![Description Sir Peregrine Maitland, KCB [Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada, 1818-28] Date c. 1882-1883 Source This image is available from the Archives of Ontario under the item reference code 693136 This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Commons:Licensing for more information. English | Français | Македонски | +/− Author George Theodore Berthon (1806-1892) Permission (Reusing this file) This is a faithful photographic reproduction of an original two-dimensional work of art. The work of art itself is in the public domain for the following reason: Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse This image (or other media file) is in the public domain because its copyright has expired. This applies to Australia, the European Union and those countries with a copyright term of life of the author plus 70 years. You m Original title: Description Sir Peregrine Maitland, KCB [Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada, 1818-28] Date c. 1882-1883 Source This image is available from the Archives of Ontario under the item reference code 693136 This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Commons:Licensing for more information. English | Français | Македонски | +/− Author George Theodore Berthon (1806-1892) Permission (Reusing this file) This is a faithful photographic reproduction of an original two-dimensional work of art. The work of art itself is in the public domain for the following reason: Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse This image (or other media file) is in the public domain because its copyright has expired. This applies to Australia, the European Union and those countries with a copyright term of life of the author plus 70 years. You m](/bioimages/w600.1388.jpg)

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

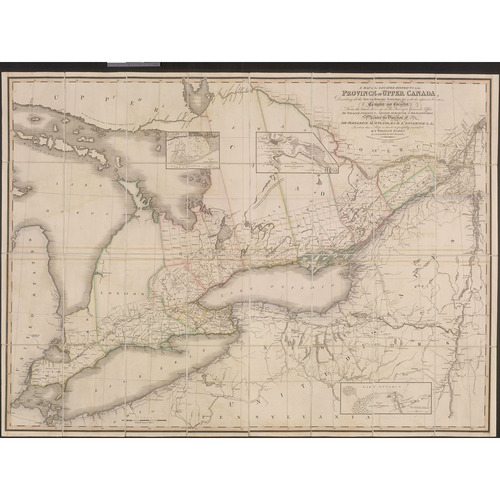

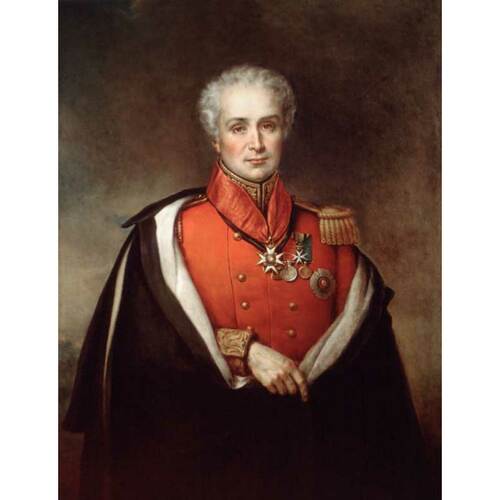

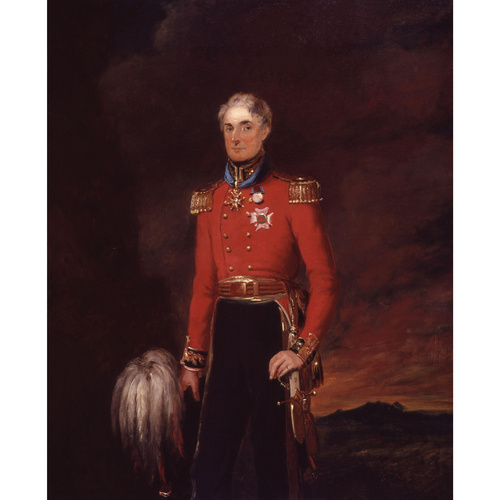

MAITLAND, Sir PEREGRINE, army officer and colonial administrator; b. 6 July 1777 at Longparish Hall, Hampshire, England, son of Thomas Maitland and Jane Mathew; m. first 8 June 1803 Louisa Crofton (d. 1805), and they had a son, Peregrine; m. secondly 9 Oct. 1815 Lady Sarah Lennox, daughter of Charles Lennox*, 4th Duke of Richmond and Lennox, and they had at least seven children, one of whom died in infancy; d. 30 May 1854 in London.

At the age of 15 Peregrine Maitland entered the British army as an ensign in the 1st Foot Guards. He quickly rose in rank, becoming a captain in 1794 and a lieutenant-colonel in 1803. During the Napoleonic Wars he served with his regiment in Spain, Flanders, and France. Promoted major-general in 1814, he was made a cb on 4 June 1815. Later that month he commanded the 1st brigade of the Foot Guards at the battle of Waterloo. He was subsequently placed in charge of the 2nd brigade, which formed part of the occupation force in Paris following the defeat of Napoleon. For this role he was created a kcb on 22 June.

While he was in Paris, his second marriage, to Lady Sarah Lennox, took place – an event to which both myth and romance have become attached. According to one story, recorded by both Henry Scadding* and David Breakenridge Read*, Maitland and Lady Sarah eloped because of her father’s objections to Maitland’s suit. It was thought there was too great a difference in their ages (he was 38, she was 23) and she had been expected to marry a man of higher station. Richmond’s disapproval was overcome, it is said, through the intervention of the Duke of Wellington, at whose quarters in Paris the two were married. Maitland’s marriage proved to be an advantageous one politically. There was, apparently, no lingering discord between him and his father-in-law, and when Richmond was appointed governor-in-chief of British North America in 1818, his influence was one factor in Maitland’s appointment that year as lieutenant governor of Upper Canada, succeeding Francis Gore. Other factors were involved: Maitland was a personal friend of Lord Bathurst, the colonial secretary, and the British government wished to make places for its war heroes.

