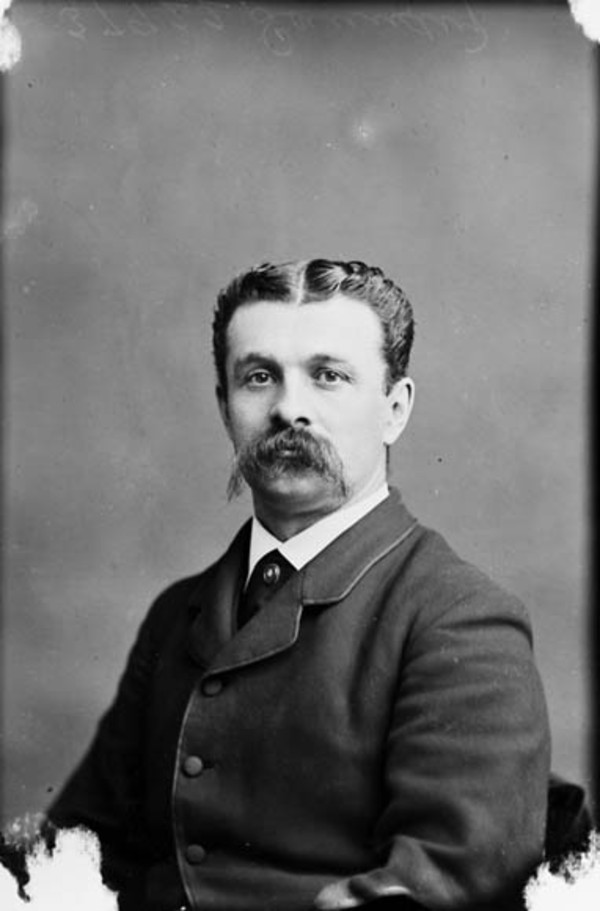

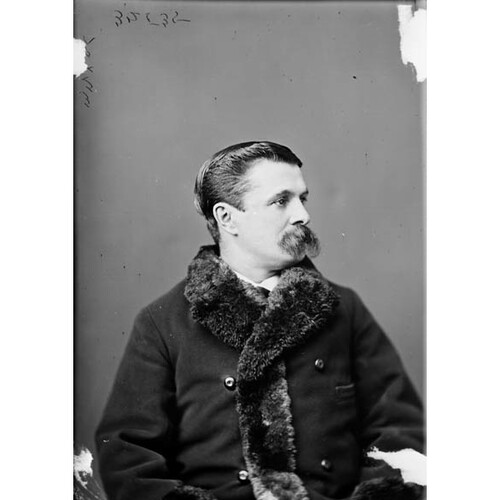

LANDRY, PHILIPPE (baptized Charles-Philippe-Auguste-Robert, he signed Philippe and sometimes Auguste-Charles-Philippe-Robert), agronomist, militia officer, and politician; b. 15 Jan. 1846 at Quebec, son of Jean-Étienne Landry*, a physician, and Caroline-Eulalie Lelièvre; m. first 6 Oct. 1868 Wilhelmine Couture in Saint-Gervais, Que., and they had six children; m. secondly 4 Nov. 1908, at Quebec, Amélie Dionne, the widow of lawyer Édouard Taschereau; d. there 20 Dec. 1919.

Of Acadian descent, Philippe Landry came from a devoutly Christian family who lived in Saint-Roch ward. In the autumn of 1855 his father enrolled him in the commercial program taught by the Brothers of the Christian Schools in the newly opened Collège de Lévis. After only two years he transferred to the Petit Séminaire de Québec, where he did his classical studies until 1866. Hot-headed by nature, in 1862 he enlisted in the Corps des Cadets de Québec, which was just being organized in the wake of the Trent affair [see Sir Charles Hastings Doyle*]. He volunteered to go and fight the Fenians in 1866. On 28 September he entered the school of agriculture at Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière (La Pocatière), where he completed a two-year course in one year. In addition, he found time to do a few demonstrations in chemistry for the students in the faculty of arts at the Université Laval and in 1867 to publish a pamphlet entitled Boissons alcooliques et leurs falsifications, which was the result of a study carried out at Laval under Professor François-Alexandre-Hubert La Rue*. He was also a member of the Entomological Society of Canada, founded in 1863.

