Source: Link

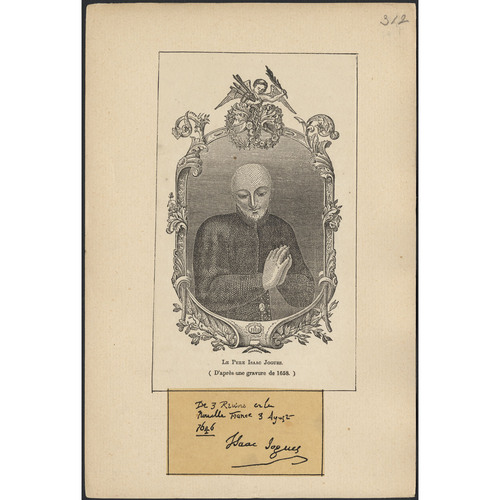

JOGUES, ISAAC, Jesuit, missionary among the Hurons and later among the Iroquois, ambassador for peace to the Iroquois; b. 10 Jan. 1607 at Orléans (France); murdered by the Iroquois 18 Oct. 1646 at Ossernenon (Auriesville, N.Y.); canonized 29 June 1930 with seven of his fellow martyrs.

The fifth of nine children, Jogues was born in a prosperous family that included notaries, lawyers, apothecaries, and merchants. He began his studies in the family home under the direction of a private tutor and continued them at the Jesuit college which had just been founded at Orléans in September 1617. He completed his courses at the age of 17. He could have taken up the flourishing business left by his father, or else he might, like his uncles, have chosen law or officialdom. But he preferred to follow his teachers, the Jesuits, and in October 1624 he was the first Jesuit from Orléans to enter the noviciate at Rouen, where he became a disciple of Father Louis Lallemant, an author of spiritual writings and a novice-master of repute. He made his first vows two years later and entered upon his studies in philosophy at the Collège at La Flèche, where the intense missionary spirit implanted there in 1613 by Father Énemond Massé still prevailed.

In 1634 Jogues began to study theology at Clermont (Paris), a celebrated institution that then numbered 2,000 students. He was at the same time the prefect responsible for discipline among the lay students. For reasons that are obscure, he was unwilling to continue the theological studies which his intellectual gifts would easily have allowed him to carry on. Indeed, he had always been studious; he had a thorough knowledge of Latin and Greek, and he expressed himself in a smooth flowery style that corresponded admirably to the courteous and refined manners of this renaissance gentleman. And yet he asked to be released from the rest of his studies. Was he perhaps impatient to set out for the American missions about which his reading of the Jesuit Relations had informed him?

Jogues’s ordination to the priesthood, which was conferred upon him at the end of January 1636 in the chapel of Clermont, brought all the closer his departure for the missions. His first mass, said in the church at Orléans on the first Sunday in Lent, brought joy mingled with sadness to his family. His mother consoled herself by preparing some priestly vestments and a few accessories, the only gifts that the missionary accepted for his crossing to the New World. The young priest, concluding his training, felt himself ever more deeply committed to his religious and missionary vocation. He detached himself from every worldly preoccupation, even those connected with his family, but did so with great delicacy and affection. The letters he wrote to his mother at this period and in subsequent years reveal him to us in his true light.

The departure, after several postponements, took place 8 April 1636. In the convoy of eight ships, Jogues took his place with Father Georges d’Endemare on the vessel that was to call at the Île de Miscou near Baie des Chaleurs. After eight weeks of sailing, the missionary arrived at this trading post which numbered 25 Frenchmen and 2 Jesuits. A week later he resumed his sea voyage, spending two days at Tadoussac where he made contact with the Indians, and then continuing towards Quebec, which he left immediately again to go on to Trois-Rivières. The sight of his colleagues Ambroise Davost and Antoine Daniel, emaciated and terribly aged after a few years of life as missionaries, made, a deep impression on him. He witnessed the torture of an Iroquois prisoner at the hands of Huron warriors. Despite the famous “important admonition” of Father Brébeuf, he could not remain unmoved. Still, his letters do not contain any evidence of fright; they exude only zeal and strength of character. He landed at Ihonatiria (Saint-Joseph I) on 11 September after 16 days’ travelling; he was given the name “Ondessonk” (bird of prey).

