Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

CHOMEDEY DE MAISONNEUVE, PAUL DE, gentleman, officer, member of the Société Notre-Dame de Montréal, co-founder of Ville-Marie, first governor of the island of Montreal; b. Neuville-sur-Vanne in the province of Champagne and baptized there 15 Feb. 1612; d. 1676 in Paris.

Paul de Chomedey was the son of Louis de Chomedey, seigneur of Chavane, Germenoy-en-Brie, and other places, and of his second wife Marie de Thomelin; the latter was the daughter of the aristocrat Jean de Thomelin, a king’s councillor and a treasurer of France in the generality of Champagne, and of Ambroise d’Aulquoy. He had as godfathers Paul Janson, a lieutenant in the bailiff’s court at Villemort, and Gabriel de Campan; his godmother was Jeanne de Chabert.

The arms of Paul de Chomedey’s grandfather, Hierosme, were “or, three flames gules.” They were handed down in the direct line to Paul de Chomedey, the eldest son of Louis, himself the son of Hierosme.

Paul de Chomedey grew up in the manor-house at Neuville-sur-Vanne, not far from the Maisonneuve fief, which his father acquired in 1614. He had two sisters and one brother. Louise, the eldest of the family, whose certificate of baptism has not been located, was later to become Mother Louise de Sainte-Marie of the Congrégation Notre-Dame at Troyes. The date of her death is not known; we do know, however, that she survived her brother Paul, as is attested by the legacy that he made to her in his will dated 8 Sept. 1676. Odard, Paul’s younger brother, was born in 1614 and died at the age of 33. Jacqueline, the youngest of the family, was born in 1618. In 1638 she married François Bouvot (not Bonnot) de Chevilly (not Chuly), with whom she had two daughters. One of them was later to assert her rights as the sole heiress of her uncle Paul. Jacqueline de Chomedey de Chevilly, who gave such effective protection to Marguerite Bourgeoys before the latter’s departure for Canada in 1653, met a sad end a short time afterwards. She died in 1655, assassinated by a sworn enemy of the family. Four years earlier her husband had suffered the same fate, by the same hand.

Paul de Chomedey’s military career began early, as was customary during this period. Concerning the enlistment of the eldest of the Chomedeys, and also the incidents in his life as a young soldier winning his laurels, there is a regrettable dearth of authentic documents. Leymarie admits that he was not able to find any document relating to him for the period between 2 June 1624 and 1640. Our only resort must therefore be to works in which the assertions are not at first-hand.

François Dollier* de Casson, in his Histoire du Montréal, briefly described Paul de Chomedey’s youth: Providence, which “had caused him to take up the profession of war in Holland at the age of 13, in order to give him more experience, had taken care to preserve his heart in purity in the midst of these heretical countries and among the freethinkers to be found there.” He added that, “in order not to be obliged to go and seek distraction in the company of evil men, he learned to pluck the lute.”

M. Dollier is almost the only historian to give details on M. de Maisonneuve’s disposition, tastes, and unique character. He also offers an insight into the circumstances that determined Maisonneuve’s plans. But we must give due weight, in all this, to an important statement by the Sulpician narrator. He warned his readers in the first lines of his Histoire “that they must not expect . . . that it will not contain a few slight errors in dates and times, or that . . . I shall not omit a very great number of such . . . , because the religion of these pious people . . . has never been able to tolerate anything unusual being published by booksellers concerning what has been done here, so much so that I am constrained today, when I have no authentic evidence of the same, to leave . . . shrouded in darkness what might deservedly be exposed to the brightest daylight.” He also said, speaking of his sources, that they were all oral, and that he would restrict himself to recounting the gist of the history of Montreal.

M. Dollier, as a member of the Compagnie de Saint-Sulpice, which was so intimately linked through its founder Jean-Jacques Olier to the history of the early days of Montreal, could not help being deeply interested in the vocation of the first governor of Ville-Marie. He wrote: “The time having arrived when Providence wanted to employ him upon its work, it so increased in him the fear of divine retribution that to avoid this perverted world which he knew, he desired to go and serve his God, through his profession, in several very remote countries. One day, turning over these thoughts in his mind, he providentially came upon . . . a Relation from this country [New France] in which mention was made of Father Charles Lalemant, who had returned from Canada some time before . . . ; he resolved to go and see the Father . . . to whom he revealed his inmost intention; the Father, judging that this gentleman was exactly the person that the Sulpicians of Montreal needed, recommended him to M. de la Doversière.”

Jérôme Le Royer de La Dauversière, who was to impart a new direction to Paul de Chomedey’s life, was a humble tax-collector in the little town of La Flèche, in the province of Anjou. In fact, he was one of the great servants of God in that period, an inspired soul, an architect of vast projects of a charitable, missionary, civilizing, or devotional nature. He was, moreover, merely one representative of the wave of mysticism that originated in Spain in the 16th century and invaded France in the 17th, numbering among its significant results the founding of the Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement, which played such an important role in France even after the interdiction of 1660.

Born on 18 March 1597 at La Flèche (department of the Sarthe), he was the younger son of Jérôme Le Royer, first seigneur of La Dauversière, and of Renée (or Marie) Oudin. His family originated in Brittany.

Jérôme was one of the first pupils of the Collège at La Flèche, founded in 1604 by Henri IV and operated by the Jesuits. There he met Father Charles Lalemant, who had entered the Society of Jesus in 1607 and was ten years his senior, and Father Paul Le Jeune, who had entered in 1613. In addition to the philosopher René Descartes, he had as fellow-students several of the great missionaries of New France, such as François Ragueneau [see Paul Ragueneau], Claude Quentin, Charles Du Marché, and Jacques Buteux. With them, he heard Father Énemond Massé, in 1614, speak of the Acadian missions, recently abandoned as a result of the English conquest.

