DOUGLAS, THOMAS CLEMENT (known as Tommy Douglas), printer, Baptist minister, and politician; b. 20 Oct. 1904 in Falkirk, Scotland, first of the three children of Thomas Douglas, an iron moulder, and Annie Clement; m. 30 Aug. 1930 Irma May Dempsey (1911–95) in Brandon, Man., and they had two daughters, one of whom was adopted; d. 24 Feb. 1986 in Ottawa and was buried there in Beechwood Cemetery.

In 2004 the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation took a popular poll to determine the “Greatest Canadian” as part of its television series of the same name. Tommy Douglas finished first, in a top ten that included cultural icons Terrance Stanley Fox and Wayne Douglas Gretzky and prime ministers Sir John A. Macdonald*, Lester Bowles Pearson*, and Pierre Elliott Trudeau*. The result may seem surprising. Why would Douglas, a premier of Saskatchewan and leader of a small federal party, be held in higher esteem than any other Canadian?

The answer lies in Douglas’s instrumental role in shaping the country’s most cherished social program, medicare, and in the personal characteristics that made him such an influential figure. Most important was his powerful moral impulse to change the status quo to improve the lives of the working poor and the disadvantaged. He also had a keen sense of what could be accomplished in the context of his time and circumstances, which allowed him to pursue a philosophy best understood as pragmatic idealism. To these should be added a self-awareness that made him realize his own fallibility of judgement, an ability to attract and make effective use of talented people, a natural pugnacity that was perfectly suited to the adversarial arena of politics, a relentlessness in the pursuit of major policy change, and a stubborn perseverance that allowed him to recover from defeats and fight another day. Perhaps his most memorable trait was his regular use of humour to win friends and keep allies, as well as to ridicule political foes.

Douglas was born in Falkirk, Scotland, on the outskirts of industrial Glasgow, on 20 Oct. 1904. His first name came from his father, Thomas, and his middle name from his mother, Annie Clement. In April 1911 Thomas emigrated to Winnipeg to find a more promising future for his family. The following spring Tommy, his mother, and his two sisters arrived in the city. The family lived in a series of rented houses in the North End, near the Vulcan Iron Works, where his father was employed. In September 1912 Tommy began attending what he later called “a little Norquay Street school,” close to the All Peoples’ Mission. There Tommy found a place to swim, play sports, and meet other poor immigrant children, many of whom had come from outside the British empire and knew only rudimentary English. It was in these years that Tommy first encountered Methodist minister James Shaver Woodsworth*, the mission’s superintendent, who would later become leader of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF).

As a young lad, Tommy had injured his knee in a fall, and an ensuing bone infection, known as osteomyelitis, caused him persistent pain. A Scottish doctor had scraped the femur of that leg on the family’s table in Falkirk, but the treatment proved ineffective. In Winnipeg, Tommy was able to attend school one winter only because two neighbourhood boys of eastern European descent pulled him there on a sleigh. After a long bout of hospitalization, he was slated to have his leg amputated until Dr Stanley Alwyn Smith, an orthopaedic surgeon at Winnipeg’s Children’s Hospital, agreed to perform an expensive and complicated corrective procedure for free as part of a clinical experiment for educational purposes. Tommy would be intermittently plagued by pain for the rest of his life, but the operation saved his leg. He would later cite this experience as a reason why medical care should be a social good – a right of citizenship – rather than something given sporadically as charity or sold as a commodity.

In April 1916 Tommy’s father joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force to fight in World War I. After he was sent overseas, the family moved to Glasgow to be closer to him. Tommy went to school, and to help his parents he worked four hours each weekday and all day Saturday as a soap boy in a barber shop. In the summer of 1918, at age 13, he got a job at a cork factory and was soon promoted, becoming the owner’s office assistant. That fall Tommy quit school to work at the factory full-time. His father came home after the armistice and decided that the family should return to Canada, where he would join them after his discharge. Tommy later remarked that he believed his father’s negative reaction to the entrenched class differences in the old country had fuelled his eagerness to leave.

In January 1919 Tommy Douglas, his mother, and his sisters made their way back to Winnipeg. He became an apprentice printer, setting linotype for the Grain Trade News. On 21 June, “Bloody Saturday” of the Winnipeg General Strike [see Mike Sokolowiski*], he witnessed mounted policemen charging at protesters on Main Street and shooting into the crowd. His sympathies lay with the strikers, as well as with Woodsworth, who was jailed on the charge of seditious libel for his editorials in the pro-worker Western Labor News.

Douglas’s interest in religion blossomed at this time and he frequented various church groups. Following in his mother’s footsteps, he embraced the Baptist faith. In his spare time he gave talks at the local church, and he was a part-time preacher. He joined and then became a chaplain in the Order of DeMolay, which had recently been established for young men who were loosely associated with freemasonry. Interested in acting, Douglas found an outlet in DeMolay monologue performances. A member of the order noticed his talent and convinced him that he should consider attending university after finishing his five-year printing apprenticeship.

While most of his time after work was connected to church-related activities, Douglas also took up boxing at the One Big Union gym. He was short in stature and extremely thin, but he became a very good fighter, winning the lightweight championship of Manitoba in 1922 and 1923. The sport provided Douglas with an outlet for his adversarial nature that only politics would replace; decades later he instinctively squared off like a boxer when debating opponents. Yet he was more drawn to the religious life: soon after defending his title in 1923, he quit boxing and resolved to become a full-time preacher.

In the fall of 1924 Douglas enrolled at Brandon College, where he was to spend six years studying for the degree necessary to become a Baptist minister. The first three involved completing the high-school education he had skipped while working to help support his family during the war. He paid his way through college by filling in as a relief preacher in rural Manitoba, mainly in the summers. This experience gave him considerable insight into the culture and psychology of rural voters in the prairies.

At Brandon College, Douglas was taught by a group of liberal-minded professors who espoused the Social Gospel at a time when the controversy between Baptist progressives and fundamentalists was at its high point. He was impressed by his professors’ arguments, which made him aware of the limits of the fundamentalist beliefs of many Baptists. Douglas was most influenced by Harris Lachlan MacNeill, who taught Greek, Latin, and the New Testament, and who rejected literalist interpretations of the Bible. Douglas later recalled: “He took the position that the Bible was a library made up of poems like the Psalms, drama like the Book of Job and the Book of Esther, historical books, letters such as the Epistles of St. Paul, and prophecies and actual biographical accounts like the Gospels. He thought that each of these should be interpreted in the light of the purpose for which they were written.” MacNeill’s views would stick with Douglas, who became fond of comparing the Bible to a “bull [double bass] fiddle,” in the sense that “you can play any tune you want on it.”

His final year at Brandon College (1929–30) was highly rewarding. That fall the institution asked Douglas and classmate Stanley Howard Knowles* to provide weekend relief preaching at Calvary Baptist Church in Weyburn, Sask. In the process, they were each auditioning for a permanent position there. (Although they were vying for the same job, their rivalry was not quite as fierce as has been suggested by some biographers.) Tommy had considerable experience as a relief preacher, and he impressed the congregation in Weyburn with his dramatic yet down-to-earth style, which was saturated with a sense of humour perfectly suited to a small rural town. He was selected with great enthusiasm as the congregation’s pastor.

Douglas first encountered Irma Dempsey while doing relief preaching in Carberry, Man. He then became reacquainted with her after she began attending Brandon College as a music student, and they were on opposing sides in an intravarsity debate. His team uncharacteristically lost the contest, but he won a companion. They married in the summer of 1930 – he was 25 years old and she was 19 – soon after he was ordained a Baptist minister. Irma was won over by Tommy’s zest for life and quick wit. Theirs was to be a life partnership. The couple would have two daughters: Shirley Jean*, born in 1934, and Joan, whom they adopted in 1945. Irma, in her quiet and even shy way, supported Tommy as an activist minister and workaholic politician, and she felt his disappointments and defeats as keenly as he did. She zealously protected his privacy in the little time he had to rest. Joan later recalled, “Mom built him not only a castle, but almost a fortress. Nothing was allowed to disturb him at home, she organized everything from major repairs down to being sure his clothes were clean and ready whenever he wanted.”