Jogues, who had been free of any illness during the crossing, was the first to be overcome by fever in September. The epidemics that raged among the Hurons at this period imperilled the lives of the missionaries, for the Indians believed them to be caused by the presence of the religious. In 1637 the situation became so acute that the Huron grand council decided upon the death of the priests. It was in that year that the missionaries met at Ossossanë for a farewell feast in Huron style, at which Brébeuf drew up the celebrated testamentary letter that all the Jesuits present signed. The epidemic ended without the execution of the death sentence. Some time before, 16 Aug. 1637, the first baptism had been administered to a Huron, Joseph Chihwatenha, a sublime spirit whose profoundly Christian temperament was to lend support to the missionary effort. His whole family followed his example on 19 March 1638.

The following August Father Jérôme Lalemant succeeded Father Brébeuf as superior of the Huron mission. The new superior, proceeding to reorganize the mission, decided to set up a central residence for the missionaries. The building of Fort Sainte-Marie was entrusted to Father Jogues. Subsequently the latter was sent with Father Garnier to the Tobacco nation. In September 1641, Jogues and Charles Raymbaut went into the territory of the Sauteurs (Chippewas). They pushed on a considerable distance to the west and came to the Sainte-Marie falls (Sault Ste. Marie). They were warmly welcomed, the meeting was a productive one, and the priests had to promise to come back to preach the gospel.

In June 1642 the Hurons were preparing a trading expedition to the French settlements, but the St. Lawrence River was under constant surveillance by the Iroquois between Ville-Marie (Montreal) and Trois-Rivières. Moreover the missionaries needed to replenish their supplies and to exchange news with Europe. Furthermore Father Raymbaut, gravely ill, required hospitalisation. Jogues was designated by Lalemant to accompany the convoy, which set off for Quebec. When their business was done, the travellers embarked for the return trip. They reached Trois-Rivières in the last few days of July. In addition to Jogues, the group included Guillaume Couture*, the donné René Goupil, another Frenchman, and some Hurons, one of whom was Ahatsistari; in all there were about 40 persons divided among 12 canoes. The party finally got under way 1 Aug. 1642. The day following their departure, the canoes were craftily attacked by some Iroquois in ambush. Historians are not entirely agreed on the location of the attack. Be that as it may, it must have occurred around Sorel, around Berthier, or, more likely around Lanoraie. After a brief exchange of gunfire, Jogues, Goupil, Couture, and a group of the Hurons were carried off as prisoners into Mohawk territory and put to the most appalling tortures: floggings, bites, mutilations, strippings, forced marches, and insults.

The moral anguish, even more acute than the physical torment, Jogues bore with extraordinary fortitude. He endured it all the more fondly because he had sought it out. For, as he himself assures us, he had cast himself into the hands of the Iroquois of his own free will. “I was watching this disaster,” says the father, “from a place very favorable for concealing me from the sight of the enemy, being able to hide myself in thickets and among very tall and dense reeds; but this thought could never enter my mind. ‘Could I, indeed,’ I said to myself, ‘abandon our French and leave those good Neophytes and those poor Catechumens, without giving them the help which the Church of my God has entrusted to me?’ Flight seemed horrible to me; ‘It must be,’ I said in my heart, ‘that my body suffer the fire of earth, in order to deliver those poor souls from the flames of Hell; it must die a transient death, in order to procure for them an eternal life.’ My conclusion being reached without great opposition from my feelings, I called the one of the Hiroquois who had remained to guard the prisoners.”

René Goupil was killed (29 Sept. 1642) by an Iroquois in front of Jogues, who was kept captive under constant threat of death until November 1643. An old Iroquois woman had adopted him and he acted as a servant. He had been so weakened by blows and hardships that the only work he could do was a task reserved for women: gathering wood to feed the fire in the lodge on the hunt.

