Source: Link

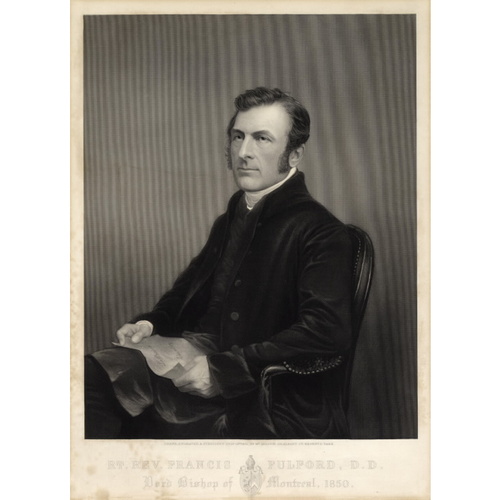

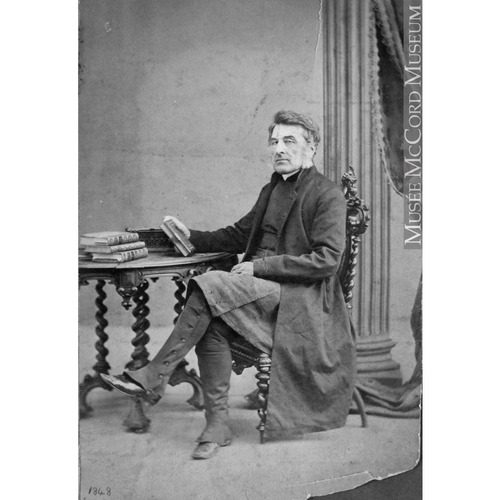

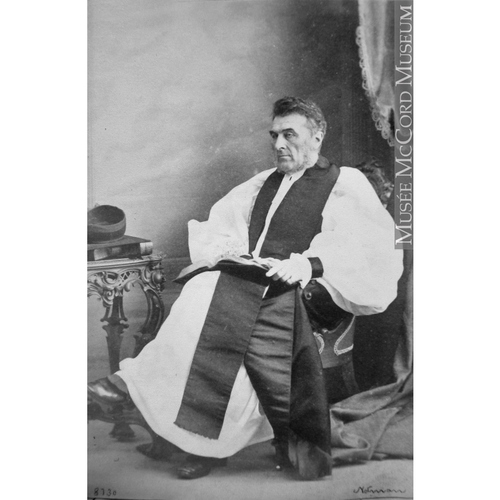

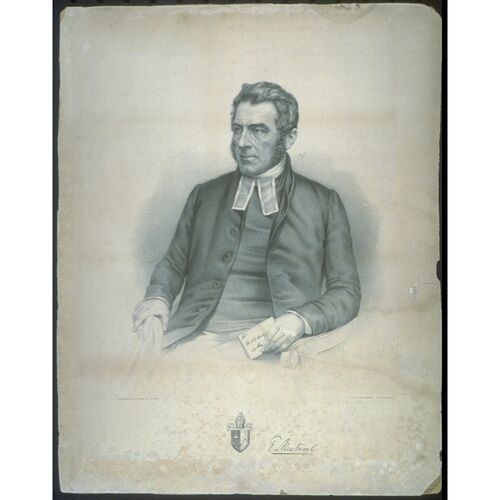

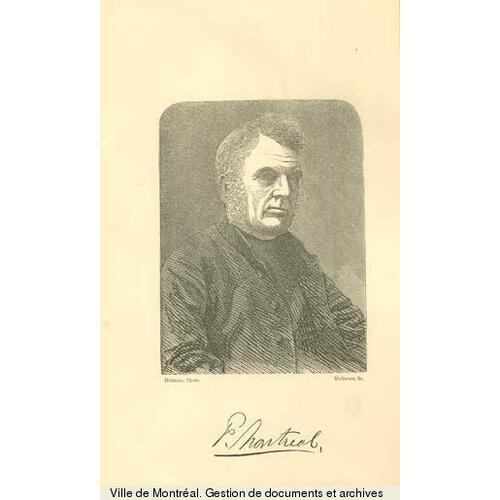

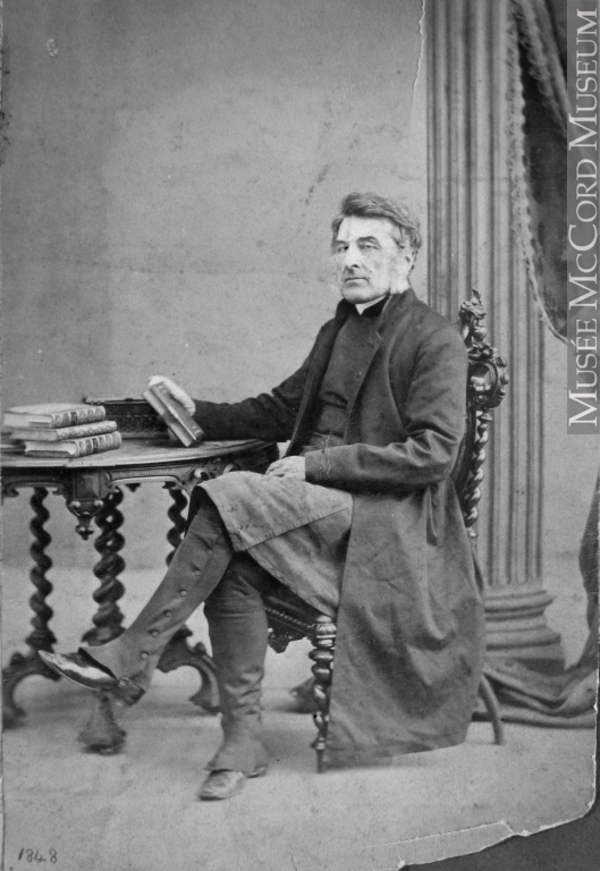

FULFORD, FRANCIS, Church of England minister and bishop; b. 3 June 1803, at Sidmouth, Devon, England, second son of Baldwin Fulford and Anne Maria Adams; m. in October 1830 Mary Drummond of Fawley, Hampshire, England; d. 9 Sept. 1868 in Montreal, Que.

Francis Fulford came of old west country stock. He was educated at Blundells School and at Exeter College, Oxford (ba 1827, ma 1838, and dd 1850). After ordination in 1828 he had extensive parochial experience in western England and at Croydon, Cambridgeshire, before becoming minister of Curzon Chapel, Mayfair, London, in 1845. He was also chaplain to the Duchess of Gloucester, an office which may have provided an entrée to court. In 1834 he had begun to figure in meetings of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel and formed a close friendship with its secretary, the Reverend Ernest Hawkins. In 1848, Fulford became editor of the Colonial Church Chronicle and Missionary Journal, an independent periodical favouring the SPG’s programme. At this point, he appears as a capable, energetic man ready to assume responsibility. He wrote with clarity and simplicity.

Fulford moved on the fringes of the church reform commonly known as the Oxford movement. With its principal tenet, complete freedom of the church from any state interference, he was in full accord. He protested when in 1843 Edward Bouverie Pusey, the real leader of the movement, was forbidden to use the university pulpit at Oxford; later, on