In the summer of 1930 Douglas took up his ministry in Weyburn, a farming community in the southeast corner of the province, within the semi-arid Palliser’s Triangle [see John Palliser*]. Douglas arrived shortly after the onset of the Great Depression, during which a precipitous decline in wheat prices, coupled with drought, devastated local farms and resulted in the closing of many other businesses. Douglas valued traditional practices, such as prayer meetings and revivals, that met the spiritual needs of his parishioners. At the same time, his progressive leanings led him to do more than simply preach charity from the pulpit. He worked with ministers from other congregations, for example, to get clothes and food shipped in for the desperate farm families in the region. His church’s basement filled with donations, which he then distributed to the needy. He and Irma organized charity drives to help poor residents in Weyburn and the surrounding rural areas whether or not they belonged to the congregation.

In 1931, while living in Weyburn, Douglas began to work part-time on an ma from McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont., and a doctoral degree in sociology at the University of Chicago. That summer he obtained leave from Calvary Baptist Church to study in Chicago. For a course in Christian sociology he was sent to investigate America’s largest depression-era slum, the “hobo jungle,” where some 75,000 unemployed men had built a vast makeshift settlement that was a city unto itself. His experience there would have a permanent impact on his political philosophy. In a 1958 interview Douglas described his time in Chicago as a major turning point in his life, “when I began to read and think and inquire,” and came to radical conclusions:

It was true that I had known Mr. Woodsworth, and had been interested in the Labour party in Winnipeg, and my father had belonged to the Labour party in the old country, but I had never sat down seriously and asked what’s wrong with this economic system of ours until it actually broke down. I was like a lot of other people who had taken only an academic interest in this question. We had a course in economics at [Brandon] university. I’d studied socialism and syndicalism and guild socialism, and communism and capitalism. But I’d never sat down and honestly asked myself what was wrong with the economic system. I think most people in the church were exactly the same. We’d taken it for granted. We’d accepted it. But here we were facing poverty, misery, want, lack of medical care, and lack of opportunity for a whole generation of young people who were frustrated and denied their right to live a normal decent life.

Douglas returned to Weyburn a changed man. Concluding that charity was insufficient, he used his position at Calvary Baptist Church to help the poor and destitute through direct action. He established a labour exchange that allowed skills to be bartered by people who were short of cash, and a club to provide boys from poor families with direction and hope. He also helped organize the Weyburn Independent Labour Association to influence public opinion in favour of unemployment insurance, the equal rights of citizens, and public ownership of basic utilities. Controversially, in September 1931 he supported the demands of the Mine Workers’ Union of Canada during a protracted coal strike in Estevan, a town southeast of Weyburn. On the 18th he publicly spoke to the miners, and in his Sunday sermon two days later he asked his congregation: “Would Jesus revolt against our present system of graft and exploitation? How would Jesus view the coal miners’ strike in Estevan?” Douglas’s answers were made clear by the sermon’s title, “Jesus the revolutionist.” He also organized a supply of food for the miners and their families, an action hardly designed to please pro-business members of the church. On the 29th he witnessed a confrontation between police and the strikers that left three miners dead and many more injured.

In the summer of 1932 Douglas again took leave from his ministry, this time to pursue courses in economics at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg. The following year he earned his ma in sociology from McMaster. His thesis, “The problems of the subnormal family,” was based on his research on 12 prolifically reproductive, “mentally subnormal” women, at least some of whom he had studied at the Weyburn mental hospital [see Robert Menzies Mitchell*]. Douglas recommended the segregation of families such as theirs from the general population, and sterilization in extreme cases. Such views were held by many progressive reformers, including Helen Letitia McClung [Mooney*]. However, Douglas would have a change of heart even before the end of World War II, when the full revelation of Nazi Germany’s race-based exterminations spurred the widespread repudiation of eugenics. Soon after becoming premier of Saskatchewan in 1944, he rejected the advice of two experts who promoted eugenic-style programs, and instead adopted various measures to improve the province’s mental-health system.

Douglas joined the socialist Co-operative Commonwealth Federation shortly after the party was created in 1932. He attended its founding conference the following year but was not a principal author of the Regina Manifesto, which he later came to feel was too uncompromising in its call for public ownership of the economy. In his view the CCF never intended to eliminate private ownership, either of the small farms that were the economic lifeblood of the prairie provinces or of the cooperatives that had sprung up throughout Saskatchewan after World War I. The Regina Manifesto, however, seemed to suggest the opposite, pledging that “No C.C.F. Government will rest content until it has eradicated capitalism.” The result was that, as Douglas saw it, the party made itself unnecessarily vulnerable to the charge that present and future CCF governments “wanted to own all businesses, even including farms,” a charge that he believed hindered all candidates under the CCF banner.

In the general election of 19 June 1934 Douglas stood in Weyburn as a candidate for the Farmer-Labour Party, as the CCF’s provincial wing was initially known in Saskatchewan. During the campaign his party’s literature was circulated to immigrant families in their own languages, mainly Ukrainian, Russian, and German. This tactic made little difference: Douglas came in third, well back of the winning Liberal candidate and just behind the Conservative incumbent. The Liberal Party, in particular, was effective in convincing immigrant voters that the CCF intended to expropriate all private farmland, as the Communist Party had done in the Soviet Union.

With the Great Depression worsening, Douglas became ever more radicalized. He saw the economic order as unjust, and criticized not only capitalists, but also the established political parties and churches, which in his view supported this unfair system. In June 1934 the journal Research Review (Regina) published a recently delivered speech that captured his sentiment about Christianity and his belief in the need to build what he would later term “a New Jerusalem on earth”:

The religion of tomorrow will be less concerned with the dogmas of theology and more concerned with the social welfare of humanity.… When one sees the church spending its energies on the assertion of antiquated dogmas … but dumb as an oyster to the poverty and misery all around, we cannot help recognize the need for a new interpretation of Christianity.…

[We have] come to see that the Kingdom of God is in our midst if we have the vision to build it. The rising generation will tend to build a heaven on earth rather than live in misery in the hope of gaining some uncertain reward in the dim distant future.

Douglas ran as the CCF candidate for Weyburn in the federal election of 14 Oct. 1935. Drawing lessons from his defeat the year before, he aimed to mobilize as much of the anti-Liberal vote as possible. To this end he spoke sympathetically about the aims of Social Credit, a new party that had recently become the government in Alberta under the leadership of William Aberhart*. Douglas managed to gain this party’s endorsement, thereby avoiding vote-splitting between the CCF and Social Credit that might have benefited the Liberals. The strategy worked: Douglas squeaked out a win over the Liberal incumbent in Weyburn, while most other CCF candidates across the country were defeated. However, many CCF members resented that he had accepted the endorsement of a rival party, and after the election Douglas was censured by the CCF’s national executive, but not ejected from the party. Though he would be dogged for a few years by the controversy, it was largely forgotten by the time he became premier of Saskatchewan in 1944.

While keeping his domicile in Weyburn, Douglas now had to get a place to live in Ottawa. His career as a full-time preacher had come to an end. He later recalled that while he was debating whether to run in 1935 a conservative Baptist superintendent had told him, “If you don’t stay out of politics, you’ll never get another church in Canada, and I’ll see to it.” (True to his combative nature, Douglas had replied, “You’ve just given the C.C.F. a candidate.”) In fact, he stayed on as a reserve minister and preached on special anniversaries. He continued to see politics in moral terms and regarded socialism as an extension of the most basic teachings in the New Testament. In his view there was no inevitable conflict between progressive politics and organized religion, and he would never break his ties with the Baptists, unlike J. S. Woodsworth, who had broken with the Methodists. At the same time, Douglas sought to avoid mixing religion and politics.

