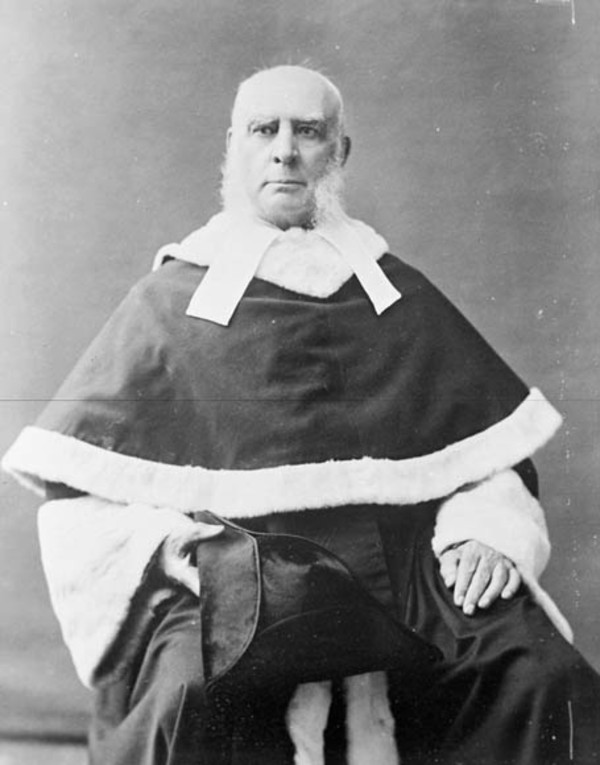

STRONG, Sir SAMUEL HENRY, lawyer and judge; b. 13 Aug. 1825 in Poole, Dorset, England, son of Samuel Spratt Strong and Jane Elizabeth Gosse, sister of Philip Henry Gosse*; m. 1850 Elizabeth Charlotte Cane, and they had two daughters; d. 31 Aug. 1909 in Ottawa.

In 1836 Samuel Henry Strong immigrated to the Canadas with his family. His father, who was ordained an Anglican priest the following year, became curate in Kingston, then chaplain of the forces at Quebec City, and, from 1837, rector in Hull and Bytown (Ottawa). Samuel studied at the Quebec High School and under private tutors before entering the office of Bytown lawyer Augustus Keefer, whose training provided the foundations for Strong’s distinguished legal career. The Canadian Law Times later reported that, in his early years in Bytown, Strong “on several occasions” associated with the Shiners [see Peter Aylen*] and that he joined the Orange lodge, becoming a master and “taking an active part in the . . . ‘Stoney Monday’” confrontations of 17 Sept. 1849 over the Rebellion Losses Bill [see James Bruce*].

Strong, like other aspiring students-at-law of his generation, kept term at Osgoode Hall in Toronto in order to participate in the required program of the Law Society of Upper Canada, and to attend court so as to learn from direct observation points of law and procedure. Later accounts speak of his days being “passed in study and retirement, the young student of law not making many friends.” An altercation with an “overbearing” police officer led to blows and an appearance in police court, where Strong “gave the first evidence of the marvellous power of arranging facts and presenting an argument for which he was afterwards so famous.” His “brilliant defence” led to the dismissal of charges against him; the constable, who had been the subject of previous complaints, lost his position.

Strong’s formal entry into the profession coincided with judicial reforms that saw the creation of a nine-member Court of Error and Appeal and the reorganization of the Court of Chancery, where his professional reputation would be made. Called to the bar in Hilary term 1849, he was elected a bencher of the law society in 1860 and was made a qc three years later. In 1858 he was appointed a lecturer in equity at Osgoode Hall. In Toronto he practised initially with Henry Eccles*. Others with whom he would be associated in practice included Thomas Wardlaw Taylor*, later a chief justice of Manitoba, James David Edgar*, and John Hoskin. Under the name of Strong and Matheson, he also worked in partnership with William Marshall Matheson.

