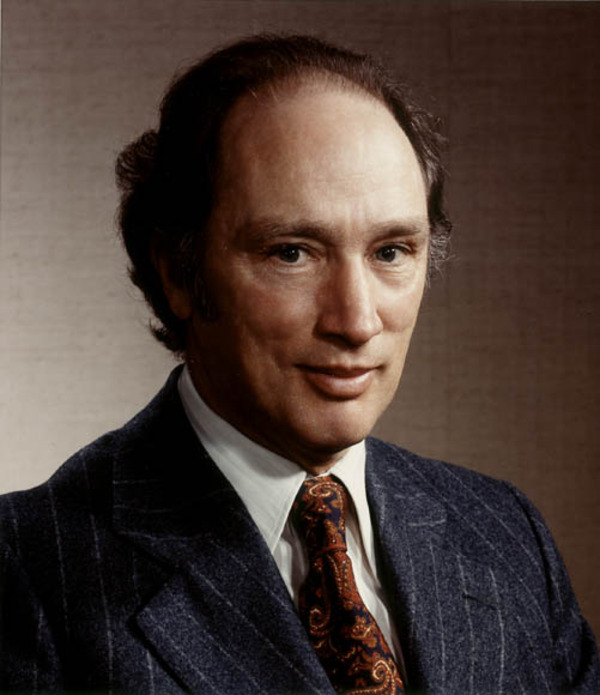

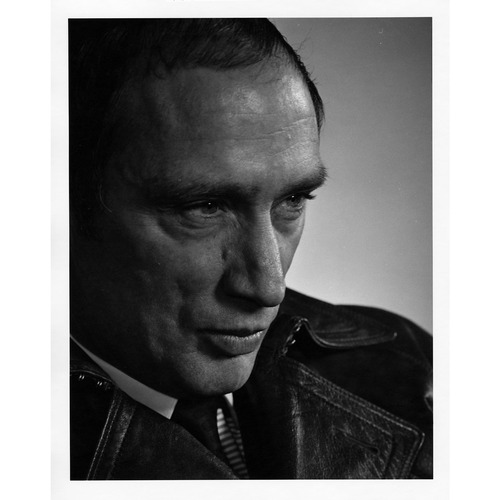

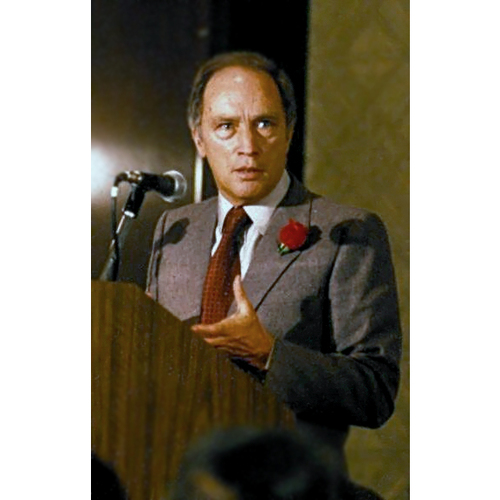

TRUDEAU, PIERRE ELLIOTT (baptized Joseph-Philippe-Pierre-Yves-Elliott), lawyer, author, university professor, and politician; b. 18 Oct. 1919 in Outremont (Montreal), son of Joseph-Charles-Émile Trudeau* and Grace Elliott; m. 4 March 1971 Margaret Sinclair in Vancouver, and they had three sons; they divorced in 1984; he also had a daughter with Deborah Coyne; d. 28 Sept. 2000 in Montreal and was buried in Saint-Rémi, near Napierville, Que.

On his father’s side, Pierre Trudeau (he would add Elliott in the 1930s and sometimes used a hyphen) was a descendant of Étienne Truteau (Trudeau), a carpenter from La Rochelle, France, who had arrived in New France in 1659. Pierre’s father, known to his friends as Charlie or Charley, was born on a farm in Saint-Michel, south of Montreal. Although Charlie’s father, Joseph, was semi-literate, his mother, Malvina Cardinal, was a mayor’s daughter who insisted that their sons be given a good education. Charlie became a lawyer and practised in the heart of Montreal’s business district.

Grace Elliott, Trudeau’s mother, came from a prosperous Montreal family. Her father, Phillip Armstrong Elliott, an Anglican of loyalist stock, had married Sarah-Rebecca Sauvé, a French Canadian Roman Catholic, and, as was required by the Catholic church for children of interfaith marriages, Grace was raised as a Catholic. Phillip Elliott’s wealth came from real estate investments in Montreal. In 1903 he removed Grace from her convent school there and placed her in the Dunham Ladies’ College, an Anglican women’s finishing school in the Eastern Townships. Although she spoke and wrote French, she preferred English, which would be the language of the Trudeau home.

Charlie and Grace married in 1915 and they soon had children, first Suzette in 1918 and then Pierre in 1919. Another child, Charles, whom the family would call Tip, followed in 1922. By this time, Charlie had largely abandoned his commercial law practice in favour of a business career. Success had come with his creation in 1921 of the Automobile Owners’ Association, which comprised two Montreal gas and service stations and offered a program whereby car owners paid a yearly fee for guaranteed service. It was a brilliant device. The number of automobiles in Quebec swelled from 41,562 in 1920 to 97,418 in 1925 and would almost double again by 1930, when it reached 178,548. At the end of the 1920s the family moved from a modest row house in Outremont to a much larger but unpretentious dwelling there that could accommodate not only the Trudeaus but also a maid and a chauffeur. Although he would have apartments elsewhere, Pierre would consider it his home until he moved into the prime minister’s residence at 24 Sussex Drive in 1968.

In the Great Depression of the 1930s Charlie Trudeau became wealthier and his automobile business, with some 30 service stations, was sold in 1932 to a subsidiary of the Imperial Oil Company for approximately $1,000,000, which he quickly invested. An ebullient, rough-edged businessman, he often gambled long into the night. There is evidence of hard living, including records of his large losses and wins, as well as family memories of his frequent absences. Yet he was a doting and demanding father who deeply impressed Pierre and they exchanged extremely affectionate letters. Subsequent rumours that Charlie abused Grace when he returned late at night are almost certainly false, although there is no doubt that the polished graduate of Dunham found her husband’s antics difficult. They took their toll on Charlie as well. In the spring of 1935 he had a heart attack and died at age 46. His death deeply affected Pierre, who concluded, probably correctly, that it was the result of the social demands of the business world. Pierre became resistant to these practices and an ascetic in many of his own tastes. He did not gamble, disdained smoking, drank very little, and avoided wild parties. Such aloofness was made easier by the considerable fortune he had inherited, which gave him a freedom enjoyed by few others of his generation.

Charlie Trudeau’s influence on his son was indelible; in assessing it, one must not conclude that his English-speaking home and association with the largely anglophone Montreal business class reflected his political views and private beliefs. Although Pierre had begun classes in English at the bilingual Académie Querbes in Outremont, he was quickly shifted to its French classes as soon as his English became fluent. In 1932 his father enrolled him in the Jesuits’ new Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf, already the favoured school of the francophone elite and a centre for Catholic and youthful nationalist debate and thought in the 1930s. Charlie was a nationalist, supportive of the Catholic Church, the French language, and Quebec’s place within the Canadian confederation. In politics he was a Conservative who was also a financial adviser of Le Devoir (Montréal), the principal voice of nationalism among Quebec newspapers. He was close to Camillien Houde*, the mayor of Montreal and the former leader of the provincial Conservative Party.