On his father’s death during the summer of 1618, Jérôme inherited the name and fief of La Dauversière, as well as the office of receiver of the taille at La Flèche. In 1620 he married Jeanne de Baugé, with whom he had six children. Possessed of a firm piety and manifest zeal for good works, he soon became, with his elder brother Joseph, the promoter and organizer of the charitable undertakings in his small town. It is said that it was a supernatural vision that led him to found an institute of Hospitallers dedicated to St. Joseph. This vision would have occurred in 1632 or the beginning of 1633.

The second supernatural revelation that M. de La Dauversière is stated to have had can be set in the year 1635 or 1636. According to the text found in the Véritables motifs of the Société Notre-Dame de Montréal, printed in 1643, the “establishment of Montreal was conceived by a man of virtue whom it pleased divine goodness to inspire, seven or eight years previously, with the desire of working for the Indians of New France, of whom he had no special knowledge before, and despite any repugnance that he might have felt for the task, as being beyond his strength, contrary to his status, and harmful to his family. Finally, several times urged on and enlightened by inner visions, which showed him in their reality the places, things and persons that he was to utilize . . . [and] encouraged inwardly to undertake it as a conspicuous service that God was asking of him, he responded like Samuel to his master’s summons.”

In February 1639, on the advice of Father François Chauveau, a Jesuit at the Collège of La Flèche, M. de La Dauversière went to Paris with Pierre Chevrier, Baron de Fancamp, who had long been won over to the Montreal cause, to form a society capable of carrying through an undertaking of such magnitude: the founding of a missionary city in distant Canada. Then, at the end of that month, occurred the meeting with Abbé Jean-Jacques Olier, a young priest of 31 who, since 1636, had wanted to work for the conversion of unbelievers. He did not yet know, however, in what country. On this point we have his own testimony.

M. de La Dauversière and M. Olier met in the gallery painted by Simon Vouet at the entrance to Chancellor Pierre Séguier’s sumptuous dwelling in Paris. In this connection mention is made, erroneously, of an interview at the Château de Meudon, the abandoned residence of Charles de Lorraine, Duc de Guise, who had been living in Italy since 1631. For two hours they talked. Agreement was reached on the main features of the plan: the acquisition of the island of Montreal, the property of Jean de Lauson, an intendant in Dauphiné and the future governor of New France, and also the founding of a society of gentlemen and ladies whose rapid recruitment certainly did not seem impossible. M. Olier was already prepared to answer for the consent of the Baron Gaston de Renty, one of the great philanthropists of the 17th century, and the superior of the famous Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement of which both de La Dauversière and Olier were members. M. Olier would likewise invite two more of his friends to enter the Société de Montréal.

Thought soon had to be given to finding a young leader, endowed with all the qualities necessary for directing this undertaking, which partook of both colonization and evangelization. One day Father Charles Lalemant, whom M. de La Dauversière consulted continually about the numerous requirements of his venture, said to him, after hearing once more his lamentations on the subject of this yet-to-be-discovered leader for the first Montreal contingent: “I know a worthy gentleman of Champagne named M. de Maison-neufve, who has such and such qualities; he might well meet your needs.” M. de La Dauversière lost no time in having a conversation with Paul de Chomedey, to whom he entrusted with absolute confidence the direction of his overseas foundation. M. de Maisonneuve would be granted powers in Canada corresponding to the rights and duties of the Société Notre-Dame de Montréal’s directors in France. The latter would recruit, finance, and assist in every way the little colony being formed. M. de Maisonneuve thus became one of the principal “Associates” of Montreal, to the great joy of Olier and de Fancamp. A “gentleman of virtue and courage,” as the anonymous authors of the Véritables motifs called him, he soon went to La Rochelle, the place of the settlers’ departure.

On 9 May 1641 two ships left the port of La Rochelle, carrying out to sea towards New France the main group of the Montreal settlers. In one of the vessels were M. de Maisonneuve with 25 men and a secular priest intended for the Ursulines; in the other were 13 men, including the Jesuit Father Jacques de La Place, and nurse Jeanne Mance, the contingent’s bursar, who would become the settlement’s co-founder. The rest of the contingent (ten men) had left the port of Dieppe some weeks before. Three other women were on board: two of the workmen had refused to embark without their wives, and a young local girl had “violently” pushed her way into the ship, resolved to go and serve God by serving Indigenous peoples.

After a crossing of about three months, the ship bearing Jeanne Mance and Father de La Place reached Quebec without mishap. Dollier de Casson speaks of 8 August, a very likely arrival date. The ship bringing M. de Maisonneuve was less fortunate; it “met with such furious storms that it was obliged to put into port three times” in France. In these circumstances M. de Maisonneuve lost three or four men and his surgeon.

At what date did M. de Maisonneuve arrive at Tadoussac? Obviously very late – “so late,” said the 1641 Relation, that the first arrivals would be quite unable to establish themselves at Montreal before the following spring. Dollier de Casson favoured 20 August, an unlikely date, for only 12 days would have passed since Jeanne Mance had set foot on shore. She was full of concern, even of anxiety, since she heard it said on all sides that the arrival of ships from France was becoming impossible at that season of the year. The only document that refers to Maisonneuve’s presence in Canada in 1641 is a certificate of baptism dated 20 Sept. 1641, inserted in the register of baptisms at Sillery, that has no indication of place (but in the margin of the document is the word Tadoussac). M. de Maisonneuve appears there as the godfather and Jeanne Mance as the godmother of a little Indigenous girl baptized by Father Paul Le Jeune, just before the latter’s departure for France by the last ship. Can one conclude from this that the baptism took place at Tadoussac and not at Sillery, and that the date 20 Sept. 1641 might be the exact date of M. de Maisonneuve’s arrival on Canadian soil? As far as Jeanne Mance is concerned, we can understand that she may have hastened to Tadoussac to inform the pioneers’ leader of the opposition manifested at Quebec against the plan to set up a small colony on the island of Montreal. “Foolhardy undertaking!” was the general outcry.