The CCF’s five-member caucus lacked influence in the House of Commons, but Douglas stood out for his great speaking ability and flair for the theatrical. He focused on two main subjects as an opposition critic: the plight of western farm families and Canada’s role in foreign affairs. While Liberal prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King* spoke sympathetically about Canadians’ struggles, his government’s interventions to counter the effects of the global depression were, Douglas argued, pathetically inadequate. He was frustrated that King was unwilling to do more to fix what Douglas considered to be a national emergency. In session after session he sought to save family farms by promoting legislation that would encourage land reclamation and water conservation, prop up grain prices, and prevent banks and municipal governments from repossessing land for non-payment of rent or back taxes. He had regular debates with former Saskatchewan premier James Garfield Gardiner*, King’s minister of agriculture.

Douglas was also frustrated by what he saw as Canada’s lack of action in addressing the worsening global situation in the late 1930s. He believed that a more activist position should be adopted against the aggression of dictators such as Italy’s Benito Mussolini and Germany’s Adolf Hitler. In 1936 Douglas went to Geneva to attend the World Youth Congress delegation meetings there, and while overseas he also visited Nazi Germany and then Spain, which was in the throes of a civil war [see Niilo Makela*]. Seeing German bombers in Spain, where Hitler was helping Francisco Franco’s fascist rebels to overthrow the country’s left-wing republican government, convinced Douglas that Nazi Germany was using the conflict there as a dress rehearsal for attacks on other nations. Upon returning home, however, he was held in check by conflict within the CCF on foreign-policy matters, and especially by the pacifist position taken by the leader, J. S. Woodsworth. To avoid an open rupture within the party, Douglas focused in parliament on urging the government to prevent Canadian companies from selling armaments and other materiel to the belligerent European dictatorships as well as imperial Japan.

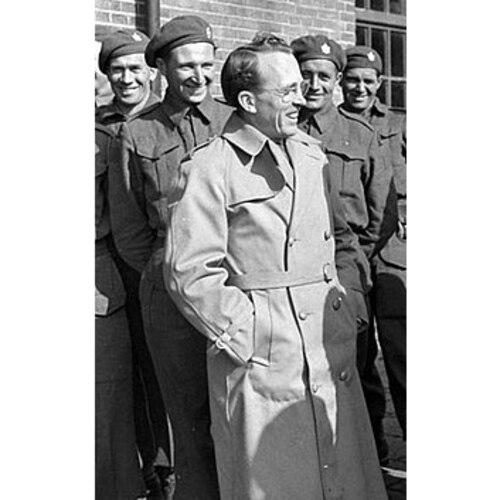

Like many socialists, Douglas abhorred war and believed that capitalists often used it to advance their interests. Yet he recognized that Hitler and Mussolini posed a grave threat to European democracies – including the United Kingdom – and after Germany invaded Poland on 1 Sept. 1939, he called for Canada to get ready to fight. Pacifists within his party were upset, and the prominent CCF academic Carlyle Albert King accused him of being “practically an imperialist.” After Canada declared war against Germany on 10 September, Douglas enlisted as a corporal with the 2nd Battalion of the South Saskatchewan Regiment. He then volunteered for active service overseas with the Winnipeg Grenadiers but was rejected on account of his osteomyelitis. The men he would have joined in that unit were sent to defend Hong Kong [see Henry Duncan Graham Crerar*], which was invaded and seized by Japan in December 1941. Those Canadians who died fighting, including their commander, John Kelburne Lawson*, were arguably the lucky ones; the rest had to endure the horrors of being prisoners of war.

There was, therefore, a personal dimension to Douglas’s vocal criticism of the King government’s management of events leading up to the fall of Hong Kong. He pointedly asked why it had sent “ill-trained, unequipped men 5,000 miles to defend a major outpost of the British Empire.” When his comments were condemned as aiding and abetting the enemy, Douglas’s response was bitingly sarcastic: if there was “inefficiency and incompetence at Hong Kong,” there seemed “little point in keeping it from the Japanese. They know all about it.”

In July 1941, while still an mp, Douglas had been elected president of the Saskatchewan CCF. He had run at the request of Major James Coldwell* and other CCF insiders who were concerned about the state of the party, which then had only about 5,000 members, as well as about the suitability of its leader, George Hara Williams, who was on military service in Europe. Clarence Melvin Fines*, a Regina alderman and Douglas supporter, was chosen vice-president. In July 1942 Douglas won the leadership, defeating Williams (who was still overseas) and John Hewgill Brockelbank; Fines was elected president. At the next year’s convention Douglas and Fines retained their positions and Brockelbank became vice-president, having been nominated by Douglas.

Since Douglas was still an mp who had to spend long periods in Ottawa, Fines did much of the groundwork to invigorate the party base, create a platform, and build an organizational machine capable of winning the next provincial election. When parliament was not in session, Douglas travelled the province, giving speeches, throwing out one-liners, and telling amusing stories – generally at the expense of Saskatchewan’s Liberal government – to anyone who would listen. He used radio addresses to reach everyone else. His charisma and sunny disposition allowed him to gradually transform what had been a protest party far to the left of the establishment parties into an alternative that was ready to assume government. By April 1944, a month before he resigned his federal seat to concentrate on the leadership, he and his team had increased the party’s membership to 26,000.

Built on the work of numerous party committees, the CCF’s platform, CCF program for Saskatchewan, was published in late 1943 as a 20-page booklet. It focused on four subjects: protecting the rights of farmers to security of land and the rights of workers to organize unions; expanding the welfare state, including implementing “a complete system of socialized health services”; reforming the education system; and building the economy through planning and targeted public ownership. (To avoid causing anxiety, especially among land-holding farmers, the manifesto emphasized planning rather than state ownership.) Douglas explained the need for change in a folksy manner that everyone could quickly grasp. In a series of radio broadcasts that allowed him to bypass the newspapers, which were invariably hostile to his socialist message, Douglas made his case, including a lesson on “cream separator” economics, in January 1944:

Last week we discussed the fact that the present economic system would lead inevitably to another world-wide depression after the war. Tonight I want to suggest an alternative economic system to the one we have at present. I have often likened our present capitalist economy to a cream separator. The farmer pours in the milk – he is the primary producer without whom society would collapse. Then there is the worker – he turns the handle of the cream separator – and it doesn’t matter whether he is a coal miner, a railroader, or a storekeeper, it is his labour which makes our economy function. The farmer pours in the milk and the industrial worker turns the handle.

However, there is another person in the picture – he is the capitalist who owns the machine. And because he owns it the machine is run exclusively for his benefit – that is why it is called the “capitalist” system. Now the capitalist doesn’t put in any milk nor does he turn the handle. He merely sits on a little stool with the cream spout fixed firmly in his mouth while the farmer and the worker take turns on the skim milk spout. Of course you can stay alive on skim milk – you will not get very fat, but you will at least be able to live – providing the skim milk keeps on coming; but it doesn’t. Periodically the capitalist gets so full of cream that he has indigestion, so he shuts off the machine, which means that the skim milk stops too. When he feels that he can use some more cream, the capitalist starts up the machine again and for a little while he gets the cream and you get skim milk. That has been the story of capitalism ever since we became a nation – we have a period of prosperity during which he gets cream and you get skim milk – followed by a depression during which you don’t even get skim milk.

