Source: Link

BRESSANI, FRANÇOIS-JOSEPH (Francesco-Giuseppe), priest, Jesuit, missionary; b. 6 May 1612 in Rome; d. 9 Sept. 1672 in Florence.

Bressani entered the Society of Jesus 15 Aug. 1626, at the age of 14. He held in succession the chairs of literature, philosophy, and mathematics. Like so many others he was attracted by the foreign missions, and sought the privilege of being sent to New France. His superiors granted his wish in 1642. He first spent some time at Quebec in order to adapt himself; from there he went to Trois-Rivières (1643), a post much frequented by the Indians during the summer months. The missionary aspired to more arduous tasks; he obtained permission to penetrate 900 miles into the interior of the country, where the Hurons lived.

On 27 April 1644, as soon as the snows melted, he set out, together with one Frenchman and six Christian Hurons. He did not know that some ten bands of Iroquois were in ambush at strategic points on the route followed by the convoys of the French or those of their allies. Seven or eight miles from Fort Richelieu, when they were on their third day of travel, Father Bressani and his companions were attacked by a band of 27 Iroquois. The assailants took them prisoner, and dragged them by short stages towards their tribal territory, which they reached on 30 May. Father Bressani, weakened and mutilated, was only at the beginning of his sufferings. He bore stoically the most savage tortures; on 19 June, when he was awaiting death, his torturers handed him over to an old Iroquois woman, to replace her grandfather who had earlier been murdered by the Hurons. This unexpected outcome gave him a little respite and enabled him to write a long letter to the general of the Jesuits. This document, taken from the Breve Relatione, is dated 15 July 1644, and recounts in detail the sufferings he underwent. It opens with these lines: “I know not whether Your Paternity will recognize the letter of a poor cripple, who formerly, in perfect health, was well known to you. The letter is badly written and quite soiled, because, in addition to other inconveniences, he who writes it has only one whole finger on his right hand; and it is difficult to avoid staining the paper with the blood which flows from his wounds, not yet healed; he uses arquebus powder for ink, and the earth for a table.”

The captive could not be the slightest use to the old woman, who got rid of him by turning him over to the Dutch for a trifling ransom. The religious was well treated, and was able to return to France: he reached the port of La Rochelle 15 Nov. 1644. He asked to go back to New France. In July 1645 he was once again at Trois-Rivières, where he took part in the peace palavers of an Iroquois delegation, fraternizing with his former torturers. In the autumn of the same year, he started out again for the Huron country.

The Huron missions, continually harassed by the Iroquois, lived in terror. The situation was such that in 1648 the decision was made to appeal to Governor Huault de Montmagny. Father Bressani, at the head of 250 Hurons, was to go and ask for help. The assemblage arrived at Quebec at the end of July 1648. All that the governor could do was to grant an escort of 12 soldiers; the Jesuits sent a few religious as reinforcements. The fleet of 60 canoes, bringing back the 250 Hurons and 26 Frenchmen, reached the Huron country without mishap. Father Bressani was dumbfounded to hear that during his absence the Iroquois had wiped out the village of Saint-Joseph (Teanaostaiaë), murdered Father Antoine Daniel, and killed more than 700 Hurons. This was only a beginning. On 6 March 1649, when the winter was scarcely over, the Iroquois reappeared, and ruthlessly massacred both Hurons and missionaries. The powerful Huron nation was reduced to a few hundred fugitives, whom the missionaries took to the Île Saint-Joseph (Christian Island), in order to give them temporary asylum. Help had once again to be sought from Quebec. Once more Father Bressani was instructed to go and plead the cause of the Huron missions, before the new governor Louis d’Ailleboust . He was received with kindliness, but obtained no formal promises. The governor could not withdraw his troops from the posts on the St. Lawrence. The missionary wanted to return to his flock immediately, and he left Quebec with a few Hurons on 28 Sept. 1649. His journey was a wildly imprudent venture, and the Hurons forced the father to turn back at the Rivière des Prairies, in the vicinity of Montreal. He returned reluctantly to Quebec, but was to leave again for the Huron country in June 1650 with a flotilla of some 23 canoes, carrying about 30 Frenchmen and 30 Indians, including J.-B. Atironta. Meanwhile, after painful deliberation, the missionaries in the Huron country had decided that it was impossible to maintain their position in that region, and that it was better to bring back to the St. Lawrence the few hundred Hurons who had escaped the massacre. Father Paul Ragueneau was leading a group of 300 survivors towards Quebec in the summer of 1650 when he met the rescue column led by Father Bressani. They had to go back to the capital (28 July 1650).

All the missionaries from the Huron country were available for new duties. The superior decided to send some of them back to France, to await better times. Father Bressani was among them. He sailed 2 Nov. 1650. He returned to Italy and devoted himself to preaching and to his apostolate.

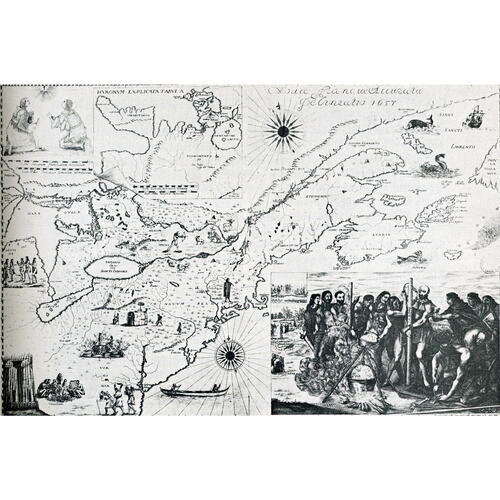

During his eight years of evangelizing in Canada, Father Bressani had acquired valuable experience of the country and its inhabitants. He recorded his discoveries and observations in a work devoted principally to the Huron country and its martyrs. The Relation abrégée of Bressani, written in Italian, has been translated into French by Father F. Martin, a Jesuit.

[F.-J. Bressani], Relation abrégée de quelques missions des pères de la Compagnie de Jésus dans la Nouvelle-France par le R. P. Bressany de la même compagnie, ed. Félix Martin (Montréal, 1852). JR (Thwaites). JJ (Laverdière et Casgrain). “Une lettre inédite du R. P. Bressani,” BRH, XXXVIII (1932), 546–47. Rochemonteix, Les Jésuites et la Nouvelle-France au XVIIe siècle, II, 36–37. Yvon Thériault, L’apostolat missionnaire en Mauricie (Trois-Rivières, 1951), 37–44.

Cite This Article

Albert Tessier, “BRESSANI, FRANÇOIS-JOSEPH (Francesco-Giuseppe),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bressani_francois_joseph_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bressani_francois_joseph_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | Albert Tessier |

| Title of Article: | BRESSANI, FRANÇOIS-JOSEPH (Francesco-Giuseppe) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | April 28, 2025 |