Maitland arrived in York (Toronto) on 12 Aug. 1818 and was sworn in the following day. He would remain in office for the next ten years, serving as well a brief term as administrator of Lower Canada from 17 March to 19 June 1820. The Reverend John Strachan*, who was to become one of his political allies during the 1820s, described him in December 1818 as “a most amiable and pious man, . . . most anxious to do all the good he can.” He was a man “of great talent . . . much simplicity of manner and habit,” and “at the same time firm and resolute,” though extremely delicate in health. In June 1820 Lord Dalhousie [Ramsay*], the governor-in-chief, noted that he seemed to be “in rapid consumption.” Henry Scadding recalled him as “a tall, grave officer, always in military undress; his countenance ever wearing a mingled expression of sadness and benevolence.”

During his first year in office Maitland became “exceedingly popular from his quiet gentlemanlike manners, & the firm unassuming tone of his Government,” as Dalhousie recorded after talking with William Dummer Powell*, speaker of the House of Assembly. Maitland was undoubtedly aided socially by his wife’s “distinguished style.” In York he was instrumental in setting up an elementary school on Lancasterian principles [see Joseph Spragg*], and he appointed a board of trustees for the proposed first general hospital [see Christopher Widmer]. Confronted by the town’s dreary streetscapes, he was confident in 1819 that a few public works would “induce a sentiment of national pride”; five years later he laid the cornerstone for the Home District’s first court-house and jail, designed by John Ewart.

But Maitland was never enamoured of the provincial capital. No doubt he considered it, as others did, an unhealthy site. During his stay in Upper Canada he built a 22-room summer house, Stamford Park, three miles west of Niagara Falls. In the opinion of Anna Brownell Jameson [Murphy] in 1837, it was the only place in Upper Canada “combining our ideas of an elegant, well-furnished English villa and ornamental grounds with some of the grandest and wildest features of the forest scene.” Maitland’s dislike of York prompted him to investigate moving the provincial capital elsewhere. Between 1822 and 1826 he had properties purchased on the east shore of Lake Simcoe with a view to moving the capital there. In 1826 he suggested Kingston as a site. The locations were recommended by Maitland because both were more defensible than York, and Kingston had the potential for better accommodating government officials.

Soon after his arrival in Upper Canada in 1818, Maitland had conveyed to the Colonial Office reports that a man named Gourlay had been “perplexing” the province. A number of leading officials in Upper Canada, many of whom would be Maitland’s advisers during his administration, must have considered this a temperate description of the situation in the province. Believing that the constitution was endangered, they viewed with alarm the colony’s tendency to sedition under the influence of “turbulent and factious men.” Within a year Maitland informed the Colonial Office that reports of serious disturbances had been exaggerated.

At the centre of apprehension was Robert Gourlay*, a sincere but erratic and tactless Scottish radical, who had come to Upper Canada in 1817. Through his wife’s relatives there and as a result of his tour of the western part of the province, Gourlay became aware that economic expectations following the War of 1812 had given way to dissatisfaction, which was particularly acute in the Niagara District. The war had been followed by economic depression; compensation to those who suffered war losses had not been made; land promised to militiamen had not been granted; capital necessary for development was inadequate; settlement remained scattered and there was little demand for land. Particularly frustrating to the large landholders was the continuation of a wartime prohibition on American settlement. In April 1817, shortly before Gourlay’s arrival, Robert Nichol*, a member of the House of Assembly for Norfolk who had considerable property in the Niagara District, had secured the establishment of a legislative committee to investigate the state of the province. Full debate on its resolutions was prevented by Lieutenant Governor Gore, who had pre-emptorily prorogued the legislature. His reaction to what he considered a censure of the administration of the province would be reflected in Maitland’s response first to Gourlay and then, during the 1820s, to sustained opposition within the assembly.

In 1817–18, through a series of newspaper addresses, questionnaires, and the promotion of township meetings of landowners and inhabitants, Gourlay condemned the administration. As well, he planned a provincial convention of township delegates, out of which would come a petition to the Prince Regent. When, instead, a petition was presented to Maitland by two members from the convention, held in York in July 1818, the new lieutenant governor refused to accept it, expressing his disapproval of the action by stating that the convention had been irregular and hostile to the spirit of the British constitution, since the people had lawful representatives in the legislature. A convention of delegates could not exist, said the Legislative Council in an address to Maitland, without danger to the constitution. He subsequently recommended legislation prohibiting “seditious” conventions and meetings such as Gourlay had organized; he dismissed from civil and military appointments, or denied them to, any who had supported Gourlay. In echoing Maitland’s speech opening parliament in October 1818, the assembly accepted Maitland’s recommendation and banned conventions “as highly derogatory and repugnant to the spirit of the Constitution.”

Accounts of the emergence of a political opposition in Upper Canada in the 1820s and 1830s have asserted that members of the executive attempted to persuade successive lieutenant governors to accept their perception of executive authority as it should be exercised. Those in this influential group changed from time to time. The period of Maitland’s administration saw the eclipse of Chief Justice William Dummer Powell as the chief legal adviser to the lieutenant governor and the rise of Attorney General John Beverley Robinson*. Along with Maitland’s secretary, Major George Hillier*, Robinson and John Strachan were undoubtedly the most influential members of Maitland’s administration. Hillier had served with Maitland in Europe and was a close friend as well as an adviser. He was an efficient and capable individual whose views coincided with those of Maitland and on whom the lieutenant governor relied in carrying out the routine business of administration and often in formulating reports and dispatches. At the end of 1818 Strachan, a member of the Executive Council and later of the Legislative Council, was not yet on terms of intimacy with Maitland but already he felt he had exerted some influence. “He arrived here,” said Strachan in December, “with some ideas respecting the Executive Government not founded on sufficient evidence; but now he sees things more clearly.”