During the first decade and a half of Strong’s career, his work was centred in the Court of Chancery, where he was often opposing counsel to Edward Blake*. Once his practice and reputation were well established, he took on responsibilities related to the reform and administration of law. He served from 20 Dec. 1856 to 5 Dec. 1859 as a commissioner for revising and consolidating the general statutes of Upper Canada. This activity not only strengthened his familiarity with the statutory framework of the jurisdiction, but also provided a practical introduction to the processes of drafting and revision, which he would again participate in at later stages of his career.

Strong’s characteristic impatience was evident when, for instance, he journeyed to Manitoulin Island in 1867 to investigate a series of charges, including mistreatment of the native population and assault, brought by the Reverend Jabez W. Sims against Charles T. Dupont, the local Indian affairs superintendent. He completed the inquiry in haste, the result of his desire “to put an end to a discussion which was consuming time uselessly, and which involved irritating recriminations.” Disturbed by the lack of opportunity Strong afforded him to reply to charges which Strong appeared initially to downplay, Dupont protested the tone of his report. He dismissed Strong as “manifestly, utterly and entirely ignorant of the Indian character.”

The year following this investigation, Strong, as a friend and legal adviser of Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald*, assumed responsibility for developing the earliest legislative proposal for the creation of a supreme court. Wrestling with the assignment during the winter of 1868–69, he reported to Macdonald that the task was “much more difficult work than I expected.” In particular, he expressed doubts about finding enough for the new institution to do under the exercise of original jurisdiction, and he urged the prime minister to modify his earlier objections against a grant of admiralty jurisdiction. Macdonald’s first bill for the establishment of the court, introduced in the House of Commons on 21 May 1869, would have conferred upon it an exclusive original jurisdiction with respect to important constitutional matters, including “all cases in which the constitutionality of any Act of the Legislature of any Province of the Dominion shall come in question,” in addition to appellate jurisdiction over civil and criminal matters arising in Canada. Exclusive jurisdiction in various admiralty matters was proposed, and the court, for the purpose of fulfilling its original jurisdiction, was to hold special terms twice annually in Toronto, Quebec, Halifax, and Fredericton. The bill, of which there was no second reading, attracted criticism for its centralist tendencies, which led Macdonald in 1870 to offer the assurance that it had been prepared “rather more for the purpose of suggestion and consideration, than for a final measure which Government hoped to become law.”

For his various efforts on behalf of Macdonald’s administration, and certainly not without regard for his formidable legal talent, Strong was named vice-chancellor of Ontario on 27 Dec. 1869. In his mid forties at the time of this first court appointment, Strong had devoted his entire adult life to the legal profession. But a lack of outside business experience was hardly evident in certain of his judgements then or later in his judicial career, for he was entirely willing to voice firm opinions as to the practical and commercial consequences of legal determinations in which he participated. For example, in one of his early decisions as vice-chancellor, Ontario Salt Co. v. Merchants Salt Co. (1871), he considered a challenge on grounds of public policy to an arrangement designed to establish a combine to control the production and sale of salt. In rejecting all arguments against the alleged monopoly, he spoke of the “manifest benefit and profit to the community” that resulted from such transactions, of the “inconvenience in trade” that a prohibition would produce, and of the support of “all public and scientific opinion” for his conclusions.

Continuing his involvement in reform, Strong accepted a provincial appointment in 1871 to serve along with James Robert Gowan, John Wellington Gwynne, and other judges on a commission of inquiry into the fusion of common law and equity. The inquiry achieved little, however, for it was dissolved in September 1872 by Edward Blake’s administration, which wanted to take immediate action on fusion. Strong returned to chancery and within two years moved on to higher judicial office: on 27 May 1874 he was appointed justice of the Ontario Court of Error and Appeal, where he was sworn in on 17 June. He served only briefly, because on 8 Oct. 1875 the federal Liberal administration of Alexander Mackenzie* named him to the new Supreme Court of Canada, along with William Buell Richards* of Ontario, William Johnston Ritchie* of New Brunswick, William Alexander Henry* of Nova Scotia, and Télesphore Fournier* and Jean-Thomas Taschereau* of Quebec.