Landry left the school of agriculture on 30 Sept. 1867, at the age of 21. Described as “short, robust, exuberant,” he was a fighter and had considerable talent for public speaking and writing. Like his father, he was a Conservative of the school of Sir George-Étienne Cartier*, but rather punctilious where honour, religion, or country were concerned. He was at home with the agriculturalist discourse of the Gazette des campagnes (Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière). In 1868 he moved to Saint-Pierre-de-la-Rivière-du-Sud and settled on a farm bought by his father from the archbishop of Quebec in May. He said that he farmed about 360 arpents and conducted various experiments. He was married in October and on 18 December received his captain’s commission in the 2nd Battalion of L’Islet county militia, which was renamed the 61st (Montmagny and L’Islet) Battalion of Infantry in April 1869. The following year he became a member of the new Société de Colonisation de Saint-Pierre de Montmagny.

Landry’s association with the Quebec élite and with high-ranking militia officers, and his involvement in the community, made him something of a local celebrity, but his appetite for action and combat made him dream of a wider stage. The opportunity arose in December 1873, when a by-election was held in the provincial riding of Montmagny. Landry ran against Liberal François Langelier, mounting an independent campaign focused on agriculture and the import of American butter. Defeated, he had his revenge in the general election of 7 July 1875. He may, however, have used illegal methods: clerical interference, and promises of hand-outs or jobs. In May 1876 the three judges of the Court of Revision – former Conservative Adolphe-Basile Routhier and two former Liberals, Vincislas-Paul-Wilfrid Dorion* and Marc-Aurèle Plamondon* – annulled the results in Montmagny and disqualified Landry from running for the Legislative Assembly for seven years. The decision, a split one, reeked of political revenge. His honour tainted, Landry published a vitriolic pamphlet entitled Où est la disgrâce? Réponse à une condamnation politique (Québec, 1876), which reminded Dorion and Plamondon: “Only yesterday you were pulling strings in elections.”

Dreaming of sweet revenge, Landry then divided his time between farming and politics. He and his father both joined the Cercle Catholique de Québec, founded on 26 May 1876 [see Jean-Étienne Landry]. With other Conservatives he battled against Wilfrid Laurier in Quebec East in November 1877 and in March 1878 he was amongst those denouncing Lieutenant Governor Luc Letellier* de Saint-Just’s so-called coup d’état. He won the seat for Montmagny in the September federal election. In addition, in 1878 he accepted the presidency of the Société d’Agriculture de Montmagny, an office he would hold until 1894 and again from 1897 to 1905. He also had published his Traité populaire d’agricultuie théorique et pratique (Montréal, 1878), which had won the gold medal in a competition organized by the provincial Council of Agriculture in 1873. He had been a member of that council himself since 1874.

At the age of 32 Landry finally had sufficient scope for his talent. During the first parliamentary session in March 1879, he made his mark as a formidable debater. Throughout his term as an mp (he would be re-elected in 1882), he spoke frequently in the House of Commons – more than 20 times each session – on such widely varied topics as railways, harbour construction, the Supreme Court, and the translation into French of federal government documents and militia regulations. He participated with the same enthusiasm in the political and religious battles of his day. As one of the owners of the Asile de Beauport from 1880, when his father had given him 25 per cent of the shares, he was a favourite target for the Liberals. Some maintained that government grants paid to its proprietors brought kickbacks of every kind to the Conservative party. Others claimed the asylum was so badly managed and the patients were so undernourished that a government take-over was in order. Landry reacted quickly to these insinuations and echoed the view of Bishop Louis-François Laflèche* that liberalism, Gallicanism, and freemasonry were at the root of all the political and religious difficulties in the province. In August 1883 he went to Rome to defend the honour of his father, whose title of professor emeritus had been withdrawn by the Université Laval, and on behalf of the Cercle Catholique to denounce a recent pastoral letter on secret societies issued by Archbishop Elzéar-Alexandre Taschereau*. In Rome he maintained that by directing his flock to reveal a Catholic’s masonic connections only to the priest who had jurisdiction, Taschereau was gagging politicians and journalists and playing into the hands of liberals. When Landry returned, he kept a close watch on the activities of Dom Joseph-Gauthier-Henri Smeulders, the apostolic commissary sent to Canada by Rome to investigate a number of questions. In December he circulated to the presbyteries a request that Dom Smeulders conduct an extensive canonical investigation into the activities of liberals. This circular touched off a heated controversy in the press.