Paul de Chomedey was not upset by the hostility evidenced by the inhabitants of Quebec. Duly warned of the situation, he confronted his opponents. He was a wise man, possessed of unusual prudence, but also a resolute soldier. From the time of his first interview with Governor Huault de Montmagny he adhered to his decision to go up to Montreal the following spring since the season was now too far advanced. A new move was attempted shortly afterwards by the governor and all the notables of Quebec. M. de Maisonneuve was offered the Île d’Orléans in exchange for the island of Montreal, where he might be more easily within reach of help in case of attack. And it was then that Paul de Chomedey uttered the proud words that Dollier de Casson has preserved for us: “Sir, what you are saying to me would be good if I had been sent to deliberate and choose a post; but having been instructed to go to Montreal by the Company that sends me, my honour is at stake, and you will agree that I must go up there to start a colony, even if all the trees on that island were to change into so many Iroquois.” Faced with this inflexibility, displayed with such dignity, all were obliged to yield. For his part M. de Montmagny, as well as Father Barthélemy Vimont, the Jesuits’ superior, undertook to go personally to the island of Montreal in October, together with several “persons, well versed in knowledge of the country,” to choose the most favourable spot for the creation of this new post. It was impossible for M. de Maisonneuve to accompany them, for he was busy supervising the unloading of the ships and setting his men to work. Hence his name does not appear in the paragraph of the Relations recounting the little trip made on 15 Oct. 1641.

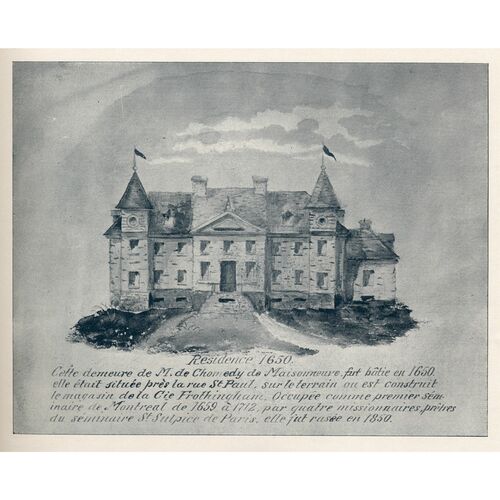

In addition to the tasks we have just mentioned, M. de Maisonneuve was acutely concerned with the question of the settlers’ housing. It was late in the season. He could see no lodging suitable for the 56 (perhaps 58) people who made up the little colony of Montreal. All the immediate difficulties, however, were resolved after a visit to the seigneury of Sainte-Foy, in the neighbourhood of Quebec, where a rich septuagenarian, Pierre de Puiseaux de Montrénault, expressed an earnest desire to receive M. de Maisonneuve. As soon as M. de Puiseaux had made M. de Maisonneuve’s acquaintance and heard about the apostolic and civilizing mission being undertaken at Montreal, he asked to enter the Société Notre-Dame, wishing to follow the post’s co-founders. As proof of his sincere intentions he offered, as an outright gift, his two seigneuries of Sainte-Foy and Saint-Michel (at Sillery). In November 1641 M. de Maisonneuve accepted the kindly old man’s offer, and both then decided on the best use to be made of these rich seigneuries. The Sainte-Foy house, surrounded by fine oaks, could serve as a building-yard and a shelter for the majority of the Montreal men; the Saint-Michel house would be assigned to Maisonneuve, de Puiseaux, Jeanne Mance, Mme de Chauvigny de La Peltrie, who had hitherto been its tenant, and several other people. A few of the contingent’s men would also be housed there to do joinery work.

An unfortunate incident occurred in January 1642, bringing the governor-general and the local governor into conflict. One of those thorny questions as to the extent or limitations of the power of each arose for the first time in Canada, where they were to become very frequent. On 24 January, the eve of the conversion of St. Paul, M. de Maisonneuve’s patron saint, the Montreal men had received some gunpowder from Jeanne Mance, the contingent’s bursar, so that a salvo of artillery could be fired at dawn on the twenty-fifth to mark M. de Maisonneuve’s anniversary. The noise of the detonations was heard as far away as Quebec. M. de Montmagny was offended because his consent to the firing of cannon in this way had not been sought. The gunner for the occasion was arrested and interned; he was Jean Gorry, a Breton from Pont-Aven, who was employed at Quebec by M. de Maisonneuve as a ship’s master. Legal action followed. M. de Montmagny had finally to set Jean Gorry free, having really exceeded his authority. M. de Maisonneuve was able to show a letter from Louis XIII which authorized the Montreal contingent to possess artillery and to fire cannon. During these difficult days M. de Maisonneuve displayed moderation and endurance. He let the storm pass. But he took his revenge by helping the victim of the incident. He even went so far as to increase his wages.

M. de Montmagny endeavoured subsequently to atone for the extravagance of his behaviour. “On the seventeenth of May of the present year, 1642, Monsieur the Governor placed the sieur de Maison-neufve in possession of the Island, in the name of the Gentlemen of Mont-real, in order to commence the first buildings thereon. Reverend Father Vimont had the Veni Creator chanted, said Holy Mass, and exposed the Blessed Sacrament, to obtain from Heaven a happy beginning for the undertaking. Immediately afterwards, the men were set to work, and a redout was made of strong palisades for protection against enemies.” Father Vimont, the superior of the Jesuit missions in Canada, to whom must be attributed the substance of this text, taken from the Relation of 1642, was an eye witness of, and took part in, these ceremonies.

