of state for the colonies, Lewis Harcourt, and he resigned abruptly from the colonial service and the army in July 1912. He then accepted an offer he had been mulling over for a year: to join the firm of Sir W. G. Armstrong, Whitworth and Company Limited, a major manufacturer of armaments, locomotives, ships, aircraft, and automobiles.

Girouard spent the next two years as the managing director of Armstrong’s massive works at Elswick in Newcastle upon Tyne, England. When the First World War broke out in 1914, Kitchener asked him to act as a consultant on railway matters on the Western Front. In April 1915 he resigned from Armstrong, Whitworth to avoid a conflict of interest and spend more time on problems of munitions and industrial labour supply for the War Office. When the Ministry of Munitions was formed in June 1915 he was named director general of munitions supply. He may have believed the newspaper articles that dubbed him the man of “push and go” that his minister, David Lloyd George, had sought. Girouard was a perfect exemplar of the pan-imperialist, as the Times (London) emphasized in reporting his speech to munitions workers on 12 June 1915. “Sir Percy Girouard … said he stood there as a British subject, a French-Canadian. For 250 years his forebears had resided in Canada.… They had enjoyed under the British flag, the Roman Catholic religion, the French language, and the old Napoleonic and pre-Napoleonic law without hindrance and with great tolerance. Was it any wonder then that French-Canadians … all felt what it would mean to them, to the Empire as a whole, and to the world if anything ever occurred to upset the equilibrium of liberty which the Empire represented.”

The ministry had been formed in response to the shell crisis of 1915, when it was realized that the government of Herbert Henry Asquith had failed to supply the necessary munitions to the Western Front. Lloyd George’s interest in dispersing contracts among new industrial entrepreneurs conflicted with Girouard’s view that the traditional armourers could be stimulated to attain higher production levels, which created intense friction between these two forceful personalities. A mere six weeks after the ministry was formed Girouard was forced out, and he returned to his work at Armstrong, Whitworth.

The post-war restructuring at the company led to battles in the boardroom and Girouard resigned abruptly in January 1920, only to reappear two months later. In 1922 he was promoted by a group of London businessmen, with the support of the Foreign Office and the Department of Overseas Trade, as the person to head the takeover of a vast concession of 50,000,000 acres, with mineral rights and tax benefits, that the Peruvian government offered in exchange for the construction of 1,864 miles of railway which would be carried out by Armstrong, Whitworth. Instead, an American syndicate, headed by Canadian Robert William Dunsmuir, secured the contract in 1923 and Girouard resigned from Armstrong, Whitworth.

Girouard’s personal life had been under great strain since 1910 as his marriage began to unravel. In 1914 his young wife petitioned for divorce on the grounds, certainly fabricated, of adultery. When the divorce was finalized in early 1915 she went to Egypt to marry Captain Robert William Oppenheim, whom she had come to know in British East Africa during Girouard’s governorship. When Oppenheim was deployed in the Gallipoli campaign she returned to England, and in 1916 she died giving birth to twins who did not survive. Girouard’s life became somewhat more orderly in 1922 when a niece, Virginia Cranwill Skynner, came to England from Winnipeg to keep house for him; the eight years they lived together at Holborough Cottage in Kent, where he was involved with Portland cement operations, were among the most peaceful of his life.

In 1930 and 1931 Girouard made two extended business trips to Colombia, South America, to consult on cement projects and railways; the voyages took a toll on his health. Prostate and urinary-tract problems were complicated by a ruptured appendix, which, despite surgery, led to his death on 26 Sept. 1932. Girouard was survived by a son, Richard Désiré Girouard; the British architectural historian and writer Mark Girouard is his grandson.

Girouard was a man of boundless energy, a master of detail, and a brilliant innovator who found it difficult to be constrained by authority and convention and who occasionally lost sight of significant political realities. Wherever he worked, however, he inspired deep loyalty in all who served with him, and the construction of 588 miles of the Sudan Military Railway, at the rate of one and one-sixth miles per day across the Nubian Desert, remains one of the most remarkable engineering achievements of the Victorian era.