Before the appointments were made, the Canada Law Journal discussed the candidates, noting with regard to Strong that he was “one of the best civil law jurists in Canada, and thoroughly familiar with the French language,” significant advantages in a nominee for the new bench. And candidate he was as far as the government was concerned, for he was thought to be “extremely anxious” to go to Ottawa, had been politically active, and appeared from his association with Macdonald’s supreme-court plan to subscribe to a centralist understanding of the British North America Act. But if presumptions about his centralist preference indeed figured in his appointment, the performance in constitutional cases of the new court’s youngest member might well have been surprising.

The general issue of provincial rights came before the court repeatedly until provincial sovereignty was formally accepted in 1892 by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, in the Maritime Bank case. Strong declined to associate himself with court colleagues who, at an early stage, as historian Paul Romney has described their position, “declared war on provincial rights” and “revealed themselves as totally committed to the centralist position.” In Lenoir v. Ritchie (1879), a case concerning the authority of provincial lieutenant governors to confer the designation of queen’s counsel, Strong rebuked fellow justices Henry, John Wellington Gwynne, and Henri-Elzéar Taschereau* for even addressing the constitutional question when, in his opinion, it was not essential to the decision of the case. Again, in Mercer v. Attorney General for Ontario (1881) [see Andrew Mercer*], Strong, together with Chief Justice Ritchie, dissented from the centralist interpretation of the majority in an escheats case that was successfully appealed by Ontario to the JCPC.

In contrast, in St. Catharines Milling and Lumber Co. v. the Queen (1887), a jurisdictional dispute involving a challenge by Ontario to the federal government’s authority to issue timber licences on Indian lands in northern Ontario, Strong presented a firm and principled dissent from the court’s finding for the province. His judgement is noteworthy for its forceful constitutional arguments in support of the dominion’s claim to jurisdiction as a result of treaty surrender. In his interpretation of the section of the BNA Act that dealt with “lands reserved for the Indians,” he insisted upon the importance of “recourse to external aids derived from the surrounding circumstances and the history of the subject matter dealt with.” He specifically affirmed the continuing force of the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which established native titles and imposed procedural requirements for the surrender of native lands. Having regard to the historical practice of recognizing that native title could be surrendered only to the crown, he went so far as to assert that even “if there had been an entire absence of any written legislative act ordaining this rule as an express positive law, we ought . . . to hold that it nevertheless existed as a rule of the unwritten common law, which the courts were bound to enforce as such, and consequently . . . these territorial rights of the Indians were strictly legal rights which had to be taken into account and dealt with in that distribution of property and proprietary rights made upon confederation between the federal and provincial governments.” Strong’s judgement is now better known for advancing the concept of usufructuary rights, which the JCPC, in its confirmation of the Supreme Court decision, employed to describe what it considered to be the subordinate and limited nature of native interests in land.

Throughout the 1890s controversial cases affecting minorities and provincial rights continued to come before the Supreme Court. Questions relating to the educational rights of religious minorities under section 93 of the BNA Act arose out of the Manitoba school situation. In Barrett v. the City of Winnipeg (1891), the court recognized the prejudice to the Roman Catholic and Franco-Manitoban community in the province’s Public Schools Act of 1890 and struck it down [see Thomas Greenway]. Here Strong, concurring with Chief Justice Ritchie, was part of a unanimous decision, which was reversed by the JCPC in 1892. Yet in a few years Strong, who became chief justice on 13 Dec. 1892 and was knighted on 26 June 1893, was part of a majority of three to two in a reference decision, the Brophy case of 1894, that denied to Manitoba’s Catholic community a right of appeal to the federal cabinet and declared parliament to be without authority to pass remedial legislation. Strong’s “narrow technical construction” in this decision, which the JCPC overturned in 1895, emphasized the authority of a legislative body to repeal its own enactments. His judgement has been explained by legal historian Gordon Bale as a consequence of his close association with members of the federal Conservative party and his desire to save the government from the divisive dilemma of remedial legislation.