In Maitland’s case no conversion was necessary. He was of a decidedly conservative persuasion. His over-reaction to Gourlay and to public meetings or conventions reflected an intrinsic part of his political disposition and was directly related to the political unrest in Britain during 1816–19. At the time of his arrival in the province, response in Britain to economic dislocation following the Napoleonic Wars had led to demands for the reform of parliament, for universal suffrage, and for voting by ballot, all promoted by a post-war revival of political associations, mass meetings, and conventions. This revival became associated with the democratic excesses of the French revolution and led in 1817 and again in 1819 to legislation in Britain suspending habeas corpus and to a prohibition on public meetings, political clubs, and the sale of seditious literature. The suppression of public meetings and limitation of the freedom of the press were commended by Upper Canadian conservatives, who believed that public agitation was both dangerous and disloyal. Maitland concurred in this belief throughout the 1820s. The agitation by Gourlay aroused public discussion and interest in the affairs of the province, as he had intended. Maitland found himself increasingly in conflict with a group of oppositionists who were critical of his administration and of the conservative advisers with whom he surrounded himself.

Maitland did recognize that some of the grievances identified by Gourlay’s agitation, as they related to the granting and distribution of land, were legitimate. Soon after arriving in Upper Canada he had informed Lord Bathurst of the harmful effects of absentee ownership of land. He subsequently made himself acquainted with the history of the land-granting system in Upper Canada and made a genuine attempt to curb abuses and to institute reforms. Yet he was not always free to determine land policies, being subject to joint control with imperial authorities. Many of his efforts were hindered by the influence of land speculators and by an agrarian-oriented assembly, which resisted the taxation of wild land. Even his critic William Lyon Mackenzie* recognized the problem of dealing with such vested interests and later gave Maitland credit for the limited improvements he had been able to effect. One of Maitland’s first reforms was to bring some efficiency and energy to the work of the provincial land board, which had become a cause of constant complaint and which he accused in August 1818, the month of his arrival, of “sleeping over an office choked with applications.” Within a month he was able to report to the Colonial Office that the derelict board had “brought up a long arrear of business.”

Maitland had inherited the problems of an earlier policy of liberal and extensive grants of crown lands to loyalists, militia, pensioners, and officials – much of which remained unoccupied and uncultivated. Actual settlers complained it was their labour that increased the value of the lands of absentee owners and speculators. Despite strong opposition from a number of officials and the landowners, who argued that, in the existing state of Upper Canada’s economy, it was unprofitable to lay out money on agriculture, a bill authorizing the taxation of uncultivated land was passed in 1819. Maitland believed the tax would induce owners to develop or sell their land. Since the Assessment Act of 1819 was a temporary measure, it was made permanent in 1824, despite the resistance of those members of the assembly and Legislative Council who, Maitland noted, “were the largest land proprietors.” He believed that only his personal pressure in the Legislative Council, where W. D. Powell opposed the new act, secured its passage. In 1828, however, it was modified by the assembly to favour the owners of land who were tax-delinquent.

Maitland’s criticism of the policy of liberal grants of crown land recognized that it had not been effective in settling the province, and settlement had been dispersed. Between 1818 and 1823 he recommended that grants be limited, that lands be used to produce revenue for supporting education and road-building, and that all grantees be forced to perform the settlement duties before receiving patents. By an order in council in 1819, he set up district land boards to examine applicants and make locations of land, thus relieving the provincial board of much of this work. To Maitland the land system of Upper Canada had a political as well as an economic purpose. Lands should be used to develop support for the provincial administration and to make Upper Canada as attractive to immigrants as the United States. In achieving these ends it was essential for the executive to be financially independent from the assembly, which did not share his imperial enthusiasms. During Gore’s administration, the assembly had demanded control of the revenue from crown lands and reserves, a trend which Maitland met head-on. Early in 1819 he informed the assembly that the casual and territorial revenue was not at its disposal. He nevertheless attempted to correct the province’s financial problems by trying to make the land department self-supporting and to devise a method of making the crown reserves productive. In 1823, in a dispatch to the Colonial Office, he concluded that the only practical policy was to dispose of lands by sale instead of by grant, a proposal originally made by John Beverley Robinson to offset the province’s growing financial burden [see John Henry Dunn].

In 1826 the reserves not leased or applied for in townships surveyed before March 1824 were sold along with the Huron Tract to the Canada Company, which on the basis of sales made an annual payment to the province. These payments supported the civil administration and helped to make it independent of the assembly. Though satisfied with this arrangement, Maitland experienced an irritating relationship with the Canada Company’s agent in Upper Canada, John Galt*. Maitland considered him hostile to his administration and too sympathetic to his critics, including William Lyon Mackenzie, John Rolph*, and Marshall Spring Bidwell*. Galt’s practice of communicating directly with the Colonial Office disturbed Maitland, who as lieutenant governor was justifiably concerned with maintaining executive control.

All of Maitland’s efforts in the field of land reform were directed at the economic development of the province. He sought to discourage speculation and to promote actual settlement. He encouraged (in contrast to Lord Dalhousie) Peter Robinson*’s development of settlement in the Peterborough area and supported Thomas Talbot in opening up much of the southwestern part of the province. He welcomed immigration schemes, such as the £10 deposit plan of 1818 [see Richard Talbot], that would add to the British content of the population and thereby counteract American republican influences.

The question of the influence and status of the many American immigrants in Upper Canada was not a new one. It had been implicit in the community since its birth, but only took shape as a divisive issue in 1821–22 during the bitter debate surrounding the election to and expulsion from the assembly of Barnabas Bidwell*, a native of Massachusetts. He channelled the complex legal and moral arguments into a lasting accusation that he had been expelled by an administration intent on stripping all unnaturalized residents of their civil rights. The controversy over Bidwell’s eligibility, and that of his son Marshall Spring at a by-election in 1822, suggested that a new doctrine was being established, under which many inhabitants who had come from the United States after the Treaty of Paris of 1783 would be considered aliens, unqualified to vote, ineligible to sit in the assembly, and incapable of legally owning lands. If carried into execution the doctrine would disenfranchise a large proportion of freeholders in every district of the province. Maitland and his supporters, believing that the growing opposition to the administration emanated from this portion of the populace, sought to limit its power in the assembly. Oppositionists, for similar political reasons, sought to force the recognition of the political and property rights of this group. Maitland had been aware of the problem for some years. In 1820 he had stated to Dalhousie that a “very large portion” of property in the province was in the hands of Americans “who had not complied with the terms of residence,” and that if the laws of citizenship and naturalization were enforced “you would now unsettle more than half the possessions of the Colony.”