Pierre Trudeau’s pride in his father, which he never lost, derived in large part from his admiration of Charlie’s success in business, a field from which francophones were largely absent in the early 20th century. He appears to have seldom discussed politics with his father, but Brébeuf was alive with political debate. Trudeau was introduced to nationalist thought and took part in rallies against perceived threats to the church and the French Canadian people. In a play he wrote in 1938, performed at Brébeuf, he satirized the tendency of his compatriots to patronize Jewish merchants and, implicitly, supported the Achat Chez Nous movement. An outstanding student, he reflected the milieu in which he thrived, one that was increasingly nationalist, supportive of corporatism, critical of capitalism and democracy, and wary of British and Canadian foreign policy as it moved hesitatingly forward on the road to war. Yet Trudeau could be a contrarian, cheering the victory of Major-General James Wolfe* over Louis-Joseph de Montcalm*, Marquis de Montcalm, in class and challenging what he termed exalted patriots, those students who attacked bilingualism and mixed marriages. After he learned that another student thought he was “Americanized, Anglicized,” he wrote in his diary that he was proud of “my English blood which comes from my mother.”

After his father’s death, Trudeau turned to his mother, who became the predominant figure in his adolescent life. He doted on her and she on him. His exceptional academic record pleased her greatly and she granted him the freedom that a favoured child so often obtains. With no financial concerns, he travelled frequently to New York, spent summers at Old Orchard Beach in Maine, took long canoe trips through the Canadian Shield, wildly drove a Harley-Davidson motorcycle, and bought books, records, and concert tickets few of his classmates could afford. In his final year at the college, 1939–40, he edited the school newspaper, Brébeuf, in which he challenged the college administration, and finished first.

Brébeuf remained largely silent during the first months of World War II. Few students enlisted and indifference was the prevailing mood. Attitudes changed quickly, however, when France fell in June 1940 and the government of Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King passed the National Resources Mobilization Act, introducing conscription for home defence. Earlier, Trudeau had casually suggested to his American girlfriend, Camille Corriveau, that he might enlist for the sake of adventure. Now he took up the call of Mayor Houde and others who denounced conscription and urged French Canadians to defy mandatory registration for military service. Resentfully, he entered the compulsory Canadian Officers’ Training Corps, which required regular drill and more extensive summer training. He began studies in law at the Université de Montréal in the fall and immediately attended lectures on Canadian history by the nationalist Abbé Lionel Groulx*, but two other priests were far more influential in shaping his thoughts and actions at this time.

Trudeau had met Marie-Joseph d’Anjou and Rodolphe Dubé* at Brébeuf. Father d’Anjou was one of his favourite teachers. Father Dubé was renowned not only for his teaching but also for his writings, published under his nom de plume, François Hertel. He became influential in debates about faith, politics, and Quebec’s destiny, especially among the young. Charismatic, brilliant, and often outrageous, Hertel increasingly drew Pierre and his brother Charles into his circle. In the case of Pierre, he became a confidant, a confessor, and an inspiration in the early 1940s, even though his superiors moved him to Sudbury, Ont., because of his unorthodox approaches to religious teaching. Trudeau wrote to him regularly and visited him in Sudbury. An advocate of personalism, Hertel encouraged Trudeau to read philosophers Jacques Maritain and Emmanuel Mounier and the devout but rebellious young Catholic found their approach to personal liberty emancipating, although he also found corporatist thought and the conservative nationalism of Charles Maurras compelling. Personalism has many interpretations, but for Trudeau it meant that “the person ... is the individual enriched with a social conscience, integrated into the life of the communities around him and the economic context of his time, both of which must in turn give persons the means to exercise their freedom of choice.” Refined by later studies, this personalism formed the core of Trudeau’s religious understanding of the relationship between the individual and society. That full understanding, however, would come slowly.

Hertel’s unorthodoxy intrigued the young Trudeau as he sought answers to the question of identity. His anger mounting, Trudeau followed Hertel’s counsel to become active in the struggle against conscription and to become revolutionary. He participated in the Frères-Chasseurs, who planned to rise up against the oppressors in Ottawa. Adopting a revolutionary pose, he signed his letters to Hertel “citoyen,” took part in street riots, and worked in a secret society, the LX, with his friends François-Joseph Lessard, Jean-Baptiste Boulanger, and others to overthrow what they considered a corrupt system. Hertel placed the revolution within the anti-bourgeois and anti-democratic traditions in Catholic thought. He and Trudeau debated how the latter should be involved; radical approaches ranging from the anti-Semitic and conservative ideas of Charles Maurras to the revolutionary theories of Georges Sorel and Leon Trotsky all had appeal. Although Trudeau hesitated between being a “philosopher” of the revolution or a “man of action,” he certainly chose action in the streets during the conscription plebiscite of 27 April 1942 and especially during the federal by-election in Outremont in November 1942 when he gave a fiery speech, reported in detail in Le Devoir, which ended with a call for revolution.

Then, the spirit of violent revolution passed, although Trudeau was involved in the Bloc Populaire Canadien, which had taken the lead in the anti-conscription campaign. Father d’Anjou pressed him to take on the editorship of a nationalist journal promoting the notion of Laurentia, which at this time meant to Trudeau a French-speaking autonomous state. Trudeau’s activism waned, however, as his law studies came to an end in 1943. Although he had disliked law school intensely, he finished first in his class. He continued to maintain close ties with Hertel, met several times with Abbé Groulx, favoured French marshal Philippe Pétain’s government at Vichy, and supported nationalist causes, but he moved to the sidelines. He appears to have wanted to escape and to seek a new experience, initially soliciting a diplomatic post and then applying to Harvard University for graduate work. In the fall of 1944 he obtained permission to leave the country in order to study politics and economics at Harvard.

The university made a deep impact on Trudeau, although he frequently resisted the Anglo-American liberalism that pervaded it in the mid 1940s. His views changed while he was there. He was influenced by the numerous European exiles, many of them Jewish, who taught him brilliantly, notably Wassily W. Leontief, Joseph Alois Schumpeter, Carl Joachim Friedrich, and Gottfried Haberler. He heard about John Maynard Keynes for the first time and came to believe that his earlier classical education had been sadly deficient. He was also intrigued by liberal and democratic traditions and the separation of the spiritual from the secular in public life. He wrote in his notebooks, “The spiritual will have [the] decisive voice in education, consultative in action.” And he began to reconsider what World War II had meant for the broader civilization he was learning to know better. He wrote to his girlfriend Thérèse Gouin that he had kept his eyes on his desk while “the greatest cataclysm of all time” occurred. Puzzled, she asked what he meant. He replied, “The cataclysm? It was the war, the war, the WAR!” In the mid 1940s Trudeau wanted to marry Gouin, a psychology student at the Université de Montréal, the daughter of Liberal senator Léon Mercier-Gouin and the granddaughter of former premier Sir Lomer Gouin, but she broke off the relationship, principally because of his intensity and his opposition to her desire to study psychology and continue her own psychoanalysis.

In 1946 Trudeau left Harvard with many questions, an abiding interest in the promise of Keynesian economics for democratic renewal, and a new scepticism about his earlier education and beliefs. He decided to continue his studies in France, where he audited courses at the Institut d’Études Politiques de Paris, but where his major interest was the stirring debates among French post-war intellectuals, particularly among Catholics. Like Trudeau, Mounier was discarding corporatist, collectivist, and elitist aspects of pre-war personalism and shaping the doctrine for the post-war era. Trudeau enthusiastically attended lectures and meetings with Mounier and other Catholic intellectuals such as Pierre Teilhard de Chardin and Étienne Gilson. In a nation where communism thrived, Mounier’s attempt to find a balance between Soviet communism and Christianity impressed Trudeau, who decided that his proposed Harvard doctoral thesis should explore the potential areas of reconciliation between Catholicism and communism. From Paris he went to England in the fall of 1947 to study at the London School of Economics and Political Science. He quickly found that the eminent Labour Party intellectual Harold Joseph Laski shared his belief in the need for reconciliation between the west and Soviet communism and his doubts about the fervent anti-communism of Britain’s Labour government. Laski and the London School of Economics had a greater intellectual influence on him than his experiences in Paris, particularly in spurring his understanding of democratic socialism.

