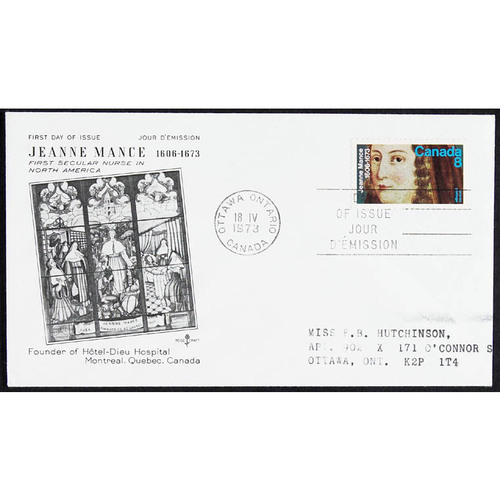

MANCE, JEANNE, founder of the Hôtel-Dieu of Montreal; b. at Langres in Champagne (France), baptized 12 Nov. 1606, daughter of Catherine Émonnot and Charles Mance, attorney in the bailliage of Langres; d. 18 June 1673 at Montreal.

The Mance family hailed from Nogent-le-Roi (today Nogent-en-Bassigny, Haute-Marne), and the Émonnot family from Langres, where Jeanne Mance’s parents went to make a home. The two families belonged to the administrative middle class; Charles Mance and Catherine Émonnot had married in 1602. They had six boys and six girls. Jeanne, their second child, was probably among the first pupils entrusted to the Ursulines, who had come to establish themselves at Langres in 1613. She was a little over 20 when she lost her mother. Very devout, and with the ability to be unmindful of herself, she became together with her sister the support of her father, and looked after the education of her young brothers and sisters. She experienced the hardships of the Thirty Years’ War, which spared scarcely any of the frontier towns of France. Hospitals were founded at Langres. The bishop, Sébastien Zamet, concentrated his efforts and poured out his gold for the construction of a charity-hospital in his town. Better still, he established a society of pious ladies directed towards charitable activities of an external and social nature. It was probably in this type of work that Jeanne Mance first served as a nurse. By it she no doubt learned to give emergency care to the wounded and the sick. How else can we explain her deftness at Ville-Marie, at the bedside of the horribly mutilated victims of the Iroquois? As her brothers and sisters grew up, she had more and more time to attend to charitable works, and her father was no longer there to require her care. He had died about 1635.

Around the middle of April 1640, Jeanne learned of the presence at Langres, where he was staying with her uncle Simon Dolebeau, of Nicolas, the eldest son of the Dolebeau family; he was the chaplain of the Saint-Chapelle in Paris and tutor to the Duc de Richelieu, the nephew of the Duchesse d’Aiguillon. Jeanne had a high regard for this cousin. She willingly followed his advice, although he was about her own age (he was born 18 Aug. 1605 at Nogent-le-Roi). Jeanne eagerly went to visit him. The young man spoke to her of New France. He could barely contain his emotion, for his younger brother Jean [see Dolebeau], a religious of the Society of Jesus, had just set sail for the missions in the colony. Nicolas also informed Jeanne that not only were courageous men of God hastening to those regions, but that since the summer of 1639 society women and nuns were landing there too, testifying to the same surge of faith and the same dauntlessness as their missionary companions. He described the astounding vocation of Mme de Chauvigny de La Peltrie and of the Ursulines whom she brought out to New France, and also that of the Hospitallers of Saint-Augustin sent there by the Duchesse d’Aiguillon. Dollier* de Casson, to whom we owe the account of these events, assures us that it was at that moment that Jeanne Mance felt for the first time the desire to go to New France.