visits to England, Fulford would stay with Pusey. With John Henry Newman he had friendly correspondence. Long afterwards, when Newman had become a Roman Catholic, Fulford delivered a sympathetic review of his Apologia pro vita sua in Montreal. Yet Fulford professed admiration for the English and generally for the Continental reformers of the 16th and 17th centuries. His pamphlet, The progress of the reformation in England (1841), is an index of his independent position: “[Our] Anglo Catholic Church was a reformed church.” He drew encouragement from its spread overseas, in the English colonies and in non-English countries.

The choice of Fulford for the projected diocese of Montreal probably came through his association with the SPG. The division of the diocese of Quebec was a project of long standing. George Jehoshaphat Mountain used the title bishop of Montreal as suffragan to Charles James Stewart*, and even when he succeeded him as bishop of Quebec, allegedly to keep the claims of Montreal before the authorities in Britain. By 1849 the necessary funds for an episcopal endowment were available. Hawkins inspected the proposed diocese of Montreal and conferred with Lord Elgin [Bruce] and Bishop Mountain. The Montreal clergy and laity were understandably disturbed, and their leader, the Reverend John Bethune*, tried to marshal opinion in favour of a conference that would recommend a candidate for consecration. Bethune professed to fear that the Executive Council, consisting of “members of the Church of Rome, Protestant Dissenters and only two or three Episcopalians,” would make the recommendation. In the event, the Colonial Office seems to have turned to the SPG and the Reverend Francis Fulford was its choice.

