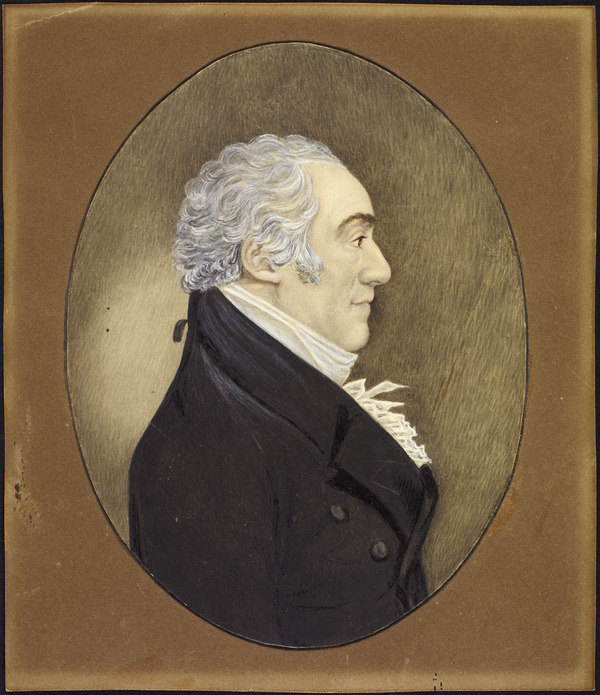

RICHARDSON, JOHN, businessman, politician, jp, office holder, and militia officer; b. c. 1754 in Portsoy, Scotland, son of John Richardson and a daughter of George Phyn; m. 12 Dec. 1794 Sarah Ann Grant, a niece of William Grant*, and they had seven children; d. 18 May 1831 in Montreal.

John Richardson studied arts at King’s College, Aberdeen, Scotland, before becoming apprenticed in 1774, through family connections, to the successful Scottish fur-trading partnership of Phyn, Ellice and Company, then with headquarters at Schenectady, N.Y. After his arrival in May, deteriorating relations between the American colonies and Britain forced the firm to reorganize. Richardson’s uncle James Phyn established a supply house in London, and two years later Phyn’s partner Alexander Ellice* shifted the main base of North American operations to Montreal. Early in the American revolution Richardson was taken into the employ of John Porteous, a former partner in Phyn, Ellice and a main supplier of the British troops in New York and Philadelphia. In 1779 Richardson was employed as captain of marines on the privateer Vengeance, principally owned by Porteous, but in which Richardson had shares. The letters he wrote during the ship’s first cruise evince one of Richardson’s dominant traits, an aggressive confidence in himself and those he considered his mates. “Let us only see a Vessel and we are not afraid but we will soon come up with her,” he boasted. The letters also describe exhilarating adventure, the duplicity of prize crews, and above all the dangers and confusion of privateering. On 21 May 1779 the British naval vessel Renown, paying no attention to the British flag on Vengeance, fired five or six broadsides into her, wounding several of the crew, some mortally, and severely damaging the hull. Even after identity was positively established, the captain of Renown expressed no regret and left a dismasted Vengeance to its fate, a “wanton and unprovoked cruelty,” Richardson wrote, “unworthy of a Briton.”

By August 1780 Richardson had established a shop in Charleston, S.C., in association with Porteous and Phyn, Ellice and Company of London, to whom he exported indigo, rice, and tobacco. His letters from Charleston reveal a diligent mind, already attuned to accounting and very shrewd on matters of supply and demand in consumer goods ranging from fashionable cocked hats and artificial flowers to saddles. The letters also express hatred of disloyalty, an attitude Richardson would reveal time and again in Lower Canada.

After the peace in 1783, Richardson was again employed by Phyn, Ellice interests in New York and Schenectady. In 1787 he was sent to Montreal to help his cousin John Forsyth* reorganize Robert Ellice and Company, the successor to Alexander Ellice and Company. The firm had greatly overextended its operations south of Detroit and Michilimackinac (Mackinac Island, Mich.) and its principal partner, Robert Ellice*, was ailing. In the years 1787–89 Richardson divided his time between Montreal and the west. In the city he learned the details of the firm’s business: the Montreal-southwest fur trade, speculation in bills of exchange, the collection from the government and payment to the recipients of loyalist compensations, and the forwarding of supplies to loyalist and military settlements in Upper Canada. In the west he supervised and reported on the trade – which was sadly depressed – and oversaw construction of the company’s schooner, Nancy, designed for use on lakes Huron and Michigan. When Robert Ellice died in 1790 Richardson was made a partner in the reorganized firm, called Forsyth, Richardson and Company. Although the cousins were determined to avoid the costly excesses of Robert Ellice, they were far from stodgy. In the next few years their firm expanded the forwarding trade, particularly to Kingston and York (Toronto), increased investment in shipping on the Great Lakes, became a minor shareholder in the North West Company, and was involved in the unsuccessful Montreal Distillery Company [see Thomas McCord], which ceased operation in 1794. One of Richardson’s most imaginative initiatives was an attempt, through Forsyth, Richardson and in conjunction with Todd, McGill and Company of Montreal [see Isaac Todd*] and Phyn, Ellices, and Inglis of London, to found a bank in 1792. The Canada Banking Company was designed as a bank of note issue and of discount and deposit; it might have fulfilled a need stemming from the scarcity, variety, and unreliability of specie in circulation, but it proved premature. In this period, as later, Forsyth, Richardson was also active in lobbying local and imperial governments for political changes in the interest of commerce. For example, in 1791–92 it joined with other fur-trading concerns in opposing the evacuation of western military posts on American territory held by the British since the end of the revolution, a campaign which may have influenced retention of the posts until 1796.

