As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

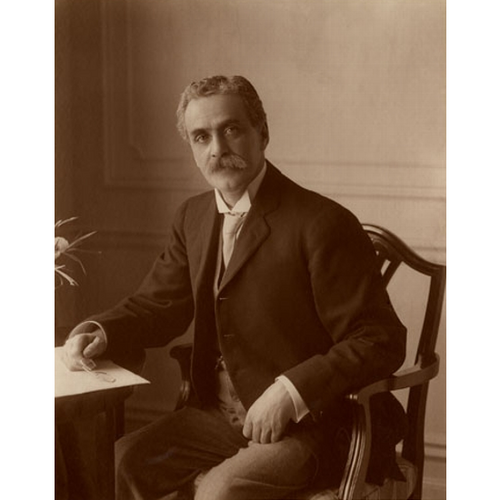

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

PELLETIER, LOUIS-PHILIPPE (baptized Louis-Thomas-Godfroi), lawyer, journalist, newspaper owner, politician, professor, and judge; b. 1 Feb. 1857 in Trois-Pistoles, Lower Canada, son of Thomas-Philippe Pelletier, a merchant and later a legislative councillor, and Caroline Casault, sister of Louis-Napoléon Casault, a politician and future chief justice of the Superior Court of the province of Quebec; m. 11 Jan. 1883 Adèle (Adélaïde) Lelièvre at Quebec; they had no children; d. there 8 Feb. 1921.

Raised in a rather intellectual and conservative family environment, Louis-Philippe Pelletier entered the Collège de Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière at the age of 11, together with his brother Alphonse, who was 13; one of his fellow students was Thomas Chapais*. In 1877 he began his studies in law at the Université Laval in Quebec City. Three years later he obtained his degree “with great distinction,” along with the Tessier prize and the gold medal awarded by the governor general, the Marquess of Lorne [Campbell*]; he was articled to Auguste-Réal Angers*, an influential Conservative lawyer with whom he would become friends.

Called to the bar on 17 July 1880, Pelletier embarked upon a long and fruitful career in law. He practised in Quebec City first in the office of Blanchet, Amyot et Pelletier, then in 1889 with the prominent firm Amyot, Pelletier et Fontaine, and in 1903 with Drouin, Pelletier et Baillargeon. In the end he became head of the firm Pelletier, Baillargeon et Alleyn, before being named a judge in 1914. In the meantime, he was appointed a qc on 7 March 1893, was given an honorary doctorate by the Université Laval on 10 June 1902, and was chosen as legal counsel to several banks and firms. He sat on various boards of directors, sometimes even as president, notably of the Canadian Electric Light Company, which used the hydroelectric power of the Chaudière falls, near Quebec City. From 1907 until his death, he was a professor in the faculty of law of the Université Laval.

It was, however, through his political activity on the provincial and federal levels that Pelletier gained renown. In 1885 the Riel affair [see Louis Riel*] moved him to side with those who condemned the hanging of the Métis chief, considering it an affront to French Canadians. President of the Club Cartier of Quebec, he resigned from that body and joined the “national alliance” led by Honoré Mercier*, which was made up of dissident Liberals and Conservatives. From 1886 to 1891 Pelletier supported the national program through La Justice, a newspaper he founded in January 1886 at Quebec with other National Conservatives. Idealistic and ultramontane, he believed in an alliance reaching beyond partisan lines and private interests which would uphold the fundamental principles of French Canadian society, and he was unrelenting in his efforts to demonstrate the importance of the church in the social fabric. He ran in the provincial election in Témiscouata on 14 Oct. 1886, but was defeated by a Conservative, Georges-Honoré Deschênes*; a candidate again in the federal election of 22 Feb. 1887, he lost in Trois-Rivières to Sir Hector-Louis Langevin* by only 30 votes. To reward him, Mercier, who had become premier, named him to the Legislative Council on 11 May 1888. He thus received the title of honourable and could now participate in the legislative process. Dissatisfied, he managed to switch places with Louis-Napoléon Larochelle*, the mla for Dorchester, a seat Pelletier won by acclamation in a by-election on 20 December. A crucial period in his career began then. An ordinary backbencher, he was entrusted by Mercier with the task of ensuring that Lieutenant Governor Auguste-Réal Angers cooperated in providing royal assent to bills.

Pelletier again won in Dorchester in the election of 17 June 1890 which gave Mercier’s Parti National a comfortable majority. Anxious to put forward his more liberal ideas, Mercier soon found him an obstacle. He publicly rebuffed Pelletier because he expressed reservations about the bill to ensure medical control of insane asylums by the state; then, because La Justice did not give unqualified support to the government, he had him removed as editor of the paper early in 1891. Ousted thereby from the Parti National, Pelletier naturally turned to his former party and before long his influence on its ideology and strategies was noticeable. He managed to establish a party newspaper, Le Matin (Québec), to counterbalance L’Électeur, the organ of the Liberals in Quebec; the paper was published from January to September 1892.