With the complicity of the Dutch, Jogues embarked at the beginning of November 1643 on a ship that reached England at the end of December. He took another ship and the next day, Christmas Day, he disembarked on the coast of Brittany. Finally, 5 Jan. 1644, he reached the nearest Jesuit house, the Collège at Rennes. His superiors were unable to recognize him, so transformed was he by his sufferings and mutilations. He took some rest in order to recover from his fatigue and pain, attempting to hide from the admiration that people wanted to lavish on him. He was obliged, however, to yield to the entreaties of the queen regent, Anne of Austria, who insisted upon beholding this martyr. Before her and before Mazarin and the directors of the Compagnie des Cent-Associés, he bore witness to the wretchedness and the needs of New France.

While he was in France, steps were taken to seek from the pope an indult that would permit Jogues to celebrate mass despite his mutilated fingers. The sovereign pontiff readily granted him this favour, believing that it was not proper that a martyr for Christ should not be able to offer Christ’s blood (“Indignum esset Christi martyrem Christi non bibere sanguinem”).

In the colony nothing was yet known of Jogues’s fate, and his escape was learned of only when he landed at Quebec early in July 1644. Despite the torment he had suffered, he eagerly sought from his superiors the privilege of devoting himself to the evangelizing of the Iroquois. But peace had not been restored among the Mohawks, and Father Vimont preferred to assign Father Jogues to the post at Ville-Marie, founded two years earlier. This was to be a calmer period for Jogues, which would allow him to compose various important texts for posterity: the account of his captivity and that of the death of his companion Goupil, and what may be considered the earliest description of New York.

Peace, of which there was still no sign on the Iroquois side, finally came about following the freeing of Father Bressani in August 1644. Exchanges of prisoners, as proposed by Governor Huault de Montmagny, encouraged negotiations. Jogues became an important personnage when he appeared before the council meeting held by the governor at Trois-Rivières 12 July 1645, in the course of which the Mohawk orator Kiotseaeton played a prominent part. From 15 to 25 September, a new council brought confirmation of the peaceful intentions of the Mohawks, but the French persisted in having serious doubts about their good faith.

As soon as Father Jérôme Lalemant was appointed superior-general of the Jesuits in New France, Jogues again expressed his desire to go and work for the evangelizing of the Iroquois. But the guarantees of peace were not yet sufficiently firm, and were built up only gradually during the councils held on 22 Feb. and 13 May 1646. Jogues was then accepted by Father Lalemant and by the governor as an ambassador for peace to the Mohawks. The joy with which Jogues received the news of his appointment was tinged with very justifiable misgivings. To Father Jérôme Lalemant he made this reply: “Would you believe that, on opening the letters from your Reverence, my heart was, as it were, seized with dread at the beginning, apprehending lest what I desire, and what my spirit should most prize, might happen. Poor nature, which remembered the past, trembled; but our Lord, through his goodness, has calmed it and will calm it still further. Yes, my Father, I desire all that our Lord desires, at the peril of a thousand lives. Oh, what sorrow I would have, to fail at so excellent an opportunity! Could I endure that it should depend on me that some soul were not saved? I hope that his goodness, which has not forsaken me on [past] occasions, will assist me still; he and I are able to trample down all the difficulties which might oppose themselves.” The missionary took thought for immediate preparations for his future apostolate by bringing together a box of warm clothes for the winter, the sacred vessels for masses, and gifts for the Indians.