From the outset of his residence in Montreal, Richardson identified with the merchants’ movement for an elected assembly and the introduction of English commercial laws [see George Allsopp*; William Grant]. In 1787 he lamented that government obstructed the way of mercantile men at every turn when it “ought to acknowledge commerce as its basis, & the accommodation of the Merchant as one principal means of promoting the national prosperity.” In March 1791 he joined colleagues from the colony and interested London merchants to petition against the bill that became the Constitutional Act. Examined at the bar of the House of Commons, he opposed the division of the colony on which the bill was based and the retention of French civil law, which favoured debtors over creditors, in the province of Lower Canada.

Although disappointed by the new constitution, Richardson stood in 1792 in the first general election held under it. He and Joseph Frobisher* were elected for Montreal East with “a great majority,” having been supported by leading British merchants and Canadians such as Thomas McCord and Joseph Papineau*. He immediately assumed a role of leadership among the merchants in the House of Assembly. In February 1793, during an acrimonious debate over the language of legislation, he moved that the English alone should be the legal text of statutes. Ever forthright, he read his elaborate paper of justification only in English and bluntly stated that the “dearest interests” of the Canadians would be fostered if they would but accept a “gradual assimilation of sentiment” to the ways of His Majesty’s old subjects. His intervention kept the political pot boiling for some weeks. Ultimately he succeeded; the governor was later instructed to assent only to the English version of bills, including those on civil law, for which the assembly had decreed that French would prevail. Richardson proved to be a member of prodigious energy in such matters as proposing and amending bills, drafting addresses to the governor, negotiating with the Legislative Council, improving the rules governing debate, and – ironically in view of subsequent events – asserting the assembly’s exclusive privilege to initiate money bills. He was also highly effective; bills presented by him which became law dealt with the negotiability of promissory notes, the importation of potash from the United States, the rating of gold coins, the prevention of fraud by engagés, the regulation of registers of civil status, and the publication of statutes.

Richardson’s experience in the assembly left him frustrated, nevertheless. The Canadians, he wrote to Alexander Ellice during the first session, caucused out of doors on all questions, and trying to change their minds was “like talking to the Waves of the Sea.” There was a faction among them, he felt certain, which was “infected with the detestable principles now prevalent in France.” Nothing could possibly be “so irksome as the situation of the English members . . . doomed to the necessity of combating the absurdities of the majority, without a hope of success.” He did not stand for election in either 1796 or 1800.

From the outbreak of war with revolutionary France, Richardson exerted himself to the utmost in the interest of security. It was he who proposed the assembly’s unanimous address to Lieutenant Governor Alured Clarke of April 1793, which promised total cooperation and characterized the execution of Louis XVI as “the most atrocious Act which ever disgraced society.” In 1794 he contributed important amendments to the Militia and Alien acts, the latter of which temporarily suspended habeas corpus, and was active on the Montreal committee of the Association, founded that year to support British rule. In October 1796, at the height of riots in Montreal over a new road act, Richardson was among a number of justices of the peace chosen to replace magistrates deemed by Governor Robert Prescott* to have been too timorous in dealing with the rioters.

During late 1796 and in 1797 Richardson acted as the chief of Lower Canadian counter-intelligence, intercepting correspondence, having suspected traitors examined, and directing a string of informers from Montreal to the American border. He learned that the French minister to the United States was sending “emissaries” into Lower Canada to assess the attitudes of the habitants towards France, examine the colony’s defences, and establish a fifth column to support a naval invasion projected for the summer or fall of 1797. The evidence Richardson compiled was used to arrest three Montrealers on charges of treason in February 1797 (they were later acquitted), to justify the Better Preservation Act, again suspending habeas corpus, which Attorney General Jonathan Sewell* successfully piloted through the legislature, and to build the crown’s case against David McLane*, executed for treason in July 1797. Although sceptical of his informers’ more grotesque tales, Richardson, like most of the governing élite, greatly exaggerated the danger: the Road Act riots, he thought, had been an attempt at insurrection fomented by emissaries; the French would send a fleet with up to 30,000 troops and find active support among the habitants and among disloyal politicians such as Joseph Papineau and Jean-Antoine Panet*, the leaders of a party of “Sans Culottes” in the assembly. In February 1797 Richardson urged a declaration of martial law as the only action that would adequately protect people of property from “all the horrors of assassination.” When in July 1801 government officials learned that the Vermont adventurer Ira Allen had established a secret society in Montreal, Richardson was put in charge of the investigation; it resulted in the arrest of some of the ringleaders and proof that the society’s aim had been to proliferate branches in the Canadas in order to provide support for an invasion from Vermont. Richardson was also an ensign in the British Militia of the Town and Banlieu of Montreal from 1794, and took the lead in establishing in 1801 a volunteer armed association, which carefully watched strangers, drilled, and in October patrolled the streets of Montreal at night.