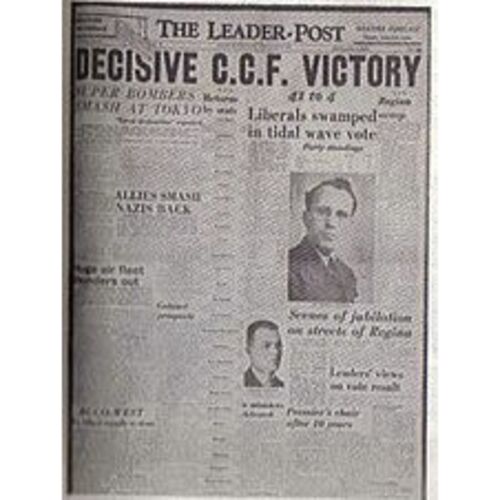

On 15 June 1944, election day in Saskatchewan, Douglas was confident of victory even though the Regina Leader-Post, loyal to Premier William John Patterson*’s Liberals, predicted that the incumbents would triumph. A Gallup poll had foreshadowed a CCF win, but the scale of the party’s victory came as a surprise to all. Douglas was at the CCF office in Weyburn listening to the radio when it was announced that 47 of the legislature’s 52 seats had gone to his party. It won 53 per cent of the popular vote, compared with 35 per cent for the Liberals and 11 per cent for the Progressive Conservatives. Douglas easily carried Weyburn, while Patterson nearly lost his riding to CCF candidate Gladys Strum. Clarence Fines later judged that the public had been so desirous of change that the CCF could have won a majority without Douglas, but “the enthusiasm generated by his leadership” caused the landslide. The results sent shock waves through the country. Under the youthful and optimistic Douglas – “a man of high ideals,” as King admitted in his diary – the avowedly socialist CCF had won its first victory, creating the impression that the party might gain power in other provinces and even threaten the Liberal hegemony in Ottawa.

Although jubilant at the results, Douglas immediately realized that with such a large majority he would have to manage huge expectations in his caucus and almost impossibly high expectations within the party. The new premier was in a hurry. He strongly felt that Canada had fallen behind the United Kingdom and the Nordic countries in creating a welfare state, and he wanted Saskatchewan to spearhead progressive change throughout the dominion. The province’s finances remained precarious after a decade of drought and depression, however, and Douglas knew that difficult choices among competing priorities had to be made.

Thanks to his enormous caucus, Douglas had the luxury of building a strong cabinet. First, he appointed Fines provincial treasurer. It was a challenging job: Fines had to simultaneously control expenditures efficiently, pay interest on the public debt that had been accumulated during the Great Depression, develop the provincial economy, and find the money to fund an array of ambitious new social programs. Also serving as deputy premier, Fines would become, according to senior civil servant Albert Wesley Johnson, the “master manager and financial wizard” of the CCF government, leaving Douglas time to take the lead on policy changes, especially in the health field. Other ministers were appointed to portfolios for which they had relevant experience or a natural affinity; former schoolteacher Woodrow Stanley Lloyd*, for example, became minister of education. With an average age of 46, the cabinet was a young one by the standards of the day, and Douglas, at 39, was one of the youngest political leaders in the country.

To implement his ambitious agenda, Douglas also needed a powerful and engaged civil service with greater administrative capacity than the one he inherited. He invited interested men and women to move to the province to work with his new government. The call was answered by Jewish Canadian socialists from Winnipeg’s North End (Meyer Brownstone and Mindel Sheps), brilliant Japanese Canadians who were being discriminated against throughout the country (Thomas Kunito Shoyama and George Tamaki), experienced New Deal administrators from the United States (Frederick Dodge Mott and Leonard Rosenfeld), and talented prairie idealists (Albert Johnson, Thomas Hector McLeod, and Donald Dougans Tansley). Affectionately known as the “Saskatchewan mafia,” these individuals would create what was arguably the strongest civil service in Canada. While many left after a few years, some, such as Shoyama, Johnson, and Tansley, stayed until the defeat of the CCF in 1964 and then became senior administrators in the federal governments of Lester Pearson and Pierre Trudeau, as well as the Liberal government of Louis-Joseph Robichaud* in New Brunswick.

Cabinet meetings led by Douglas, according to McLeod, “were a study in collegiality.” Ministers were expected to read the extensive material prepared by the cabinet secretariat. In true Westminster style, the premier sought to avoid polarizing votes, and meetings lasted as long as necessary to achieve what he felt was a workable consensus. He only stated his views after hearing out his ministers and often framed his position as a summary of the consensus itself. Douglas insisted that key groups and individuals were properly consulted on a proposed policy change, and that the analysis and options had been carefully vetted by his cabinet’s Treasury Board (and, from 1946 onwards, the Economic Advisory and Planning Board) before the cabinet made a final decision. He wanted to ensure that any decision met the highest possible political, fiscal, and technical standards. Afterwards, a report explaining the new policy was sent to both the caucus and a CCF advisory committee for review, and then for ratification by the CCF provincial council. Any major decision had to be ratified at the annual convention of the provincial CCF. In Douglas’s words, this process was “a very complicated set-up for arriving at decisions,” but it was also a small price to pay for the lubrication of one of the most effective political machines in the country.

Douglas developed a daily routine as premier that allowed him to endure the burdens of office. Getting up at 7:30 a.m., he had porridge, toast, orange juice, and coffee, and listened to the news on the radio. He then walked from his home to the Saskatchewan Legislative Building. He first dealt with the 100 to 300 letters per day that he received. After answering a few himself and supervising his secretaries’ replies to others, he forwarded the rest to the ministers with the relevant areas of responsibility. By 10:00 Douglas was either chairing cabinet meetings, which were held most days of the week, or meeting with his staff. Lunch was in the legislature’s cafeteria, where he sat down with civil servants and had a poached egg on toast and a dish of prunes, washed down with tomato juice, buttermilk, and a cup of tea. Appointments occupied most of Douglas’s afternoon, including meetings with delegations sent by some of the province’s hundreds of voluntary organizations. He tried to get home by 6:00 to have a light dinner, prepared by Irma in a way that would not irritate a long-standing stomach ulcer he had developed in earlier days when he did not eat regularly. Afterwards he often returned to the legislature for evening sittings or to his office to handle business missed during the day. He worked Saturday mornings but spent the afternoons with Irma and his two daughters. After church on Sunday, he caught up on his reading.

In its first few months in office Douglas’s government passed 76 bills, addressing issues ranging from farm debt to trade-union rights. Each new law made a change that Douglas had promised in the campaign or, in a few cases, that dealt with a pressing new issue identified by his cabinet. He realized that he was probably pushing the pace of reform dangerously hard – in a way that would tax both the human and fiscal capacity of his government and the patience of the electorate – but he greatly preferred an energetic approach to the danger of “going too slowly.”

Douglas encouraged his ministers and key deputy ministers to focus intensely on the economy. No province had suffered more during the Great Depression than Saskatchewan, whose economy had almost been destroyed. In his view, post-war reconstruction required diversification beyond agriculture to ensure that there could never be a return to the dangerous dependence on a single crop – wheat – that could again devastate the province if the world price fell. Douglas chose as his minister of natural resources Joseph Lee Phelps, who would become arguably the cabinet’s most independent member. His job was to figure out the best way of developing Saskatchewan’s rich storehouse of resources, including oil, natural gas, potash, and uranium, while managing the forests and fish stocks of the north. Unfortunately, Phelps made some rushed and ill-advised investments in a collection of small manufacturing enterprises that immediately lost money and earned the new government some bad publicity. Douglas realized he needed to exert more control over Phelps, and so he created a cabinet committee called the Economic Advisory and Planning Board. It was chaired, surprisingly, by an unelected civil servant, George Woodall Cadbury, a brilliant British socialist whom Douglas had recruited in 1946. Staffed by expert economists, including Thomas Shoyama, the board determined the pace and manner of development. With Douglas’s blessing, Cadbury and his team de-emphasized public ownership of resources in favour of private-sector ventures under government regulation. Utilities were another matter: the government soon owned and managed telephone, power, natural gas, and insurance enterprises.