Among the incidents pertaining to the founding of Montreal, one action of M. de Maisonneuve remains to be noted. The governor of Montreal, as we have seen, had set his men to work as soon as the civil and religious ceremonies were completed. Several trees had to be felled before the settlers could erect the stronghold of thick stakes. Sister Marie Morin* tells us that the governor wished to fell the first tree himself.

Father Vimont, who celebrated the first high mass sung at Montreal on Sunday 18 May 1642, delivered an address in which he foretold, in a way, the future greatness of the new town.

The first baptism took place in the month of July. “On the twenty-eighth of July, a small party of Algonquins, who were passing that way, stopped there for several days. The Captain brought his son, aged about four years, to be Baptized. Father Joseph Poncet made him a Christian, and the sieur de Maison-neufve and Mademoiselle Mance named him Joseph on behalf of the Gentlemen and Ladies of Nostre Dame de Mont-real. This is the first fruit that this Island has borne for Paradise; it will not be the last. Crescat in mille millia.”

In the month of August the arrival of the French ships caused excitement among the Montrealers. They wondered what news they were going to receive from France. Pierre Legardeur de Repentigny landed one morning on the shores of Montreal. He brought with him the 12 settlers of the second contingent, a great quantity of provisions, sacred ornaments, and munitions. He informed M. de Maisonneuve and Mlle Mance that the Dessein de Montréal, written by M. de La Dauversière at Mlle Mance’s suggestion and distributed in devout and influential circles, had noticeably increased the number of Associates in France. “About thirty-five persons of condition have joined together . . . in the Church of Notre Dame at Paris,” and “consecrated the Island of Montreal to the Holy Family . . . , under the special protection of the Blessed Virgin.” The Montrealers gave free rein to their joy a few days later. The feast of the Assumption on 15 August was celebrated with pomp. At this first great festival of Notre-Dame de Montréal, “the thunder of the cannons caused the whole Island to reëcho.”

The year 1642, however, came to a dramatic close. The settlers’ safety was seriously threatened when the St. Lawrence river overflowed and a flood became imminent. M. de Maisonneuve distinguished himself by his self-possession and especially by his lively faith. After consultation with the chaplains, Fathers Poncet and Du Peron, he promised, if the waters that were already surging against the gates of the fort subsided without causing any serious damage, to walk with a cross on his shoulders to the top of Mount Royal, and there to set it up. He put his promise in writing, had it read publicly, and then he went and placed a cross, at whose foot was the written statement, on the bank of the roaring river: “the waters, having stopped a little while at the threshold of the gate, without swelling further, subsided by degrees, put the inhabitants out of danger, and set the Captain [M. de Maisonneuve] to the fulfillment of his promise.”

The Iroquois (Haudenosaunee), not knowing of the establishment of a post at Montreal, did not appear until the summer of 1643. But from then on they used the tactic at which they were past masters: war by ambush. On the one day of 9 June 1643 they took six prisoners from among the Montrealers, only one of whom was to escape after a gruelling captivity.

A difficult life, full of unceasing, exhausting struggles, had now begun. It was to continue for a quarter of a century. The victims fell in great numbers, but prepared each morning for the supreme sacrifice by receiving the Eucharist. In the Montreal that, in 1643, was compared to the early church, they paid the ransom for all. And always M. de Maisonneuve stood out as the incomparable leader of this handful of men and women. He also showed himself a skilful organiser. The Véritables motifs, written during the summer of 1643, offer us a picture of the little post shortly after its founding: “The building consists of a fort for defence, a hospital for the sick, and a lodging already capable of housing 70 persons who live there . . . with two Jesuit Fathers who are like pastors to them; there is a chapel there that serves as a parish, under the title of Notre Dame to whom, with the island and the town which is designated by the name of Ville Marie, it is dedicated. The inhabitants live for the most part communally, as in a sort of inn; others live on their private means, but all live in Jesus Christ, with one heart and soul.”

In July, on the day after the arrival of the first ships from France, M. de Montmagny went up to Ville-Marie. He had received a personal letter from Louis XIII, enjoining him to give his most special protection to the little settlement at Montreal. He also announced that the king was presenting the Associates of Montreal with a 350-ton ship called the Notre-Dame, which would cross the ocean each year. The Montrealers could also expect to receive effects of all kinds, and even, it was said, sums of money intended by an “unknown benefactress” for the hospital’s construction and for Mlle Mance. Patience was necessary, however, for the third Montreal contingent would arrive only in September. It would be led by a gentleman from Champagne, Louis d’Ailleboust de Coulonge et d’Argentenay, a talented military engineer; he was coming to settle at Montreal with his wife, Barbe de Boullongne, who would be accompanied by her sister, Philippe or Philippine-Gertrude de Boullongne. All three, on Father Charles Lalemant’s advice, had become members of the Société Notre-Dame. Two months later, the rejoicing inhabitants of Ville-Marie thronged around the new settlers. Everyone perceived that the Associates in France were truly lavishing gifts upon their remote little outpost.

But that same autumn there were some departures as well. M. de Puiseaux, paralysed, “his brain weakened by his old age,” asked for the return of his assets, to go to France for treatment. M. de Maisonneuve, generous and understanding, agreed to this withdrawal. He also promised to recommend the worthy old man to the Associates of Montreal. Mme de La Peltrie and her companion, Charlotte Barré, likewise left. Mme de La Peltrie was recalled to Quebec by the Jesuits and by her charitable works, which could not survive without her help. She set off without too much anxiety, knowing that Mlle Mance would be sustained by the distinguished ladies, Mme d’Ailleboust and her sister, who had just arrived.