About the turn of the century Richardson’s business interests were reaching a critical point. With the exhaustion of prime beaver south of the Great Lakes and problems stemming from American tariff duties and settlement already evident, Forsyth, Richardson and Company had begun trading extensively in the northwest in opposition to, among others, the NWC, which it had left by 1798. That year, in order to sustain the intense competition that developed particularly with the NWC, Forsyth, Richardson, together with Phyn, Ellices, and Inglis, the Detroit firm of Leith, Jameson and Company, and six wintering partners, founded the copartnership of the New North West Company, also called after 1799 the XY Company or the New Company. In 1800 the copartnership received an injection of capital and expertise when the famous explorer Alexander Mackenzie* and two partners in the successful Montreal firm of Parker, Gerrard, and Ogilvy – John Ogilvy* and John Mure – joined its ranks; from 1802 it was occasionally known as Sir Alexander Mackenzie and Company. Competition with the NWC became economic warfare, dividing British Montreal into two camps. From 1799 to 1804 the New North West Company tripled its investment in the annual outfit from about £8,000 to almost £25,000. By the latter year, it had secured about one-third of the northwest trade, and its share was growing.

The competition, however, was ruinous: massive quantities of trade rum demoralized the Indians, and costs spiralled, while the exchange value of trade goods plunged. As Edward Ellice*, Alexander’s son, later commented, the only question was which company was losing most heavily. Crimes such as bribery of employees and theft of trade goods were commonplace. Indians were induced to pillage or fire on rival canoes. In one instance a clerk of the New North West Company shot to death an opposition clerk, but when he was brought to trial in Montreal in 1802 it was discovered that no court in British North America had jurisdiction over felonies committed in the Indian country. Reporting on the situation at the request of Lieutenant Governor Sir Robert Shore Milnes* of Lower Canada, Richardson concluded that if jurisdiction was not conferred on Canadian courts, force might well come to prevail over justice in the northwest, in which case “the Fur Trade must in the end be annihilated.” Milnes urged Richardson’s recommendation on the colonial secretary, Lord Hobart, as did Mackenzie. The result was an imperial act in 1803 giving jurisdiction for crimes in the Indian country to the courts of Lower Canada (and in some circumstances to those of Upper Canada) and giving the head of the administration of the lower province power to appoint magistrates in the interior. With competition driving both companies towards bankruptcy and the wintering partners fearing for their lives, amalgamation was arranged in 1804, the New North West Company acquiring one-quarter of the shares in a reorganized NWC.

Meanwhile, thanks no doubt to the diversity of its interests and the solidity of its London backers, Forsyth, Richardson was doing well. In 1803 a merchant from Albany, N.Y., estimated the value of its exports at £40,000, placing it third in Montreal after the NWC (£150,000) and Parker, Gerrard, Ogilvy and Company (£85,000). The importance of Upper Canada and the northwest to its operations is evident: that year it seems to have sent up the St Lawrence as many bateaux as the NWC.

At Milnes’s insistence, a reluctant Richardson again stood for election in 1804. He won a seat for Montreal West and once more took the lead among the English representatives. In 1805 he became embroiled in a controversy over whether the building of jails should be financed by land taxation – as Richardson had pledged during the election – or by duties imposed on imports, the burden of which would fall mainly on the northwest fur trade. The following year he was prominent in futile attempts by the mercantile contingent in the assembly to have the Gaols Act disallowed and to prevent the majority from ordering the arrest for libel or contempt of Isaac Todd and newspaper editors Thomas Cary and Edward Edwards*, who had all denounced the act in ironic terms. In 1807 and 1808 he fought unsuccessfully for measures designed to promote immigration into the Eastern Townships and improve agricultural production and against passage by the assembly of a bill to render judges ineligible for election. Despite an ever-worsening political polarization, Richardson had some successes: his bills for regulating river pilots, improving the Montreal–Lachine road, and funding the improvement of navigation on the St Lawrence, among others, reached the statute books.

In April 1808 Richardson spoke at length in support of a bill he had introduced for incorporation of a “Bank of Lower-Canada.” Although flawed to modern eyes by its adherence to the commodity theory of money value, the speech was nevertheless a stunning performance. With marvellous lucidity he traced the evolution of paper money, expounded the general principles of banking, and laid to rest numerous objections. He explained how short-term discounting worked, why the issuance of bank notes had to exceed specie holdings, why bank failures would be uncommon, and how counterfeiting could be severely curtailed. A brilliant stroke was his explanation of a seeming paradox: that corporate banks of limited liability but regulated as to investments and the issuing of notes were safer than private banks of unlimited liability. Richardson’s speech and the bill were printed for public edification. Although the bill fell victim to prorogation of the legislature, both contributed greatly to gradual public acceptance of paper money and banking during the next decade.