Beyond public and private interests there were the cooperatives, a vibrant element in the Saskatchewan economy. Most of them had emerged in the interwar years as an alternative to for-profit corporations that were directed from central Canada. They ranged in size from the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool, with its hundreds of grain elevators spread throughout the province, to the tiny, locally owned and controlled credit unions that served just about every town. Douglas expected the co-ops to be at least as important in driving economic growth as the private sector and the crown corporations. He thus created the Department of Co-operation and Co-operative Development, which he would head from 1949 to 1960. During the CCF’s years in power, however, the relationship between his government and the cooperative movement would never fulfil his aspirations, and many co-op leaders and managers felt there were too many in Douglas’s circle, including Phelps, who preferred public to cooperative ownership.

The Douglas government actively encouraged cooperatives in northern Saskatchewan, where the majority of the population was indigenous. Fur- and fish-marketing co-ops were established so that Cree, Dene, and Métis residents could take greater control of their destinies. Douglas may have gone further than other premiers in his efforts to promote economic opportunities for indigenous peoples, but his policies and programs nonetheless reflected some of the colonial attitudes that were typical of the times.

Douglas’s personal priority was health care. In an unusual move, he had appointed himself minister of public health, a post he would retain until 1949. In keeping with his election promise that money would never be a barrier to seeking essential care, he immediately ensured that everyone on social assistance received free hospital, diagnostic, and physician services. Treatment for cancer and tuberculosis was also made free for all residents. He initially hoped that Ottawa and the provinces could agree on a national program of universal health care. His hopes were dashed when talks broke down at the Dominion–Provincial Conference on Reconstruction of 1945, but he remained determined to set up a provincial program. In this way, he intended to prove that such a policy was effective and thereby put public pressure on the federal government to come back to the negotiating table.

After a groundbreaking review of the provincial health system by renowned Johns Hopkins University professor Henry Ernest Sigerist in 1944, as well as internal staff work by a team of dedicated officials drawn from Canada and the United States, Douglas established universal hospital coverage on 1 Jan. 1947. The adoption of the Saskatchewan hospital plan, the first government-run single-payer scheme in North America, preceded the United Kingdom’s National Health Service by 18 months. The plan, which was funded by compulsory annual premiums of $5 per person (or up to $30 per family), turned out to be a great success, and expert delegations came from numerous jurisdictions to study its administrative structures.

When combined with all the other changes being wrought in the areas of human rights, labour law, social security, and education, the hospital plan taxed the capacity of the province in both human and fiscal terms. To many citizens the government’s agenda seemed like too much, too fast. Shortly after he retired from politics, Douglas reflected on this period of ferment. While admitting that the pace of change was likely excessive, he felt that he could neither have slowed the momentum the CCF had built up over its many years in opposition nor have disappointed the pent-up expectations of the party faithful. Nonetheless, he was convinced that the result of the 24 June 1948 provincial election, in which the party retained its majority but lost 16 seats, had been a message from the rest of the population to ease up. “Only a small minority might have their toes stepped on, but they tend to remember,” he recalled. “The many you have helped tend to forget.”

From 1948 until 1952 Douglas shifted his focus from social-policy reform to economic development, to consolidate the changes already made and ensure that his government would have the staying power to retain office for many more years. He explained the policy shift in the legislature, stating, “We have now gone as far as we can go in terms of social security until we put a better economic base under [it].” Phelps had been defeated in 1948, so Douglas replaced him by moving cabinet minister J. H. Brockelbank from municipal affairs to natural resources. His new department was responsible for identifying and mapping the areas where resources were likely to be found, and the private sector was left with the riskier job of prospecting for and then developing them. Douglas wanted the publicly owned Saskatchewan Power Corporation to distribute natural gas throughout the province, with charges equalized between urban and rural areas, despite the rural areas being more costly to service. Although the cabinet was reluctant to approve this policy because of the earlier failures of several of Phelps’s enterprises, Douglas convinced his colleagues that Saskatchewan Power would be an effective manager of this resource.

Progress was also made on health, although it was not as dramatic as it had been in the first term. The Douglas government expanded psychiatric services, built mental-health clinics, and improved the quality of leadership and staff in its psychiatric hospitals. Given his experience with the Weyburn mental hospital in the 1930s, Douglas was personally invested in bettering the lives of those suffering from mental illness. His government was among the most effective of all provincial administrations in using federal health grants to add to the number of hospitals and establish pilot projects for the innovative provision of community-level prevention and treatment services.

Douglas’s judgement on the need for consolidation was vindicated in election results: his government would increase its majority in 1952 and retain it in 1956, albeit with a decline in its share of seats and in the popular vote. During Douglas’s third and fourth terms the breathless excitement of the 1940s was replaced by policy incrementalism. The government honed its efficiency, building on a pattern of governance and public administration that would become admired throughout the country, and its economic strategy produced respectable growth, even though some private investors remained wary of putting money into the province. (Douglas believed that it was the corporate community’s general aversion to socialism, rather than the CCF’s tax policies, that kept these investors out.) Buoyed by the prosperous economy, the government ran a budget surplus every year, and Saskatchewan Power carried out a program of rural electrification that Douglas knew meant more to many residents than any other measure the CCF had implemented since coming to office.

While Douglas was immensely proud of the universal hospital plan enacted in 1947, he wanted much more. Eventually he hoped to cover all medically necessary expenses. The existing plan’s coverage of hospital care, diagnostics, and inpatient drugs was expensive, however, and any extension had to wait until the government had the money. The ensuing years of inaction tried the patience of both Douglas and the party faithful. Part of the problem was that Saskatchewan’s hospital plan, although popular, had not put as much public pressure on the federal government as Douglas had hoped. The Liberal government led by Louis-Stephen St-Laurent* felt no compulsion to act and preferred to avoid the issue. It was only after John George Diefenbaker*’s Progressive Conservatives formed a government in 1957 that federal cost sharing for the Saskatchewan program became a reality, kicking in on 1 July 1958. Douglas immediately started planning a major extension of coverage, one that would include physician services.

After a comprehensive internal study, Douglas’s officials concluded that it made sense to first extend universal coverage from hospitals to physician care. As fiscal resources permitted in the future, this coverage could be broadened to include prescription drugs, followed by home care, dental care, and other medical services. Douglas assumed that the new policy would evolve in much the same way that the hospital plan had. He did not fully appreciate that the political environment had changed, and he was facing a wall of opposition. In the 1950s the medical profession, influenced by doctors who had left Great Britain because of the National Health Service, had hardened its stand against what it increasingly termed “socialized medicine.” At the same time, the other nine provincial governments opposed medicare, as it was colloquially known, either on philosophical grounds or to avoid the fiscal burden it would impose.

Douglas wanted a single-payer insurance system for physician care in Saskatchewan, similar to the one that had been established for hospital treatment; all patients’ bills would be automatically paid by the state. The province’s doctors, however, insisted on a multi-payer approach, in which the government would subsidize the purchase of private insurance by the very poor. Medicare was the dominating issue of the Saskatchewan election of 8 June 1960. In contrast to its past practice, organized medicine became a direct participant. The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Saskatchewan fought the CCF through an aggressive and expensive publicity campaign that was supported by the Canadian Medical Association and the American Medical Association, neither of which wanted a beachhead established in North America for single-payer medicare. The CCF nevertheless won its fifth majority government, taking 37 of 54 seats (albeit with a four per cent drop in its share of the popular vote), and Douglas felt he had been given a clear mandate to implement medicare on his terms. His political position in Saskatchewan, however, had become complicated by the fact that the CCF’s federal executive had quietly started promoting the idea that he should leave the premiership for a leadership role on the national stage.