“Frenchmen,” wrote Dollier de Casson, “were tired of seeing themselves insulted every day by the Iroquois.” Anger had been building up in their hearts since the deaths of their fellow-workers the preceding year. They continually begged M. de Maisonneuve to allow them to match themselves against their enemies, who watched them unremittingly from the deep concealment of the forest. M. de Maisonneuve refused; he knew that they were unfamiliar with skirmishing and considered them not sufficiently numerous to face 100 or perhaps 200 Iroquois. They obeyed, but “our fiery Frenchmen” eventually concluded that “M. de Maison-neufve was afraid to expose himself.” On 30 March 1644 the watch-dogs, which had been brought from France to locate the Iroquois, started, under the leadership of a bitch named Pilote, “to cry out and howl with all their might, looking towards the direction where they sensed the enemy.” The settlers ran to find M. de Maisonneuve: “Sir, the enemies are in the wood in such and such a direction, shall we never go and find them?” To which the governor replied: “Yes, you shall see them. Get ready right away to march, but see that you are as brave as you make out to be – I shall be leading you.” Once in the wood the settlers, who numbered 30, perceived 200 Iroquois, well placed in various ambushes. With seven Iroquois for every settler, the odds were not with them. The French did the best they could while their bullets lasted, but when their powder ran out they had to beat a retreat. M. de Maisonneuve directed the expedition successfully. He withdrew only when he saw that the wounded were already at a distance and well guarded. The settlers were no sooner out of the wood than they were stricken with panic and bolted towards the fort, leaving M. de Maisonneuve alone and far in their rear. One of the Iroquois chiefs quickly overtook him; M. de Maisonneuve immediately fired at him. The Iroquois clawed at his throat, and at once he discharged his second pistol and laid his assailant dead at his feet. Thunderstruck, the enemy hesitated a moment, then rushed towards their chief; one of them loaded him on his shoulders, and they all plunged hastily into the wood. When M. de Maisonneuve entered the fort, the settlers flocked about him, showed their joy at his victory, praised his unusual bravery, and swore that in future they would take good care not to expose his life in such a way.

M. de Maisonneuve left for France in the autumn of 1645, having received news of his father’s death. On leaving Ville-Marie he had entrusted his powers to Louis d’Ailleboust. On 9 Jan. 1646 we find him taking an “oath of fealty” and doing homage for the Maisonneuve fief, of which he had become the owner. He returned to Quebec on 20 September, after a year’s stay in France, but on landing he found an urgent letter from M. de La Dauversière, requesting him to return to Europe with the least possible delay. Events concerning him personally, and others related to the affairs of Montreal, required his presence in France. M. de Maisonneuve was therefore unable to visit the Montrealers before sailing again, for in October he had to attend the meetings of the Communauté des Habitants, founded on 14 Jan. 1645. At this time great changes had taken place with respect to the fur trade. The Compagnie des Cent-Associés had ceded “to the communauté des habitants in Canada . . . the right to trade in pelts, with the exception of the trade at Miscou, at Cap-Breton and in Acadia, while reserving to itself, in addition, the feudal and seigneurial dues collected in the country. In return the communauté undertook to meet the costs of the colony’s administration, religious worship and defence, to send 20 settlers to Canada each year, and to pay the compagnie de la Nouvelle-France 1,000 beavers annually.”

The meetings of the council of the Communauté des Habitants were often stormy. The Journal des Jésuites reported that “all those of the Council make strenuous efforts to augment their own pay and to requite their own services, which resulted in such confusion as was disgraceful. But, as Monsieur de Maisonneuve had not consented thereto, none of these gratuities were subscribed to.” On 31 Oct. 1646, together with Robert Giffard, M. de Maisonneuve again sailed for France.

Although the governor of Montreal, when he reached his destination, had to concern himself with his personal interests, he certainly did not fail to attend equally to the proper conduct of the affairs of Montreal. There was much discussion, with M. de La Dauversière and on occasion with the other Associates, about the fur trade and the most recent incidents that had occurred before he left Canada. M. de La Dauversière endorsed M. de Maisonneuve’s leadership.

The appointment of a successor to M. de Montmagny, who was to be recalled to France, was discussed with M. de Maisonneuve. The Associates offered him this high office. He refused, and proposed instead Louis d’Ailleboust. He took care not to mention his refusal, when on his return to Montreal in the summer of 1647 he warned M. d’Ailleboust that the latter had to go to France, that he would be appointed governor of New France there, and that he would return the following year with his commission.

M. de Maisonneuve had brought back some orders from the Société de Montréal concerning the distribution of the lands under his administration, a measure that was now necessary. The first grantee, Pierre Gadoys, signed his deed of grant 4 Jan. 1648. At the bottom of the document, which was written entirely in M. de Maisonneuve’s own hand, one reads: “Acceptance of the said grant made before the notary Jean de Saint-Père.” As Benjamin Sulte* stated: “It was from 1654 that grants of land were given in sufficient number to encourage the hope that the island of Montreal would finally be settled permanently.” “So long as M. de Maisonneuve was the governor, none but he made land grants, and the number of deeds issued by him was 123. It is evident, however, that we lack some of them, which will be found either complete, or mentioned in other documents.” Is it not appropriate to stress in this regard the profound unselfishness of the Associates of Montreal, who had promised, from the first days of the town, to take, in this immense expanse of 250,000 acres, only the land necessary for their living? “The island of Montreal was therefore reserved entirely for real and genuine colonization,” remarked Camille Bertrand. And he added that “M. de Maisonneuve never possessed a foot of ground, although he was resident governor for 23 years. Neither did Jeanne Mance ever own any land. It was as the hospital’s director that she received some pieces of land for the support of the poor in the Hôtel-Dieu.” M. d’Ailleboust was the sole, although quite legitimate exception, since he was settling at Montreal in 1643.