While his views were changing, Trudeau kept in touch with old friends in Quebec. He produced articles for the conservative Catholic Notre Temps (Montréal) in 1947, denouncing Prime Minister Mackenzie King, the arbitrary internment of Quebec Fascist leader Adrien Arcand* from 1940 to 1945, and the policies of the wartime government; simultaneously he argued for increased civil liberties, greater democracy, and more state involvement in economic life. There was an opacity in his writings; highly expressive language accompanied sometimes contradictory and confused views. To Lessard, he still wrote about the dream of Laurentia. After his London experience, he set out on a world tour in the spring of 1948. He justified the trip as research for his thesis, but there is little evidence of sustained work on the topic. He would never complete his doctorate, although he had received master’s degrees from Harvard and the London School of Economics. His journey was, however, an adventure during which he was thrown into a Jordanian jail as a Jewish spy, eluded thieves at the ziggurat at Ur in Iraq, witnessed wars in India, Pakistan, and Indochina, and barely escaped Shanghai, China, as it fell to Mao Zedong’s Communist army. Finally, he returned home to Montreal in May 1949 with a broad international experience, a solid knowledge of political economy specifically and the social sciences more generally, and a better appreciation of the possibilities of the law than he had had when he left the Université de Montréal as a celebrated but disappointed student.

In his own words Trudeau came back to a Quebec that was at “a turning point in [its] entire religious, political, social, and economic history.” He believed he discovered that decisive moment when he set off with Gérard Pelletier, a journalist with Le Devoir, to the Eastern Townships to join striking asbestos workers. Pelletier, who had often met with Trudeau in Paris, sided with Jean Marchand*, general secretary of the Canadian and Catholic Confederation of Labour, to press the cause of the strikers. The Union Nationale government in Quebec under Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis* reacted harshly to what it considered an illegal strike, but the Catholic clergy was divided on the issue. Wearing a scraggly beard, Trudeau played a small role, marching in a head-cloth and shorts. The amused miners called him St Joseph; the police arrested him. He soon returned to Montreal, but the strike profoundly affected him as he linked the evidence of working class action with his study of socialism, labour, and democracy. He met with members of the Canadian Congress of Labour and considered becoming its research director. During the following years he acted as legal counsel for unions throughout the province. In 1956 he would use the strike as a prism through which to illuminate the social and economic development of Quebec in his most sustained analytical work, a chapter in La grève de l’amiante (Montréal); the volume, which he edited, would present a detailed study of the asbestos strike.

Trudeau now believed that in the new Quebec the “social” should take precedence over the “national,” as his close friend Pierre Vadeboncoeur put it in the summer of 1949. Although Notre Temps, in which he had invested $1,000 in 1944 and which had published his major articles while he was in Europe, became increasingly drawn to Duplessis’s conservative nationalism, Trudeau moved in a completely different direction, towards the democratic socialism whose main Canadian expression was the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation. In the federal election of June 1949, he had been this party’s agent in the riding of Jacques-Cartier. As the attraction of socialism intensified, his affection for Quebec nationalism waned, especially since nationalism was so strongly represented by the conservative forces within the Quebec Catholic Church and, of course, by the Duplessis government, which he regarded as archaic and out of step. Like many of his generation, he was angry. Once again, he left Quebec.

In the late summer of 1949 Trudeau became a federal public servant in the Privy Council at Ottawa. Although the choice shocked Pelletier and other friends, Ottawa beckoned to many highly educated francophones. Trudeau’s experience there was important in providing him with a better understanding of the character of Canadian federalism. He came to believe that it had played an important part in limiting extremes while simultaneously affording the opportunity for political experimentation and the correction of social inequities. While retaining the notion that provincial and federal governments had clearly delineated responsibilities, he shared the assumption, common in Ottawa, that Keynesian economics provided the federal government with the opportunity and the responsibility to intervene in the economy to assure prosperity and security. He worked long hours and quickly impressed his superior, Robert Gordon Robertson, and his colleagues with his intelligence and diligence. His socialism and, even more, his criticism of Canada’s Cold War alliances did not, however, fit well with Ottawa’s mood as Canada entered the Korean War in 1950. He chafed against the anonymity imposed on public servants. He also concluded that Ottawa was an unwelcoming “English capital” and spent most weekends in Montreal. Relief from Ottawa’s bleakness came as well from an intense romance with Helen Segerstrale, a young employee of the Swedish embassy. In the summer of 1951, after writing an anonymous attack on Canadian involvement in the Korean War, he quit his job. His romance ended when Segerstrale refused to convert to Catholicism. Unlike many of his francophone colleagues, Trudeau would remain a devout Catholic.

In Montreal in 1950, Trudeau had begun discussions with Pelletier and, later, with others about the establishment of a journal similar to Mounier’s Esprit (Paris), which had enormous influence on Catholic thought in post-war France. Pelletier had quickly persuaded Trudeau to become his principal partner in the creation of Cité Libre (Montréal) in the summer of 1950. He had a more difficult time getting his other colleagues to accept the wealthy and idiosyncratic Trudeau, who many believed would be “a disturbing influence.” Writing in the 1980s, Pelletier would admit that he had been.

Despite the uncertain nature of his start at Cité Libre, Trudeau became closely identified with the magazine in the 1950s. His co-editorship carried him to the heart of the opposition to the Duplessis government and permitted him, in Pelletier’s words, “to find his place ... in his generation.” His presence was dominant from the first issue, when he wrote emotional but anonymous tributes to his mentors Mounier and Laski, both of whom had died recently. He also wrote an article on “functional politics,” the first draft of the political program that he would develop in the 1950s. He urged Quebec to open itself to the world while still bearing “witness to the Christian and French fact in America.” He concluded with a call “to borrow the ‘functional’ discipline from architecture, to throw to the winds those many prejudices with which the past has encumbered the present, and to build for the new man.” The new generation should break the old taboos: “Better yet, let’s consider them null and void. Let us be coolly intelligent.”

Things were not always cool. Cité Libre appeared irregularly, its finances were always wobbly, and it quickly attracted criticism. The conservative historian Robert Rumilly* warned Duplessis that Cité Libre’s editors and contributors were “extremely dangerous” and “subversive.” Trudeau’s earlier mentor Father d’Anjou wrote a savage attack on an article of his that claimed priests had no more of a divine right than politicians. As a result of these and other comments, Archbishop Paul-Émile Léger of Montreal summoned Pelletier and Trudeau. Despite some insolence on Trudeau’s part during the meeting, Léger did not condemn the review, an action that could have had dire consequences. Cité Libre survived. Through his work as editor, Trudeau came to know the leading intellectuals of the time and Radio-Canada sought out Cité Libre authors and editors to comment on public affairs. English Canadian intellectuals became curious about the publication and invited Trudeau to their gatherings, especially the conferences of the Canadian Institute of International Affairs and the Couchiching Institute on Public Affairs. His flawless English, familiarity with contemporary social science, and striking physicality intrigued those who encountered him in such settings. So did his thoughts.

A close reading of Trudeau’s writings and speeches in the 1950s reveals that some of his ideas changed little, others much more. He remained consistently wary of the Cold War and sympathetic to the view of Le Monde (Paris) and others that there was a “middle way,” between the fervent anti-communism of North American governments and the stern communism of Joseph Stalin, a view rarely heard in English Canada or in the Quebec Catholic Church at that time. He also continued to call for francophones to be “functional,” which towards the end of the decade came to mean a strengthening of the technical, scientific, and social science sectors of Quebec society, especially in the universities. However, his strong anticlericalism abated when it became clear that the church itself faced enormous strain in adapting to the rapid changes in Quebec as the economy became more sophisticated and modern communications, especially television, transformed daily life. He began to shift his attention to political institutions, notably the governments in Quebec City and Ottawa. He considered the provincial administration corrupt, autocratic, and socially regressive; the federal, he complained, ignored the French fact even when Louis-Stephen St-Laurent was prime minister, too casually embraced the American approach to the Cold War, and too often ignored the constitution. The last grievance became evident when Trudeau, to the surprise of many of his friends and some of his enemies, supported the Duplessis government’s rejection of federal grants to universities on the grounds that “no government has the right to interfere with the administration of other governments in those areas not within its own jurisdiction.” Yet even in agreeing with Duplessis he condemned his government. “Let Mr. Duplessis establish an administration as efficient and honest as the federal government, and we shall then consider the rivalry to be a fair one.”