Sir Édouard Percy Cranwill Girouard is the author of “The use of railways for coast and harbour defence,” Royal United Services Instit., Journal (London), 35 (1891): 631–44; History of the railways during the war in South Africa, 1899–1902 (London, 1903); “Railways in war,” Royal Engineers Journal (Chatham, Eng.), [new ser.], 2 (1905–6): 16–27; “The railways of Africa,” Scribner’s Magazine (New York), 39 (1906): 553–68; “Communication services,” Royal Engineers Journal, [new ser.], 3 (1906–7): 69–79; “The development of Northern Nigeria,” African Soc., Journal (London), 7 (1907–8): 331–37; “The Sudan Military Railways in 1896–1898,” in The story of the Cape to Cairo railway & river route from 1887 to 1922, comp. Leo Weinthal et al. (5v., London, [1923–26]), 2: 327–34.

LAC, R2396-3-0; R6169-0-4. National Arch. (G.B.), CO 446/57-CO 446/85; CO 533/62-CO 533/109. Private arch., Mark Girouard (London), who holds the corr. of Lady Girouard, as well as the following works by E. P. C. Girouard: “Duty and reflections in Africa” (notebook, n.d.), “Egypt and the Sudan” (typescript, n.d.), “The imperial ideal” (ms, n.d.); Mrs Virginia Robinson (Victoria), Corr. of Sir E. P. C. Girouard to V. C. Skynner, 1930–32. Tyne and Wear Arch. (Newcastle upon Tyne, Eng.), D.VA; DS.REN. “Sir Wilfrid, Strathcona, Sir Charles head the list of Canada’s greatest living men in voting contest,” Montreal Daily Herald, 7 Nov. 1903. Christopher Addison, Four and a half years: a personal diary from June 1914 to January 1919 (2v., London, [1934]); Politics from within, 1911–1918: including some records of a great national effort (2v., London, 1924). R. B. D. Blakeney, “K. and Gerry: railways in war time,” National Rev. (London), 106 (1935–36), no.636: 86–94. Mary Bull, “Indirect rule in Northern Nigeria, 1906–1911,” in Essays in imperial government presented to Margery Perham, ed. K. [E.] Robinson and Frederick Madden (Oxford, Eng., 1963). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). W. [L. S.] Churchill, The river war: an historical account of the reconquest of the Soudan, ed. F. [W.] Rhodes (2v., London, 1899). G.B., Ministry of Munitions, History of the Ministry of Munitions (12v., [London, 1922]). A. J. Kerry and W. A. McDill, The history of the Corps of Royal Canadian Engineers (2v., Ottawa, 1962–66), 1. A. H. M. Kirk-Greene, “Canada in Africa: Sir Percy Girouard, neglected colonial governor,” African Affairs (Oxford), 83 (1984): 207–39. G. H. Mungeam, British rule in Kenya, 1895–1912: the establishment of administration in the East Africa Protectorate (Oxford, 1966). R. A. Preston, Canada’s RMC: a history of the Royal Military College (Toronto, 1969). E. W. C. Sandes, The Royal Engineers in Egypt and the Sudan (Chatham, 1937). R. W. Shenton, The development of capitalism in Northern Nigeria (London, 1986). M. L. Smith, “Sir Percy Girouard: French Canadian proconsul in Africa, 1906–12” (ma thesis, McGill Univ., Montreal, 1989). Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell). G. W. Steevens, With Kitchener to Khartum (Edinburgh and London, 1898).

Cite This Article

Michael Lawrence Smith, “GIROUARD, Sir ÉDOUARD PERCY CRANWILL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 24, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/girouard_edouard_percy_cranwill_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/girouard_edouard_percy_cranwill_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michael Lawrence Smith |

| Title of Article: | GIROUARD, Sir ÉDOUARD PERCY CRANWILL |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2018 |

| Year of revision: | 2018 |

| Access Date: | December 24, 2025 |