After leaving Trois-Rivières 16 May 1646, the expedition ascended the Richelieu and crossed Lake Champlain. Jogues was the first white man to see Lake George, which he named Saint-Sacrement, as his companion Jean Bourdon noted on his map. The Mohawks were intrigued by the mysterious box that Jogues wanted to leave with them. At the conclusion of the parleys, the diplomats set out on the return trip on 16 June, called at Fort Richelieu on 27 June, at Trois-Rivières on 29 June, and arrived at Quebec on 3 July. Jogues gave an account of his mission to the authorities, who once again refused to allow him to leave to spend the winter among the Iroquois. Having returned to Montreal, Jogues was recalled at the end of August to Trois-Rivières, where the peace council authorized him to take part in a new embassy being planned by the Hurons. This time Jogues had decided to stay the winter. He left on 24 September with Jean de La Lande and with the Hurons, who abandoned them at Fort Richelieu. The two Frenchmen pushed on with a single Huron. They met a hostile reception; towards the middle of October, they were taken prisoner. The feeling of the Iroquois had completely changed because, mystified by the small box left at the Mohawk village by Jogues, they saw in it the confirmation of their suspicions about the cause of the epidemic, the drought, and the famine that had followed his summer embassy. On 18 October, at Ossernenon, Jogues was killed by a hatchet blow in the head. La Lande perished in the same way, probably the next day.

Parkman has asserted that Jogues might truthfully have aspired to literary fame. It has even been said that in him the humanist could die only with the saint, so completely did his intellectual qualities complement his spiritual ones and thus give him his maximum value as a writer. Like several of his fellow missionaries in New France, he was a mystic, but in one sense he surpassed them all because he knew how to express the experience that he, like them, had previously undergone. His spiritual writings, equally as limpid as those of Father Brébeuf, surpass the latter’s by a lyricism which achieves great literary perfection. He controls his pen as readily as he disciplines his sensibility, his memory, and all his faculties. Even in the depths of grief, he never bursts out, but makes us feel that he is aware of living through an adventure that overpowers him, but does not crush him. The truth is that under a timid and frail exterior he concealed an astonishing fortitude and spiritual independence. He was a sensitive person, fired with love, whose interior joy never yielded to grief. Divine love had once and for all enveloped his whole being.

ACSM, “Mémoires touchant la mort et les vertus des pères Isaac Jogues . . .” (Ragueneau), repr. APQ Rapport, 1924–25, 3–41, passing; various autographed writings and apographes by Jogues, including a note on René Goupil (May 1646) and several letters. JR (Thwaites); an important printed source, with bibliographical information. Lettre du père Jogues, captif chez les Iroquois, au gouverneur de Montmagny,” BRH, XXXVI (1930), 48–49. Positio causae. John Joseph Birch, The saint of the wilderness: St. Isaac Jogues (New York, 1936). BRH, V (1899), 88–90; XVIII (1912), 91. Lucien Campeau, “Un site historique retrouvé,” RHAF, VI (1952), 31–41. Charlevoix, Histoire, I, 232–77. N.-E. Dionne, “Le père Jogues et les Hollandais,” BRH, X (1904), 60–4. Jésuites de la N.-F. (Roustang). Louis-Raoul de Lorimier, “Jogues (en marge de l’histoire, 1607–1646),” RC, XIX (1917), 336–51. Lucien Lusignan, “Essai sur les écrits de deux martyrs canadiens,” BRH, L (1944), 174–92. Félix Martin, Le R.P. Isaac Jogues de la Compagnie de Jésus, premier apôtre des Iroquois (Paris, 1873). Henri Petiot [Daniel-Rops], Les aventuriers de Dieu (Paris, 1951), 121–42. Rochemonteix, Les Jésuites et la Nouvelle-France au XVIIe siècle, I, II, 429–43. Francis Talbot, Saint among savages (New York and London, 1935); Un saint parmi les sauvages (Paris, 1937). W. H. Withrow, “The adventures of Isaac Jogues, s.j.,” RSCT, 1st ser., III (1885), sect.ii, 45–53.

Cite This Article

In collaboration with Georges-Émile Giguère, “JOGUES, ISAAC,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 25, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jogues_isaac_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jogues_isaac_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | In collaboration with Georges-Émile Giguère |

| Title of Article: | JOGUES, ISAAC |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | November 25, 2024 |