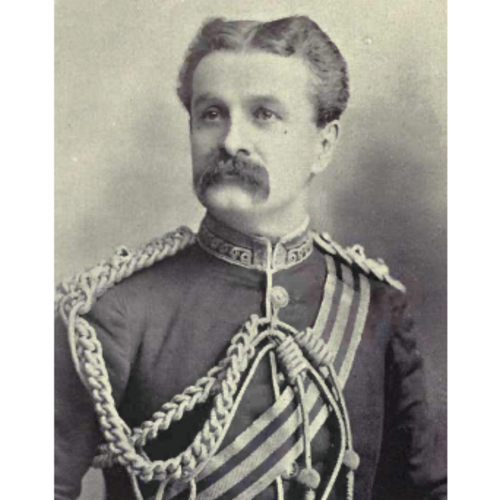

But politics has a bright side as well, and although he had been living at Quebec since 1883, on 9 Jan. 1885 Landry was named lieutenant-colonel of the 61st (Montmagny and L’Islet) Battalion. The title was largely honorary – all militia colonels were prominent politicians. At the end of March news of a bloody encounter between the North-West Mounted Police and the Métis [see Lief Newry Fitzroy Crozier*] put the amateur militia to the harsh test of reality. Landry was not called up, but the surrender of Louis Riel* in mid May posed a grave political problem. Landry hoped that Riel would be pardoned. After the Métis leader was hanged, Landry was given a seat on the Comité National de Québec, which had been formed to channel nationalist sentiment into a provincial political party; he was admitted to the group over the objections of his main Liberal opponent, Philippe-Auguste Choquette*. On 11 March 1886 he unexpectedly moved a resolution in the commons expressing regret that Riel had not been pardoned. His moderate speech set out four arguments: the jury’s composition gave no guarantee of impartiality; Riel was a monomaniac who was not entirely responsible for his actions; Major-General Sir Frederick Dobson Middleton* had treated him as a combatant; and civilized countries no longer imposed the death penalty for political offences. The motion was defeated by a vote of 146 to 52 and Landry lost some of his credibility. On the one hand, the Liberals suspected him of being in league with the Conservative ministers to present a motion doomed to defeat from the start but calculated to strengthen the government, and they bore a grudge against him. On the other hand, the ultramontanes attacked him for not having cut all ties with the “tory-masonic-Orange regime of Sir John [A. Macdonald*],” and with his own friend Sir Adolphe-Philippe Caron*, the minister of militia and defence. No longer involved with the nationalist movement, in the provincial election of October 1886 he campaigned with the Conservatives against Honoré Mercier* and threw all his energies behind Thomas Chase-Casgrain, the party’s candidate in the riding of Quebec. In the federal election of February 1887, pursued and harassed by Liberals and ultramontanes, Landry was defeated in Montmagny.

While Landry’s political life was in eclipse, his social life was not. On 25 Dec. 1888 he was appointed aide-de-camp extraordinary to the governors general of Canada. He had been living for several years at the Villa Mastaï in Beauport, and was often seen on important occasions as a member of the platform party. Behind the scenes, he continued to devote himself to high political strategy. He was on intimate terms with Lieutenant Governor Auguste-Réal Angers, whom he served as private secretary for a time. According to the Liberals, he was the backer who helped Angers live on the scale of a grand seigneur. With others, on 13 Jan. 1892 he launched the Conservative newspaper Le Matin to serve as a counterweight in the Quebec region to the Liberal L’Électeur [see Ernest Pacaud*]. The publisher was Louis-Philippe Pelletier* and the editor-inchief Eugène Rouillard*, formerly of Le Nouvelliste (Québec). Landry, who helped finance the enterprise, and Jules-Paul Tardivel* would be occasional contributors. All this dedication to the Conservative party, together with the support of Angers, earned Landry a seat in the Senate on 23 Feb. 1892.