Trudeau, then, was never predictable. A social democrat, he became increasingly sceptical of the CCF and disappointed his friend Thérèse Casgrain [Forget*], the provincial party leader, with his unwillingness to make a fuller commitment. A strong opponent of Duplessis and the Union Nationale, he refused to join the coalition that emerged under the leadership of the Liberal Party to defeat the government. The essay he contributed to the study of the asbestos strike of 1949, published in 1956, revealed his deep distrust of the Quebec Liberal Party and his disillusionment with the detritus of earlier political and ideological battles. The past, it seemed, bore mainly bad lessons for the future. In a 1958 article, “Some obstacles to democracy in Quebec,” published in the Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science (Toronto) and in French in his Le fédéralisme et la société canadienne-française (Montréal, 1967), he wrote, “Historically, French Canadians have not really believed in democracy for themselves; and English Canadians have not really wanted it for others.” He increasingly argued that both English and French Canadians were imprisoned in their past, the English in the fusty British imperial tradition and the French in a sterile clerical nationalism, exemplified in his mind by the attacks on Cité Libre from conservative church voices such as Father d’Anjou or historian Rumilly. His assaults on Quebec nationalism, which had been less virulent than those of other Cité Libre authors in the early 1950s, now became intense as he blamed nationalism for closing the windows to the fresh winds of the modern world. He became an eloquent defender of federalism as a “safety valve” through which individuals and groups might obtain redress denied by an autocratic provincial government and a strong supporter of the courts which, during this decade, began to establish a Canadian tradition of civil liberties. Like McGill University law professor and poet Francis Reginald Scott* and journalist Jacques Hébert, he looked to the courts to protect individual rights that, in the past, had so often been denied.

As Trudeau became clearer in his writings, he seemed more muddled in politics. In 1956 he had joined with Pelletier, Hébert, journalist André Laurendeau*, and others who lacked party affiliation to form the Rassemblement, which he would describe in his memoirs as a “fragile and short-lived body [that] undertook to defend and promote democracy in Quebec.” While others began to rally behind the Liberal Party to defeat Duplessis, he continued to urge a non-partisan coalition. His vehemence in promoting the Rassemblement angered his friends both in the Quebec wing of the CCF, known since 1955 as the Parti Social Démocratique du Québec, and among the reformers who believed they were taking control of the provincial Liberal Party. He attended the Quebec Liberal Party’s convention of 1958 and dismissed it as undemocratic. As the Rassemblement crumbled, he turned to a new grouping, the Union des Forces Démocratiques, which in October 1958 issued “Un manifeste démocratique,” written mainly by him, in Cité Libre. Now a familiar figure on Quebec television and a target for attack not only by Duplessis but also by Quebec socialists, Trudeau took the leadership of the union. His decision to accept the position seemed a whimsical gesture to many. A student newspaper, the McGill Daily (Montreal), summarized the general perception of Trudeau, stating that “the author is considered to be a brilliant man but to many [he] still remains a dilettante.” His ideas were interesting but his influence was limited.

The death of Duplessis in September 1959 dramatically changed the political landscape; the impact of his departure was amplified when his successor, Paul Sauvé*, suddenly died on 2 Jan. 1960. The ambitious and the practical rallied to the Liberals under Jean Lesage*, but Trudeau did not follow. He continued to lead the Union des Forces Démocratiques and to urge unsuccessfully the formation of a new coalition. On the eve of the provincial general election of 22 June he finally and grudgingly endorsed the Liberals in Cité Libre. His reservations about them grew after the election even though Lesage’s determination to secularize Quebec society had his solid support. The administration was progressive but also nationalist and its nationalism increasingly troubled him. Although the Lesage government’s nationalism or “neo-nationalism” differed from that of Duplessis in its secularism and its fervent embrace of modernity, Trudeau saw in the official rhetoric and actions a nationalist approach in which the state was identified with the “nation.” These doubts augmented during his regular meetings with René Lévesque* on weekends when the new minister of public works and hydraulic resources returned from Quebec City. To Trudeau, Lévesque’s anger and his determination to proceed with the nationalization of hydroelectricity seemed irrational. Trudeau believed that secularization and modernization were imperative but also that Quebec should, as he wrote in Cité Libre in 1961, “open up the borders.” “Our people,” he argued, “are suffocating to death!”

That year Trudeau finally obtained the position with the faculty of law at the Université de Montréal which had been denied him by the Duplessis government. He found the atmosphere “sterile,” with “the terminology of the Left ... serving to conceal a single preoccupation: the separatist counter-revolution.” In 1962 he wrote a bitter attack on Quebec nationalism and separatism that placed the blame for these movements squarely on the intellectuals. In “La nouvelle trahison des clercs,” published originally in Cité Libre and six years later in English in Federalism and the French Canadians (Toronto), he denied that decolonization was relevant to Quebec because the province had rights that colonists had never possessed. Nationalism had produced the worst wars of the century and the quest for “complete sovereign power” was inevitably a “self-destructive end.” Nationalism, then, was reactionary, an attempt by a new francophone bourgeois elite to consolidate its power through such devices as the nationalization of hydroelectricity. “French Canadians,” he wrote, “have all the powers they need to make Quebec a political society affording due respect for nationalist aspirations and at the same time giving unprecedented scope for human potential in the broadest sense.”

The Quebec election of November 1962 with the Liberal party’s slogan “Masters in our own house” and its major issue, the nationalization of hydroelectricity, placed Trudeau in a role he had often held, that of a critical voice without a party. After Lesage’s triumph, he considered turning to federal politics at the urging of Jean Marchand, who had developed ties with the Liberals under party leader Lester Bowles Pearson. These plans collapsed when Pearson changed his position on nuclear weapons in January 1963. The reversal prompted an angry denunciation of Pearson in Cité Libre, where Trudeau echoed Vadeboncoeur’s memorable description of Canada’s Nobel Peace Prize winner as the “defrocked prince of peace.” Other disappointments came with Cité Libre, whose expanded editorial committee bickered constantly.

More difficult were his breaks with Vadeboncoeur, perhaps his closest friend from childhood and adolescence, and Hertel, his early mentor. Both approved of separatism, but Trudeau became particularly enraged by an article in which Hertel seemed to advocate the assassination of Laurendeau for having accepted, with Arnold Davidson Dunton*, the co-chairmanship of the royal commission on bilingualism and biculturalism in July 1963. He publicly attacked his former teacher.

Long ago Trudeau had heeded Hertel’s call for revolution, but he now believed that what Hertel and Vadeboncoeur thought revolutionary was truly reactionary, an unrealistic approach to a world where science and social science offered real prospect for positive change. With some new friends – economist Albert Breton, sociologists Raymond Breton and Maurice Pinard, lawyers Marc Lalonde and Claude Bruneau, and psychoanalyst Yvon Gauthier – he issued a manifesto in both languages in May 1964. It appeared in English as “An appeal for realism in politics” in Canadian Forum (Toronto). The group denounced the lack of realism in Quebec politics, argued that the traditional nation state was obsolete, and announced their refusal “to let ourselves be locked into a constitutional frame smaller than Canada.”