The federal CCF had captured 25 ridings in 1957, but in the general election of 31 March 1958 it won only eight seats and its leader, M. J. Coldwell, was personally defeated. After that disastrous performance, work began on the establishment of a new party. Although Douglas was unable to devote much time to federal politics, his status as the only CCF premier gave him considerable influence in the national party’s affairs. For example, he had been directly involved in replacing the 1933 Regina Manifesto with the less stridently socialist Winnipeg Declaration of Principles that was passed by the CCF convention of August 1956.

The goal of the CCF’s national executive, led by lawyer David Lewis and Douglas’s old colleague Stanley Knowles, was to refashion the party so that it would gain the organizational backing of labour unions across the country. Douglas supported the principle behind what was then known as the New Party because, as he told the Toronto Daily Star on 17 Nov. 1958, he saw it as “a vehicle in which all left of centre groups and individuals can ride.” He wanted the New Party to be explicitly reformist, with a focus on improving and extending the welfare state, building an economy that would deliver greater opportunities for secure employment, and giving working-class Canadians more democratic control over the future direction of the country. He believed that Canada was destined to return to a two-party system, with the Progressive Conservatives absorbing centre-right Liberals and the New Party becoming the home for Liberals with social democratic values. On 22 Feb. 1961 he explained his thinking in a letter to the mayor of Winnipeg:

This is precisely why some of us feel the need for a New Party. The conditions which produced doctrinaire socialism no longer exist. Whether we like it or not, we are steadily moving into a welfare state and most of the planning techniques have been built into our economy. Keynes has proved to be more potent than Marx and our society has all the tools it needs to promote full employment and a high standard of living without the rigid restrictions that were envisaged thirty years ago.

However, Douglas expressed serious misgivings about the way in which the national executive and organized labour were managing the establishment of what would come to be called the New Democratic Party (NDP). He wanted the CCF’s constituency and provincial associations to be more involved so that the NDP would not look like a fait accompli by the New Party executive and the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC), the country’s largest union organization. Douglas could feel the antipathy towards “Big Labour,” particularly among the farmers who had been instrumental in creating the CCF. He thought that the farmers and their organizations should be an essential part of the NDP, and he urged the CCF’s national executive to take the extra time to bring them in, “even if it means setting up some special organization such as a farmers’ committee for political action.” In his view the “proposed alignment” would not gel until considerably more work was done “at the grass roots level.”

By the following spring, just as Douglas was distancing the Saskatchewan CCF from the New Party, the campaign to recruit him for federal politics was fully underway. In response to a March 1960 request from the federal CCF caucus, Douglas had written that he was “appreciative” of the offer, but it was “out of the question,” since his “first duty” was to stay in Saskatchewan and “carry out the program,” in particular medicare. His resolve wavered only when it became clear that Hazen Robert Argue*, a CCF mp from Saskatchewan, would contest the leadership. Argue succeeded Coldwell as CCF leader in August 1960 and thereby placed himself in an advantageous position to seek the leadership of the New Party. The stakes were raised when Lewis, Knowles, and Claude Jodoin*, founding president of the CLC, publicly pledged their support to Douglas in early 1961.

Privately, Douglas tried to persuade Lewis to run, but Lewis and the other CCF executive members concluded that he would be considered labour’s candidate and Argue the farmers’ candidate, and the election of either man would divide the party. Argue, in particular, was perceived by the executive members to be unsuitable for the position: he was too much of a careerist and not enough of a social democrat. (Also, Lewis felt that he harboured anti-Quebec views.) Only Douglas seemed capable of uniting the two factions. Even more important to some, he alone had the leadership experience and charisma to bring on board the “undecided and doubtful.” In April 1961 Douglas finally agreed to run, but only if he received overwhelming support from the CCF constituency associations and from his caucus and cabinet. Even after the letters of support rolled in, he did not announce his decision to seek the leadership until June. He then refused to campaign, remarking that it was better “the position should seek the man than the man seek the position.” This statement infuriated Argue, who had been actively campaigning.

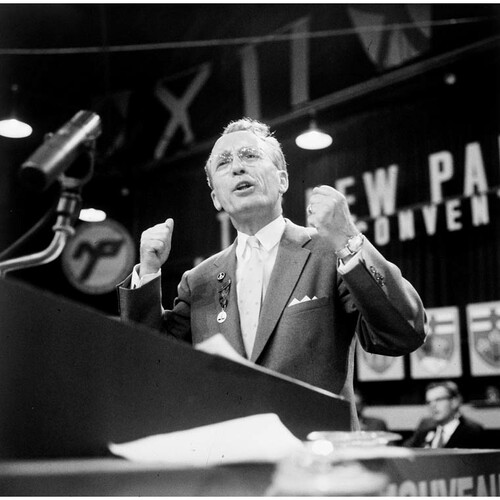

The founding convention of the NDP, held in Ottawa in early August 1961, produced an outward show of unity and considerable publicity for the party. The leadership election was a resounding triumph for Douglas, who received 1,391 votes to Argue’s 380. His victory speech started in French with a plea for national unity and ended in soaring English with a slightly amended version of lines written by English poet William Blake. Its words captured Douglas’s burning desire to create a better future for all Canadians: “I shall not cease from mental fight / Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand / Till we have built Jerusalem / In this green and pleasant land.”

Before he could take over the NDP full-time, Douglas needed to return to Saskatchewan, where a storm was brewing over medicare. At first he had believed some compromise with the medical profession might be possible, and in April 1960 he had established a commission on medicare, headed by former University of Saskatchewan president Dr Walter Palmer Thompson, that eventually included three doctors representing the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Saskatchewan. They had filibustered the Thompson Committee, as it became known, to the point that it barely functioned. After more than a year of costly delays Douglas forced the committee to deliver an interim report, which was issued in September 1961. The majority of its members supported universal coverage on the terms that the government had originally envisaged, while the three doctors and the lone representative of the business community issued a dissenting report that rejected single-payer medicare in favour of government subsidies for citizens who could not afford private insurance.

Undaunted, Douglas presented the medicare bill to the house in October and then led the debate on second reading in the legislature. To opposition criticisms of the cost of the program, the premier responded:

It seems to me to be begging the question to be talking about whether or not the people of this province, or the people of Canada can afford a plan to spread the cost of sickness over the entire population. This is not a new principle. This has existed in nearly all the countries of western Europe – many of them for a quarter of a century.… When we’re talking about medical care we’re talking about our sense of values. Do we think human life is important? Do we think that the best medical care which is available is something to which people are entitled, by virtue of belonging to a civilized community?

After the debate Douglas departed the premier’s office for his new job as leader of the national NDP. He was succeeded as premier by Woodrow Lloyd, who faced the hard task of bringing the medicare program into existence in spite of the fierce opposition of doctors.

With Douglas as leader, many within the party expected that the NDP could become the official opposition, if not the government itself. Douglas knew better. He believed it would take at least a quarter of a century before the NDP could gain enough support – beyond what it already had from farmers and workers – to form a government. It needed time to sink roots in central and eastern Canada, where it was viewed as a western protest party. The NDP, however, had little money and limited organizational capacity. When Diefenbaker called an election for 18 June 1962, Douglas chose to run in Regina City, in part because there was an airport there and he was expected to campaign across the country.

From the beginning Douglas had two strikes against him. First, Diefenbaker and the Progressive Conservatives remained highly popular in Saskatchewan, even though their support was fading in the rest of the country. Secondly, the intense battle over medicare was polarizing the population of Saskatchewan in a way that no issue ever had. The anti-medicare forces accused Douglas of having rushed the program through so that he could use it to improve his standing in national politics. In the weeks leading up to the federal election, Saskatchewan’s doctors had made it clear that they would be going on a provincewide strike to prevent the implementation of medicare, which was scheduled for 1 July. Although Lloyd had taken over the premiership, Douglas was still identified – both by allies and by enemies – as chiefly responsible for medicare.