The appointment marked a turning-point in Landry’s personal life. The sale of the Asile de Beauport to the Sœurs de la Charité de Québec, ratified by a statute passed on 8 Jan. 1894, consolidated his financial situation. Landry was to receive an annual income of $5,218.84 over the next 60 years. This sum, along with the approximately $100,000 he had inherited from his father in 1884 and various other properties and sources of income, made him a wealthy man who was in a position to indulge his taste for controversy and struggle as well as his innate need to be active. He remained interested in farming, however, and in 1892 helped found the provincial Syndicat des Cultivateurs. He became the president and manager of the Quebec Exposition Company, which was formed in 1892 “for the purpose of encouraging industry, the arts, and science in general.” In 1896 he was president of the province’s Council of Agriculture. He served as mayor of Limoilou from 20 Jan. 1896 to 4 Sept. 1900 and manager of the Compagnie Canadienne d’Acétylène at Lévis in 1901.

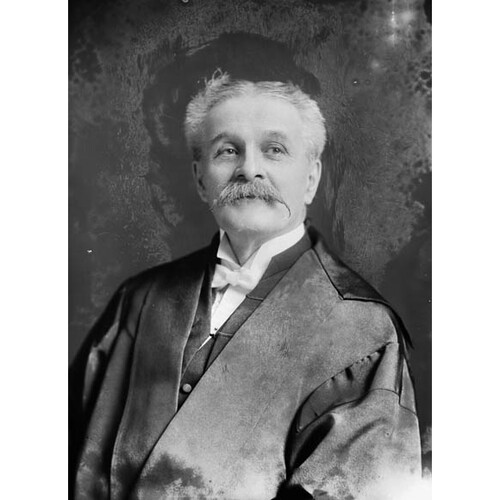

Politics, however, absorbed most of Landry’s energy. Well served by his memory and his “little papers,” he proved one of the most active senators. On 29 Feb. 1892 he had delivered his maiden speech in French in order to “affirm a principle and establish a right.” During this period, when Canadians were experiencing a serious identity crisis, Landry was on the firing line in every clash between differing perceptions of the country. In 1895 he supported remedial legislation restoring Catholics’ educational rights in Manitoba, and in 1897 he judged the Laurier–Greenway settlement of the problem [see Thomas Greenway*] unsatisfactory. In December 1899 he denounced the form of imperialism that threatened to destroy Canada’s autonomy in relation to Great Britain. In May 1902, with a number of other Quebec City Conservatives, he bought L’Événement [see Louis-Joseph Demers*] to make it a voice for the interests of the Quebec region, French Canadians, and the Conservative party. The paper suffered a defeat in its campaign for a transcontinental railway that would have its terminus at Quebec, and in 1904 it failed to prevent the Liberals from being returned to power at Quebec and in Ottawa.

The bills creating the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan in 1905, which threatened the status of French Catholic schools in the west, reopened the debate on national identity and put Landry in a difficult position. Caught between duty and party loyalty, he increasingly hedged. On 17 September he spoke from the same platform as Armand La Vergne* and Henri Bourassa* at a rally in Montmagny in support of French Catholic schools in the west. Landry flirted with the Nationalistes: he supported La Vergne’s campaign to extend the use of French in 1907 and Bourassa’s entry onto the provincial political scene in 1908. The hour for dramatic choices was drawing near, precipitated by the bill to establish a Canadian navy that Laurier introduced in the commons in January 1910. In April, unable to change the views of their leader, Robert Laird Borden, on Canada’s role within the British empire or on the question of Canadian identity, Landry and his friends considered forming a French Canadian party under Frederick Debartzch Monk. The idea made some headway, but because of disagreements about the navy and reciprocity, it ended in a hybrid alliance between the Conservative party and the Nationalistes in August 1911. The combination helped to defeat Laurier in the 1911 general election and Borden became prime minister.