Richardson’s controversial stands in the assembly alienated the Canadian voters in Montreal West, and he was defeated in the election of 1808. He was not silenced politically, however, for he had been appointed an honorary executive councillor in December 1804 and had taken his seat on 25 Nov. 1805. As he had arranged with Milnes, he attended council meetings only when in Quebec for the legislative session or on business, but he was available for committee work in Montreal. During the session of 1808 he was designated by Governor Sir James Henry Craig* official messenger from the Executive Council to the assembly on matters affecting the royal prerogative, a prestigious nomination previously accorded to John Young* and James McGill*. In December 1811 Richardson became a regular member of the council, and he held his seat until his death. As an executive councillor he was a particularly influential adviser of hard-line governors such as Craig and Lord Dalhousie [Ramsay*], but he was consulted much less by the conciliatory Sir George Prevost* and Sir James Kempt*. Among Richardson’s duties was that of judge when the Executive Council sat as the Court of Appeals. Although a layman, he had a sound grasp of legal principles and could absorb legal detail quickly. In 1821 he delivered a council judgement that only clergymen of the “established” churches – Roman Catholic, Anglican, and Presbyterian – were empowered to keep official registers of baptisms, marriages, and burials, a restrictive decision later rectified by a number of provincial statutes.

During the war against Napoleonic France, Richardson again immersed himself in myriad aspects of the colony’s security. In 1803 informers were set to work in Lower Canada and American border towns to ferret out the doings of emissaries. Rumours emanating from Paris that the colony would be attacked were reported by Richardson. A visit by Jérôme Bonaparte to the United States was carefully charted, and a suspicious fire in Montreal investigated. In 1804 Richardson drafted a bill to reward those who apprehended army deserters; it was presented by McGill and enacted. At Milnes’s urging Richardson used secret-service money to turn Jacques Rousse – an expatriate Canadian who in 1793–94 had spied for the French minister to the United States – into an effective double agent.

By 1804 Richardson had come to believe that American foreign policy, dictated by France, was building towards war with Great Britain, and that secret clauses in the Louisiana Purchase treaty had promised the United States French military assistance should it attack the Canadas. These assessments, conveyed periodically to Civil Secretary Herman Witsius Ryland* and no doubt to other government officials, probably helped to shape the extremely pessimistic view of security taken at the Château Saint-Louis. After 1807 Richardson seems to have been less active in intelligence, although in 1809 he acted as the channel of secret communication from John Henry*, a spy used by Craig to explore the possibilities of New England separatism in case of war. In 1810, during Craig’s so-called Reign of Terror (thoroughly approved of by Richardson), he was an active member of a committee formed from the Montreal members of the Executive Council which arrested three supporters of the Canadian party on suspicion of treason, examined numerous witnesses, and concluded (on thin evidence) that a Napoleonic plot aimed at “preparing the general mind” for insurrection had been narrowly thwarted.

In the decade after his final retirement from electoral politics, Richardson devoted much attention to problems of Lower Canadian merchants. In May 1810 he was chairman of an apparently short-lived Montreal committee of trade, probably formed, like one at Quebec the previous year [see John Jones*], to pressure the British government for improved conditions of trade, including better protection from American competition. Richardson was the Montreal head of a colonial lobby from 1809 to 1812 which persuaded the British parliament to prohibit inland importation from the United States of foreign products such as cottons and teas, although it failed to have American produce barred from the West Indies. More threatening to his personal interests were the growing assertion by the United States of jurisdiction over the southwest fur trade and the American government’s discrimination against British traders in favour of John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company. Faced with high tariffs, seizures, embargoes, and other attempted exclusions, Montreal traders to the southwest – of whom Richardson and William McGillivray were the principals – had joined together in the Michilimackinac Company in 1806 [see John Ogilvy]. In 1810–11 Richardson and McGillivray reluctantly but realistically negotiated an amalgamation with Astor. The resulting agreement of January 1811 formed the South West Fur Company and gave Astor a 50 per cent interest with Forsyth, Richardson, and McTavish, McGillivrays and Company sharing the other half as the Montreal Michilimackinac Company; later the NWC purchased one-third of the interest of the Montreal firm. It was the British firms in the South West Fur Company which, through Richardson, gave Governor Prevost, commander-in-chief of the British forces, his first news of the American declaration of war in June 1812, a war the British and Canadian traders had looked forward to in hopes that the British abandonment of the southwest by treaty in 1783 and 1794 and militarily in 1796 could be permanently reversed.

Richardson and McGillivray exercised considerable influence on events in the west during the war. The enthusiastic support given by the agents, engagés, and dependent Indians of their companies enabled a small British force under Charles Roberts* to seize Fort Michilimackinac on 17 July 1812. The two men personally persuaded Prevost of the political and economic value of the southwest trade and of the fort’s strategic importance for securing it. On their eulogistic recommendation and that of James McGill, Prevost commissioned the trader-adventurer Robert Dickson to raise an Indian force; it played a part in the successful defence of the fort under Robert McDouall* in August 1814. The chagrin of the two traders knew no bounds when it was learned that the peace negotiators had restored Michilimackinac to the Americans, and their legalistic interpretation of the Treaty of Ghent –a special pleading for delay – did not avail. Worse followed. In 1816 Congress closed the Indian trade to non-Americans. The next year, in a buyer’s market, Richardson and his colleagues sold their South West Fur Company shares to Astor and withdrew from the southwest trade.