The contentious subject of provincial legislation prohibiting the liquor trade came before the court in 1895 in the form of litigation and as a reference on a local-option amendment by the government of Sir Oliver Mowat to the Ontario statute on regulation. Strong characteristically delivered his more elaborate opinion in the former, reserving only a few lines for a dissenting comment in the reference proceedings, which found against local option. (The decision would be reversed by the JCPC in 1896.) To a greater extent than several of his colleagues, Strong arrived at judgements that accommodated provincial aspirations. In the liquor reference he construed the municipal powers specified in the BNA Act broadly, as an area exempt from federal control. Strong also appeared more willing than many of the other justices to accept concurrency: “There are in the Dominion and the provinces respectively several and distinct powers authorizing each, within its own sphere, to enact the same legislation on this subject of prohibitory liquor laws restraining sale by retail.”

By the mid 1890s numerous variations on liquor legislation had come before the court in the form of challenges to both federal and provincial schemes to regulate, tax, or prohibit the trade at the wholesale and retail levels. Strong, through his experience as an appeal judge as well as on the Supreme Court, had seen his fair share. He consistently – and often in dissent – formulated interpretations of specific provincial powers that would have preserved some scope for them against a potentially expansive federal trade and commerce authority under section 91 of the BNA Act. Yet his discussion of the issues, immediately before the provincial triumph at the JCPC in 1896, has been described by legal authority R. C. B. Risk as “short and flat, as though he had little interest in re-thinking prohibition or the usefulness of the distinction between retail and wholesale.”

Contemporary assessments of Strong’s legal skills and analytical capability were extremely positive. The Cyclopædia of Canadian biography (1886) regarded “his memory for judicial decisions” as “almost miraculous.” In its obituary the Canadian Law Times believed him to have been “specially distinguished for his knowledge of law as a science and of the principles of jurisprudence generally.” Whatever his intellectual merits, Strong’s performance on the bench does not suggest a high level of organizational capability. For his tendency to offer short, oral judgements not properly followed up with an elaboration of reasons, he has been accused by court historians James G. Snell and Frederick Vaughan of being “intellectually lazy and frequently irresponsible.” His lack of responsiveness to deadlines occasionally held up publication of court reports and he was known to lose or misplace judgements.

In the course of his nearly 30 years on the Supreme Court, Strong, largely because of illness, was absent from the bench for extended periods, including significant stretches during his service as chief justice. These absences, along with what were generously described as “his eccentricities,” helped to undermine his leadership of a court that made little progress towards achieving its promise or fulfilling the aspirations of its supporters. As chief justice, Strong failed, as had his predecessors, to infuse the institution with a clear sense of purpose.

Newspaper reaction to Strong’s appointment in 1892 had been favourable. The Toronto Daily Mail described the selection of the senior of the two remaining members of the original court (Fournier was the other justice) as a “foregone conclusion.” For its part the Ottawa Citizen expected the bar to conclude with it that Strong’s elevation was “the best appointment that could have been made.” This view was sadly mistaken. Indeed, evidence of the dissatisfaction that was later to emerge could already be found in the legal periodicals and in the lukewarm welcome Strong received from both the Canadian Law Times and the Canada Law Journal. The former, though willing to praise Strong’s experience and extensive knowledge, noted that “it seems unfortunately to be developing into a usage, easy to establish and difficult to break through, to make appointments by seniority.” The Canada Law Journal even restated a previously expressed preference for an outside appointment, such as Sir John Sparrow David Thompson*, justice minister in the administration of Sir John Joseph Caldwell Abbott*, to enhance the credibility of the Supreme Court. The appointment of a chief justice had in fact been briefly delayed by the ill health of Abbott and Thompson’s genuine interest in assuming the position. When Abbott was forced to resign, Thompson agreed to replace him and, against the advice of former judge, now senator, J. R. Gowan, who expressed reservations about the senior judge’s continued fitness for the post, he promoted Strong to the country’s senior judicial office.