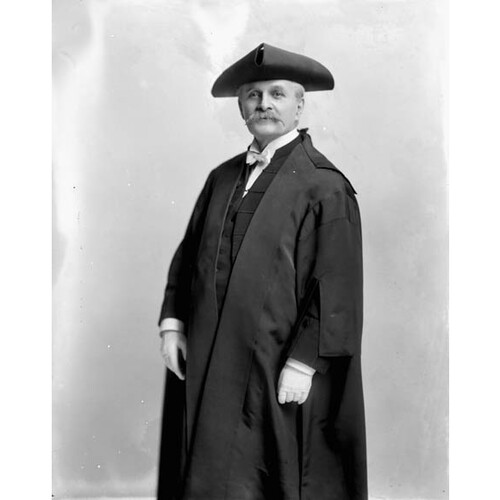

Borden did his best to divide the spoils of victory. On 29 October Landry was appointed speaker of the Senate. What more could he hope for than the golden retirement such a position promised? Once they were in power, however, the artificial unity of Nationalistes and Tories fell apart. Old antagonisms were rekindled by the Keewatin school question in March 1912 [see Borden], by Regulation 17 [see Sir James Pliny Whitney] in June, which limited the teaching of French in Franco-Ontarian schools, and by the naval question, which led in October to Monk’s resignation as minister of public works. Unable to “bow before triumphant fanaticism,” Landry drew his sword once more. He supported Monk and the cause of French schools. He urged Borden to get Regulation 17 disallowed and thus avoid the danger “to which the opponents of the French language are exposing confederation itself.” Borden referred him to the minister of justice, holding that disallowance was a matter for him. In December Landry dissociated himself from L’Événement, which was now being financed by the Forget family and toning down its nationalist stance. In May 1913, to avoid putting the government in an awkward position, he did not raise objections in the Senate to the Naval Aid Bill which had just been passed by the House of Commons; the issue seemed less urgent than that of French schools. On several occasions he considered resigning as speaker of the Senate, but his friends persuaded him to stay on. He himself seemed hesitant to break his ties with his party.

Far from healing internal divisions, Canada’s participation in World War I only exacerbated them. Franco-Ontarians, who were openly resisting educational directives from the province, were looked on as rebels paralysing the war effort. Since March 1913 they had had a newspaper to voice their opinions, Le Droit (Ottawa), but they did not have a leader. In April 1915 they found one in the person of Senator Landry, who agreed to serve as president of the Association Canadienne-Française d’Éducation d’Ontario. His gesture was noble and selfless. Landry wanted to defend “in the face of all opposition, a truly national cause” and, as he wrote to Archbishop Charles-Hugues Gauthier* of Ottawa, “to be an instrument of peace and conciliation in the hands of Providence.” In his view, what was at stake in the debate was the continued existence of separate schools, which alone could guarantee a French and truly Catholic education. He advocated a two-part strategy: on the one hand, to arouse public opinion and mobilize activists; on the other hand, to reach an amicable compromise through a discreet approach to politicians and religious leaders. The appeal to public opinion was successful, but the secret negotiations failed. Rome showed no urgent desire to declare itself on the matter, Borden refused to disallow the Ontario regulation, the Irish bishops went along with the educational directives, and Thomas Chapais* and other Conservatives deplored the strong tone of Landry’s letters to the secretariat of state at the Vatican. The situation of the Franco-Ontarian schools continued to deteriorate and the question was taking on the aspect of an ethnic confrontation. The courts nonsuited the Franco-Ontarians. Landry would not admit defeat. On 22 May 1916, following a tour of Quebec and French-speaking communities in Ontario, during which 600,000 signatures were collected on a petition calling for the disallowance of Regulation 17, he resigned as speaker of the Senate and severed his connections with the Conservative party. Landry’s resignation was a protest against the doctrine of federal non-intervention and a way of gaining more room to manœuvre. This striking move had a considerable impact. He was seen as a leader of French Canada and rallied both Bleus and Rouges to his standard. In June he accompanied Senator Napoléon-Antoine Belcourt* on his mission to plead the school question before the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London. Soon after his return on 19 August he was to learn some disappointing news. In a letter of 8 Sept. 1916 to Louis-Nazaire Cardinal Bégin*, Pope Benedict XV called for a compromise and left it to the episcopate to find one, but he recognized the right of Franco-Ontarians to a Catholic and French education. On 2 November the Privy Council decision upheld the legality of Regulation 17, but invalidated the formation of the “small school board” established by the Ontario government to run the separate schools in Ottawa [see Samuel Genest*]. Even these partial victories fuelled Landry’s zeal. He changed his strategy and began publicizing his submissions to political and religious authorities. He wrote more letters and memos, held more rallies, issued more threats. He also opposed conscription, held up the frightening prospect of a possible breakup of confederation, and attempted during the election of 1917 to organize a coalition of Liberals and Nationalistes.