A few days passed. Jeanne meditated and prayed. She decided to consult her director about her intention to sail for America. Whitsuntide was approaching. Her director, who is still unknown, urged her to submit all her aspirations to the scrutiny of the Holy Spirit. Finally the priest allowed her to sail for Canada. It was agreed that she should leave for Paris on “the Wednesday after Whitsun; that there she should go and see Father C[harles] Lalemant who looked after Canadian affairs, that as her director she should take the rector of the Jesuit house nearest to the place where she would be living.” She then spoke to her relatives and friends of her plans.

It was on the last day of May that Jeanne Mance left Langres. In Paris she went to the house of her cousin, Mme de Bellevue (née Antoinette Dolebeau, Nicolas’s only sister). Mme de Bellevue lived in the Faubourg Saint-Germain, not far from another of her brothers, Father Charles Dolebeau, a discalced Carmelite. Encouraged by the warmth of feeling shown to her, Jeanne abandoned her reserve. She spoke of her great missionary aspirations. She also zealously and punctiliously carried out the programme outlined for her by her director at Langres. She first presented herself at the Jesuit convent in Pot-de-Fer street (now Bonaparte). She saw Father Charles Lalemant, the procurator of the Canadian missions, who immediately took an interest in her plans. At the convent Jeanne also saw Father Jean-Baptiste Saint-Jure, whom the Society of Jesus, even at that time, considered one of its greatest masters. Unfortunately, for several months, it was impossible for Father Saint-Jure to receive her. In the meantime Jeanne immersed herself in the active life of charity led by her cousin. She made numerous acquaintances. Among others she was introduced to a great Parisian lady, Mme de Villesavin (née Isabelle or Isabeau Blondeau; wife of Jean Phélypeaux, seigneur of Villesavin). Jeanne did not suspect that in a few months this gracious lady would do her a remarkable service. For it was Mme de Villesavin who, one day, protested when she heard Jeanne regret not having had Father Saint-Jure’s advice as to her missionary aptitude. She promised Jeanne that she would plead her case before the religious, and she was successful; Jeanne was requested to go to the parlour as often as she thought fit. Other important women wished to make Jeanne’s acquaintance, notably Charlotte-Marguerite de Montmorency, Princesse de Condé, the wife of Chancellor Pierre Séguier, the Duchesse d’Aiguillon, the Marquise de Liancourt, Louise de Marillac, and Marie Rousseau, the celebrated Paris clairvoyante. Finally the queen herself, the devout Anne of Austria, expressed the desire to see her.

Dollier de Casson informs us that “a provincial of the Recollets, a man of great merit named Father Rapin, came to Paris; as she [Jeanne] knew him already she visited him and told him how things stood.” Father Rapine was glad to see Jeanne again. He was touched by her trust in Providence. Consequently, having approved her decision to go to Canada and work for the conversion of the Indians there, he added “that that was good, that she must forget herself in this way, but that it was well that others should take the necessary care of her.” A few days later, Father Rapine wrote to ask her to be good enough to go the Hôtel de Bullion, in Platrière street. There Jeanne met Father Rapine again; he introduced her to a distinguished and very wealthy lady, the discreet but bountiful protectress of the majority of French charitable works. This person was Angélique Faure, the widow of Claude de Bullion, the French superintendant of finance and a cousin of Father Rapine. Angélique Faure was the daughter of Guichard Faure de Berlise, a king’s secretary and master in ordinary to His Majesty, and of Madeleine Brulart de Sillery; the latter was the sister of Noël Brulart de Sillery, the founder of the Sillery mission in Canada, and of Nicolas, chancellor of France. From her union with Claude de Bullion, Angélique had had five children.