On election night he suffered the most humiliating defeat of his life. Despite having spent 16 years as premier in the capital, Douglas received less than 29 per cent of the vote in Regina City. To punish him for medicare and ensure his defeat, many local Liberals had voted for his Progressive Conservative adversary, who was elected with more than 50 per cent support. Nationally, the NDP managed to get 19 members elected, a major improvement on the CCF’s performance in 1958 but far below the expectations of those who had established the New Party. Most disappointing of all, a poll soon showed that much of the labour vote had gone to the Liberals. Douglas was shocked at the margin of the loss, but his resilience and instincts as a boxer came to the fore in his concession speech, when he quoted from a Scottish border ballad: “Fight on, my men, said Sir Andrew Barton, / I am hurt, but I am not slain. / I will lay me down and bleed awhile, / And then I’ll rise and fight again.”

Douglas could take consolation in two events that occurred soon after the election of 1962. First, Woodrow Lloyd and the Saskatchewan CCF succeeded in implementing medicare, outlasting a 23-day doctors’ strike. Secondly, the NDP mp for Burnaby-Coquitlam, in British Columbia’s lower mainland, resigned on his own initiative so that Douglas could run in the subsequent by-election. He did so, won the seat, and then carried on the business of leading the NDP. However, things did not return to normal. Douglas’s image as a confident winner had been permanently damaged in the eyes of some in the party and many in the general electorate. A whispering campaign began: he did not look modern enough for the role; his French was poor; he was better on radio than television; his folksy speeches harked back to a bygone era. Some of these criticisms were more widely expressed after the NDP went down to 17 seats in the election of 8 April 1963, which saw Lester Pearson’s Liberals win a minority government. The NDP would improve slightly on 8 Nov. 1965, with a 21-seat showing and an increase of 4.7 per cent in the popular vote.

As the NDP looked to the federal election of 1968, some worried that Douglas seemed worn in comparison to Pierre Trudeau, the new Liberal prime minister. A young Ontario NDP member, Stephen Henry Lewis (son of David Lewis), had already approached Douglas and tried to convince him that it would be best for the party if he retired. Douglas privately told the party that he would fight the 1968 election and then step down as leader at the 1969 NDP convention. Despite the fact that “Trudeaumania” carried the Liberals to a majority government on 25 June, the NDP held its own, taking 22 seats even as it dropped a point in the popular vote. However, Douglas lost his newly redrawn riding of Burnaby-Seymour, and his retirement was delayed while he sought a new seat. In February 1969 he impressively won the by-election in the British Columbia riding of Nanaimo-Cowichan-The Islands. Afterwards he and the party executives started planning for an orderly transition of the leadership; he would ultimately stay on until 1971.

There is more to opposition than electoral results, of course, and in many respects Douglas excelled. He punched far above his weight in terms of pushing the agenda of the Pearson and Trudeau governments to the left. Since Pearson had a minority government, Douglas was able to use the NDP’s leverage to help bring about the Canada Pension Plan and to urge Pearson’s divided cabinet to support a strong form of universality for medicare in the Medical Care Act of 1966. When the Liberals pushed the program’s start date from 1 July 1967 to 1 July 1968, Douglas criticized the decision and kept up the pressure to ensure there were no further delays. Liberal policies were also influenced by former members of the Saskatchewan mafia who had become senior officials in the Pearson and Trudeau governments. Albert Johnson, for example, played an important role in the establishment of national medicare, the redesign of social security, and the expansion of post-secondary education through federal transfer funding.

The 1960s were a decade of momentous social and political changes. Anti-colonialism swept the world, and Douglas was an ardent champion of what he viewed as liberation movements that were struggling for self-government against imperial powers. Vehemently opposed to what was, in his opinion, the federal government’s complicit support for the United States in the Vietnam War, he sympathized with the Vietnamese in their centuries-old struggle against the colonialism of China, France, and then, as he saw it, the United States. He argued for international resolution of the conflict, and maintained that the great powers should stop using Vietnam as a surrogate for their own objectives and instead “arrange a peace on the basis of a guarantee” of that country’s “territorial neutrality.” By 1967 his elder daughter Shirley, an actor, had moved to Hollywood with her actor husband, Donald McNichol Sutherland. They too were outspoken opponents of the war. Shirley also backed the African American political movement known as the Black Panthers. Two years later, when she was charged with conspiracy to possess unregistered explosives, Douglas immediately went to Los Angeles to support her. At a press conference he stated, “I am proud of the fact that my daughter believes, as I do, that hungry children should be fed whether they are Black Panthers or white Republicans.” For her part Shirley argued that the Panthers’ political program was very similar to that of the NDP, and that the Panthers simply “wanted the right to bear arms to defend their homes.” She was acquitted of the charge.

Douglas’s anti-war activities in the 1960s were carefully monitored by the security branch of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) on behalf of the federal government. This surveillance had a long history: beginning in 2006 newly declassified RCMP files would reveal that Douglas had been spied on from the late 1930s to the 1980s. The force’s primary mission was to discover whether he had ties to the Communist Party of Canada (CPC). A 1980 internal assessment of the dossier states: “Douglas has been known personally by and has associated with leftists, peace movement workers and C. P. of C. members for years. He has allowed his name to stand publicly on many occasions in relation to support of issues sponsored by leftist groups.” While admitting that “it is difficult to determine the full depth of sympathy and involvement or influence, if any, these groups or their philosophies have over him,” the assessment nevertheless concludes, “there is much we do not know about Douglas and the file should be maintained in order to correlate any additional information that surfaces which might assist in piecing this jigsaw puzzle together.” In fact the relationship between the CCF–NDP and the CPC was always fraught with tension. Douglas did speak at events attended by communists because he believed that all citizens possessed the rights of free speech and peaceful protest. But he worried that any perceived communist infiltration of his party would allow its opponents to misleadingly associate it with the totalitarian regimes in eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, and China. By the same token, many communists in Canada saw the democratic and non-revolutionary CCF–NDP, in the words of a senior communist official, as “one of the greatest hindrances to the establishment of socialism in Canada.”

During the late 1960s the Front de Libération du Québec (FLQ) used violence, including bombing the Montreal Stock Exchange in 1969, in an attempt to secure the province’s independence from the rest of Canada. In October 1970 the FLQ kidnapped a British diplomat, James Richard Cross, and then Quebec’s minister of labour, Pierre Laporte*. After the Trudeau government invoked the War Measures Act, suspending civil liberties and giving the police greater powers to arrest suspects, the FLQ murdered Laporte. Douglas joined the Liberals and Progressive Conservatives in condemning the killing, but he became the most vocal critic of Trudeau’s tactics, arguing, “The government, I submit, is using a sledgehammer to crack a peanut.”

His opposition drew a storm of popular protest, because the vast majority of Canadians inside and outside Quebec backed Trudeau’s hard line against the FLQ through the War Measures Act. There were even pockets of strong support for this action within the NDP, and in his own riding Douglas faced the wrath of many previously loyal followers. Only years later, with hindsight and a reappraisal of the use of the act, would Douglas’s controversial position be validated on both human-rights and political grounds. In 2012 one of Trudeau’s cabinet members during the crisis, Eric William Kierans*, recalled: “It was Tommy Douglas of the NDP who stood in the House, day after day, and hammered the government for suspending civil liberties, and if you ask me today why I wasn’t up there beside him I can only say, damned if I know. He showed political courage of the highest order.”

At the NDP convention held in Ottawa in April 1971, Douglas was succeeded by David Lewis, the man he felt should have become leader a decade earlier. Douglas’s convention speech enumerated the party’s achievements during his tenure, highlighting the pressure his caucus had placed on the Pearson and Trudeau governments to act on pensions, health care, housing, and the environment. Since its founding, the NDP had doubled the CCF’s level of popular support and had tripled its representation in the House of Commons. Nonetheless, being a third-party opposition leader and critic must have felt less rewarding to Douglas than leading a government and making changes.

