As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

Source: Link

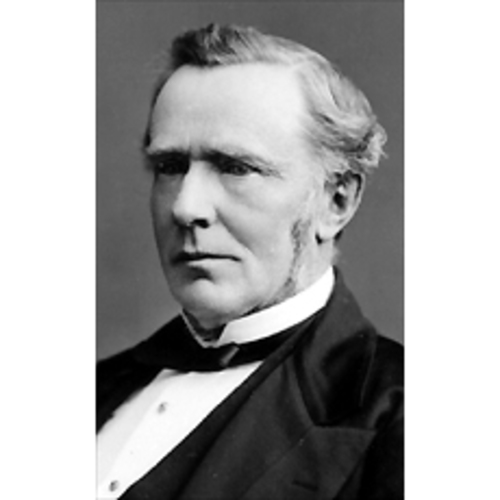

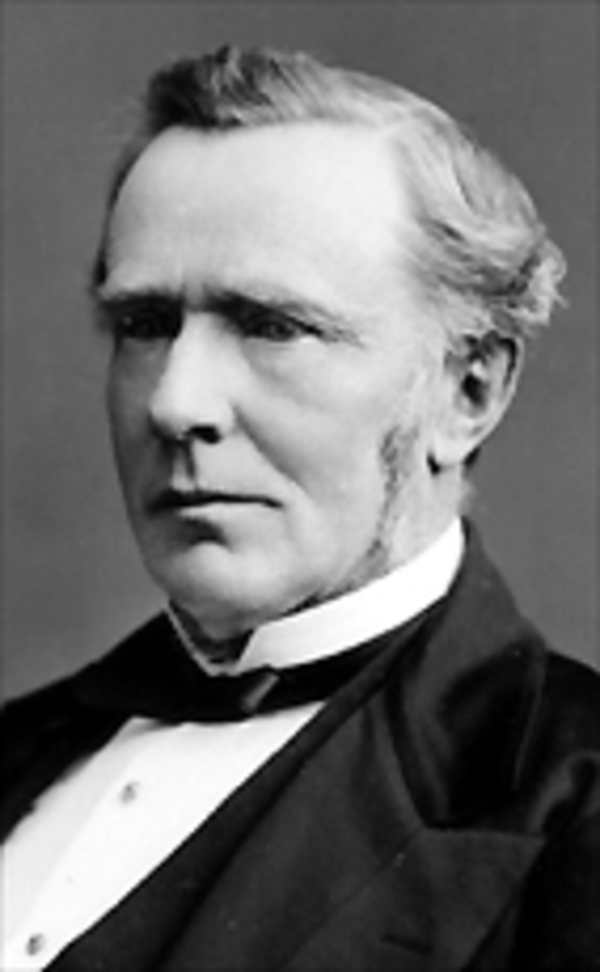

McLELAN, ARCHIBALD WOODBURY, shipbuilder, shipowner, and politician; b. 20 Dec. 1824 at Londonderry, N.S., son of Gloud Wilson McLelan*, a member of the Nova Scotia House of Assembly, and Martha Spencer; m. in 1854 Caroline Metzler; d. 26 June 1890 at Halifax, N.S.

Archibald Woodbury McLelan was educated at Great Village, on the north shore of the Minas Basin, and then at Mount Allison Wesleyan Academy at Sackville, N.B. He acquired considerable experience at sea and was managing his father’s shipping business and store in Great Village before the latter’s death in 1858. That same year McLelan succeeded his father as representative in the assembly for Colchester County, and like him supported Joseph Howe* and the Reform party. McLelan was also a charter member of the local division of the Sons of Temperance organized in Great Village in 1850.

In partnership with his brother-in-law John M. Blaikie, McLelan began to build ships on the Great Village River. In 1863 they and two other partners constructed the 257-ton Cleo, and during the 1870s McLelan and Blaikie alone built the 750-ton Wave King (1872), the 900-ton Wave Queen (1873), and the 1,200-ton Monarch (1876). They continued to build ships into the early 1880s, using timber from the hardwood, spruce, and hackmatack forests of Colchester and Cumberland counties and framing timbers from the Acadian village of Memramcook, N.B., at the head of Cobequid Bay. McLelan’s business prospered, and by 1867 it was generally understood that he was comfortably off.