In an atmosphere of tension and anxiety over the question of citizenship and naturalization, Maitland sought the advice of the Colonial Office in April 1822. He did not set out to dispossess the American-born of their property but he was firm in his desire to exclude from election to the assembly those whom he considered to be aliens. He believed exclusion was essential to the security of Upper Canada. The assembly, on the other hand, requested from the imperial government in 1823 an assertion that the American-born be guaranteed the rights of British subjects. The controversy over the Bidwells brought the alien question fully into the open as a highly charged political issue. Since a related case (Thomas v. Acklam) was pending in the British Court of King’s Bench, no reply was received from the Colonial Office, though there was some indication that the imperial government subscribed to Maitland’s point of view. Based on the court’s decision in 1824, the British law officers ruled that both Bidwell and his son were aliens and could not sit in the assembly. Further, all inhabitants who had willingly stayed in the United States after 1783 and accepted American citizenship had forfeited their British allegiance. Recognizing that it would be advisable for the Upper Canadian legislature to pass an act naturalizing aliens and admitting them to the “civil rights and privileges of British subjects,” Lord Bathurst authorized Maitland in July 1825 to have appropriate legislation prepared. In November the provincial government brought into the Legislative Council a bill “to confirm, and quiet in the possession of their estates, and to admit to the civil rights of subjects, certain classes of persons.” The assembly, however, rejected the government bill, which was vaguely worded and avoided specific mention of political rights for naturalized residents. As a result of the general election of late 1824, the assembly contained, for the first time, a clear-cut majority of anti-government members. Among these was John Rolph, the first man who could effectively stand up in the house to John Beverley Robinson, probably Maitland’s closest adviser on the alien issue. In the session of 1825–26 an alternate bill was narrowly passed in the assembly, declaring that the parties affected had always been British subjects. This bill was unacceptable to the administration, but in January 1826 the opposition argued, correctly, that its bill only asserted what had been official doctrine until some time after the War of 1812 and had, moreover, constituted the understanding on which most of the colony’s population had settled there.

In May the imperial parliament attempted to resolve the problem by passing a statute which empowered the Upper Canadian legislature to bestow, within the province only, all the rights and privileges of British subjects (including political rights). Bathurst then sent Maitland a dispatch outlining the terms of a provincial act that would be acceptable to the imperial authorities. They included provisions (in particular one that made naturalization conditional on the beneficiary’s abjuration of his American allegiance) which were obnoxious to those affected. When the Naturalization Bill was brought in in 1827, it was accepted by the opposition only with great reluctance, under the threat that, if it were defeated, the parties affected would be unable to vote in the next general election. Opponents to the bill organized the Committee of the Inhabitants of Upper Canada and sent Robert Randal* to London with a petition asking that royal assent be withheld. To Maitland’s dismay, Randal was successful. The imperial government rejected its former view that people could abjure their natural allegiance; consequently the Upper Canadian bill requiring resident aliens to do just that had to be disallowed. Annoyed and humiliated, Maitland was directed to prepare new legislation at the next session, failing which appropriate measures would be enacted at Westminster. He treated the task as a capitulation to his critics and, in his own defence, argued that both Upper Canada and the Colonial Office had been deliberately misled by malignant forces within the province and by radical elements in Britain.

In the session of 1828, as Maitland later viewed it, the members of the assembly were seeking issues “to sustain their popularity” in the expected election. Bitterness erupted when Maitland transmitted the Colonial Office dispatch directing new legislation and provoked the assembly by charging members with exciting “groundless alarm” among the inhabitants of the province. In retaliation, the members stated the necessity for them to reply to insults and to charges of misconduct and misrepresentation made by the lieutenant governor. Maitland, however, was fighting for a lost cause. The Colonial Office had decided against him and in 1828 the required Naturalization Bill was passed favouring the views of the anti-government forces. Throughout the debate Maitland repeatedly argued, in public and in dispatches to the Colonial Office, that the language of the act of 1828 was much like that rejected by the opposition in the bill of 1826. By ignoring the important differences of intent, particularly on political rights, Maitland may have been attempting, in an altogether devious manner, to discredit the opposition for needless rejection of the legislation of 1825. The alien question, though now closed, to the relief of many, left a legacy of enmity that served to intensify the antagonism between the assembly and the executive branch of the government. As an issue in the political education of the community it served to increase public awareness of the political process. John Willson, speaker of the assembly, remarked in February 1828, “It had been difficult to awaken the people from their slumber but they had at last been roused to save their liberties; their complaints were now heard.”

The confrontation over the alien issue provided the assembly with an opportunity of by-passing the lieutenant governor in its criticism of the administration and its submission of petitions and resolutions to the Colonial Office. In the process the lieutenant governor was transformed from an impartial reporter of provincial events, for the information of the Colonial Office, to a spokesman for a faction, which was forced to compete with the opposition for the support of the colonial secretary. During the 1820s the assembly departed from traditional practice, deferral to the lieutenant governor on the speech from the throne, by criticizing and debating Maitland’s addresses. Maitland considered this action an affront to his prerogative. In 1826, when the assembly did not adhere to the practice of forwarding petitions and resolutions through the lieutenant governor and with the concurrence of the Legislative Council, Maitland was annoyed. He did not wish to prevent the forwarding of petitions to London, but he was firm in his belief that they should be channelled through him. His military background and training made him, as a civil administrator, punctilious in matters of rank, position, and protocol. Temperamental and acutely conscious of his imperial position, he treated the action of the assembly as a “remarkable” departure, which exhibited disrespect for the representative of the crown and gave credence to grievances manufactured by unprincipled agitators. In the last few years of his administration he became bitter in his criticism of the Colonial Office, which in his opinion was too inclined to accept censure of his administration by spokesmen whose opinions were not worthy of consideration without giving him an opportunity of stating his own case.