Strong’s opinionated criticisms of his colleagues, outbursts of temper, and discourteous treatment of counsel now became a subject of wider public commentary and concern. In a letter to Macdonald in 1880, Strong had described justice Henry’s deliverances as “long, windy, incoherent masses of verbiage, interspersed with ungrammatical expressions, slang and the eeriest legal platitudes inappropriately applied,” and advised that “nothing but his removal from it can save the unfortunate Court.” By the mid 1890s relations between Strong and Gwynne were strained, with the chief justice complaining bitterly to the minister of justice about his colleague’s “senile irritability” and disinclination to attend judges’ conferences. Strong went so far as to threaten resignation: “If he will not or cannot be made to give way I am afraid I must.” Though observations such as these and the history of abusive remarks made to lawyers appearing before him provoked discussions about retirement and replacement, Strong continued to occupy the position of chief justice until 18 Nov. 1902, when he stepped down to serve as head of a royal commission for the revision and consolidation of Canadian statutes.

In 1897, while chief justice, Strong had become the first Canadian judge to sit on the JCPC, following its decision of two years before to secure the participation of senior justices from the courts of the British empire. Appointed in January, he was sworn in on 7 July. His earlier attitude to the committee had not been entirely favourable. During the course of argument in 1885 in the reference of the McCarthy Act (the dominion’s liquor-licensing act), Strong rejected the request of counsel that the Supreme Court break with practice and its standing rules to give reasons for the decision, since it was likely to be appealed to the JCPC. “Our judgments do not make any difference there,” Strong remarked. “They do not appear to be read or considered there, and if they are alluded to it is only for the purpose of offensive criticism. . . . I mention that as a reason why I say . . . I shall not give a reason for my judgment. No powers short of the Parliament of Canada can compel me.” Though Strong remained a member of the committee until his death in 1909, he attended sessions only in 1897–1900. He sat on 28 reported appeals and had the honour of writing eight decisions, it being a “mark of intellectual respect” for a colonial judge to be invited to do so.

Also at the imperial level, Strong served on the Venezuela commission and in 1902 he chaired an arbitration panel established to resolve a minor dispute between the United States and El Salvador. His “none too diplomatic personality” was again in evidence in his criticism and confrontation with the Salvadoran representative on the panel. In 1903 Strong was rejected for the arbitration tribunal on the Alaska boundary dispute because, in the words of Governor General Lord Minto [Elliot*], he was not “big enough in the eyes of the world to pit against the U.S. Ambassador.”

Sir Samuel Henry Strong died in Ottawa six years later of “senile decay” and “cerebral softening,” and was buried in Beechwood Cemetery. He was survived by Lady Strong and their two daughters.

Somewhere between spirited and scrappy in his youth, Canada’s third chief justice had matured into irascibility. With undisputed intellectual gifts, he nevertheless seems in the estimation of R. C. B. Risk “to have been a bully and unwilling to take seriously any opinions contrary to his own.” Sir Robert Laird Borden*, recalling his own days at the bar as well as the experience of others, referred to Strong’s “preeminent intellectual qualities,” but described him as a man of “violent and bullying temperament” and sometimes given to truculency. Borden’s assessment is apt: “Neither as puisne judge nor as Chief Justice did his usefulness, in reasonable degree, approach the standard of his ability, learning and experience.”

AO, RG 22, ser.354, no.5829. Beechwood Cemetery (Ottawa), Burial records. NA, MG 29, D61: 7816–21. Globe, 14 Dec. 1892. Ottawa Citizen, 13 Dec. 1892. Ottawa Free Press, 1 Sept. 1909. Toronto Daily Mail, 14 Dec. 1892.

