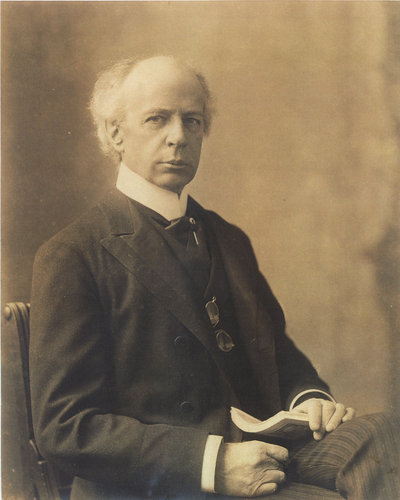

Sir Wilfrid Laurier

Source: Link

A legend in his time, Sir Wilfrid Laurier evolved as a politician over a period of 48 years, which included 15 years as prime minister and 32 years at the helm of the federal Liberal Party. He belonged to the first generation of politicians who worked in the Canada conceived by the Fathers of Confederation. This thematic ensemble gives an overview of his life and public career. Its seven sections explore illustrative moments in the history of Canada and tell of the words and deeds of the first French Canadian to become prime minister of this country.

After articling in the firm of Toussaint-Antoine-Rodolphe Laflamme, Laurier became a lawyer in 1864 and would practise law for some 30 years during his political career. He was invited by Laflamme to join the Canadian Institute, a Montreal literary circle and salon of Rouge sympathizers, where he became an active member and met influential intellectuals such as the brothers Joseph and Gonzalve Doutre. To this legal facet of his career we must add journalism. Together with associates and colleagues such as Pierre-Joseph Guitté and Médéric Lanctot, Laurier used newspaper articles to express his initial opposition to confederation and set out his views on liberalism and current political issues. “Laurier liberalism,” which evolved over time, ultimately rested on civil and religious liberties allied to the principles of tolerance, conciliation, and compromise, as he stated in a memorable speech in Quebec City on 26 June 1877. When he became a prominent politician as well as the owner of a newspaper at the end of the 19th century, Laurier, in keeping with journalistic practices of the times, intervened in matters of content, issuing directives to editors such as Ernest Pacaud.

Laurier worked his way up in politics, backed by a vast network of friends and advisers such as Laurent-Olivier David and Charles-Alphonse-Pantaléon Pelletier. Elected for the first time in 1871 to the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Quebec, he was re-elected in 1874, this time to the House of Commons, where he would spend the rest of his career. He was minister of inland revenue in 1877–78, but spent the better part of his first 25 years in parliament on the opposition benches.

Laurier was head of the Liberal Party of Canada from 1887 to 1919. His pragmatism in politics, combined with the organizational talents of men such as James David Edgar, Rodolphe Lemieux, and Ernest Lapointe, helped to transform the party into a truly national organization better positioned to win elections. To achieve this goal, and wishing to contribute to the rapprochement between French and English Canadians, Laurier relied on strengthening the unity of the nation and the unity of his party. These leading principles guided his political acts and shaped, in particular, his conception of Canadian federalism. As well, these principles were essential to Laurier’s efforts to develop an advantageous association with his own province and a means to better the relations of Roman Catholic religious authorities with Quebec and with the rest of Canada.

As prime minister from 1896 to 1911, Laurier was in command of his followers, and he confronted a series of challenges in masterful style. The biographies of Andrew George Blair, Joseph-Israël Tarte, and Simon-Napoléon Parent illustrate the importance Laurier attached to ministerial solidarity and his diligent practice of distributing favours. While typical of the politics of the time, patronage nevertheless became a source of scandal and controversy for the Laurier government. For example, the biography of Henry Robert Emmerson shows that he plunged the Liberal cabinet into embarrassment more than once. Laurier, however, was never personally implicated in these matters.

Among the priorities of the Laurier government were economic development and the extension of settlement westward, activities in which the ministers William Stevens Fielding and Clifford Sifton played leading roles. To achieve these ends, Laurier specifically implemented policies on openness to immigration, the modernization of agriculture, and the construction of new transportation infrastructure. He wanted, among other things, his name and memory to be associated with the building of a transcontinental railway, especially given that the Canadian Pacific Railway Company could no longer move all the country’s industrial products and agricultural goods. This new line, the National Transcontinental, which Laurier described in 1903 as an “absolute necessity,” was for him the best symbol of the success of liberalism, material values, and, ultimately, progress.