Canada, however, seemed threatened as Pearson’s government struggled with the pace of change in the mid 1960s. Hopes for an agreement on a way to amend the constitution through the so-called Fulton–Favreau formula collapsed, scandals undermined the cabinet ministers from Quebec, and Pearson groped for a new path through which his government could find a response to the challenge of Quebec nationalism and separatism. Trudeau had little faith in the royal commission on bilingualism and biculturalism, which he correctly believed was moving towards the recommendation of special status for Quebec.

In these circumstances Trudeau’s long apprenticeship came to an end. On 10 Sept. 1965 Marchand, Pelletier, and he announced that they would be Liberal candidates in the federal election which Pearson had called three days earlier. The declaration stunned most of their Cité Libre colleagues, who expressed their disapproval in the magazine’s pages and in later articles published elsewhere, and some of Trudeau’s English Canadian socialist friends. Vadeboncoeur and other nationalists and separatists scorned Trudeau’s decision. On the whole, the English press welcomed the “three wise men” to the Liberal team. The French press called them simply “les trois colombes” (the three doves). The eloquent labour leader Marchand was the prize candidate and it was he who insisted that the unpredictable Trudeau, who had so recently denounced Pearson, accompany him to Ottawa. After some delay, the party opened the strongly Liberal seat of Mount Royal for Trudeau. He won it with a large margin on 8 November and would hold it until the end of his political career in 1984. The Liberals failed to win a majority, however, and parliamentary disorder persisted.

Initially hesitant, Trudeau refused Pearson’s request that he be the prime minister’s parliamentary secretary. An angry Marchand rebuked him and Trudeau then accepted the position; his precise duties were not defined. Gradually, Trudeau found others in Ottawa who shared his concern that the government’s policy towards Quebec was one of drift. He met regularly with Lalonde and with public servants such as Peter Michael Pitfield and Allan Ezra Gotlieb. They began to craft a more coherent response to Quebec’s constitutional challenges, one that rejected what they perceived as the weakness embodied in the cooperative federalism of the first Pearson years. Trudeau became identified by political commentators as, potentially, the most significant of the “three wise men.” He did little publicly in 1966 to justify these expectations, but Marchand had noticed that his colleague possessed political magic. He told Laurendeau he “bet his shirt” that Trudeau would quickly become the Liberals’ “big man in French Canada, eclipsing all the others.” Soon he did.

The close attention Trudeau had paid to the constitution while working in the Privy Council in 1949 suddenly became valuable political capital as constitutional discussions reached a deadlock in 1966. In March he and Marchand gained control of the Quebec wing of the federal Liberal Party, which had established its own administration. At its first meeting the Quebec section supported motions drafted by Trudeau condemning “special status” or “a confederation of ten states” and approving the concept of a “bill of rights” within the constitution. On 5 June 1966 the provincial Liberals went down to a stunning defeat. The victor, Daniel Johnson* of the Union Nationale, was much more ambiguous about Canada. His slogan, “Equality or independence,” directly challenged the platform drawn up by Trudeau for the Quebec federal Liberals. Behind the scenes in Ottawa, Trudeau worked with Lalonde and, especially, Albert Wesley Johnson, assistant deputy minister in the Department of Finance, to draft a statement presented by finance minister and receiver general Mitchell William Sharp* at the federal–provincial conference held in September. It rejected special status for Quebec and opting out of federal programs by Quebec alone. Johnson’s thrust forward met a well-conceived counterattack.

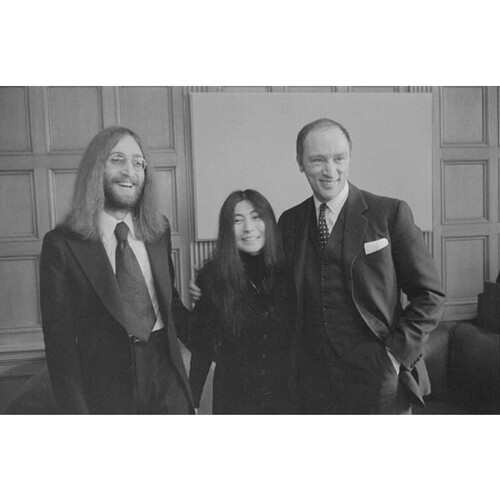

Trudeau was making his mark privately, not publicly, and he remained largely unknown in English Canada. Yet events were determining his fate. Centennial year, 1967, brought not only the celebration of Canada with its wildly successful Expo 67 in Montreal but also constitutional crisis as Johnson pressed his demands. On 4 April 1967 Pearson appointed Trudeau minister of justice and attorney general, strengthening the left wing of the Liberal Party and his government’s constitutional expertise at federal–provincial meetings. Trudeau quickly went to work and displayed an astonishing discipline that shocked bureaucrats who had heard the many rumours about his playboy lifestyle. He concentrated primarily on the constitution and the much-delayed reform of the Criminal Code. The 47-year-old bachelor announced his plan to decriminalize homosexual acts between consenting adults, allow for easier divorces, and permit abortion if the mother’s health was endangered. In a Canada that was suddenly becoming permissive and liberal, he struck the loudest notes. The house unanimously passed his divorce reforms in December 1967, shortly after Pearson had declared his intention to resign as soon as a new party leader was chosen.

The race for a successor began immediately. Pearson told Marchand he must run because the Liberal principle of alternation between French- and English-speaking leaders and the Quebec crisis required that he do so. Lalonde, Pitfield, and Trudeau’s assistant, Eddie Rubin, were already considering how Trudeau might be drafted. In January 1968, after a vacation in Tahiti, where he had become entranced with the stunning Margaret Sinclair, daughter of a former Liberal cabinet minister, Trudeau met with Marchand and Pelletier. Marchand would not run; Trudeau must. Typically, Trudeau hesitated even though he had seriously considered the prospect. The Conservatives under their new leader, Robert Lorne Stanfield*, were ahead in the polls; there were powerful Liberals contesting the race, including the wily veteran Paul Joseph James Martin, finance minister Sharp, senior cabinet minister Paul Theodore Hellyer, and several other experienced candidates; and, finally, Trudeau feared losing the privacy he had long cherished. Yet he had dreamed of a public career since adolescence and he knew that, whatever its deficiencies, the royal commission on bilingualism and biculturalism was correct in stating that Canada was going through the greatest crisis in its history. It was no time to step aside.

Many agreed. Leading Canadian journalist Peter Charles Newman began to tout Trudeau in his columns. Marchand, who was a superb political organizer, told Trudeau that he would “handle” Quebec for him but that Trudeau himself would have to “handle” the rest of Canada. He did so brilliantly. In late December he had captured attention with his televised comment that “there’s no place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation.” He then received an enormous boost from Pearson, whom he had so often criticized publicly and privately. Despite the misgivings of other leadership candidates, the prime minister sent him on a politically valuable tour of provincial capitals and gave him the principal seat at the federal–provincial constitutional conference of 5–7 February 1968. Johnson had expected Pearson to be his debating opponent, but he faced Trudeau, whose biting tones, quick repartee, and well-defined positions quickly captured attention. Trudeau’s sculpted face, penetrating eyes, and confident rhetoric dominated the nightly news. Marchand concluded that “at the beginning of February he was really created.”

Not all were pleased with the creation. Claude Ryan* of Le Devoir strongly criticized Trudeau’s performance at the conference and his rigidity on the question of special status for Quebec and constitutional revision more generally, which became a frequent complaint of others contesting the leadership. His opponents were already reeling from the publicity Trudeau had garnered. Journalists had dubbed the resulting enthusiasm “Trudeaumania” when Trudeau announced his candidacy on 16 Feb. 1968. Very quickly he rose to the top in the polls, but more important to his ultimate success was the defeat three days later of the Liberal government in the House of Commons on a money bill introduced by Sharp. Pearson returned from holidays to save the situation, but Sharp’s leadership campaign was doomed. On 3 April, the eve of the convention, Sharp withdrew and announced that he was supporting Trudeau. Powerful Newfoundland premier Joseph Roberts Smallwood also offered valuable backing that same night, declaring before a riotous crowd that “Pierre is better than medicare – the lame have only to touch his garments to walk again.”

