As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

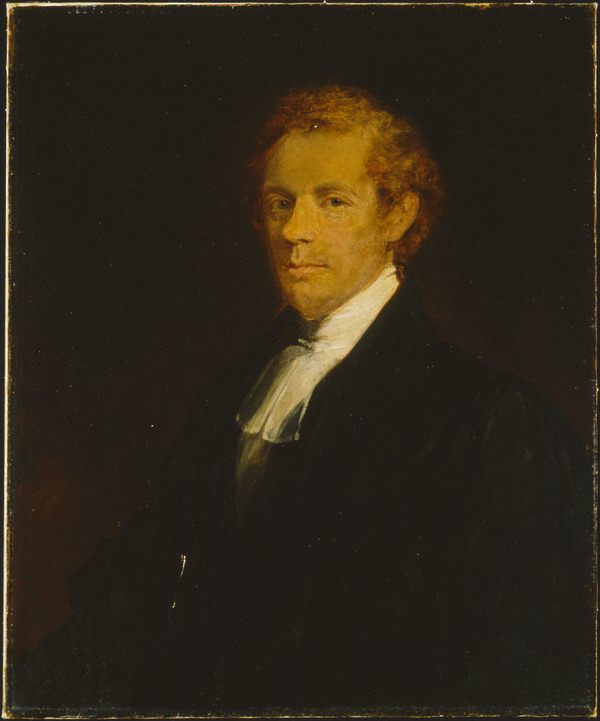

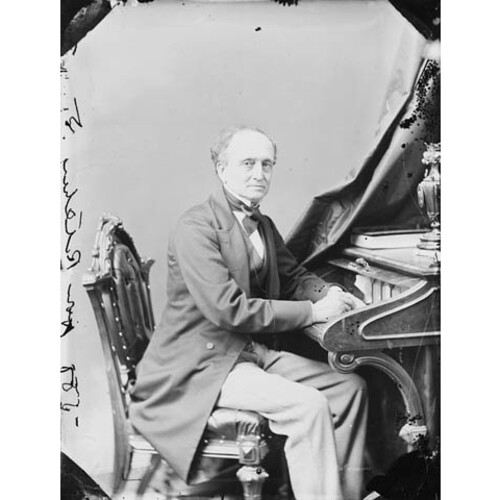

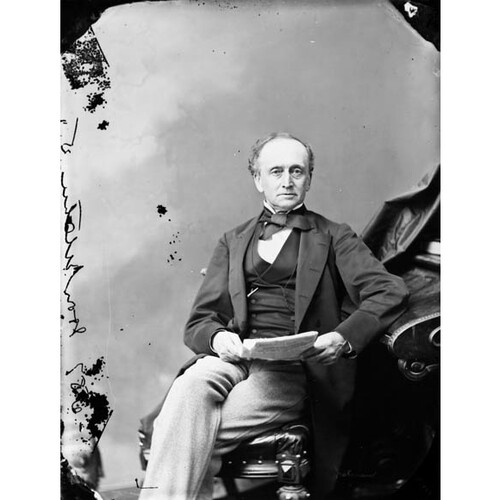

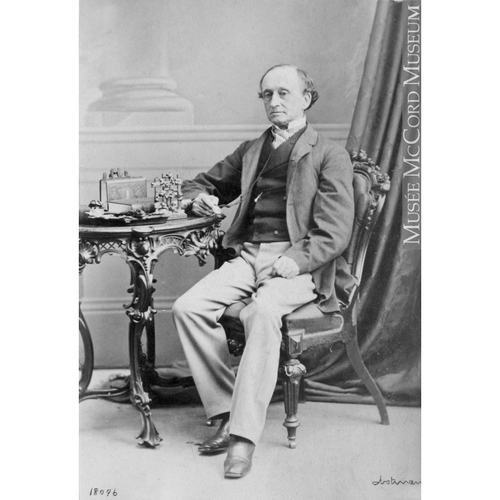

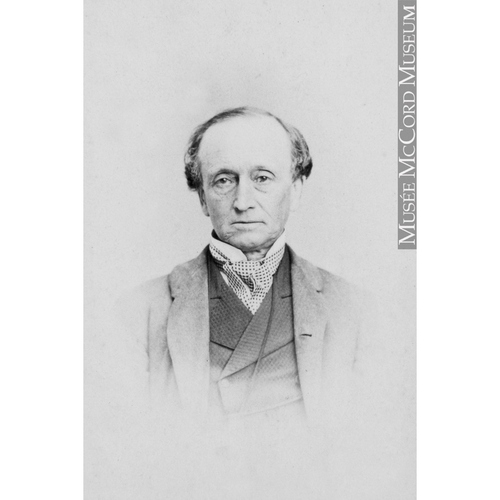

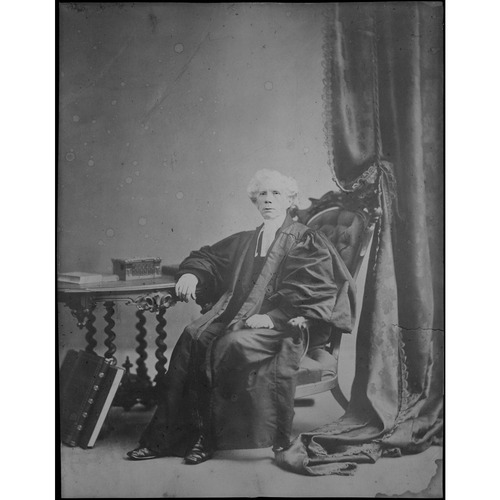

RITCHIE, JOHN WILLIAM, lawyer, legislator, and judge; b. 26 March 1808 at Annapolis Royal, N.S., the son of Thomas Ritchie*, a politician and judge, and Elizabeth Wildman Johnston; m. in 1836 Amelia Rebecca Almon, and they had 12 children; d. 13 Dec. 1890 at Halifax, N.S.

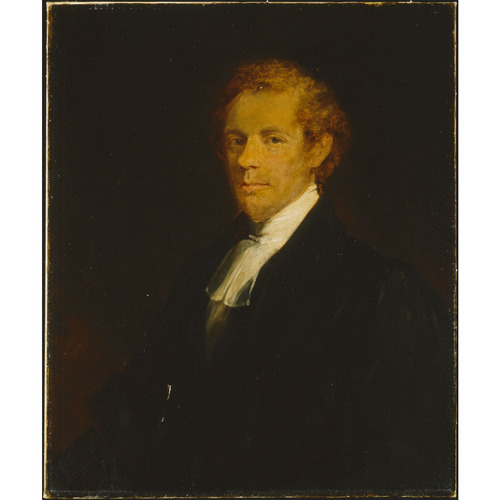

John William Ritchie’s father represented Annapolis County in the Nova Scotia assembly for many years and was a prominent lawyer and judge. John William was probably educated at Ichabod Corbett’s school in Annapolis Royal, and was later tutored at home rather than sent to college. In the mid 1820s he began studying law in Halifax with his uncle, James William Johnston*, an influential lawyer who was to lead the Conservative party for more than 20 years. Admitted to the bar as attorney in January 1831 and as barrister a year later, Ritchie had few clients in his first ten years of practice in Halifax and devoted himself to further legal studies. He was defeated in 1836 in a bid to represent Annapolis County in the assembly, a seat previously held by both his father and his uncle, John Johnston. In the same year he married Amelia Rebecca, the daughter of William Bruce Almon*, a doctor and legislative councillor, thereby continuing a tradition of intermarriage among the Ritchie, Johnston, and Almon families.