On 2 March 1648 M. d’Ailleboust had been appointed governor of New France for three years. He landed at Quebec 20 Aug. 1648, bringing with him his nephew, Charles-Joseph d’Ailleboust Des Muceaux, a brave career officer. The new governor moved soon after into the Château Saint-Louis with his wife. His sister-in-law, around the same date, joined the Ursulines.

Heart-rending news from Paris reached Mlle Mance in 1649. First, Father Rapine de Boisvert, a Recollet who had served as intermediary between the “unknown benefactress” and Mlle Mance, had died in December 1648; then the Société Notre-Dame de Montréal, which the death of the Baron de Renty and the withdrawal of a number of others had unsettled and weakened, was no longer showing any sign of life; and above all the mortal illness that afflicted M. de La Dauversière, the creator of the evangelizing undertaking at Ville-Marie and its guiding spirit, might put an end to the entire Montreal venture. These “three bludgeon strokes,” wrote Dollier de Casson, forced Mlle Mance to sail at once for France. In truth, peril reigned everywhere, in old France as in the new. Shortly after Mlle Mance’s departure, news arrived of the martyrdom of Fathers Jean de Brébeuf and Gabriel Lalemant. Next came the almost total annihilation of the Huron (Wendat), small groups of whom arrived at Ville-Marie each day seeking refuge. Everyone could foresee then the danger that would soon threaten Ville-Marie, for once the Huron were conquered the Iroquois would set their sights on the Montrealers. They were already swearing to destroy everything in that tiny, almost defenceless post; “ceaselessly,” recorded M. Dollier, “we had them pressing upon us, there is not a month in this summer when our book of the dead has not been stained in red letters by the hands of the Iroquois.” Mlle Mance’s return, in the autumn of 1650, brought a little solace to the beleaguered. The hospital’s director had successfully completed her mission. The Société Notre-Dame de Montréal would be restored to life, thanks to the complete support of M. Olier, who had agreed to direct it thenceforth. The Montrealers’ distress had moved him. Moreover M. de La Dauversière, who had recovered, was also actively promoting the undertaking. And the “unknown benefactress,” whom Jeanne Mance had often visited, remained the bounteous friend of the Hospitallers and of Mance herself.

But in the spring of 1651 the Iroquois attacks became so frequent that Ville-Marie thought its end had come. M. de Maisonneuve made all the Montrealers take refuge in the fort. Mlle Mance, with her sick, her wounded, and her poor, came in also, reoccupying the rooms she had had when Ville-Marie was founded. Soon, exclaimed M. Dollier, no man ventured “to go four steps from his house without carrying his gun, his sword and his pistol. Finally, as we were getting fewer every day . . . , our enemies took heart from their greater number.” M. de Maisonneuve saw fall, one by one, his beloved settlers, whom he considered it his duty to protect. Gradually, he made up his mind to put an end to the attacks. But now Jeanne Mance suddenly intervened: she placed at Maisonneuve’s disposal 22,000 livres from the unknown benefactress, for raising a contingent of soldier-workmen.

In the autumn of 1651, the Montrealers saw M. de Maisonneuve leave for France. All things considered, the governor could not reject the offer made by the hospital’s wise director. As he handed over to d’Ailleboust Des Muceaux the leadership of Ville-Marie, he uttered these few words: “I shall try to bring back 200 men . . . to defend this site; if I do not have at least 100, I shall not return, and everything will have to be abandoned, for indeed the place would be untenable.”

M. de Maisonneuve’s stay in Europe lasted two years. While, at Montreal, Major Raphaël-Lambert Closse, his soldiers, and all able-bodied settlers were heroically resisting the Iroquois, in France M. de Maisonneuve was employing all possible means, assisted by M. de La Dauversière and the financial backing of the Associates of Montreal, to recruit numerous defenders for his post. But first of all, with a diplomatic subtlety that we are able to glimpse through M. Dollier’s account, M. de Maisonneuve decided to plead the cause of Montreal with the benefactress whose name Mlle Mance had disclosed to him. Without arousing the slightest suspicion in Mme Claude de Bullion – this was her name – that he knew of the relations between her and Jeanne Mance, he had dwelt at length upon Ville-Marie’s distress. The wealthy noblewoman was certainly impressed, for a short time later M. de Maisonneuve received from the hands of President Guillaume de Lamoignon, a cousin of the Bullions, and perhaps one of the Associates of Montreal, a sum of 20,000 livres, offered by a “person of quality” to M. de Maisonneuve to stimulate the recruitment of the settler-soldiers for Ville-Marie.

In the spring of 1653, the muster-roll could finally be drawn up. Out of the 149 men under contract, 102 honoured their signatures, and on 20 June 1653 they embarked on the Saint-Nicolas from Nantes. On 20 September, after a miserable crossing during which several of the new settlers were stricken by a contagious disease, the ship entered the roadstead of Quebec.

The welcome in the capital was enthusiastic. A Te Deum was sung in the church. Not until several weeks later did the contingent go to Ville-Marie, for a fair number of the settlers, having barely recovered from the fevers of the disease, had to spend a period in hospital. It was with great relief that the Montrealers received these soldiers, who had come from the various provinces of France, chiefly Maine and Anjou. They were going to save not only Montreal, but also the whole of New France, for the fall of Ville-Marie would inevitably have brought about the successive destruction of the other posts.

With the 1653 contingent there arrived at Ville-Marie a fine young woman, the future teacher of little Montrealers and young Indigenous girls: Marguerite Bourgeoys. The arrival of this woman with “a good mind,” and “whose virtue is a treasure,” was due to the sagacity of M. de Maisonneuve and of his sister, Mother Louise de Sainte-Marie, of the convent at Troyes. “This worthy girl whom I am bringing,” M. de Maisonneuve had declared to Mlle Mance, “. . . will be a tremendous help at Montreal; moreover, this girl is yet another product of our province of Champagne, which seems to want to give to this place more than all the others put together.”