As these two great Christian women had made an excellent first impression on each other, Jeanne’s visits to the Hôtel de Bullion became more frequent. On the fourth occasion, Mme de Bullion asked Jeanne Mance “whether she would not consent to take charge of a hospital in the country to which she was going, because she proposed to found one there with what would be necessary for its maintenance, and on that account she would have been very glad to know what endowment was given to the hospital at Kebecq by Mad. Deguillon.” Jeanne raised some objections, but without rejecting the project absolutely. Mme de Bullion then requested her to be good enough to inquire about the approximate cost of the Hôtel-Dieu at Quebec, for she was prepared to give as much money for her hospital, if not more. Jeanne accepted. The Duchesse d’Aiguillon, she was informed, had allotted to the Hôtel-Dieu at Quebec a sum of 22,000 livres, which she raised a little later to a total of 40,500. Cardinal Richelieu, of course, had assumed responsibility for a part of these gifts. Meanwhile Jeanne went to the Jesuits and consulted Father Saint-Jure, to find out whether she should accept the offers made to her by Mme de Bullion.

After praying and meditating, Father Saint-Jure replied that she must go to Canada, “that it was infallibly Our Lord who wanted this association” with the wealthy lady. Mme de Bullion was delighted with Jeanne’s decision. She asked Jeanne to be sure, in the future, to maintain the most complete secrecy about all that concerned her, about her name, her person, and the gifts that she expected to make. Jeanne, deeply moved by such unselfishness, undertook to keep silent. On the last visit she made to the Hôtel de Bullion, she received a purse and other expensive gifts.

In April 1641 Jeanne took leave of her relatives and friends, and set off for La Rochelle. On her arrival she met the Jesuit Jacques de La Place, who informed her of the wonders that would attend the journey to New France. The next day Jeanne, on entering the church of the Jesuits, passed a gentleman. They exchanged a look charged with an extraordinary clairvoyance, for, in the words of the Véritables motifs, “no sooner had they greeted each other, without ever having seen or heard of each other before, than in an instant God implanted in their minds a knowledge of their inner selves and of their design that was so clear, that upon this mutual recognition they could not but thank God for His favours.”

This devout personage, in his forties, was Jérôme Le Royer de La Dauversière, a receiver of the taille at La Flèche, in Anjou, whom God had inspired with the project for Montreal in the cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris in 1635. Since that date he had developed his plan and obtained the approval of the Jesuits, his former masters at the Collège of La Flèche. In 1639, his efforts led to the founding of the Société Notre-Dame de Montréal, whose “Associates” acquired the island of Montreal. Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve was chosen to take charge of the new post.

M. de La Dauversière made urgent appeals to Jeanne. The Associates of Montreal needed a person of precisely her type, wise, devout, intelligent, and resolute, as bursar and later as nurse for the Montreal contingent. M. de La Dauversière obtained her consent as soon as she had consulted by letter first Father Saint-Jure, then Mme de Bullion. Jeanne then became a member of the Société Notre-Dame de Montréal.

On 9 May 1641 the contingent embarked on two ships. M. de Maisonneuve boarded one with a part of the contingent; the Jesuit father La Place, Jeanne Mance, and 12 men went aboard the second. But before the sails could be unfurled, M. de La Dauversière conversed for the last time with Jeanne. It was then that she suggested to him an extension of the Société de Montréal, which would, in her view, provide the support indispensable to their colonizing endeavours. She proposed that M. de La Dauversière should set down in writing an outline of the “Montreal project,” and deliver several copies to her. She would then address invitations to membership in the Société de Montréal to the distinguished and generous ladies and to the devout women with whom she had associated in Paris, and would attach to each invitation a copy of M. de La Dauversière’s draft. M. de La Dauversière promised to distribute the missives as soon as he reached Paris.

Jeanne Mance landed at Quebec at the beginning of August, the eighth, we are told by Dollier de Casson, who adds that “the ship carrying Mademoiselle Mance experienced little other than calm weather, M. de Maison-neufve’s encountered such violent storms that it had to put back to port three times.” The leader of the contingent apparently arrived at Tadoussac only on 20 September, when hope of his appearing that year was being abandoned.