Letters patent were issued by the queen in 1850 setting up the diocese of Montreal and naming Francis Fulford lord bishop, a title enjoyed by only one other Canadian prelate, the bishop of Quebec. The diocese was coterminous with the judicial district of Montreal, an elongated triangle with its base on the United States border, its western boundary on the Ottawa River, and its eastern at the districts of Trois-Rivières and Saint-François. Christ Church, the old Protestant parish church of Montreal, was designated as the cathedral. Since the legality of letters patent in colonies exercising self-government was in question, Fulford later supplemented his through legislation by his diocesan synod. He was consecrated on 25 July 1850 in Westminster Abbey by the archbishop of Canterbury, John Bird Sumner, four English bishops, and one Canadian bishop, John Strachan of Toronto.

On 15 Sept. 1850, Fulford was enthroned in Christ Church as the spiritual head of some 25,000 adherents of what contemporaries called “the United Church of England and Ireland.” In the main they were Anglophones, but there were French speaking families and congregations in the Richelieu valley and elsewhere, such as Sainte-Thérèse, Rawdon, and Saint-Hyacinthe, missions among the Germans in the Ottawa settlements, and one for Abenaki Indians at Saint-François-de-Sales (Odanak). The complexities of his charge Fulford explored in a quick survey in the late autumn. In town and countryside he found depression, spiritually and materially. “The people are disunited & . . . few . . . [are] in reality Church people.” Their horizons were narrow; that they were parts of a societas perfecta et universalis they had no comprehension. Fulford did not despair. He liked his clergy, who numbered 48. As he came to know his people Fulford began to draw out his own lines.

In diocesan administration he had a clear field, since before 1850 there had been no special provision for the Montreal area. He began with what was closest, a cathedral chapter with dean and canons, which would exercise authority during the bishop’s absence or in the event of his death. Actually, the chapter’s powers were limited to the management of the cathedral church and membership was honorific. Nevertheless, John Bethune could boast that he was the first dean of any Anglican jurisdiction in North America. In 1855 Bishop Fulford named an archdeacon for the whole diocese; he became the executive assistant, a hard-worked, much-travelled dignitary. To encourage local initiative, Fulford in 1859 marshalled the missions and parishes into four rural deaneries, St Andrews (northern), Hochelaga and Iberville (central), and Bedford (southern). Ruridecanal meetings of laity and clergy made possible projects beyond the resources of a single charge, did something to break down isolation, and smoothed decision-making at higher levels. The efficiency and esprit de corps the diocese rapidly achieved may be ascribed largely to Fulford’s local organization.

Fulford inherited a Church Society. Ten years old in 1850, the society was divided between the dioceses of Quebec and Montreal. This association of fee-paying members, charged with the administration of finances, was reorganized by Fulford into committees (education, church extension, etcetera) and he encouraged branches in the missions. Much of the society’s effectiveness was owing to its principal officers – Thomas Brown Anderson*, the treasurer, and Strachan Bethune, the legal adviser-and to its élite of lay members who included George Moffatt and William Badgley*.

In synodical organization Fulford showed great persistence. As early as July 1851, the Montreal Church Society debated the possibility of setting up a synod. To his primary visitation (January 1852), Fulford directed each of his clergy to bring two laymen, although traditionally the visitation was exclusively clerical. Observation of a diocesan convention of the American Protestant Episcopal Church reinforced his preference for strong “lay influence.” Two meetings of Montreal clergy and laity in 1853 were held to consider William Ewart Gladstone’s bill before the British parliament to “amend the laws relating to the Church in the Colonies.” Fulford, ready to set up a synod, was surprised when clerical and even lay opposition showed itself. The laymen were chiefly lawyers, such as Thomas Cushing Aylwin*, who affected to believe that the overseas church, cut off from the state, could not govern itself. Fulford adroitly took advantage of the opposition by obtaining Canadian legislation giving legal recognition to the synod in 1857 and 1858.