On the domestic front during the war Richardson served in the Montreal Incorporated Volunteers and attended to routine duties as executive councillor. He watched with dismay as Prevost cultivated the support of the Canadian party at the expense of those who had had Craig’s ear. In 1814 Prevost reluctantly accepted the assembly’s impeachment of chief justices James Monk and Jonathan Sewell for, among other things, having promulgated “unconstitutional” rules of practice. Although certain that Prevost’s policy of conciliating the Canadian party was encouraging “the turbulent and revolutionary demagogues, who at present sway the Assembly,” Richardson successfully countered Sewell’s suggestion that the governor be attacked publicly. An open collision between Prevost and his Executive Council, which, as the colony’s Court of Appeals, supported the chief justices, “would curtail our means of defense . . . even in Military operations,” he asserted. He preferred “postponing such an extremity, to a more convenient season.” Richardson also asserted that the assembly’s impeachment of the chief justices alone should not be accepted, since they had had assistance in drafting the rules. “Every individual of every Court, is implicated,” he argued. “Let us stand or fall together!” Finally, Sewell should abandon his idea of using legalistic grounds to avoid a hearing before the Privy Council in London; rather the best hope for the security of the colony lay in exploiting “the intemperance of those anarchists” in the Canadian party. The exposing by Sewell of their “cloven foot” would likely force ministers to repress them – if Richardson had his way, by “taking away the Representative part of the constitution.” Richardson’s counsel on these and other matters was followed; Sewell and Monk were acquitted, though no constitutional repression was undertaken by the British parliament.

Tradition has assigned to Richardson authorship of a famous series of letters signed Veritas, which appeared in the Montreal Herald in April–June 1815 and later in pamphlet form. They unmercifully attacked the character and generalship of Prevost, described in one as an officer who had the “extraordinary fatality of either never attempting an active operation, or thinking of it only when the time for practical execution was past.” Although a plausible case can be made for the attribution to Richardson – especially since the letters were published only after the war – there is little direct proof, save the recollection 58 years later of a man who in 1815 had been a clerk in Forsyth, Richardson. Indeed, Prevost suspected Solicitor General Stephen Sewell to have been the author.

Following the war Richardson’s business interests underwent readjustment. His declining involvement in the fur trade dwindled further with the amalgamation of the Hudson’s Bay Company and the NWC in 1821. He had until then played a prominent role in defending the interests of the NWC in its struggle with Lord Selkirk [Douglas*] over the establishment and maintenance of Selkirk’s Red River settlement. Forsyth, Richardson and Company intensified its export of the newer staples such as grain and timber, while its interest in developing to the maximum its Upper Canadian trade is evident from Richardson’s fundamental role in the construction of the Lachine Canal. Long an advocate of such a water-way, on 26 July 1819 he was elected chairman of a committee charged by the newly formed Company of Proprietors of the Lachine Canal [see François Desrivières] with overseeing its construction. The company quickly ran into trouble, and in 1821 the colonial legislature took over its assets and appointed a commission to complete the project. On 17 July as chairman of the commission Richardson turned the first sod, and construction began. When the legislature momentarily ceased financing the project, advances were obtained from the Bank of Montreal on the personal security of Richardson and George Garden. Work was virtually completed in 1825.

Richardson and his company remained leading lobbyists. In August 1821 Richardson was named by a meeting of Montreal merchants to a committee to press for the removal of all restrictions on Lower Canadian wheat and flour in British and West Indian markets as a means of relieving the “state of depression and distress” that threatened them with ruin. The following year in Montreal he presided over the founding meeting of the Committee of Trade, successor to the committee of 1810; Thomas Blackwood* was elected chairman. In 1823–24 Forsyth, Richardson headed the list of mercantile houses which successfully sought reduction of the excise on tobacco imported into Great Britain from Upper Canada. Through John Inglis, a partner in the Ellice firm in London and a director of the East India Company, Forsyth, Richardson became in 1824 sole agents in the Canadas for the sale of East India Company teas, a lucrative contract it retained until after Richardson’s death. In this period Richardson was also much occupied, as Edward Ellice’s Montreal agent, with overseeing the management of the huge and rapidly developing seigneury of Villechauve, commonly known as Beauharnois. His strenuous efforts to enable Ellice to convert the seigneury to freehold tenure under the Canada Trade Act failed in the Executive Council in 1823 for legal reasons, but Ellice was later able to effect his aim under the Canada Tenures Act of 1825. Among Richardson’s many business involvements in the post-war period was his appointment as a director of the Montreal Fire Insurance Company in the early 1820s.