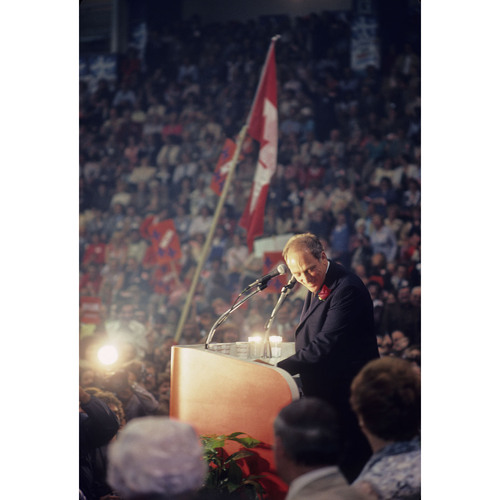

Trudeau needed miracles nonetheless. Robert Henry Winters* strongly challenged him after he overcame Hellyer on the second ballot. The fourth and final ballot saw Trudeau win with 1,203 votes to 954 for Winters and 195 for John Napier Turner, who had refused to withdraw. On 20 April Trudeau became prime minister and he soon called an election for 25 June. The leadership campaign had had the desired effect of boosting Liberal support and the election campaign saw the dour Stanfield overwhelmed as Trudeau, to the media’s delight, shattered Canada’s conservative electoral mould by kissing beautiful women, not babies, and doing jackknife dives clad in a European men’s bikini. His many years of strenuous physical activity had impressively hardened his body and given him a quickness and fluidity of movement. His deserved reputation as an excellent swimmer and diver, skilled canoeist, practitioner of judo, and intrepid adventurer appealed to the young and the press. But there was substance too. He eloquently attacked the Conservatives and the New Democratic Party, accusing them of favouring a “two nations” approach, and he directly challenged Quebec’s international aspirations. His firmness gained credibility when, on the night before the election, Saint-Jean-Baptiste day, he took his place on a Montreal reviewing platform. A mob of students and separatists threw bottles, eggs, and stones, but Trudeau would not budge. Any doubts in English Canada about his personal courage, based on his lack of wartime service, seemed to disappear. He savoured his greatest electoral victory as his party won 154 seats, including 56 of the 74 seats in Quebec, the Conservatives only 72, the NDP 22, and the Ralliement des Créditistes 14. One Liberal-Labour member and one independent were elected, for a total of 264.

In the campaign Trudeau had promised a “just society,” but contemporary observers remarked on the vagueness of his policy proposals apart from those on constitutional issues. As a scholar and a polemicist, Trudeau had urged greater democracy within political parties. His attack on Pearson in 1963 had rested largely on the argument that Pearson had not consulted his party before he changed the Liberals’ stance on nuclear weapons. Trudeau stressed political education and participation despite the doubts of Marchand and others. Lacking an explicit platform developed by a policy convention, he advocated the concept of “participatory democracy.” On a range of issues, there would be broad public consultations that would serve to inform the citizenry while creating legitimacy for government action. The approach was not a success. It would be adopted most notably in a foreign policy review; the result, published in 1970, was a series of pamphlets whose content was so bland that the critical issue of Canadian–American relations went unmentioned.

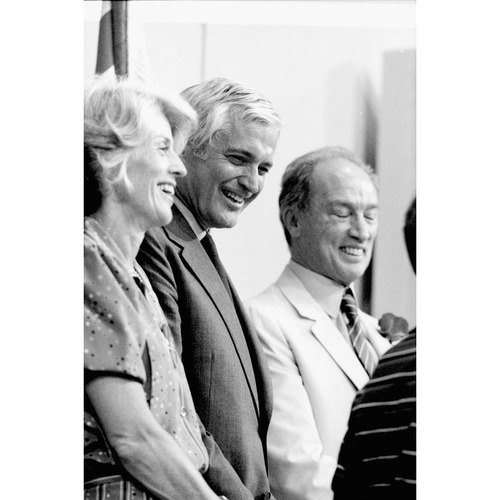

This gap between hope and disappointment became quickly evident after the election campaign. As journalist Richard Gwyn wrote, “The kissing stopped almost as soon as the ballots were counted.” Trudeau did receive some praise for the presentation of his cabinet on 5 July 1968, even from Claude Ryan, who commended him for the strongest-ever francophone presence. The cabinet included Léo-Alphonse Cadieux in national defence, Pelletier as secretary of state, Jean-Luc Pépin in industry and in trade and commerce (later combined as one ministry), and Marchand in forestry and rural development (the following year he would become minister of regional economic expansion). Outside the cabinet, Lalonde was made chief of staff and Pitfield took on major responsibilities in the Privy Council Office. The appointments signalled three important themes of Trudeau’s tenure as prime minister: the strengthening of the francophone presence in Ottawa, “French power” as it came to be called; the emphasis on regional economic initiatives or redistributive policies; and the streamlining of the Ottawa bureaucracy and political decision-making through the introduction of modern organizational concepts such as systems analysis. Trudeau would take special pride in the adoption of the Official Languages Act in 1969, a measure which reflected his political rhetoric and private beliefs. In these areas, the federal government had much freedom; in contrast, the unfinished business of the constitution required the cooperation of the provinces.

Daniel Johnson had died in September 1968. His successor, Jean-Jacques Bertrand*, reaffirmed minority-language education rights in response to bitter confrontations in Saint-Léonard (Montreal), where a heavy concentration of Italian immigrants wished to educate their children in English. The second volume of the royal commission on bilingualism and biculturalism had just appeared and had called for federal support for minority-language education and for a constitutional guarantee of parental choice in the language of education. As the Union Nationale divided on the subject, the Quebec Liberals fractured. René Lévesque had left the party the previous year and he founded the Parti Québécois, which held its first convention in October 1968. Bertrand was weak, however, and in April 1970 the Liberals under lawyer-economist Robert Bourassa won a decisive victory, which appeared to open the path to resolving the thorny issues that had plagued constitutional discussion since the Johnson–Trudeau confrontation. In June 1971 the path led to Victoria, where the federal government and the premiers agreed on the Canadian Constitutional Charter, a compromise that, understandably, satisfied no one but which offered resolutions to the differences over a formula to amend the constitution, language rights, social spending, and the entrenchment of individual rights. Trudeau admitted the limitations but said at his final Victoria press conference that if all governments accepted the charter, as was required for its enactment, “we’ll all wear a crown of laurels.” Bourassa flew home the following day to a storm of criticism, since the agreement had not met Quebec’s demands concerning greater provincial control of social policy. One week later he announced he would not present the charter to the National Assembly of Quebec. For Trudeau, it was a defeat and even a betrayal by Bourassa who, he believed, had promised his support.

Trudeau’s doubts about Bourassa had derived in large part from the October crisis in 1970, which remains, probably, the most controversial event of his prime ministerial tenure. The crisis began with the kidnapping in Montreal of British trade commissioner James Richard Cross by members of the Front de Libération du Québec on 5 Oct. 1970. Although there had been thefts of arms and rumours of possible kidnappings, the police forces at all levels were unprepared for the challenge and the governments of Quebec and Canada initially responded by agreeing to some of the kidnappers’ demands, notably the reading of the FLQ manifesto and a guarantee of their safe passage.