With Howe, McLelan strongly opposed confederation through 1865, 1866, and after 1867. He believed the British North American provinces had disparate interests, and that the proposed financial terms were unjust to Nova Scotia. The debt allowance sounded fine in theory, and Alexander Tilloch Galt*’s idea for the equalization of debts was superficially persuasive. The debt allowance was, however, for McLelan, the wrong way round since the Canadian and Nova Scotian assets to be transferred to the new national government were not at all equal in quality. The Canadian assets of $62.5 million represented, to a considerable extent, uncollectable or bad debts while the Nova Scotian contribution of $8 million represented railways or other public works in reasonable condition that could be taken over as assets by the new dominion government. McLelan also opposed the way in which confederation had been achieved. After his election as member of parliament for Colchester in September 1867 he told the House of Commons when it met for the first time in Ottawa in November that the people of Nova Scotia had been insulted and betrayed. Although they had taken revenge at the polls by electing many anti-confederate members to the Commons, they were not yet satisfied and would try to get out of confederation altogether. While McLelan was impressed, as he himself admitted, with the power and the resources that he had now seen in Quebec and Ontario, he believed Nova Scotia could manage perfectly well on its own and that there was little or no commercial connection between Nova Scotia and central Canada. Nova Scotia probably had “more ships in the Port of Calcutta, in any day of the year, than . . . in all the ports of [the Province of] Canada.”

McLelan, with Howe, looked to Great Britain for remedy, but early in 1868 Britain refused to accept Nova Scotia’s appeal against confederation. The anti-confederates had then two choices: to continue to agitate, notwithstanding the British decision, or to make better terms with the new Dominion of Canada. McLelan and Howe took the latter course. Samuel Leonard Tilley* of New Brunswick urged the wisdom of concessions to Sir John A. Macdonald*, and so accommodation was gradually arrived at, though with great difficulty. Macdonald came to Halifax in August, and Howe and McLelan went to Portland, Maine, in January 1869 to meet with the minister of finance, Sir John Rose; “better terms” for Nova Scotia emerged. Howe took a seat in Macdonald’s cabinet on 30 January but the bitter by-election he was forced to fight the following April in Hants permanently impaired his health. McLelan resigned as mp, accepted a seat in the Senate, and became one of three commissioners for overseeing the construction of the Intercolonial Railway at a salary of $3,000 a year. It was easy to allege that Howe and McLelan had been bought off, but probably not true. McLelan certainly was a man of principle, and, so far as the evidence allows, of probity; he now believed that there was nothing else, constitutionally, for Nova Scotia to do but to accept better terms and make the best of confederation.

During the 1870s McLelan’s shipping business continued to prosper, and he also became involved in the Cobequid Marine Insurance Company. In 1875 he opposed George Brown*’s draft treaty with the United States that would allow Canadian ships to be registered in American ports since it would mean that Maritime shipyards would become shipbuilders for the Americans. It had once been the practice, notably in New Brunswick, to build ships for sale, especially to Great Britain, but, as McLelan told the Canadian Senate, “I scarcely know a man who followed that business but was ruined . . . our true policy is to build for ourselves, to build and sail our own ships.” That same year, in the Senate, McLelan supported the National Policy, something he was always to believe in.

After the return of the Macdonald Conservative ministry in September 1878, McLelan was gradually drawn closer to the government. When James McDonald*, the minister of justice, retired in 1881 to the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia, McLelan joined the Macdonald government as president of the council, Howe’s old portfolio. At the same time he gave up his Senate seat and was elected by his old constituents of Colchester County to the House of Commons. In July 1882, he became minister of marine and fisheries. He was an unusually good minister, being thoroughly familiar with the shipping business, and being by nature hard-working and judicious. Within a month of his appointment he had already visited Sable Island and all the lighthouses on the eastern coast of Nova Scotia, and was on his way up the St Lawrence to the Saguenay. Two years later, at the age of 59, he went to examine lighthouses on lakes Huron and Superior, in order, as he wrote Sir John A. Macdonald, “to deal more intelligently with the demands of mps and others for lights, buoys, beacons.” He was instrumental in organizing the meteorological bureau in the department, and in introducing a new system of gas buoys.