Richardson’s most absorbing concern, however, was finance. In 1817, spurred by the success of the army bills during the war [see James Green], nine merchants, among them Richardson, signed articles of association and invited stock subscriptions to form the Bank of Montreal, the first permanent bank in British North America and the progenitor of Canada’s chartered banking system. The guiding spirit was Richardson’s. His speech of 1808 was widely quoted by the bank’s supporters, he was chairman of the founding committee, and the articles, based largely on the charter of the First Bank of the United States, reflected his ideas. Although never a director, Richardson took a close interest as a shareholder in the bank’s affairs for the remainder of his life. On his instance the outer front wall of the bank’s first building, constructed in 1819 on Rue Saint-Jacques, displayed four much admired terra-cotta plaques from Coade of London depicting agriculture, arts and crafts, commerce, and navigation. That year, at the Colonial Office, he personally negotiated for royal assent to incorporation, which was finally granted in 1822. Richardson was unanimously elected to chair a critical stockholders’ meeting of 5 June 1826 at which a developing confrontation between a young guard among the directors under George Moffatt* and the older fur traders – Richardson, Forsyth, and Samuel Gerrard*, president of the bank – came to a head. Gerrard was deposed as president, but Richardson, with the largest single voting block of shares and proxies, was able to save him from further humiliation and enable him to remain as a director, thus preserving the bank’s unity. Richardson was a director of the Montreal Savings Bank, and in 1826 Forsyth, Richardson was appointed financial agent to manage the surplus funds of the receiver general of Upper Canada, a task it performed with profit and integrity into the 1840s.

Having declined earlier offers of a seat on the Legislative Council, Richardson accepted appointment to the upper house in 1816. There he supported all the mercantile and conservative causes with consistency and pugnacity. In 1821 he had the council pass a series of provocative resolutions which, going well beyond the pretensions of the House of Lords in matters of public finance, attempted to dictate to the assembly the form of its appropriation bills. The next year Richardson speculated in a council speech that a secret caucus of the Canadian party, redolent of the Committee of Public Safety in revolutionary France, might be planning to depose Governor Lord Dalhousie. The assembly called on the council to censure him and on the governor to dismiss him; both demands were rejected as threats to freedom of debate in the council. Throughout the 1820s he led those councillors – usually the majority – who were adamantly opposed to the assembly’s claim to appropriate crown revenues. In 1825, however, he stood almost alone in protesting passage by the council of a money bill negotiated with the assembly by Lieutenant Governor Sir Francis Nathaniel Burton, and in 1829 he led a minority attack on a similar bill worked out by Governor Sir James Kempt.

Richardson took a particularly active interest in a proposal in 1822 to unite the Canadas. As unrivalled dean of the colony’s business community, he chaired a public pro-union meeting in Montreal and gave a lengthy speech. Besides solving a long-standing and contentious problem of dividing import duties between Upper and Lower Canada, he said, union would enable Lower Canadian merchants to escape thraldom to the Canadian majority in the assembly, who were “anti-commercial in habits.” Not one to mince words, he told the crowd that the fundamental issue was whether they and their posterity would “become foreigners in a British land” or “the inhabitants of foreign origin . . . become british,” which could only be to the great benefit of the Canadians. Led by Richardson, six members of the Legislative Council protested its decision on 23 Jan. 1823 to oppose union. That night he wrote to Edward Ellice with ammunition for use against Louis-Joseph Papineau* and John Neilson*, who were being sent to London by the Canadian party to oppose union. He pointed out, for example, that Papineau’s weakness lay in his overweening self-esteem, that Neilson was so much a “Republican” as to have been obliged once to seek refuge in the United States, and that even Pierre-Stanislas Bédard, jailed in 1810 by Craig for attempted insurrection, had been contemplated as a delegate. These and further efforts by Richardson and Ellice were of no avail; the project was thwarted in the face of massive Canadian opposition.

Richardson was extremely active in public life. He was a charter member of the Montreal branch of the Agriculture Society in 1790. From 1793 to 1828 he was regularly appointed a Lower Canadian commissioner to negotiate a division of import duties with Upper Canada. In 1799 he was nominated treasurer to build a new court-house in Montreal and took a leading role in raising money for the imperial war effort. In the years 1802–7 he was successively named to commissions to demolish the city’s crumbling fortifications and design new street plans, to build a prison and a market house, to improve the Montreal–Lachine road, and to erect a monument to Lord Nelson. He headed a commission in 1815 to attract subscriptions for the families of soldiers killed or wounded at Waterloo, and in 1827 he was a leading promoter of subscriptions for a monument at Quebec to James Wolfe* and Louis-Joseph de Montcalm*. Richardson was appointed a trustee of the Royal Institution for the Advancement of Learning [see Joseph Langley Mills] in 1818 and was a moving force behind the foundation and early financing of the Montreal General Hospital, established in 1819 [see William Caldwell (1782–1833)]; he was the first president of the hospital after its incorporation in 1823. Among the many complicated estates that he helped settle was that of James McGill, a gruelling and thankless task except that it resulted in the beginnings of a university for his beloved city [see François Desrivières].

During the legislative session of 1831 a weary Richardson was at his post, protesting against whig conciliation, combating Papineau’s manœuvres to achieve control of the legislature for the Patriote party, as the Canadian party had become known, and fretting about backsliders on the Legislative Council, of which he became speaker on 4 February. He opposed, though unsuccessfully, the incorporation of Montreal, until then governed by appointed justices of the peace, for fear that through elections its administration would fall into the hands of the Patriote party. To Ellice he wrote of the Canadians as “spoilt children,” liberated by the British conquest, but trying to turn the tables on their “too generous emancipators.” He urged that there was “too much British Capital . . . at stake, to be handed over to Canadian Legislative management” and was outraged that the country which gave the “Law to Europe” might “be dictated to, by the descendants of Frenchmen.” Parliament should intervene to smash Papineau and his fellows. At the end of the session Richardson presented resolutions against the assembly’s attempts to obtain repeal of the Canada Tenures Act. According to a sympathetic executive councillor, Andrew William Cochran*, “his feelings were deeply wounded by the desertion or coldhearted support” of former allies: “‘Amidst the faithless, faithful only he.’” On returning home he took to his bed, Cochran wrote, lamented the treachery of his erstwhile political friends, and seemed “to give up hope and care for life.”