Railway entrepreneurs such as Charles Melville Hays of the Grand Trunk Railway, in whom Laurier had confidence, contributed to this second transcontinental line while Donald Mann and William Mackenzie, of the rival Canadian Northern Railway, were able to build their own line. At the time, Canada, particularly in the east, was noticeably characterized by urbanization and industrial expansion, and the prime minister wanted to emphasize his country’s entry into the 20th century.

All these changes did not occur without turmoil for Indigenous people. To favour the economic interests and ensure the safety of the settlers and prospectors who, in this period, rushed towards the natural resources of the North-West Territories, which did not yet belong to confederation, the Laurier administration concluded Treaty No.8 with Indigenous people in 1899 [see David Laird; James Andrew Joseph McKenna; Mostos; Sir Clifford Sifton]. For members of these western First Nations, who believed that the agreement would ensure peace and friendship with the whites, the main result was the transfer of large swathes of their territory, constituting what are now areas of northern British Columbia, Alberta, and Saskatchewan, and a part of the southern Northwest Territories. In exchange for the land, the federal government guaranteed annuity instalments, the protection of hunting, fishing, and trapping rights, and a reconsideration of the principle behind – and the method for allocating – reserves. Indigenous people would later see this treaty as unfair. Moreover, the repressive policy of the Department of Indian Affairs (including, for example, the placement of children in residential schools designed to assimilate them into Euro-Canadian culture and sanctions against traditional dances) continued under the reign of Laurier's Liberals [see Ahchuchwahauhhatohapit; Matokinajin; Mékaisto]. For asserting their rights to have their economic system and their lifestyles protected, Indigenous people found in Lord Minto, governor general of Canada, a defender of their cause in dealing with the government.

Laurier was also anxious to increase his country’s autonomy on the international stage. He wished to maintain the link with the British empire until Canada was strong enough to assume what the prime minister considered its destiny. With this course of action, he hoped to calm the imperialist sentiments of some English Canadians (imperial nationalists). Yet he took care not to alienate those French Canadians who were reluctant to take part in imperial wars (Canadian nationalists). A pertinent example of this approach is the episode of his handling of the Boer War (1899–1902). After indicating that his decision would not constitute a precedent for the future, Laurier authorized the raising and deployment to South Africa of military contingents composed mainly of English-speaking volunteers under British command. Furthermore, his government worked to settle border disputes with the United States and established a Department of External Affairs in 1909. Earlier, the prime minister had relied on the advice and negotiating skills of Louis-Philippe Brodeur, William Stevens Fielding, George Christie Gibbons, and Joseph Pope, who became the first deputy secretary of state in the new department.

Laurier was less successful in defending the right to separate schools for Roman Catholic minorities outside Quebec. For example, the regulation set forth in the Laurier–Greenway agreement of 1896, which confirmed that Manitoba’s separate schools would not be reinstated while allowing Roman Catholic religious instruction under strict conditions, illustrates Laurier’s method of achieving political compromise. Through a series of modest arrangements, the prime minister hoped to satisfy the Roman Catholic minority while bending to the will of the Protestant majority in Manitoba.

The Manitoba school question brings to mind certain arrangements that prevailed during the creation of the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan in 1905, and they led to another crisis for the rights of Roman Catholic minorities. Contrary to a federal law of 1875 that guaranteed subsidized separate schools for the Catholic minority in the North-West Territories, the territorial government had imposed ordinances in 1892 and 1901 that made it increasingly difficult for such schools to exist [see Charles-Borromée Rouleau; Sir Clifford Sifton]. In 1905 these restrictions were becoming a status quo imposed on the minority. Hoping that he would not be compelled to use them as a shield, Laurier tried, this time, to give precedence to article 93 of the British North America Act. According to his interpretation, it stipulated that separate schools located in a province or territory that wished to join confederation had to be protected. Once again confronted with a rebellion in his own cabinet, Laurier ultimately had to comply with the 1892 and 1901 laws, all the while maintaining his desire for obtaining a separate Roman Catholic school system that would be as similar as possible to the one guaranteed in the 1875 federal statute. He emerged from the episode politically weakened. Moreover, this latest case led Henri Bourassa, mentor to the Canadian nationalist movement, as well as many French Canadian Catholics, to accuse Laurier of having made too many concessions to the Anglo-Protestant majority to preserve national unity, thereby threatening the bicultural character of Canada as envisioned by the Fathers of Confederation. These events illustrate once again Laurier’s desire to choose the path of pragmatism as a tool to resolve these crises.