Everything changed at Ville-Marie, and finally became settled. Thanks to the powerful reinforcements, the settlers gradually left the fort and went back to live in their little houses. Work in the fields kept many labourers busy. The governor of Montreal took advantage of the temporary peace, signed by the Iroquois in 1655, to return a fourth time to France. He persuaded M. Olier, in conjunction with his ecclesiastics, to provide the first parochial clergy of Montreal. The Jesuits found it difficult to carry on the ministry at Ville-Marie, for the number of their religious was barely adequate to staff their missions.

M. Olier acceded to M. de Maisonneuve’s request. He designated for parochial worship de Queylus [see Thubières], Souart, Galinier, and d’Allet. A few hours before their departure from Nantes on 17 May 1657, the Sulpicians learned of the death (2 April 1657) of their founder and superior M. Olier.

Jeanne Mance, who was getting old and whom an accident had deprived of the use of one arm, had brought back from France, in September 1659, the first Hospitallers of St. Joseph, Mothers Moreau de Brésoles, Macé, and Maillet. She thus fulfilled one of the vows most dear to M. de La Dauversière, who, it should be added, helped her to the best of his ability.

A year later, with the arrival of the ships from France, the Montrealers received the news of the death of Jérôme Le Royer de La Dauversière, the founder of the Société Notre-Dame de Montréal, who had passed away on 6 Nov. 1659. The disappearance of the procurator of the Associates of Montreal, who died ruined, even bankrupt, following a reverse of fortune not long before, brought about some changes. The Société Notre-Dame, the number of whose associates had gradually been diminishing, saw itself obliged to abandon the Montreal seigneury. On 9 March 1663 the surviving members, in the presence of Mlle Mance who was then in Paris and had brought M. de Maisonneuve’s consent, signed a deed of gift to the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice.

As the Iroquois had resumed hostilities at Ville-Marie, M. de Maisonneuve created, on 27 Jan. 1663, the militia of the Sainte-Famille to meet the danger. It was composed of 139 settlers divided into 20 squads. Each squad had as its leader a corporal elected by a majority.

That year, the Compagnie des Cent-Associés finally ceased to exist. On 24 February, at their last meeting, attended by only a few, the partners handed over New France to the Crown. The letters patent joining it to the royal domain were published the following month. Thenceforth Louis XIV was to guide the destinies of Canada. The following year the Communauté des Habitants (1645–64), completely ruined, disappeared in its turn.

The Marquis de Tracy [Prouville], newly appointed lieutenant-general of New France, landed at Quebec on 30 June 1665 with four companies of soldiers, who came like himself from the West Indies. Already, the preceding on 13 and 19 June, four other companies had arrived from France, a prelude to the dispatch of the famous Carignan-Salières regiment made up of 20 companies and comprising altogether some 1,000 fighting men. The king had decided to put an end to the Iroquois attacks.

The salvation of Canada was thus assured sooner or later, and the settlers, so sorely tried for years by the Iroquois war, could not do other than rejoice over the fact. But at Ville-Marie, in September 1665, a grievous piece of news depressed the spirits of the Montrealers and went straight to their hearts. M. de Maisonneuve, their good governor, this honest judge of all their differences, had just received from Tracy the order to return to France on indefinite leave. Was he surprised to receive such an order when he had to his credit 24 years of dedicated service? Certainly not as much as one might think. For some years he had not enjoyed the favour of the governors-general. M. de Saffray de Mézy, in particular, had displayed a truly regrettable intolerance and arrogance. To be persuaded of this one should read the accounts of Sister Morin, who can barely conceal her indignation. M. de Maisonneuve bore everything with dignity.

He left in the autumn of 1665, taking with him the regrets of his faithful little colony. He went to live in Paris, in seclusion, humble, ever discreet. The memory of the work accomplished at Ville-Marie kept his spirit serene and trusting until the end. He passed away 11 years later; at his bedside were his young friend Philippe de Turmenys and his devoted servant Louis Fin (not Frin). His funeral took place at the church of the Fathers of the Christian Doctrine, situated not far from the abbey of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont, and it was there that he was buried.

Had it not been for the constant activity of Jérôme de La Dauversière in France and of Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve and Jeanne Mance in Canada, the Société Notre-Dame de Montréal would have collapsed under the weight of countless trials and difficulties. Such tenacious leaders were necessary to keep alive for a quarter of a century the little post of Montreal, isolated from the rest of the colony.