When the Nova Scotia Council was divided into separate executive and legislative bodies in 1837 Ritchie was appointed law clerk of the Legislative Council, of which J. W. Johnston and his father-in-law were members. He also began to broaden his practice and in the ensuing decade established a reputation as a gifted lawyer. In 1850 Ritchie was a member, with William Young, Jonathan McCully*, and Joseph Whidden, of a commission to revise the statutes of Nova Scotia, work he found congenial and suited to his legal training. He was an incorporator in 1856 of the Union Bank of Halifax, of which he was a director until 1866, and in December 1858 was named a qc. In 1859 the Colonial Office appointed Ritchie a member of a three-man commission to investigate the land question in Prince Edward Island. Although he represented the interests of the absentee proprietors, Ritchie agreed with Joseph Howe*, representative of the Island tenants, and the chairman, John Hamilton Gray of New Brunswick, that the tenants should have the right to buy the land on which they lived and that the imperial government should provide a £100,000 fund to facilitate land purchases. At the insistence of the proprietors, the Colonial Office rejected the commissioners’ plan, and the land question continued to bedevil Island life. A further mark of recognition was Ritchie’s appointment in 1863 to the board of governors of Dalhousie University, a post he held until his death. In 1863 and 1864 he represented St Paul’s and St George’s Anglican churches of Halifax before the legislature when they successfully opposed Bishop Hibbert Binney’s plans to incorporate a diocesan synod and give the bishop a veto over its decisions.