Then on 10 October the Chénier cell of the FLQ seized the Quebec minister of labour and immigration, Pierre Laporte*, at his suburban home in Saint-Lambert. The brazen act stunned the country. The Bourassa government hesitated. Trudeau had been irritated by the earlier decision of Sharp, the secretary of state for external affairs, to agree to the reading of the FLQ manifesto by Radio-Canada. Others, including Ryan and Lévesque, urged conciliation and considered calling for Bourassa to stand aside for a new coalition government. On 15 October the federal cabinet met to consider a request from Bourassa that Ottawa come to Quebec’s assistance. Marchand took the lead by warning that the situation was “much more serious” than had been believed. He claimed that the FLQ had two tons of dynamite ready to explode and urged an immediate raid on the organization, whose numbers he estimated at anywhere from 200 to 1,000. Trudeau agreed. According to cabinet reports, he concluded “the longer we gave opinion makers in Quebec, the more we stood to lose,” a bitter reference to a document published that day in Le Devoir. Signed by Lévesque, Ryan, and others, it referred to the “semi-military rigidity ... in Ottawa” and used the term “political prisoners” for jailed FLQ members. Moreover, the prime minister advised that Bourassa did not want backbenchers “to sit around too long.” They were “falling apart.” This concern reflected Trudeau’s belief that the Quebec Liberal Party was not united in its opinions. In answer to the Quebec government’s request, the Canadian armed forces were called in to assist the police. Trudeau worried about what future civil libertarians might think but, after long debate, the War Measures Act was invoked on 16 October. The following day Laporte, whom Trudeau had known well, was found dead in the trunk of a car. The strong response had broken the momentum of the FLQ, however. Cross was released on 3 December and Laporte’s murderers were captured on 28 December.

Trudeau’s decision to suspend the normal legal process haunted him and it swelled the ranks of his detractors on the left and among Quebec nationalists and separatists. When he wrote his memoirs, he would defend the action, first, as the only one possible when the “more interested parties,” the Quebec premier and the mayor of Montreal, pleaded for federal assistance and, secondly, as a step necessary to “prevent the situation from degenerating into chaos.” The cabinet record and other evidence support his later claim that he had worried about the implications. They also suggest that the role of Marchand, who had overstated the threat posed by the FLQ, was decisive. However, information at the time was sketchy, confidence in the Bourassa government was lacking both in Ottawa and Quebec, and the War Measures Act, with its broad powers, was the sole means to act quickly.

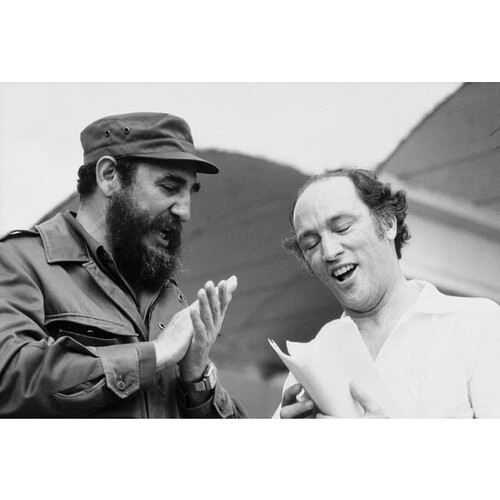

The decision left an ambiguity concerning Trudeau’s regard for civil liberties. His famous reply when asked how far he would go, “Well, just watch me,” has lingered as evidence of autocratic tendencies. Moreover, many innocent people were arrested – some Trudeau knew well – and the police were careless in their use of their new powers. Although he had long been active in civil liberties movements and legal cases, he had also praised autocratic regimes in the Soviet Union in 1952 and China in 1960 and maintained a warm relationship with Cuban leader Fidel Castro. His views fitted badly into the grammar of human rights that would be developed in the late 20th century by international non-governmental organizations such as Human Rights Watch, yet he would argue, as would his principal secretary, Thomas Sidney Axworthy, in 2003 that what is needed is “an agreed-upon framework of law in order for us to make all of our individual choices.” Political and civil rights should be protected with whatever means were available if they were in danger. Hence in his memoirs he defended “Well, just watch me” as an indication of his determination to maintain the rule of law in Canada. Opinion remains divided over Trudeau’s decisions not to negotiate and to invoke the War Measures Act, but he is correct in stating that the terrorist threat abated and the FLQ disappeared after October 1970. Nevertheless, the death of Laporte, the government’s response to the crisis, and the army in the streets marked a decisive moment in Trudeau’s political life and that of his government. The buoyant hopes of the 1960s seemed to dissolve and the 1970s would be a difficult decade for Trudeau and other world leaders as the post-war boom came to an end.

Despite the opposition of many opinion leaders in English and French Canada to the government’s actions, the immediate effect of the crisis was a surge in support for the government from across the country; 87 per cent of Canadians, with little difference between anglophones and francophones, expressed their approval of its actions. Enthusiasm for Trudeau and the Liberals was reinforced when he suddenly married 22-year-old Margaret Sinclair on 4 March 1971. The event attracted international attention.

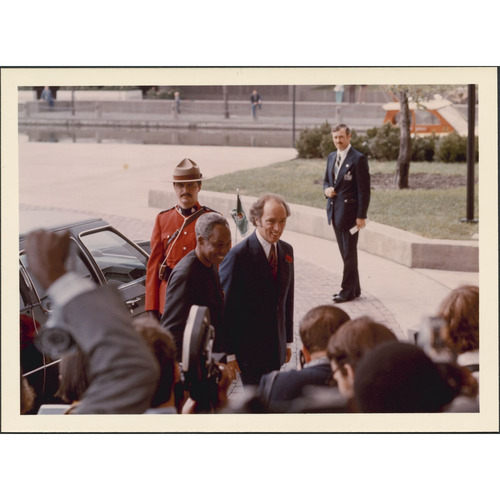

The completion of Trudeau’s foreign policy review in 1970 had resulted in few changes of direction. Diplomatic relations were established with China that year as they had been with the Vatican in 1969; the military commitment to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization was reduced; and Canada’s foreign service accepted the need for bilingualism. Trudeau was initially so sceptical of the Commonwealth of Nations that only the strongest pressure from his staff persuaded him to attend its Singapore conference in January 1971. He nevertheless played a major role there in mediating the bitter disputes about South Africa. He also travelled to the Soviet Union, western Europe, Australia, and the United States. His relationship with the American administration was bad, however, principally because President Richard Milhous Nixon disliked him profoundly and Secretary of State Henry Alfred Kissinger played to Nixon’s hostility and vanity. In turn, Trudeau barely concealed his distrust of American foreign policy. Yet despite nationalist calls for disengagement from the United States and dreams of a “third option,” through which Canada would establish closer relationships with Europe and the developing world, the American presence remained dominant albeit difficult.

By 1972 the Canadian government was stumbling, as were the governments of other western countries, in trying to adjust to new international circumstances, particularly the combination of inflation and unemployment that challenged traditional Keynesian approaches to the economy. Ministers grumbled about Trudeau’s staff, which, they claimed, lacked political experience; Hellyer and Eric William Kierans* had left the cabinet complaining, respectively, about the lack of a housing policy and weak economic guidance; and others warned the prime minister that the Liberal grass roots were weak. Richard James Hardy Stanbury, the Liberal Party president, fretted in his diary about Trudeau’s refusal to go to party fund-raisers and to pamper volunteer officials. This aloofness mingled dangerously with Trudeau’s actions. Few believed he had really said “fuddle duddle” in February 1971 to an irritating Tory mp. His explanation amused many, but commentators and even some colleagues thought it reflected his disdain for parliament and its traditions. Although an excellent debater, Trudeau did not conceal his contempt for much of the discussion in the House of Commons and for most parliamentarians. When he called an election for 30 Oct. 1972, the polls initially suggested another Liberal victory, but there was no Trudeaumania. The government had disappointed many. As John Gray wrote in Maclean’s (Toronto), “the outstanding impression is that, with few notable exceptions, Trudeau has remarkably few political goals.” The campaign strengthened that belief with its uninspiring English slogan, “The land is strong.” The Liberal Party and Trudeau were not. On election night the Conservatives and the Liberals had to await a recount to learn who would form an administration. A chastened Trudeau then told the press that the government of the past four and a half years “was not satisfactory.”