The opposition manifested at Quebec against the founding of a post at Montreal, which was styled a “foolhardy undertaking,” dismayed Jeanne Mance. But M. de Maisonneuve, once he had got to his destination and been duly warned of this situation, decided to disregard it, although he did so with his usual courtesy. The founding was none the less postponed until the following spring because of the lateness of the season. Jeanne spent the winter at Sillery together with M. de Maisonneuve, Mme de La Peltrie, who displayed a keen affection for her, and M. Pierre de Puiseaux de Montrénault. The winter was marked by a few conflicts with the governor, Huault de Montmagny, who at the beginning was not in favour of the project of founding Montreal. In the face of M. de Maisonneuve’s firmness, he finally yielded. According to the Relations, the founding of Montreal took place 17 May 1642. On that date “Monsieur the Governor placed the sieur de Maison-neufve in possession of the Island, in the name of the Gentlemen of Mont-real, in order to commence the first buildings thereon.”

The founding of the Hôtel-Dieu at Montreal took place in the autumn of the same year. Here again it is a text of the Relations that fixes the date: “Of all the Savages, there remained with us [in the spring of 1643] but one, Pachirini. . . . he had always wished to live with us, together with two other patients, in the little Hospital which we had erected there [in the fort] for the wounded.” The construction of the hospital proper, however, took place only in 1645.

In 1649, Jeanne was at Quebec when some letters reached her from France. When she read them, she received, said Dollier de Casson, “three bludgeon strokes.” She learned from them first the death of Father Rapine, “who used to obtain for her, from his lady, all that was needed,” the lady being Mine de Bullion. She was likewise informed that M. de La Dauversière was seriously ill and was on the brink of ruin. Finally she was told that the Associates of Montreal had all dispersed. Jeanne decided to leave as soon as possible for France. She wrote to M. de Maisonneuve, acquainted him with the predicament of the Montreal post, and notified him of her immediate embarkation.

When she returned a year later, all the difficulties had been smoothed out. M. de La Dauversière had completely recovered and was concerning himself zealously with the interests of Montreal. The Société de Montréal had revived under the guidance of Jean-Jacques Olier, one of its founders. Finally Mme de Bullion, admirably well-disposed as ever towards Montreal and its hospital, had agreed with Jeanne upon a new method of communication which would allow her not to divulge her name.

But from the spring of 1651 on, the struggle against the Iroquois became more and more bloody and recurrent. “The Iroquois,” wrote Dollier de Casson, “having no more atrocities to commit . . . because there were no more Hurons to destroy, . . . turned their attention towards the île de Montreal . . . ; there is not a month in this summer when our book of the dead has not been stained in red letters by the hands of the Iroquois.” Jeanne Mance had to close the hospital and take refuge in the fort. All the settlers did the same. On the abandoned sites it was necessary to put garrisons; “we were getting fewer every day,” added Dollier de Casson.

At the end of the summer of 1651 M. de Maisonneuve, discouraged, and even profoundly distressed at the sight of settlers whom he loved and had undertaken to protect falling continually around him, resolved to bring an end to this slaughter at whatever cost. It was clear that they would all meet the same fate sooner or later. He would go to France, and try to obtain assistance in order to bring a good number of soldiers back to Ville-Marie. Or else, if he failed to gain the support of the Associates of Montreal, he would abandon the undertaking and order the settlers to return to France.

It was then that Jeanne intervened. Her trust in Providence had suddenly revealed to her the way to come to the assistance of all of them. She went to M. de Maisonneuve’s house and said to him that “she advised him to go to France, that the foundress had given her for the hospital 22,000 livres, which were in a certain place that she pointed out to him, – and that she would give him the money so that he could get help.” M. de Maisonneuve accepted the proposal in principle. Before making a final decision he wanted to pray, meditate, and consult the chaplains. He was also thinking about the way to compensate Mme: de Bullion for the loss of the capital that she was putting at his disposal. He sailed for France a few weeks later, not without some hope. By her advice to the governor, Jeanne Mance had just saved Montreal, for M. de Maisonneuve came back with help.