Although Douglas would remain in the House of Commons, he was careful not to interfere with Lewis’s leadership. In 1972, for example, he did not speak out when Lewis ejected the Waffle (the NDP’s left-wing, nationalist rump) from the party, even though Douglas had been relatively open to its ideas and tactics during his years as leader. At the same time, he became chair of the newly established Douglas-Coldwell Foundation, named for himself and his old CCF ally M. J. Coldwell. Its purpose, as Douglas put it, was to “make it possible for those with radically different ideas about democratic socialism to submit them to consideration without fear of being labelled either heretics, or having any political party accept responsibility for the ideas which they are advancing.” Douglas did take sides on some issues, however. He spoke in favour of Lewis’s support for Trudeau’s oil and gas tax policies, which were opposed by Saskatchewan NDP premier Allan Emrys Blakeney*. And in 1975, Douglas backed John Edward Broadbent for the party leadership and was honorary chair of his campaign. Given Douglas’s position as the NDP’s éminence grise, his endorsement of Broadbent dismayed the other candidates and was questioned by some in the party.

When Tommy gave up his seat in the House of Commons in 1979, after having spent four and a half decades in public life, he was 74 years of age. Following his retirement he set up shop in the capital at the Douglas-Coldwell Foundation, and he continued to speak at various events. He also had time to enjoy leisurely lunches at a favourite restaurant on Metcalfe Street, near his foundation. To the surprise of some of his past supporters, he joined the board of directors of Husky Oil, in part because it was one of the few Canadian companies in a sector dominated by American multinationals.

Douglas was finally able to set aside time for personal interests. He and Irma bought a summer cottage on the Gatineau River near Wakefield, Que., where they were often joined by their grandchildren. They also enjoyed six-week vacations to Florida to escape the Canadian winter. It was a warm and wonderful period, but it ended quickly.

In mid 1981 Douglas discovered that he had incurable cancer. By the time he attended the NDP convention in Regina in July 1983 the disease had made him gaunt, but his speech was one of the most visionary of his life. He received a thundering standing ovation that seemed to never end – an extended thank you from the party he had served for so long.

On 24 Feb. 1986 Tommy Douglas died of cancer at his home in Ottawa. Leaders of all political parties attended his funeral service. The eulogist, long-time NDP activist John King Gordon, described him “as a man of integrity” and praised his “clarity of thought” and “commitment to values.” In a dry, deadpan tone, Gordon then noted Douglas’s “appreciation of the dialectical relationship between truth and absurdity which we call humour.” Douglas was honoured with a standing ovation led by Prime Minister Martin Brian Mulroney and Liberal leader John Napier Turner*. He was buried in Ottawa’s Beechwood Cemetery, alongside many others who had devoted their lives to serving their country. The originator of medicare was gone, but a generation later he would be remembered as the country’s greatest Canadian.

Most of the primary material on Thomas Clement Douglas’s political life is divided between the Provincial Arch. of Sask. (PAS) in Regina and Library and Arch. Can. (LAC) in Ottawa, pursuant to an agreement reached by Douglas and the two archives. The T. C. Douglas fonds at PAS (F 117) covers his years as premier of Saskatchewan, and the Tommy Douglas fonds at LAC (R3319-0-1) contains information about his career in parliament and his leadership of the New Democratic Party. Digitized primary documents relating to Douglas, the Saskatchewan Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), and the 1944 provincial election can be consulted on the PAS website at www.saskarchives.com/CCF_in_Saskatchewan.

Although he never wrote memoirs, in 1958 Douglas gave a series of interviews to journalist C. H. Higginbotham that was later edited by L. H. Thomas in The making of a socialist: the recollections of T. C. Douglas (Edmonton, 1982); this work comes closest to resembling an autobiography. In 1981 and 1982 Douglas was interviewed by Jean Larmour for an oral history of the Saskatchewan CCF government; thousands of pages of transcripts from this project are available at PAS, R-1214 (Larmour, Jean file). Some of Douglas’s speeches have been reproduced in Tommy Douglas speaks: till power is brought to pooling, ed. L. D. Lovick (Lantzville, B.C., 1979). Reflections on Douglas’s life, in some cases by individuals who worked extensively with him in politics and government, can be found in Ed Whelan and Pemrose Whelan, Touched by Tommy: stories of hope and humour in the words of men and women whose lives Tommy Douglas touched (Regina, 1990).

There are many biographies, but they are highly repetitive in content and, for the most part, similarly hagiographic in tone. The best of the lot is Tommy Douglas: the road to Jerusalem (Edmonton, 1987) by T. H. McLeod and his son Ian McLeod. The senior McLeod, who was one of Douglas’s closest advisers in Saskatchewan, draws upon a diverse array of sources to generate what remains the most thoroughly researched and comprehensive biography of the man as a preacher and politician. The McLeods prepared a very succinct version of this book for their chapter on Douglas in Saskatchewan premiers of the twentieth century, ed. G. L. Barnhart (Regina, 2004). The second-best biography, and likely the most widely read, is D. F. Shackleton, Tommy Douglas (Toronto, 1975). Robert Tyre, a journalist who opposed Douglas’s political philosophy and his CCF government, wrote the earliest and most critical biography, Douglas in Saskatchewan: the story of a socialist experiment (Vancouver, 1962), during the crisis over the implementation of medicare in the province.

Since the 1990s a number of other biographies have appeared, including Dave Margoshes, Tommy Douglas: building the new society (Toronto, 1999); Walter Stewart, The life and political times of Tommy Douglas (Toronto, 2003); and Vincent Lam, Tommy Douglas (Toronto, 2011). However, very little new information has been added by these authors. The only scholarly examination of Douglas’s government is A. W. Johnson with Rosemary Proctor, Dream no little dreams: a biography of the Douglas government of Saskatchewan, 1944–1961 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 2004). This book, which provides considerable insight into Douglas himself, is the most important account of how he organized his government, cabinet, and bureaucracy to implement the most ambitious post-war reform agenda achieved by any government in Canada. There is much useful material on the Saskatchewan CCF government in John Richards and Larry Pratt, Prairie capitalism: power and influence in the new west (Toronto, 1979). A 1948 reprint of the booklet describing the CCF’s platform for the 1944 election can be found at peel.library.ualberta.ca/bibliography/7005.html.

Additional information can be gleaned from biographies of Douglas’s contemporaries, including Dianne Lloyd, Woodrow: a biography of W. S. Lloyd (n.p., 1979); Susan Mann Trofimenkoff, Stanley Knowles: the man from Winnipeg North Centre (Saskatoon, 1982); and Norman Ward and D. [E.] Smith, Jimmy Gardiner: relentless Liberal (Toronto and Buffalo, 1990). The legendary parliamentary debates between Douglas and Gardiner in the late 1930s and early 1940s can be accessed at Library of Parliament, “Canadian parliamentary historical resources”: parl.canadiana.ca (consulted 23 Jan. 2020). Their historic rivalry was depicted in the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s two-part television miniseries, Prairie giant: the Tommy Douglas story (video, n.p., 2006; available at youtu.be/OgIhMczSYV0). The show received criticism for its historical inaccuracies, and after Gardiner’s granddaughter and others complained that his portrayal was unfair and erroneous, the CBC stopped broadcasting the series and sold it to foreign distributors.

Cite This Article

Gregory P. Marchildon, “DOUGLAS, THOMAS CLEMENT (known as Tommy Douglas),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 21, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 23, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/douglas_thomas_clement_21E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/douglas_thomas_clement_21E.html |

| Author of Article: | Gregory P. Marchildon |

| Title of Article: | DOUGLAS, THOMAS CLEMENT (known as Tommy Douglas) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 21 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2021 |

| Access Date: | January 23, 2025 |