Like many other leading Nova Scotians, Ritchie exhibited sympathy for the Southern cause in the American Civil War. In 1864 Southern agents seized the Northern ship Chesapeake off the coast of Maine and killed one of its crew. The ship was recaptured by Northern forces, but was then escorted into Halifax by the Royal Navy. Ritchie assisted in the defence of the three New Brunswick men tried at Saint John in connection with the affair. He also acted as attorney in Halifax for his brother-in-law, Dr William Johnston Almon*, when the latter was charged with aiding the escape of the only Southern agent captured. This case never came to trial, but a representative of the Confederate states presented Ritchie with a gift of silver in recognition of the services he had provided. In accepting the gift, Ritchie praised the “almost super-human exertions” of the Southerners in defence of their “inalienable rights of liberty and property.”

In May 1864 the government of J. W. Johnston and Charles Tupper* appointed Ritchie to the Legislative Council, and he joined the cabinet as solicitor general. He soon replaced Robert Barry Dickey as government leader in the upper house and thus directed the passage through the council of important legislation dealing with common schools and Nova Scotia’s entry into confederation. Ritchie was not a delegate to either the Charlottetown or Quebec conferences of 1864 at which the form of union was decided, but in September 1865 he represented Nova Scotia at the Confederate Trade Council in Quebec where the British North American colonies considered the future of the Reciprocity Treaty with the United States and committed themselves to a common commercial policy. From the autumn of 1864 he replaced Dickey as a leading spokesman in presenting the confederation scheme to a reluctant Nova Scotia, and his contribution, according to a biographer, was “infinitely greater than anything done by Dickey who seems to have received more of the credit. . . .” Ritchie guided Tupper’s vague resolution favouring union through the Legislative Council in April 1866 and maintained close contact with Lieutenant Governor Sir William Fenwick Williams, a fellow native of Annapolis Royal, in the pursuit of the government’s unionist aims. With Tupper, Jonathan McCully, Adams George Archibald*, and William Alexander Henry, Ritchie was a Nova Scotia delegate to the London conference in the winter of 1866–67, at which the terms of union were finalized. In May 1867 he was rewarded with a seat in the Senate, and in September 1870 realized his ambitions with an appointment as puisne judge of the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia. In July 1873 he became judge in equity, in succession to J. W. Johnston and Archibald.

As a judge, Ritchie had the demeanour and the learning to make a strong impression on his contemporaries. His dignified manner and “eagle-like face . . . so clean cut and distinguished,” were coupled, in the opinion of John George Bourinot*, with “very extensive and sound” legal knowledge and “acuteness of intellect.” Robert Laird Borden* described him as “one of the ablest judges then, or at any time, on the Nova Scotia Bench,” and Wallace Graham* considered him superior in talent to his brother, Sir William Johnston Ritchie*, chief justice of Canada from 1879 to 1892. In July 1882 John William Ritchie retired from the Nova Scotia bench, having suffered ill health since 1879. He spent his retirement at Belmont, the estate he had bought in 1857 overlooking the Northwest Arm at Halifax, and died there in 1890.

John William Ritchie’s equity decisions were collected in The equity decisions of the Hon. John W. Ritchie, judge in equity of the province of Nova Scotia, 1873–1882, ed. Benjamin Russell (Halifax, 1883). As a member, with William Young, Jonathan McCully, and Joseph Whidden, of the Commission for Consolidating the Laws of the Province of Nova Scotia, Ritchie was responsible for the preparation of N.S., The private and local acts of Nova-Scotia (Halifax, 1851), and N.S., The revised statutes of Nova-Scotia (Halifax, 1851).

PANS, RG 1, 202. Acadian Recorder, 14 May 1864. British Colonist (Halifax), 3 Sept. 1864. Evening Express (Halifax), 20 July 1866. Morning Herald (Halifax), 15 Dec. 1890. J. G. Bourinot, Builders of Nova Scotia . . . (Toronto, 1900). L. G. Power, “Our first president, the Honorable John William Ritchie, 1808–1890,” N.S. Hist. Soc., Coll., 19 (1918): 1–15. C. St. C. Stayner, “John William Ritchie, one of the fathers of confederation,” N.S. Hist. Soc., Coll., 36 (1968): 183–277.

Cite This Article

Neil J. MacKinnon, “RITCHIE, JOHN WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ritchie_john_william_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ritchie_john_william_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Neil J. MacKinnon |

| Title of Article: | RITCHIE, JOHN WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | March 29, 2025 |