A constitution proposed for synod observed three “orders”: bishop, clergy, and laity. The lay members would be communicants elected by the various charges; the Church Society, in contrast, was composed of fee-paying members. Another difference was the power the synod would have to enact regulations (canons) binding on its members. (When in 1867 the Church Society was merged with the synod and thus disappeared, all authority was brought under representative and responsible control.) To be legal, canons of the synod would require the concurrence of the three orders. Many of the original opponents of the synod now opposed what they called “the Bishop’s veto,” since the bishop formed one order. Fulford out-manœuvred this group, and the constitution he wished was adopted in 1859.

Financing of the diocese was a continuing preoccupation. Apart from the episcopal endowment (capital £10,000), there was no regular income. Following 1854, as part of the, clergy reserves settlement, the diocese received about £10,500 when the clergy commuted their life interest in the reserves in favour of the church. The Church Society (and after 1867 the synod) began diocese-wide collections to maintain the clergy. Grants were made by the SPG but, in Fulford’s view, they would have to be eliminated as soon as possible. To make the charges of the diocese self-supporting, he instead encouraged systematic giving by their people, and favoured local endowments in money or in land. Between 1859 and 1864 the SPG also assisted in the acquisition of glebes, contributing over £1,100.

Within the diocese after 1854 lay some 190,000 acres of undisposed clergy reserve land, roughly estimated at £30,000. Fulford doubted the validity of the Church of England’s claims, and also the wisdom of pushing them. Nevertheless, he signed with his fellow bishops a petition to the British government for their retention. In 1855 he commented with detachment on the progress of secularization, deploring Strachan’s vigorous protests, although admitting that they were “[all] too true as to facts.” Possibly, like his predecessor, Bishop Stewart, Fulford appreciated contemporary Canadian attitudes towards the public endowment of denominational bodies, and was unwilling to expose his church to obloquy.

Early in his episcopate Bishop Fulford considered extensive church building but hope of it was dispelled as he came to grips with diocesan finance. Only after destruction by fire in December 1856 of the old cathedral on Notre-Dame St could anything on a large scale be done. A new site was secured on Sainte-Catherine St and Frank Wills designed a church generally resembling Fredericton Cathedral (itself apparently inspired by Snettisham Church in Norfolk). The new cathedral, opened on Advent Sunday 1859, completely satisfied Fulford’s hopes: “There is no building to compare with it on this Continent.” A less subjective judgement would describe it as a fine example of Gothic architecture, although of minute proportions.

Francis Fulford was deeply concerned with schooling in all its phases. From his first arrival he took an active part in Bishop’s University, from which he secured a number of his clergy. He was vice-president and enjoyed with the bishop of Quebec (the president) visitorial powers. With McGill University his relations were cooler, possibly because of John Bethune’s embroilment in that institution.

Parochial schools and the perennial problem of supplying staff drew him into the earliest and possibly the most serious controversy of his episcopate. In 1851 he was informed that the Colonial Church and School Society proposed to enter his diocese. This organization, formed by the amalgamation of other religious or educational societies, was controlled by a committee in England which posted missionaries (pastors and schoolmasters) and set up schools independently of the diocesan bishops. Fulford’s position was the more difficult since one of his principal Montreal clergymen, William Bennett Bond* of St George’s Church, became the local agent of the society. At the same time Fulford had to recognize the benefits of trained teachers. A compromise was made. He became the president of the Montreal Committee of the Church and School Society, and hence effectively director of local operations; thus his episcopal authority was recognized. The society maintained schools throughout the diocese, and in Montreal replaced the declining National School [see John Bethune]. In 1853 the society introduced William Henry Hicks*, an experienced teacher, as headmaster of a central, or teacher-training, school in Montreal, which supplied masters and mistresses for the diocesan schools; in 1856 Fulford permitted it to act as the Normal School of McGill University, and it became the chief supplier of Protestant teachers for Quebec.

The society was a factor in Fulford’s work among Francophones. It maintained the churches and schools at Iberville and Sabrevois begun by William Plenderleath* Christie. At Saint-Jean a training college was organized to prepare the French speaking teachers and ministers required, chiefly in the missions round Lac Maskinongé and on Île Jésus, for congregations of converted French Canadians and also for groups of Anglo-Canadians, who, through living among French Canadians, had become French speaking. In 1859 a more concerted effort was made with the incorporation of the Church of England Mission to the French-speaking population of British North America, with Fulford as chief patron. He had little in common with the French Canadian Missionary Society, which contained few Anglicans. Not a proselytizer, he was, however, determined his church should minister to both English and French.