John Richardson died on 18 May 1831. Flags on the ships in harbour were flown at half-mast until the state funeral at Christ Church, where a plaque was dedicated to his memory. The English-language newspapers were full of deserved eulogies to him as a man of integrity in matters financial and political and one of the city’s greatest builders. A new wing of the Montreal General Hospital was constructed the following year as a permanent memorial to him. But even in death Richardson roused intense passions. Papineau pointedly had not attended the funeral, while Le Canadien and La Minerve reminded readers that Richardson had been the leader in Lower Canada of that party, called tory in England and ultra-royalist in France, which denied the people their just rights and by its excesses had recently turned Europe into a vast theatre of war and revolution.

Richardson’s interests went well beyond commerce and local politics. His aesthetic sense, like that of the British upper class in Montreal as a whole, was evident. The military surgeon John Jeremiah Bigsby* remarked that “at an evening party at Mr Richardson’s the appointments and service were admirable, the dress, manners, and conversation of the guests in excellent taste.” His wide-ranging curiosity led him to the presidency of the Natural History Society of Montreal, founded in 1827. He was well read in ancient and modern history, law, economics, and British poetry. The many comments on British, American, and European politics found in his letters are usually acute, if somewhat alarmist. Adam Smith was his preferred economist, but he was no unqualified believer in laissez-faire, as the provision in his bank proposal of 1808 for government participation and his continual lobbying for state assistance indicate. Byron was his favourite poet, but he did not admire the man or his politics. Edmund Burke governed his constitutional thinking on Lower Canada, but in 1831 he thought a moderate reform of parliament justified, a seeming paradox which Edward Ellice and Lord Durham [Lambton*] would have thoroughly understood. Like many upper-class Montreal Scots, he was a member of and generous patron to both the Presbyterian and the Anglican churches. In personality, he had much of the “state and distance” he so admired in Craig and which went well with his considerable height and majestic bearing. He was a man who wished to live by principles, and this desire often led to undue rigidity. He had the instincts of an outstanding team-player, although prone at times to define personally the true interests of the team. These instincts gave him superabundant energy and generated fierce and often selfless loyalties. Tragically, those who opposed his team, particularly Canadians, whose will to survive he could not fathom, whose loyalty to the Empire he could not accept, became enemies in his mind, which he spoke all too openly. Richardson did a great deal of good, but a great deal of harm also.

John Richardson may be the author of The letters of Veritas, re-published from the “Montreal Herald”; containing a succinct narrative of the military administration of Sir George Prevost, during his command in the Canadas . . . (Montreal, 1815).