G. B. Baker, “Legal education in Upper Canada, 1785–1889: the Law Society as educator,” Essays in Canadian law (Flaherty et al.), 2: 68–69; “The reconstitution of Upper Canadian legal thought in the late-Victorian empire,” Law and Hist. Rev. (Ithaca, N.Y.), 3 (1985): 222. Gordon Bale, “Law, politics and the Manitoba school question: Supreme Court and Privy Council,” Canadian Bar Rev. (Ottawa), 63 (1985): 484–85. Barrett v. the City of Winnipeg (1891), SCR, 19: 374–425. R. L. Borden, Robert Laird Borden: his memoirs, ed. Henry Borden (2v., Toronto, 1938). Canada Law Journal, 28 (1892): 481, 609; 32 (1896): 647–48; 38 (1902): 61–65. Canadian biog. dict. Canadian Law Times (Toronto), 13 (1893): 50; 15 (1895): 108–10; 18 (1898): 143–44, 164–66; 29 (1909): 1044–45. The Canadian legal directory: a guide to the bench and bar of the Dominion of Canada, ed. H. J. Morgan (Toronto, 1878). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.1. DNB. C. T. Dupont, A reply to certain charges preferred by Rev. Jabez Sims, against Charles T. Dupont, visiting superintendent at Manitoulin Island, and to the report of S. H. Strong thereon ([Ottawa, 1868]). J. D. Falconbridge, “Law and equity in Upper Canada,” Canadian Law Times, 34 (1914): 1130–46. Richard Gosse, “Random thoughts of a would-be judicial biographer,” Univ. of Toronto Law Journal, 19 (1969): 597–605. F. M. Greenwood, “Lord Watson, institutional self-interest, and the decentralization of Canadian federalism in the 1890’s,” Univ. of British Columbia Law Rev. ([Victoria]), 9 (1974): 244–79. “The Honourable Sir Samuel Henry Strong,” Canadian Green Bag (Montreal), 1 (1895), no.1: 1. Huson v. the Township of South Norwich (1895), SCR, 24: 145–69, esp. 151. In re certain statutes of the province of Manitoba relating to education (1893), SCR, 22: 577–650; (1894): 651–721. Lenoir v. Ritchie (1879), SCR, 3: 575–640. Lord Minto’s Canadian papers: a selection of the public and private papers of the fourth Earl of Minto, 1898–1904, ed. and intro. Paul Stevens and J. T. Saywell (2v., Toronto, 1981–83), 2. J. [A.] Macdonald, Correspondence of Sir John Macdonald . . . , ed. Joseph Pope (Toronto, 1921). Frank MacKinnon, “The establishment of the Supreme Court of Canada,” CHR, 27 (1946): 258–74. Mercer v. Attorney General for Ontario (1881), SCR, 5: 538–712. Ontario Salt Co. v. Merchants Salt Co. (1871), Grant’s Chancery Reports (Toronto), 18 (1870–71): 540–56. Political appointments and judicial bench (N.-O. Coté). R. C. B. Risk, “Canadian courts under the influence,” Univ. of Toronto Law Journal, 40 (1990): 687–737. Paul Romney, Mr Attorney: the attorney general for Ontario in court, cabinet, and legislature, 1791–1899 (Toronto, 1986). P. H. Russell, The Supreme Court of Canada as a bilingual and bicultural institution (Ottawa, 1969). St. Catharines Milling and Lumber Co. v. the Queen (1887), SCR, 13: 577–676. Alexander Smith, The commerce power in Canada and the United States (Toronto, 1963). Snell and Vaughan, Supreme Court of Canada.

Cite This Article

Jamie Benidickson, “STRONG, Sir SAMUEL HENRY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 1, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/strong_samuel_henry_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/strong_samuel_henry_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jamie Benidickson |

| Title of Article: | STRONG, Sir SAMUEL HENRY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | April 1, 2025 |