In December 1891 the Baie des Chaleurs scandal led to the downfall of the Mercier government, and the Conservatives under Charles Boucher* de Boucherville took power. At 34, Pelletier, who was known to be hard-working, well informed, and full of fighting spirit, was named secretary and registrar in the new administration as of December; he retained this office under Conservative premier Louis-Olivier Taillon from 1892 to 1896, and then was attorney general in Edmund James Flynn’s ministry from May 1896 to May 1897. As minister, Pelletier demonstrated his tendency to embrace the ultramontane vision of an orderly management of finances and a minimally interventionist administration; this approach to governing was based on traditional French Canadian values and sought to maintain the status quo for the structures of power and social organization, particularly in areas under the control of religious institutions.

Re-elected on 11 May 1897, despite the Liberal wave that swept across Quebec, Pelletier entered a long period in the opposition. Late in 1904, when Premier Simon-Napoléon Parent* precipitated a provincial election, he backed his party in its decision not to participate. He would try, but without success, to get elected to the provincial, and then to the federal parliament in 1908. Chief organizer of the federal Conservative party for the district of Quebec from 1903, Pelletier gradually let himself be seduced by the nationalist ideas of Henri Bourassa* and the Ligue Nationaliste Canadienne, which had been founded that year by Olivar Asselin*. Reconciling Conservative principles with nationalist ideals then became the key that would enable Pelletier to act on the federal scene as an advocate for a form of pan-Canadian nationalism based on traditional values. Through L’Événement, of which he was one of the owners from 1903 to 1914 [see Louis-Joseph Demers*], he supported the alliance between Bourassa and Frederick Debartzch Monk* and the new Conservative-Nationaliste formation resulting from it in 1910. The newspaper even clearly distanced itself from Conservative leader Robert Laird Borden* with regard to Sir Wilfrid Laurier*’s controversial plan for a naval service; the paper held that the leader “is mistaken, is deluding himself about the dangers to the empire, about Canada’s obligations to the mother country.” In the federal election of 21 Sept. 1911, which brought the Conservatives to power, Pelletier won in the riding of Quebec as a Conservative with a Nationaliste allegiance. He represented a minority faction within the Borden government, but remained confident of getting along well with the Conservative party from which he had come. Postmaster general from 10 Oct. 1911 to 19 Oct. 1914, Pelletier applied himself to improving rural and regular postal delivery, the various services in post offices, and the working conditions of employees.

Two major questions quickly brought Pelletier into conflict with those within the Borden government who supported an imperialistic nationalism. Strongly influenced by a type of imperialism extolled by Britain, this nationalist approach showed little sensitivity when it came to the rights and institutions of French Canadians. The issue of protecting the educational rights of Keewatin’s francophone Catholic minority emerged in 1912, when part of this large district was to be joined to Manitoba. Faced with the intransigence of his cabinet colleagues, who refused to put guarantees for the Catholic minority in the act transferring the area to that province, Pelletier had no option but to give in or resign. He chose to accept the negotiations that were going on at the same time with the Manitoba government of Sir Rodmond Palen Roblin* with the objective of obtaining a promise to reduce school taxes for Catholics throughout the province. Then, the Borden government’s plan to provide financial aid to the British navy again brought his nationalist convictions into play. A trip to Britain along with Borden in the summer of 1912 convinced him of the threat posed by the Germans and of his slim chances of preventing the adoption of this plan. Again he tried the route of compromise, endeavouring to have every military aid project subjected to a plebiscite, which would make it more acceptable in the eyes of the nationalists. Despite Borden’s firm refusal and Monk’s resignation on 18 October, Pelletier chose to remain in the cabinet. To some people his decision looked like a definitive abandonment of nationalist ideals. It seems, however, that Pelletier was more the victim of political circumstances militating against advocacy of his ideals and that he preferred to stay to ensure the presence of a nationalist in the cabinet, rather than resign and let the protagonists of the imperialist and Orange ideal retain power by themselves. In October 1914 he submitted his resignation, before being named a judge of the Superior Court for the district of Montreal on 18 November; he was transferred to the Quebec Court of King’s Bench on 20 Aug. 1915. He presided, notably, over the trial in April 1920 of Marie-Anne Houde, who was accused of murdering her stepdaughter, Aurore Gagnon*, known as Aurore the martyred child.

Louis-Philippe Pelletier’s triple career, which pursued legal, journalistic, and political paths, was impressive although not unusual for its time. It is, however, the period he spent in the federal government that is of particular note, for it illustrates Pelletier’s inability to give effect to his nationalist ideals as well as the difficulties he experienced in upholding a French Canadian vision and French Canadian values within a government strongly influenced by imperialist ideology.

[A detailed study of Louis-Philippe Pelletier’s political career, including relevant primary and secondary sources, is provided in the author’s dissertation “Louis-Philippe Pelletier: un exemple du douloureux mariage du mouvement nationaliste et du Parti conservateur fédéral (1911–1914)” (mémoire de ma, univ. Laval, Québec, 1991). d.g.]

ANQ-Q, CE301-S1, 11 janv. 1883; CE303-S30, 1er févr. 1857.

Cite This Article

Danièle Goulet, “PELLETIER, LOUIS-PHILIPPE (baptized Louis-Thomas-Godfroi),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pelletier_louis_philippe_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pelletier_louis_philippe_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Danièle Goulet |

| Title of Article: | PELLETIER, LOUIS-PHILIPPE (baptized Louis-Thomas-Godfroi) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | March 28, 2025 |