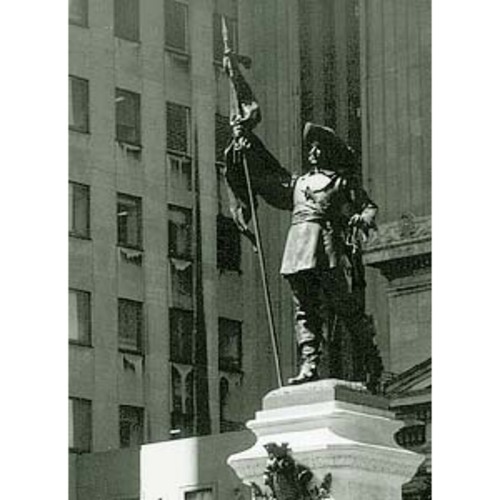

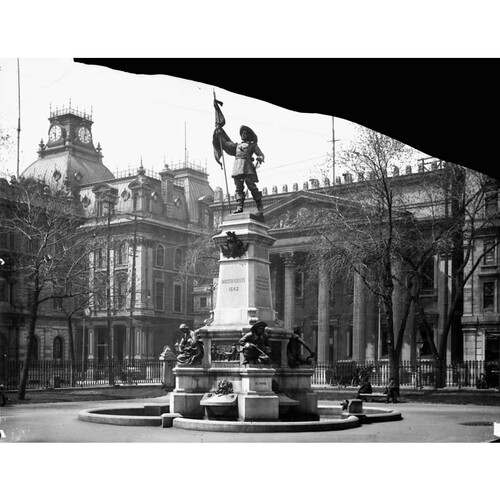

A monument was erected in 1895 on the Place d’Armes in Montreal, to the memory of M. de Maisonneuve. It is the work of the Canadian sculptor Louis-Philippe Hébert*. An imaginary model was used to represent Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve, for no authentic portrait of the first governor of Montreal exists.

[The definitive work on the character and achievements of the first governor of Montreal is still to be written. The biographies published to date are popular treatments, some of which present an overly romantic view. Critical appraisal is lacking. Although in this context an exhaustive bibliography is not appropriate, attention is drawn to the following works.]

Archives de l’Aube, Registre de catholicité de Neuville-sur-Vanne, acte de baptême, 1612. AHDM, Marie Morin, “Histoire simple et véritable de l’établissement des Religieuses Hospitalières de Saint-Joseph en l’Île de Montréal, dite à présent Ville-Marie, en Canada, de l’année 1659 . . .” AN, Col., C11A, 1, f.233, “Articles accordez entre les directeurs associez en la Compagnie de la Nouvelle-France et les habitants du dit pays, 6 mars 1645” (see Gustave Lanctot, Réalisations françaises de Cartier à Montcalm (Montréal, 1951), 57). ANDQ, Registres des baptêmes de Sillery. Dollier de Casson, Histoire du Montréal. JR (Thwaites).

“Inédits sur le fondateur de Villemarie: maintenue de noblesse, 1600,” éd. L-.A. Leymarie, NF, I (1925–26), 20–33. É.-Z. Massicotte, Répertoire des arrêts, édits, mandements, ordonnances conservés dans les Archives du Palais de Justice de Montréal, 1640–1760 (Montréal, 1919). Morin, Annales (Fauteux et al.). [Jean-Jacques Olier?], Les véritables motifs de messieurs et dames de la Société de Notre-Dame de Montréal pour la conversion des sauvages de la Nouvelle-France, éd. H.-A. Verreau (SHM Mémoires, IX (1880)). “Ordonnances de Mr. Paul de Chomedey, sieur de Maisonneuve, premier gouverneur de Montréal,” in Mémoires et documents relatifs à l’histoire du Canada (SHM Mémoires, III, 1860), 123–44.

E. R. Adair, “France and the beginnings of New France,” CHR, XXV (1944), 246–78. W. H. Atherton, Montréal, 1535–1914 (3v., Montréal, Vancouver, Chicago, 1914). Camille Bertrand, Monsieur de La Dauversière, fondateur de Montréal et des religieuses hospitalières de Saint-Joseph 1597–1659 (Montréal, 1947), 64. Daveluy, “Bibliographie,” RHAF, VII (1953), 457–61, 586–92, et passim; Jeanne Mance, 1606–1673, suivie d’un essai généalogique sur les Mance et les de Mance par M. Jacques Laurent (Montréal, 1934), 284–88. Faillon, Histoire de la colonie française. Robert Le Blant, “Documents inédits: les derniers jours de Maisonneuve et Philippe de Turmenyes, 14 avril 1666 – 9 septembre 1676 – 3 août 1699,” RHAF, XIII (1959–60), 262–80. L.-A. Leymarie, “Le fondateur de Montréal, Paul de Chomedey, sieur de Neufville; de Bourg-de Partie, de Saint-Chéron et de Maisonneuve (1672–1676),” NF, II (1926–27), 207–11; “Louise de Chomedey et les débuts de la congrégation de Notre-Dame à Ville-Marie,” NF, II (1926–27), 28–32. É.-Z. Massicotte, “Memento historique de Montréal, 1636–1760,” RSCT, 3d ser., XXVII (1933), sect.i, 111–31; “Notes et documents nouveaux sur le fondateur de Montréal,” BRH, XXII (1916), 139–50; “Pierre Gadois, premier concessionnaire de terre à Montréal,” ibid., XXIX (1923), 36f.; “Les premières concessions de terre à Montréal, sous M. de Maisonneuve, 1648–1665,” RSCT, 3d ser., VIII (1914), sect.i, 215–29. Mondoux, L’Hôtel-Dieu de Montréal. Émile Salone, La colonisation de la Nouvelle-France: étude sur les origines de la nation canadienne-française (Paris, 1906).

Bibliography for the revised version:

C.-V. Campeau, “Navires venus en Nouvelle-France, gens de mer et passagers, des origines à 1699”: naviresnouvellefrance.net (consulted 28 March 2023). Gustave Lanctot, Montréal sous Maisonneuve (Montréal, 1966). Michel Langlois, Montréal 1653: la grande recrue (Sillery [Québec], 2003). Robert Rumilly, Histoire de Montréal (5v., Montréal, 1970–74), 1. Marcel Trudel, Montréal: la formation d’une société, 1642–1663 (Montréal, 1976).

Cite This Article

Marie-Claire Daveluy, “CHOMEDEY DE MAISONNEUVE, PAUL DE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 8, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/chomedey_de_maisonneuve_paul_de_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/chomedey_de_maisonneuve_paul_de_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | Marie-Claire Daveluy |

| Title of Article: | CHOMEDEY DE MAISONNEUVE, PAUL DE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 2023 |

| Access Date: | April 8, 2025 |