In 1860 Bishop Fulford became the first metropolitan of the ecclesiastical province of Canada. Petitions in favour of creation of a province had begun much earlier. In 1861 letters patent declared Montreal to be the metropolitan see with Fulford and his successors enjoying the dignity. To him legal vexations fell early. The bishop of Huron, Benjamin Cronyn*, was disposed in 1861 to question Fulford’s authority under the letters patent. Fulford’s reply was decisive: “I told him that I was in the Chair & meant to keep it – that I should never stultify myself or insult the Queen [by permitting a question on the validity of the letters patent].” However, more powerful dissolvents were at work. Decisions of the imperial Privy Council on several disputes in 1863–65 involving the metropolitan of South Africa destroyed the authority of letters patent. In Canada legislative action by the provincial synod provided a new, contractual basis of authority, and Fulford’s powers as metropolitan were never effectively challenged.

Nonetheless, in 1864 the bishop of Huron again tried, with the counsel of Edward Blake*, his son-in-law, and Adam Crooks*; their legal opinion came close to invalidating the system of provincial synodical administration. Fulford was fortified by a contrary opinion from his chancellor, Strachan Bethune. John Hillyard Cameron*, however, the distinguished Canada West lawyer, insisted that the provincial synod rested on consensus, buttressed by a Canadian statute, as well as on the letters patent, and since Blake and Crooks had admitted the synod might be based on “voluntary association,” even Bishop Cronyn was silenced.

In 1863 Fulford consecrated James William Williams* bishop of Quebec on the authority of a royal licence; in 1867, when Alexander Neil Bethune* was made suffragan to Strachan, election by the synod of the diocese of Toronto was deemed sufficient before the consecration. Thus it fell to Bishop Fulford as metropolitan to signal the autonomy of the Canadian church.

Fulford was engaged throughout 1862 in a lengthy and complicated debate with Archdeacon Isaac Hellmuth* of Huron. Eleven years earlier Hellmuth had been one of Fulford’s subjects in the Montreal diocese, and the two had differed over a real estate deal involving Hellmuth’s father-in-law, Thomas Evans, who had promised an interest-free loan and land for a church on Sherbrooke St, with Hellmuth to be the first incumbent. In Fulford’s view, Hellmuth had irretrievably compromised himself. Late in 1861 Hellmuth was sent on a collecting tour in England for the theological institution Bishop Cronyn proposed in London, Canada West. This plan reflected the quarrel between Bishop Cronyn and Trinity College, Toronto, of which, as metropolitan, Fulford was forced to take cognizance. Deeply deploring it, he was indignant to learn that in England Hellmuth claimed evangelical clergy to be at a “discount” in the Canadian church and positive Protestant teaching to be lacking in Canadian colleges. Between April and July, Fulford launched three hard-hitting pastoral letters condemning Hellmuth’s extravagances. The dispute over the Montreal church was raked out and Hellmuth was bracketed with Father Charles-Paschal-Télesphore Chiniquy* as “a very astute and successful collector of funds” – a cutting comparison considering some of Chiniquy’s transactions. Fulford may have won in the polemics, but his victory scarcely contributed to harmony within the ecclesiastical province.

Fulford preached before the triennial convention of the American Protestant Episcopal Church at Philadelphia in October 1865. It was a momentous meeting, being the first of any national representative body after the ending of the Civil War. Fulford’s closest contacts had been with the bishops of New England and New York, but he had received clergymen from the Confederacy into his diocese. Fulford wrote: “Mine was a very plain ordinary sermon except that it just did hit the right note . . . & the breach, I trust, is effectively healed.” The continuing fellowship with the church in the United States was shown on 6 June 1867 when four American bishops (Maine, Vermont, Illinois, and Virginia) took part in the consecration of the Montreal cathedral.