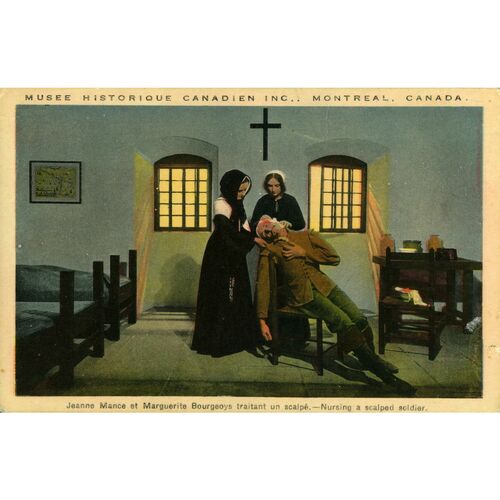

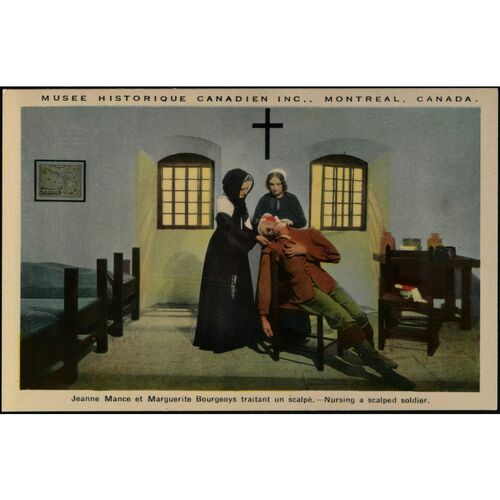

A few years later, 28 Jan. 1657, as she was returning from mass, Jeanne Mance fell on the ice, fractured her right arm, and dislocated her wrist. This fall had serious consequences. The doctors managed to set the fracture, but they failed to notice the condition of the wrist; although cured, Jeanne was unable to use her arm. Because of this infirmity she was obliged to consider having herself replaced as the head of the hospital. She waited, however, for the return of M. de Maisonneuve, who had set out for France again in 1655. He was to return only at the end of July 1657, together with the first parish clergy for Ville-Marie, which would consist of three Sulpicians under the leadership of Abbé Queylus [see Thubières]. But as ill luck would have it M. Olier, who had himself chosen these four missionaries, passed away just a few days before the priests went on board. Jeanne, who had lost no time in consulting M. de Maisonneuve on his arrival, had to postpone her journey to France until the following year. Her state of health left much to be desired. She set out in the autumn of 1658, together with Marguerite Bourgeoys, who had become her faithful friend. M. de Queylus had taken advantage of Jeanne Mance’s impending departure to send for two Hospitallers from Quebec. This was in accordance with a promise which he had made to the Hospitallers of Quebec, to entrust to them the management of the hospital at Montreal. The Quebec nuns were however obliged to go back to their convent when Jeanne Mance returned with the Hospitallers from La Flèche.

In France, Jeanne had to make the trip from La Rochelle to La Flèche on a stretcher. Her arm was giving her terrible pain. With M. de La Dauversière she made all the necessary arrangements, so that she could shortly take back to New France the three Hospitallers of Saint-Joseph whom he would himself choose. She confessed to him her hope of getting some funds from Mine de Bullion to help in establishing these nuns at Montreal. Her success was everywhere complete, and to it was even added an incident which has been considered as miraculous. In the Sulpicians’ chapel she had placed the relic of M. Olier’s heart on her injured arm, and had recovered the use of it. She re-embarked for New France with Mothers Judith Moreau de Brésoles, Catherine Macé, and Marie Maillet, and arrived in the colony 7 Sept. 1659. Marguerite Bourgeoys, with a few female companions, was on the ship. M. de La Dauversière, who had gone to La Rochelle, gave to all the women a final benediction. One of his most cherished wishes was being realized.