AUM, P58, U, Richardson to Grant, 16 Aug., 25 Oct. 1819; Richardson to Gerrard, 22 April 1828; Richardson and Gregory to McIntosh, 18 Oct. 1830. NLS, Dept. of mss, mss 15113–15, 15126, 15139 (mfm. at PAC). PAC, MG 11, [CO 42] Q, 86–87, 107–9, 118, 132, 157, 161, 166, 168, 293; MG 23, GII, 10, vols.3, 5; 17, ser.1, vols.3, 9–10, 13–14, 16; GIII, 7 (transcripts); RG 1, E1: 29–36; RG 4, A1: 10262–44628; vols.141–47; RG 7, G1, 3: 259–69; 13: 42; RG 68, General index, 1651–1841. PRO, CO 42/127. SRO, GD45/3 (mfm. at PAC). “L’association loyale de Montréal,” ANQ Rapport, 1948–49: 257–73. “A British privateer in the American Revolution,” ed. H. R. Howland, American Hist. Rev. (New York), 7 (1901–2): 286–303. L. A. [Call Whitworth-Aylmer, Baronness] Aylmer, “Recollections of Canada, 1831,” ANQ Rapport, 1934–35: 305. Corr. of Lieut. Governor Simcoe (Cruikshank). “Courts of justice for the Indian country,” PAC Report, 1892: 136–46. Docs. relating to constitutional hist., 1759–91 (Shortt and Doughty; 1918); 1791–1818 (Doughty and McArthur); 1819–28 (Doughty and Story). Douglas, Lord Selkirk’s diary (White). L.C., House of Assembly, Journals, 1792–1815; Legislative Council, Journals, 1816–31; Statutes, 1793–1831. Mackenzie, Journals and letters (Lamb). L.-J. Papineau, “Correspondance de Louis-Joseph Papineau (1820–1839),” Fernand Ouellet, édit., ANQ Rapport, 1953–55: 191–442. Reports of cases argued and determined in the courts of King’s Bench and in the provincial Court of Appeals of Lower Canada, with a few of the more important cases in the Court of Vice Admiralty . . . , comp. G. O. Stuart (Quebec, 1834). John Richardson, “The John Richardson letters,” ed. E. A. Cruikshank, OH, 6 (1905): 20–36. Le Canadien, 1806–10, 28 May 1831. La Minerve, 21 févr., 6, 9 juin 1831. Montreal Gazette, 1787–1815; 1821–22; 28 May, 4, 11 June 1831. Montreal Herald, 1811–15. Quebec Gazette, 7 Aug. 1788; 26 May 1791; 21 June 1792; 21 Feb. 1793; 17 July, 11, 25 Dec. 1794; 5 Nov. 1801; 31 March 1803; 5 July, 27 Dec. 1804; 14 Nov. 1805; 2 Jan., 23 Oct. 1806; 2, 9 July, 12 Nov. 1807; 3 March, 12 May, 1 Sept., 24 Nov., 22 Dec. 1808; 1 June, 6 June, 30 Nov., 14 Dec. 1809; 4 Jan., 8, 29 March, 12 April, 17 May 1810; 18, 25 April, 16 May, 27 June, 18 July 1811; 28 May 1812; 28 May, 2 Sept. 1813; 11, 25 July, 28 Nov. 1816; 9 Jan., 22 May, 26 June, 2 Oct. 1817; 29 Jan. 1818; 18 Feb., 14 June, 5 Aug. 1819; 6 Jan., 27 April 1820; 12 April, 18 June, 25 July, 27 Aug., 22 Oct. 1821; 27 Nov. 1823. Quebec Mercury, 2 Feb. 1805, 2 May 1808. Quebec almanac, 1791: 84; 1796: 83. Roll of alumni in arts of the University and King’s College of Aberdeen, 1596–1860, ed. P. J. Anderson (Aberdeen, Scot., 1900). F. D. Adams, A history of Christ Church Cathedral, Montreal (Montreal, 1941). F.-J. Audet, Les députés de Montréal. A. L. Burt, The United States, Great Britain and British North America from the revolution to the establishment of peace after the War of 1812 (Toronto and New Haven, Conn., 1940). R. Campbell, Hist. of Scotch Presbyterian Church. Christie, Hist. of L.C. (1848–55), vols.1–3. D. [G. ] Creighton, The empire of the St Lawrence (Toronto, 1956). G. C. Davidson, The North West Company (Berkeley, Calif., 1918; repr. New York, 1967). Denison, Canada’s first bank. F. M. Greenwood, “The development of a garrison mentality among the English in Lower Canada, 1793–1811” (phd thesis, Univ. of B.C., Vancouver, 1970). Hochelaga depicta . . . , ed. Newton Bosworth, (Montreal, 1839; repr. Toronto, 1974). Innis, Fur trade in Canada (1970). H. E. MacDermot, A history of the Montreal General Hospital (Montreal, 1950). R. C. McIvor, Canadian monetary, banking and fiscal development (Toronto, 1958). Ouellet, Hist. économique; Lower Canada. R. A. Pendergast, “The XY Company, 1798–1804” (phd thesis, Univ. of Ottawa, 1957). K. W. Porter, John Jacob Astor, business man (2v., Cambridge, Mass., 1931; repr. New York, 1966). Robert Rumilly, La Compagnie du Nord-Ouest, une épopée montréalaise (2v., Montréal, 1980); Histoire de Montréal (5v., Montréal, 1970–74), 2. Taft Manning, Revolt of French Canada. Tulchinsky, “Construction of first Lachine Canal.” M. S. Wade, Mackenzie of Canada: the life and adventures of Alexander Mackenzie, discoverer (Edinburgh and London, 1927). J.-P. Wallot, Intrigues françaises et américaines au Canada, 1800–1802 (Montréal, 1965). M. [E.] Wilkins Campbell, McGillivray, lord of the northwest (Toronto, 1962); NWC (1973). R. H. Fleming, “The origin of Sir Alexander Mackenzie and Company,” CHR, 9 (1928): 137–55; “Phyn, Ellice and Company of Schenectady,” Contributions to Canadian Economics (Toronto), 4 (1932): 7–41. J. W. Pratt, “Fur trade strategy and the American left flank in the War of 1812,” American Hist. Rev. (New York), 40 (1935): 246–73. Henry Scadding, “Some Canadian noms-de-plume identified; with samples of the writing to which they are appended,” Canadian Journal (Toronto), new ser., 15 (1876–78): 332–41. Adam Shortt, “The Hon. John Richardson,” Canadian Bankers’ Assoc., Journal (Toronto), 29 (1921–22): 17–27. W. S. Wallace, “Forsyth, Richardson and Company in the fur trade,” RSC Trans., 3rd ser., 34 (1940), sect.ii: 187–94.

Cite This Article

F. Murray Greenwood, “RICHARDSON, JOHN (d. 1831),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/richardson_john_1831_6E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/richardson_john_1831_6E.html |

| Author of Article: | F. Murray Greenwood |

| Title of Article: | RICHARDSON, JOHN (d. 1831) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1987 |

| Year of revision: | 1987 |

| Access Date: | December 30, 2025 |