Soon after the 1825–26 session, Maitland had begun a tour of the province and in numerous communities he received addresses from the inhabitants. The tour seems to have been designed to create support for his policies, which had suffered a defeat in the alien issue. The universal tone of admiration for Maitland in the addresses and their approval of his administration lend credence to later charges, in the Upper Canada Herald and in the assembly, that John Strachan and John Beverley Robinson had organized and “manufactured” the tour.

Maitland’s tour and his public criticism of the assembly excited widespread counter-criticism. In one district, notice was given that a petition would be presented to the legislature asking it to institute an inquiry into Maitland’s charges accusing persons of sedition, of disaffection, and of an intention to overthrow the constitution of the province. In his opening speech to the 1826–27 session of the legislature, Maitland referred to his tour, during which, he said, he had found proof of advancement within the province and evidence of content. The spirited response in the assembly indicated the extent to which opposition members had been aroused by his actions. John Rolph led the attack, thrashing out at both Maitland and the pro-administration forces. He reproached the lieutenant governor for travelling through the province “purposely to libel and slander” members of the assembly and for “accepting slanders as loyal and affectionate addresses.” One member, George Hamilton*, was reminded of the days of Robert Gourlay’s agitation and noted the parallel between the organization of the townships by that critic and the organization of the townships by Maitland’s supporters. Gourlay’s attempt, however, had been treated as sedition.

During Maitland’s tenure the claims of the Church of England, most notably in relation to the clergy reserves, emerged as a highly divisive political and religious problem, adding to the litany of grievances against Maitland. Under the Constitutional Act lands had been set aside for the support and maintenance of a “Protestant Clergy” by means of a leasing system. Prior to Maitland’s arrival, it had been charged that the reserves, because of their chequered location throughout the townships, retarded settlement. Any attack on the reserves met with their spirited defence by John Strachan, who sought to make exclusive use of them for the benefit of the Church of England. In 1819 he had been instrumental in the development of the Upper Canada Clergy Corporation, a body of members of the Church of England who would supervise and administer the lands. The same year, following the request of a Presbyterian church in the Niagara District for financial assistance, Maitland asked the Colonial Office to determine whether the Church of England, as Strachan claimed, had the exclusive right to the reserves under the Constitutional Act. The British attorney general and solicitor general were of the opinion that the clergy of the Church of Scotland could be included in the definition of “Protestant Clergy” under the act. Maitland was not in accord with this interpretation and attempted first to prevent the opinion of the law officers from becoming known in Upper Canada and then to evade its implication by suggesting that the Church of Scotland be limited to “occasional” assistance. Maitland had aligned himself with Strachan in the view that the state should have an established church and that, in Upper Canada, the established church was the Church of England. Any other view, in Maitland’s opinion, would not be consistent with the British constitution. When the Church of Scotland pressed its claim, he asserted in 1824 that Strachan was “perfectly in my confidence” and was “fully in possession” of his views on the reserves.

Maitland, like Strachan, believed that only through support of the Anglican clergy and a system of education controlled by that clergy could Upper Canada overcome the dangerous republican ideas which, it was thought, were infiltrating the province through American Methodist clergymen and teachers. Because Methodists and Presbyterians formed such large, and vocal, segments of the population, the exclusive claims made by the Church of England could not escape becoming entangled in the political struggle between Maitland’s administration and the anti-government opposition. Maitland became identified as an opponent by those forces that resisted the exclusive claims of the Church of England, sought the separation of church and state, and wished to see the revenue from the clergy reserves devoted to general education. Maitland was not prepared, he informed William Huskisson, the colonial secretary, in 1827, to see “the national church” degraded to a sect and all denominations “placed on a level.” He admitted that Methodists “exceeded greatly” Anglicans and Presbyterians, but he did not accept finality in denominational attachments. Men who had been zealous Presbyterians in Scotland had become exemplary and active supporters of the Church of England in Upper Canada. Like Strachan, he believed that many who were only nominally attached to other denominations could be won over to the Church of England if it received the proper support.

Maitland’s support of the Church of England and his identification with Strachan proved damaging to him personally and to his administration. Strachan had been pleased at Maitland’s appointment in 1818 because the lieutenant governor was “exceedingly disposed to promote the cause of religion and education.” As a result of William Morris’s attempts in 1823 in the assembly to have the Church of Scotland recognized as a national church, the religious issue became a focus of public attention. Partly to divert the clamour and hoping to increase the revenue of the Church of England, Strachan, with Maitland’s concurrence, went to London in 1826 to continue negotiations with the Canada Company for the sale of the clergy reserves. At the same time he sought to obtain a charter for a provincial university under the control of the Church of England. The establishment of a university had constantly been on Maitland’s mind since his arrival in the province, the purpose being, he said, “to produce a common attachment to our constitution, and a common feeling of respect and affection for our ecclesiastical establishment.” When Strachan went to London, Maitland wrote to the Colonial Office stating that nothing would gratify him more than to see Strachan’s purpose implemented. While in London Strachan prepared an “Ecclesiastical Chart” that blatantly exaggerated the place of his church in the life of Upper Canada. Following his return to the province in the summer of 1827 he was easily challenged on his chart and denounced for his continuing derogation of the Methodists. The charter for a university was condemned. Even some of his fellow-churchmen were disturbed by his actions.