Senator Landry’s struggle bore the marks of a gallant last stand. The Ontario government remained inflexible, but he was exhausting his strength. He was now fighting for every inch of ground, not against the Orange order, but against death. The illness that kept him bedridden did not stop him from drawing up new plans. According to obituaries, he died in action, like a soldier, patriot, and Christian, at Quebec on 20 Dec. 1919, aged 73. His passing was mourned throughout French Canada.

A listing of the pamphlets written by Philippe Landry is available in CIHM, Reg.

AC, Québec, État civil, Catholiques, Notre-Dame de Québec, 4 nov. 1908, 23 déc. 1919. ANQ-Q, CE1-22, 16 janv. 1846; CE2-17, 6 oct. 1868; CN1-255, 4 mai 1868. Arch. de la Ville de Québec, M1-2, conseil de ville, procès-verbaux, 10 avril 1893–26 mai 1900, 4 juin 1900–6 mai 1907. Arch. du Collège de Lévis, Qué., Fichier des anciens. ASQ, Fichier des anciens; Journal du séminaire, 2: 69. NA, MG 26, G: 110707–9, 195075–77, 195080–81; MG 27, II, E4. L’Action catholique (Québec), 20 déc. 1919. Le Devoir, 20, 22 déc. 1919. Le Droit (Ottawa), 20 déc. 1919. L’Électeur (Québec), 5 déc. 1893. L’Événement, 25 mai 1870, 2 juin 1876, 5 déc. 1899, 1er mars 1903. Gazette des campagnes (Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière [La Pocatière], Qué.), 14 janv. 1870, 31 déc. 1873. Le Matin (Québec), 13 janv.–19 sept. 1892. La Presse, 20 déc. 1919. Le Soleil, 22–23 déc. 1919. Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1880, 1883–86; Senate, Debates, 1892, 1894, 1897–1918. Canadian album (Cochrane and Hopkins). Le cinquantenaire de l’école d’agriculture de Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière (Québec, 1910). P. [E.] Crunican, Priests and politicians: Manitoba schools and the election of 1896 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1974). Directory, Quebec, 1867–1907. Patrice Gallant, “Généalogie du sénateur Philippe Landry, surnommé le grand-père des petits Franco-Ontariens,” Soc. Généal. Canadienne-Française, Mémoires (Montréal), 6 (1954–55): 33–39. J. Hamelin et al., La presse québécoise. Jules Landry, Le docteur J. E. Landry; conférence présentée . . . à la Société historique de Québec et à la Société canadienne d’histoire de la médecine ([Québec], 1965). J.-A. Lavoie, Le régiment de Montmagny de 1869 à 1931 (s.l., s.d.). Wilfrid Lebon, Histoire du collège de Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière (2v., Québec, 1948–49). Qué., Statuts, 1892, c.74; 1893, c.9; 1894, c.8. Élias Roy, Le collège de Lévis; esquisse historique (Lévis, 1953). Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Québec, vols.1–15. Philippe Sylvain, “Jean-Étienne Landry [1815–1884], l’un des fondateurs de la faculté de médecine de l’université Laval,” Cahiers de Dix, 40 (1975): 161–96.

Cite This Article

Michèle Brassard and Jean Hamelin, “LANDRY, PHILIPPE (baptized Charles-Philippe-Auguste-Robert) (Auguste-Charles-Philippe-Robert),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 1, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/landry_philippe_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/landry_philippe_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michèle Brassard and Jean Hamelin |

| Title of Article: | LANDRY, PHILIPPE (baptized Charles-Philippe-Auguste-Robert) (Auguste-Charles-Philippe-Robert) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | April 1, 2025 |