His tenure as minister of finance (December 1885 to January 1887) was not as successful; McLelan seems to have lacked the technical skill and probably accepted the position at Macdonald’s insistence. When replaced by Sir Charles Tupper*, McLelan became postmaster general for a year and a half, and was responsible for introducing the parcel post system into Canada. By now, however, he wanted to be out of the cabinet, and on 10 July 1888 he accepted the position of lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia with a sigh of relief.

Nova Scotians had not altogether forgotten the persuasion exerted to get McLelan to accept confederation early in 1869, but his tenure at Government House, Halifax, was happier than Howe’s had been 15 years before. His faintly bucolic style of living was more endearing than otherwise. His constituents from Colchester presented him with a fine Jersey cow, which was duly put to graze in a field at Government House and milked by the coachman; Mrs McLelan churned the butter herself since the cook refused. McLelan died rather unexpectedly in Halifax on 26 June 1890. He left a widow, three sons, a daughter, as well as at least one grandson, and, it was believed, a considerable estate.

McLelan was a man of judgement and good sense. He opposed confederation until impassable barriers has been reached, then made the best he could of it, and tried to persuade his fellow Nova Scotians to do the same. He also opposed further concessions to the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1885, along with his fellow Maritimer, the minister of finance, Leonard Tilley. He helped Macdonald strengthen the cabinet – it badly needed strengthening – in September 1885, when John Sparrow David Thompson* was brought from the Supreme Court bench in Halifax to become minister of justice. McLelan was fond of Macdonald and on 29 June 1889 wrote an appreciative letter to him: “Often when Council was perplexed and you had made things smooth and plain I have thought of the expression an old farmer made about my late father when he saw him accomplish something that had puzzled all the neighbours. ‘There are wheels in that man that have never been moved yet’ and so I have thought of my leader. . . .” He also enjoyed Macdonald’s sense of humour, even at his own expense: when he and Thompson returned to Ottawa in June 1886, after a fruitless attempt to defeat William Stevens Fielding* in the 1886 provincial election, he came to cabinet newly barbered, with his hair slicked down, and Macdonald at once observed, “Why, McLelan, you look as if you had had a good licking!” McLelan was not a brilliant man, but, like Macdonald, he seemed to have forces and powers held in reserve.

[No major collection of McLelan papers has so far turned up. Mount Allison University Library (Sackville, N.B.) has two groups of letters, under G. W. McLelan, the father, and A. W. McLelan, about 80 letters in all, mostly on family and business matters. The Dalhousie University Archives has some A. W. McLelan papers (MS 2–87). There are a few letters from A. W. McLelan in a file in PANS, under the name of G. W. McLelan. There are also letters from him to Sir John A. Macdonald in the Macdonald papers (PAC, MG 26, A, 232), in the Howe papers (PAC, MG 24, B29), and in the Thompson papers (PAC, MG 24, C4). McLelan’s speech in the Nova Scotian assembly in 1865, opposing confederation, is printed as a separate pamphlet, Speech on the union of the colonies . . . (Halifax, 1865). Something of the background of McLelan’s life is given in Great Village history, commemorating the 40th anniversary of Great Village Women’s Institute, 1920–1960 . . . ([Great Village, N.S., 1960]). There are obituaries in the Morning Chronicle (Halifax), 27 June 1890, the Morning Herald (Halifax), 27 June 1890, and the Eastern Chronicle (New Glasgow, N.S.), 3 July 1890. p.b.w.]

Cite This Article

P. B. Waite, “McLELAN, ARCHIBALD WOODBURY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mclelan_archibald_woodbury_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mclelan_archibald_woodbury_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | P. B. Waite |

| Title of Article: | McLELAN, ARCHIBALD WOODBURY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | March 29, 2025 |