Though Maitland did not abandon his principles, he was upset by Strachan’s zeal, which, he maintained, only served to inflame the debate on the claims of the Church of England. Reports circulated that a rupture between the two had developed, though no open manifestation of any change was detected. The bitterness the issue had aroused, Maitland said, was a result he had not anticipated. The debate on the chart and the university was a climax to one of the most acrimonious confrontations of the 1820s. Opponents rose up to challenge what they damned, in the Upper Canada Herald in October 1827, as an attempt to impose on the province an illiberal and exclusive “clerico-political aristocracy” alien to the Upper Canadian situation. In December, at a meeting in York, a petition, to which 8,000 signatures were obtained, was drawn up challenging Strachan’s position on both the clergy reserves and the university [see George Ryerson*]. In March 1828 the assembly sent a petition to the Colonial Office requesting revocation of the university charter.

Toward the end of Maitland’s administration Strachan’s excesses had clearly became a liability. The lieutenant governor ignored Strachan’s “Ecclesiastical Chart” and attempted instead to blame much of the agitation on those who misrepresented the Church of England and on the vacillations of the imperial government. But in the election of 1828 the province would register its disapproval of Maitland and his advisers. “There can be no question,” Samuel Peters Jarvis wrote to W. D. Powell in December 1828, “that much of the odium, which has fallen to the share of many of those who were conspicuous in the late administration, was caused by his [Strachan’s] uncompromising disposition.”

By 1828 Maitland was being accused of authoritarian, vindictive, and Draconian measures. Charles Fothergill*, the king’s printer, had been warned that the views expressed in his newspaper were unacceptable to Maitland. He was dismissed in 1826 for voting in the assembly against the administration and for being the “mover and conductor” of a “committee on grievances.” He was replaced by Robert Stanton*, whose views were more in accord with those of the lieutenant governor and his advisers. In 1827 Maitland sent troops to remove an enclosure built on a government reserve by William Forsyth*, a Niagara Falls innkeeper. A committee of the assembly, made up of anti-administration men, supported Forsyth and reported the incident of military interference as one of a number of “unprecedented outrages perpetrated by the administration.” The Colonial Office censured Maitland for his part in the incident. Judge John Walpole Willis*, who came to Upper Canada in 1827, associated with anti-government men. Maitland saw him as a man attempting to become a popular leader of an anti-administration cause. Aware that the retirement of Chief Justice William Campbell* was imminent, Willis sought the office, but Maitland strongly disapproved. When Willis challenged the authority of the Court of King’s Bench, claiming that it was “incompetent” as a court in the absence of the chief justice, Maitland, after consulting the province’s law officers, suspended him. William Lyon Mackenzie called the action “executive tyranny” and Willis became a hero to the anti-administration forces. A further example of the attacks on dissent came when Francis Collins*, editor of the Canadian Freeman and author of a pamphlet on the alien issue, was found guilty of libelling John Beverley Robinson in 1828.

The election of 1828 constituted a climax to the confrontation between Maitland’s administration and the anti-government forces. The extent to which a polarization of attitudes had taken place was exhibited in the extreme partisanship of the electoral candidates. One, Thomas Dalton* in Frontenac, believed that Upper Canada needed to be saved from the oppression of the pro-administration group; another, Alpheus Jones in Grenville, withdrew from the election, believing that there was little hope of defeating the “radicals” who were hostile to Britain and whose purpose was to turn Upper Canada into a republic. Almost every political issue or incident of the 1820s was a matter of electoral discussion – the clergy reserves, the university charter, Willis’s removal, the treatment of Forsyth, and the alien question. The result was a thorough defeat of the pro-administration candidates and a more hostile reform assembly than that of the 1824–28 period. It was not, Maitland reported, “such as could be wished.” He attributed it to “busy but obscure individuals” who had made use of the alien question. In characteristic fashion, he saw it as the victory of “notoriously disloyal” men, men of “detestable” character who “degraded the legislature by their presence.”

Later in 1828 Maitland received another rebuff and experienced a further sense of betrayal by Britain. As a result of meetings held in York that summer, a petition was drawn up and sent to both the crown and the Colonial Office, listing a series of Upper Canadian grievances. Prominent in the list was the dismissal of Willis, the composition of the Legislative Council, the “practical irresponsibility” of the Executive Council, and (in direct reference to Maitland) the “total inaptitude of military men for civil rule in this province.” The petition was occasioned by what the petitioners perceived to be the “liberal sentiments” expressed in the House of Commons and by the “favourable consideration” accorded Robert Randal’s petition on the Naturalization Bill in 1827. Gratitude was expressed to two British radicals, Sir James Mackintosh and Joseph Hume who, the petition claimed, had been attentive to the rights of British subjects in Upper Canada. Early in January 1829 William Warren Baldwin*, chairman of the meetings at York, wrote to the prime minister, the Duke of Wellington, making references to the “misrule” that had crept into the administration of Upper Canada and recommending the adoption of the principle of a local “ministry” responsible to the “Provincial Parliament.”

Maitland was infuriated by the petition, seeing it as a further censure of his actions. In September 1828, in a lengthy statement to Sir George Murray*, the colonial secretary, he refuted the charges made against him and belittled both the petition and the petitioners, whom, with the exception of Baldwin and his son Robert, he viewed as men of little social standing, men who had no character as gentlemen. They were “American Quack Doctors, a tanner, Shoemakers, Butcher and Penny postman.” In Maitland’s mind, that was sufficient to deny them and their opinions any serious consideration by the imperial government.

Prior to the debate on the York petition, the House of Commons, in response to petitions from Upper and Lower Canada, had appointed a committee of inquiry into the government of the Canadas. In its report, which reached Upper Canada in the autumn of 1828, many of the criticisms of the Maitland administration were accepted – judges should not be members of the Executive Council (and thus politically involved as advisers to the lieutenant governor), clergy reserves retarded development and should be brought under cultivation, the Church of England should not have an exclusive right to the reserves and its control of the proposed university should be curtailed. The report was so favourable to the views of the opposition that Maitland was again compelled to express his frustration and anger at William Huskisson’s liberal policy on colonial matters and the imperial government’s readiness to accept the criticism which “any unprincipled partisan of faction” carried across the Atlantic. His supporters, already disturbed by the defeat suffered in the election of 1828, were equally enraged.