In 1912, when the government of Ontario imposed Regulation 17 on the French Canadian minority, limiting French to being the language of instruction in only the first two years of elementary school, Laurier adopted a different attitude. In 1916 he vigorously defended the rights of Franco-Ontarians by means of the motion made by mp Ernest Lapointe, which exhorted the Ontario government to reconsider Regulation 17. Two reasons may explain Laurier’s about-face. He had had enough of yielding, since the late 19th century, to the opinions voiced by Orangemen such as D'Alton McCarthy, who advocated a Canadian society unified by language and religion. Moreover, since Regulation 17 was imposed in Ontario, home to more than 200,000 of his francophone compatriots, Laurier thought that the spectre of anglicization was so geographically close to the province of Quebec that it would deal a fatal blow to the future of French Canadians.

Support for the proposed solutions to these complex problems was not unanimous; the already-deep divisions between francophones and anglophones in Canada were accentuated. The creation of a navy in 1910 further fanned discontent among Canadian nationalists and imperialist nationalists who were displeased that Laurier would not moderate his policy of compromise. According to the former, Laurier’s bill had blindly committed Canada to imperial military adventures, while the latter accused him of not doing enough. Canada’s trade relations with the United States further infuriated imperialist nationalists. Prime Minister Laurier was not able to implement a reciprocity treaty with the United States because industrialists and imperialists feared that it would destroy the Canadian economic structure. The imperialists also feared that reciprocity would weaken Canada’s ties with the empire. These two issues, the navy and reciprocity, were at the heart of the federal election of 1911.

Worn out by 15 years in power and having been unable, among other things, to respond adequately to the expectations of certain interest groups or adjust their laissez-faire 19th-century liberalism to the realities of a society undergoing profound change, the Liberals suffered defeat. In particular, Laurier had presumed that Canadians would be satisfied with the timid social reforms he had put in place to address urban and industrial problems, such as the chronic poverty of the lower classes and difficult working conditions in the manufacturing sector. Opponents of the prime minister had promised to attack him on all these issues, and they kept their word. The Conservatives, led by Robert Laird Borden, won the election.

Wanting above all to regain power, Laurier remained at the head of his party and regrouped. He attempted to organize the opposition, notably with the help of fiery mps such as William Pugsley in the House of Commons and, especially, in the Liberal-majority Senate with Sir George William Ross as head of the parliamentary wing. Laurier, who had turned 70 in November 1911, surprised many with his vigour. He staunchly resisted military conscription during the First World War; the issue led to one of the worst political crises in Canadian history and to division within his party. The Unionist victory in the federal election of 1917, the last contest in which Laurier took part, revealed a clear, dramatic division between francophones and anglophones, with the francophone electorate of the province of Quebec standing solidly behind him. Such national fragmentation, along with the split of the Liberal Party, dealt a major blow to the fundamental goals of the Liberal leader’s career. At his death in February 1919, the unity of the country and of his party appeared to be on very shaky ground.

Laurier’s place in history remains that of a nation builder. His tremendous popularity led to his victories in four consecutive elections. Historian and biographer Réal Bélanger presents the following portrait of the man:

“Despite disappointments and often justified criticisms, Laurier was already a legend; he had gradually achieved the stature of a giant, a symbol personified. And what an engaging personality! Few people at the turn of the century could resist his charm and courtesy. When necessary, Laurier was able to abandon his prime ministerial ways for a simplicity that won over the most obdurate hearts. His disarming frankness despite his subterfuges, his exceptional honesty in a rather lax environment, his respect for others regardless of differences of opinion, his unshakeable loyalty to the Liberal cause and to his friends, his determination and firmness despite moments of discouragement and the limits already mentioned, all aroused the admiration of many Canadians. Even his opponents were captivated.… Laurier indeed was not of a piece. He did not see things in black and white, and no doubt he had developed a personality that enabled him to face the complexity and harshness of his milieu at any time. He was nevertheless a man of honour, generous, enamoured of liberty, and able to confer nobility on the causes he supported. A humanist, he found arrogance, bigotry, and intolerance repugnant.”

The biographies included in this thematic ensemble shed light on Laurier and on a turning point in Canada’s development. We invite you to learn about the life of the individual whom Lord Minto once described as by “far the biggest man in Canada.” According to his biographer, “this was the portrait of Sir Wilfrid Laurier that in the end has remained in the collective memory.”