In 1867, Fulford took an active part in the first world meeting of Anglican prelates at Lambeth, England. As early as 1852, in a letter to Hawkins deploring the defection of friends “to Rome,” he wrote, “Nothing will tend more to stop that evil than some real united action of all the Reformed Episcopal Churches, our own, home, colonies, Scotch & American.” The appearance in 1860 of Essays and reviews, disturbing to conservative theologians, and, beginning in 1863, the protracted scandal in South Africa, favoured his pleas. He returned to the theme in the first provincial synod of 1861 and at the second, in 1865, his views were put in a formal resolution to the archbishop of Canterbury. With Bishop Samuel Wilberforce of Oxford, perhaps the chief English advocate of the conference, Fulford was on intimate terms. At the conference itself, Fulford pressed for a strong declaration of independence of the church, and possibly as recognition was asked to preach on 28 Sept. 1867 before the final meeting in Lambeth Church. (For some unexplained reason Fulford was absent when the historic group photograph of this first Lambeth Conference was taken.)

On this same visit to London Fulford had a leading part in another event: “Saturday 16 Febr. I attended at St. George’s Hanover Square and officiated at the marriage of the Honble [John Alexander Macdonald*] Attorney Gen’l for Upper Canada and president of the Delegates.” This is one of his few references to the meeting in London of the Canadian political leaders negotiating the final terms of the British North America Act.

For some years Fulford’s health had been failing, but in spite of this his last months of life were especially laborious in activities of the diocese. On 9 Sept. 1868 he died. He had intended to make the findings of the Lambeth Conference the subject of the forthcoming synod’s deliberations, determined as he was to head off a discussion of ritualism, already a divisive issue elsewhere in Canada. With ritual as such he had no quarrel, but he disliked ecclesiastical finery. He preached in a plain black gown, often extemporaneously.

Anthony Trollope would not have found Bishop Fulford a sympathetic subject. He had few interests beyond the care of his scattered and struggling flock, but this care included more than spiritual comfort and guidance. He had a keen aesthetic sense and was one of the founders of the Montreal Art Association. He was interested also in adult education, conceived along self-help lines, and thus supported the Montreal Mechanics’ Institute and the Church of England Young Men’s associations. Within his own communion Fulford stressed the virtues of self-support and self-government, from the level of the individual mission to the ecclesiastical province itself. The characterization of him as “master-builder” was not unwarranted.

Francis Fulford, A letter to the bishops, clergy, and laity of the United Church of England and Ireland in the province of Canada (Montreal, 1864); A pastoral letter addressed to the clergy of his diocese (Montreal, 1851); A pastoral letter to the clergy of his diocese (Montreal, 1851). Anglican Church of Canada, Diocese of Montreal, Synod Archives (Montreal), Correspondence with the secretaries of the SPG, 1850–60 (photocopies); Francis Fulford, miscellaneous notes, memoranda. Anglican Church of Canada, General Synod Archives (Toronto), C. H. Fulford, “Life of Bishop Fulford” (typescript). The Lambeth conferences of 1867, 1878, and 1888, with the official reports and resolutions, together with the sermons preached at the conferences, ed. R. T. Davidson (London, 1889). A memoir of George Jehoshaphat Mountain, D.D., D.C.L., late bishop of Quebec . . . , comp. A. W. Mountain (Montreal, 1866). C. R. Bell, General index of the proceedings of the first eleven synods of the diocese of Montreal . . . (Montreal, 1872). Notman and Taylor, Portraits of British Americans, I, 15–23. The controversy between the lord bishop of Montreal and the Ven. Archdeacon Hellmuth, with opinions from the press and letters from correspondents . . . , ed. A. E. Taylor (London, [Ont.], 1863). J. I. Cooper, “The beginning of teacher training at McGill University,” A century of teacher education, 1857–1957, addresses delivered during the celebration of the centenary of the McGill Normal School (Montreal, 1957); The blessed communion; the origins and history of the diocese of Montreal, 1760–1960 ([Montreal], 1960). T. R. Millman, Life of Charles James Stewart. C. F. Pascoe, Two hundred years of the S.P.G.: an historical account of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, 1701–1900 . . . (2v., London, 1901). The progress of the reformation in England, to which are added two sermons, by Bishop Sanderson . . . (London, 1841). [J.] F. Taylor, The last three bishops, appointed by the crown for the Anglican Church of Canada (Montreal, 1869).

Cite This Article

John Irwin Cooper, “FULFORD, FRANCIS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 23, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fulford_francis_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/fulford_francis_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | John Irwin Cooper |

| Title of Article: | FULFORD, FRANCIS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1976 |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | November 23, 2024 |