Maitland left office as lieutenant governor of Upper Canada on 4 Nov. 1828, a result, many believed, of the complaints against him. The extent of the reform domination of the assembly was clearly reflected in the vote, early in 1829, on the assembly address expressing dissatisfaction with Maitland’s administration. In carrying the address, 37 to 1, the assembly administered a decisive rebuke to Maitland and his supporters. As a result, opposition men were hopeful that the appointment of Sir John Colborne* to replace Maitland would lead to further victories. They argued that opposition was legitimate; it was neither disloyal nor discourteous to the crown to criticize its representative in the province. Copying the words used in 1826 by John Cam Hobhouse in the House of Commons, John Rolph referred to himself as one of “His Majesty’s faithful opposition.” Hope was expressed that the new lieutenant governor would choose his advisers from the reform group that had a majority in the assembly. The assembly might then bring the lieutenant governor’s advisers to account, which it had been unable to do while Maitland was in office. It was clear, however, that the British constitutional concept of responsible advisers was, for Upper Canada, not acceptable to the imperial authorities. The reform opposition’s disappointment is evident in the assembly’s response to the throne speech in January 1829, which noted that Colborne was “surrounded” by the same advisers who “so deeply wounded the feelings and injured the best interests of the Country.” Earlier, one of Maitland’s harshest critics, William Lyon Mackenzie, had expressed a similar sentiment. Maitland, he said in 1824, was a religious, humane, and peaceable man “and if his administration had hitherto produced little good to the country, it may be it was not his fault, but the fault of those about him who abused his confidence.”

Maitland had been sworn in as lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia on 29 Nov. 1828, with the added responsibility of commander-in-chief of the forces in the Atlantic region. Initially he was a far less controversial figure than he had been in Upper Canada. In May 1829 George Couper, Sir James Kempt’s military secretary, confided in Lord Dalhousie that Maitland’s apparent apathy as lieutenant governor was generally condemned, but that he was popular as a man. Certainly his strongly moral conduct had an impact on Halifax’s society. By insisting on walking to church, he effectively ended the garrison parades on Sunday, the city’s major social event, and he publicly denounced the open market that day. In October his recurrent ill health forced him to move to the West Indies, leaving Michael Wallace* as provincial administrator.

Maitland resumed duty in June 1830, shortly after the rupture between the Council and the assembly over matters of revenue [see Enos Collins*]. He clearly understood that the dispute was exacerbated by the manœuvring for the chief justiceship of Solicitor General Samuel George William Archibald* and Judge Brenton Halliburton (whom Maitland favoured). Maitland’s inaction on the revenue issue, pending instruction from the Colonial Office, was resolved by the death of King George IV, which necessitated calling the “Brandy Election” that fall.

In the ensuing political calm of 1831, Maitland’s manner of governing drew the early editorial criticism of Joseph Howe*, the spokesman of the emerging reform movement, who openly derided Maitland’s shortcomings, including his lack of any gubernatorial achievement and his irresolution in handling the revenue crisis of the previous years. Maitland attempted to maintain a non-partisan position in the ongoing debates in 1831–32 over contentious matters of sectarian education; in 1832 he claimed some responsibility for the settlement reached for Pictou Academy [see Thomas McCulloch*]. In dealing with immigration and settlement, one of his major interests in Upper Canada, Maitland could act decisively. In 1831 he had lands laid out in Cape Breton at crown expense so that the 4,000 immigrants expected that year could be legally placed and systematically settled.

In October 1832 Maitland went to England on leave, presumably because of his health, and the government was placed in charge of Thomas Nickleson Jeffery*. Though he continued to conduct official correspondence from England, he never returned to North America and he was succeeded in Nova Scotia by Sir Colin Campbell* in July 1834.

For two years (1834–36) he was commander-in-chief of the British army in Madras; in 1843, at the age of 67, he became governor and commander-in-chief of the Cape Colony (Republic of South Africa). Arriving there early in 1844, he was well received by all elements of the colony’s society (the heads of missionary societies were particularly impressed by his Christian devoutness and humanitarian interests). But by 1846 few considered him capable of dealing effectively with the difficult problems developing in relations with the Kaffir (Xhosa) and Griqua peoples and the Boers on the colony’s frontiers. In the opinion of Lord Grey, the colonial secretary, Maitland had never been “a man of any great ability” and should have been retired. James Stephen, the colonial under-secretary, clearly recognized in 1846 that Maitland’s administrative weakness was masked by the efficiency of his secretary, who wrote many of his dispatches. Promoted general in November 1846, several months after the outbreak of the Kaffir war, Maitland was replaced early in 1847, being considered too old and ineffective. He returned to London, where he lived in retirement until his death on 30 May 1854. In 1851, along with Sir John Colborne, he had been a pall-bearer at the funeral of the Duke of Wellington. The following year he was made a gcb.

As lieutenant governor of Upper Canada, the colony with which he has been chiefly identified, Maitland had the true interests of the province at heart. He worked with vigour and determination towards its growth and economic development. But in the view of his critics he merited censure. His administration was called a “reign of terror” by John Rolph; he had oppressed and harassed the people of the province. Such expressions were part of the inflammatory and highly personalized rhetoric of the political scene in Upper Canada. On his part Maitland was as guilty of over-reaction as his critics. With his military background and his conservative convictions he stood resolutely against those he considered his inferiors and who were thought to be enemies of the imperial connection. Despite his position during the alien issue, he could never see himself as partisan. In the British constitutional system, unlike that of the United States, there had to be an executive that stood above faction. His only duty, he said in 1821, was “to fulfil the wishes and expectations of my Sovereign.” The assembly had a role in government, in achieving the checks and balances as defined in the British constitution, but Maitland could never accept the concept of dominance by an elected assembly.