In 1662 Jeanne made her last journey to France. On this occasion an event of great importance had to be superintended: the replacement of the Société Notre-Dame de Montréal, which had withdrawn, by the Compagnie des Prêtres de Saint-Sulpice, which was becoming the seigneur and owner of the island of Montreal. The Société de Montréal was in the process of breaking up, and moreover M. La Dauversière, the tireless founder and providential benefactor of Ville-Marie, was no longer there to stir the Associates to action. He had died 6 Nov. 1659. Jeanne returned to Montreal in 1664.

From 1663 on, great changes had been taking place in the government of New France. Louis XIV had insisted on personally guiding the destinies of his overseas settlement. In the first place he had concerned himself with putting down the Iroquois. But since 1665 Ville-Marie had been plunged into the deepest affliction. M. de Maisonneuve had been requested to return to France on indefinite leave. No account had been taken of his 24 years of incomparable service. He had accepted this decision heroically, and he left New France in the autumn of 1665. Soon Jeanne Mance, too, encountered the inability of authorities whom she revered to understand her deeds of deliverance in earlier days. Ever courageous and resigned, she carried out her task to the end. Her last administrative act dates from January 1673. She died 18 June 1673 “in odour of sanctity,” affirmed Mother Juchereau* de Saint-Ignace in her Annales of the Hôtel-Dieu of Quebec.

A small picture signed L. Dugardin, preserved at the Hôtel-Dieu of Montreal, seems to represent the true face of Jeanne Mance. In any case one can read on the back of the work: “Authentic copy of the portrait of Mademoiselle Mance.” This inscription has been identified as probably being in the hand of Sister Joséphine Paquet, the archivist of the Hôtel-Dieu from 1870 to 1889.

Archives de l’hôtel de ville de Langres (Haute-Marne), Registres des baptêmes . . . de la paroisse Saint-Pierre et Saint-Paul. Dollier de Casson, Histoire du Montréal. JR (Thwaites). Juchereau, Annales (Jamet). Morin, Annales (Fauteux et al.). [Jean-Jacques Olier?], Les véritables motifs de messieurs et dames de la Société de Notre-Dame de Montréal pour la conversion des sauvages de la Nouvelle-France, éd. H.-A. Verreau (SHM Mémoires, IX (1880)). Daveluy, “Bibliographie,” RHAF, VIII (1954–55), 292–306, 449–55, 591–606; IX (1955–56), 141–49; Jeanne Mance, 1606–1673, suivie d’un essai généalogique sur les Mance et les De Mance par M. Jacques Laurent. (1ère éd., Montréal, 1934; 2e éd., Montréal et Paris, [1962]). [Étienne-Michel Faillon], Vie de Mademoiselle Mance et histoire de l’Hôtel de Villemarie en Canada (2v., Paris, 1854), Robert Le Blant, “Notes sur Madame de Bullion, bienfaitrice de l’Hôtel-Dieu de Montréal, après 1587–26 juin 1664,” RHAF, XII (1958–59), 112–25. Lefebvre, Marie Morin. Léo-A. Leymarie, “Les commencements de Montréal,” Cahiers Catholiques, 132 (1925), 3706–10. Mondoux, L’Hôtel-Dieu de Montréal. Louis-N. Prunel, Sébastien Zamet, évêque-duc de Langres, 1588–1655 (Paris, 1912). René Roussel, Le lieu de naissance et la famille de Jeanne Mance (Langres, 1932), extract from Société historique et archéologique de Langres Bulletin, X.

Cite This Article

Marie-Claire Daveluy, “MANCE, JEANNE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 2, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mance_jeanne_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mance_jeanne_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | Marie-Claire Daveluy |

| Title of Article: | MANCE, JEANNE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | April 2, 2025 |

![Melle Jeanne Mance. Fondatrice des Hospitalières de Montréal [image fixe] Original title: Melle Jeanne Mance. Fondatrice des Hospitalières de Montréal [image fixe]](/bioimages/w600.724.jpg)