The principles to which he held were not uncommon in the days of the Napoleonic period in Britain, when democratic ideas, it was feared, would lead to revolution, chaos, and mob rule, as they had in France. Maitland saw the same danger arising in Upper Canada, because of its proximity to the United States and the large American-born element in its population. In his administration he reflected the same fears as those of his native Upper Canadian advisers. He was as intransigent in his views as his critics, failing to appreciate that opposition was not necessarily disloyalty, and that the liberal winds blowing in Britain, which would bring about the Reform Act of 1832, would mark his authoritarian and hierarchical view of society as too inflexible. During his administration of Upper Canada the struggle between resolute and often rigid personalities forced the province to engage in organized political discussion to an extent unknown in the pre-Gourlay days. Debate and confrontation fostered the political education of the province through increased interest and participation in the political process. Upper Canadians had, as Gourlay wished, become activated.

[Maitland’s official correspondence, most of it in PRO, CO 42/361–90 and PAC, MG 11, [CO 217] Nova Scotia A, 169–79, is the main source of information on his life and career. There are some useful items in the AO, in the Macaulay papers (MS 78) and the Strachan papers (MS 35), and at the MTL in the papers of William Dummer Powell. A number of the important state papers are reproduced in Docs. relating to constitutional hist., 1819–28 (Doughty and Story). The only full treatment of Maitland is F. M. Quealey’s thesis, “The administration of Sir Peregrine Maitland, lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada, 1818–1829” (phd thesis, 2v., Univ. of Toronto, 1968).

A copy of Sir William John Newton’s portrait of Maitland is in the William Fehr Collection at The Castle, Cape Town, South Africa; a water-colour portrait is at the MTL. h.b.]

AO, MU 2104, 1822, no.4. Hampshire Record Office (Winchester, Eng.), Longparish, reg. of baptisms, 29 July 1777. Gentleman’s Magazine, July–December 1854: 300. “Journals of Legislative Assembly of U.C.,” AO Report, 1913: 269. Ramsay, Dalhousie journals (Whitelaw), 1: 131, 139, 141; 2: 25, 72. Town of York, 1815–34 (Firth). Colonial Advocate, 8 July 1824. Kingston Chronicle, 15 Dec. 1826; 2 Aug., 1 Nov. 1828; 24 Jan. 1829. U.E. Loyalist (York [Toronto]), 10 March 1826. Upper Canada Gazette, “Extra,” 13 April 1825; 23 Feb.–30 March, 4 Nov., 5 Dec. 1826; 30 July 1828. Upper Canada Herald (Kingston, [Ont.]), 26 Dec. 1826; 9 Oct. 1827; 29 Jan., 26 Feb., 4, 11 March, 30 July 1828; 28 Jan. 1829. John and J. B. Burke, A genealogical and heraldic dictionary of the landed gentry of Great Britain and Ireland (3v., London, 1849). “Calendar of the Dalhousie papers,” PAC Report, 1938: 9–12, 130. DNB. Hart’s army list, 1853. Morgan, Sketches of celebrated Canadians, 244–45. “Nova Scotia state papers,” PAC Report, 1947: 77–184. Nova Scotia vital statistics from newspapers, 1813–1822, comp. T. A. Punch (Halifax, 1978), no.1957; 1829–34, comp. J. M. Holder and G. L. Hubley (1982), nos.785, 1159, 1794, 3076. D. B. Read, The lieutenant-governors of Upper Canada and Ontario, 1792–1899 (Toronto, 1900), 117–18. “State papers – U.C.,” PAC Report, 1900, 1901, 1943. A. N. Bethune, Memoir of the Right Reverend John Strachan . . . (Toronto, 1870). Peter Burroughs, The Canadian crisis and British colonial policy, 1828–1841 (London, 1972), 28–42. Cowdell, Land policies of U.C., 123. Craig, Upper Canada. J. S. Galbraith, Reluctant empire: British policy on the South African frontier, 1834–1854 (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1963). F. W. Hamilton, The origin and history of the First or Grenadier Guards . . . (3v., London, 1874), 3: 10, 61. J. S. Moir, Church and state in Canada West: three studies in denominationalism and nationalism, 1841–1867 (Toronto, 1959). Scadding, Toronto of old (1873; ed. Armstrong, 1966). G. McC. Theal, History of South Africa, from 1795–1872 (5v., London, [1915–26]; repr. 1964), 2: 232; 3: 39–40. Peter Burroughs, “The administration of crown lands in Nova Scotia, 1827–1848,” N.S. Hist. Soc., Coll., 35 (1966): 98–99. E. A. Cruikshank, “Charles Lennox, the fourth Duke of Richmond,” OH, 24 (1927): 323–51. B. C. U. Cuthbertson, “Place, politics and the brandy election of 1830,” N.S. Hist. Soc., Coll., 41 (1982): 16–17. J. B. Robinson, “Early governors: reminiscences by the Hon. John Beverley Robinson,” Daily Mail and Empire (Toronto), 23 March 1895: 10. “Unveiling cairn at governor’s cottage and tablet at ossuary at Niagara,” Mail and Empire, 5 Oct. 1934: 12. Fred Williams, “They remember – in Lundy’s Lane,” Mail and Empire, 5 Oct. 1934: 8.

Cite This Article

Hartwell Bowsfield, “MAITLAND, Sir PEREGRINE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/maitland_peregrine_8E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/maitland_peregrine_8E.html |

| Author of Article: | Hartwell Bowsfield |

| Title of Article: | MAITLAND, Sir PEREGRINE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1985 |

| Access Date: | March 30, 2025 |