The recount saved Trudeau, but he now headed a minority government with 109 seats to the Tories’ 107; the New Democrats under David Lewis* held 31 seats; the Social Credit Party had 15; one candidate was elected as an independent and another was elected with no designation. Trudeau quickly adjusted. He brought in new political advisers, slowed down the bilingualism program, and became warmer and less provocative in public appearances, when he was often accompanied by Margaret and baby Justin. He also moved to the left to maintain the support of the NDP. Some had said Trudeau was inflexible; his pragmatism was evident in the government’s creation in 1973 of the Foreign Investment Review Agency, which the left had long advocated. Similarly, the government responded to the energy crisis of 1973 with a highly interventionist policy that protected Canadians from world prices. It annoyed Albertans, but there were increasingly few Liberal votes there.

On 8 May 1974 Trudeau engineered the government’s defeat by producing a budget the opposition could not support. He made no mistakes in this election. He campaigned relentlessly, often in the presence of Margaret, who became a crowd favourite. Le Devoir spoke admiringly of the new “Trudeau Express,” his campaign by train through the Maritimes. The smashing victory of the Quebec Liberals in the provincial election of October 1973 seemed to help the federal Liberals. Moreover, Stanfield had made a fatal error by suggesting that inflation should be halted by a wage and price freeze. Workers feared the wage controls and the Liberals gained New Democratic votes when Trudeau ridiculed Stanfield’s proposal with the phrase “Zap! You’re frozen.” On election day, 8 July, the Liberals won a solid majority with 141 seats compared to 95 for the Conservatives and 16 for the NDP; the Social Credit had 11 and 1 independent candidate was elected. The Globe and Mail (Toronto), which, like nearly all Canadian newspapers, had supported the Conservatives, editorially declared the win “a personal victory” for Trudeau, a tribute not to “Trudeaumania,... but [to] the work, effort and energy that he put into his campaign.” Yet it correctly warned that Trudeau faced problems of “grave dimensions,” particularly “runaway inflation,” often referred to as stagflation, in which high unemployment was combined with historically high rates of inflation. The inflation was in part the product of the global energy crisis whose political reflection in Canada was the absence of Liberal seats in Alberta.

Trudeau privately shared these concerns and the victory’s glow soon dimmed, especially at 24 Sussex Drive. “My rebellion,” Margaret Trudeau would write in 1979, “started in 1974.” The day after the election in which she had campaigned so well, “something” in her “broke”: “I felt I had been used,” she explained. Despite her reluctance, Trudeau and his political advisers had thrust her to the forefront of the campaign even though she was emotionally fragile after childbirth. The next three years were excruciatingly difficult for Trudeau personally as his marriage came undone in embarrassing bursts in the media. The couple would separate on 27 May 1977, with Trudeau retaining custody of their three sons. His aides quickly noted how his concentration had diminished and how his usually assiduous work habits had altered under the strain. His attempt to impose order once again on the chaos of a government’s daily life – steps which included making his friend Pitfield clerk of the Privy Council – could not cope with the rapid pace of change in the mid 1970s. A traditional Keynesian, Trudeau struggled to make sense of stagflation. He tried to establish a separate economic advisory group to counter the Department of Finance, which he distrusted. In September 1975 John Turner resigned as finance minister and an increasingly desperate Trudeau announced the creation of the Anti-Inflation Board to establish wage and price controls. It was a deed he had promised only a year before that he would never do.

Perhaps because of his personal problems but more likely because he believed a fundamental restructuring in the international order was near, Trudeau became more philosophical and more insistent that his government look towards the future. In a media interview of 28 Dec. 1975 he warned that the new controls reflected the failure of the “free market system” to work. The Canadian business press reacted in horror to these remarks and denounced his assessment. Like Pitfield, Trudeau was intrigued with the projections of futurists such as the members of the Club of Rome and the possibilities of systems analysis to improve government decision making. In this spirit, he wrote to one of his ministers, Alastair William Gillespie, in 1976 that “if we yield to the temptation of concentrating on today, we will default [on] our major responsibility to our children and to hundreds of millions elsewhere in the world who look to Canada with trust and who hope that we will contribute to a stable and just world order.... We can shape the changes that face us; we can influence the future that awaits us.”

If the economy was perplexing, Quebec was disappointing for Trudeau. After his overwhelming victory in 1973, Bourassa had become more willing to respond to nationalist demands that he enact language legislation. The following year the Official Language Act, also known as Bill 22, retreated from bilingualism in Quebec. It made French the official language of the province, the government, and its services; expanded the use of French in the workplace; and restricted access to English schools to those children who had a knowledge of the language. It infuriated Trudeau. In a speech in March 1976 he lashed out at Bourassa; the bill was “politically stupid,” the Quebec government’s approach to constitutional revision obtuse, and earlier he had described Bourassa himself as no more than an eater “of hot dogs.” Trudeau’s speech itself seemed politically stupid when, on 15 November, the Parti Québécois under Lévesque trounced Bourassa’s Liberals in the provincial general election. Although Bourassa had called the election to obtain a mandate for constitutional negotiations, Trudeau told Canadians that Quebec had not voted on the constitution but on “economic and administrative issues.” It probably had, but the effect was to create a constitutional crisis because Lévesque was committed to a referendum on “sovereignty-association,” a concept which Trudeau and his colleagues regarded as tantamount to separation but which Lévesque and his followers argued was an economic and political association similar to the emerging European Union. Initially, the Liberals soared in the public opinion polls across the country as the constitution, which had been so important in bringing Trudeau forward, once again became a major issue. In the first two months of 1977 Trudeau proposed discussions that would lead to the repatriation of the constitution and entrenchment of language rights, said he would resign if Quebec voted for independence, and told the American Congress that only “a small minority of the people of Quebec” supported separation. Simultaneously, Quebec politician Camille Laurin, once a friend of Trudeau, prepared the Charter of the French Language. Also known as Bill 101, it went far beyond Bourassa’s legislation in requiring the predominance of French in commerce, business, and communications and in compelling the children of immigrants to Quebec to study in French. It was passed by the province’s National Assembly on 26 Aug. 1977.

In 1978, under their new leader, Charles Joseph (Joe) Clark, chosen in February 1976, the Conservatives began to move up in the polls as public attention turned back to the faltering Canadian economy. Union strife, low productivity increases, and a weak American economy combined to cause a string of budgetary deficits and a declining Canadian dollar. James Allan Coutts, Trudeau’s principal secretary at the time, later remarked that the prime minister became exceedingly flexible and showed himself willing to consider full-scale review of the division of federal and provincial powers. On 5 July 1977 Trudeau established a task force on Canadian unity under the joint chairmanship of Pépin and former Ontario premier John Parmenter Robarts*. It held hearings across the nation throughout 1978 and in January 1979 recommended decentralization and a special status for Quebec. These were not solutions Trudeau wanted.

There would be no further action because the government’s mandate ended in 1979. Trudeau called an election for 22 May 1979 with the Conservatives, buoyed by the results of recent by-elections, slightly ahead in the polls. However, Trudeau was widely perceived to be a better leader. Coutts and Senator Keith Davey therefore decided to capitalize on this perception of the prime minister, making him the “gunslinger” – “standing alone, feet apart, thumbs hooked under his belt, with no podium or speaker’s text, appearing to think on his feet and ready to take on all comers.” The image was symbolic because so many of his strong ministers, such as Turner and Donald Stovel Macdonald, had left; he now was the only “wise man” in the cabinet, Pelletier having become a diplomat and Marchand having gone to the Senate. Trudeau’s own performance on the hustings and in the televised debate was excellent, but Clark had the advantage of novelty and the peculiarities of the Canadian electoral system. Even though the Liberals took just over 4 per cent more of the popular vote, the Conservatives won a greater number of seats. The country was divided regionally. The Liberals, who had done poorly in the west since the 1960s because of the impression that the party’s leaders had concentrated on central Canadian problems such as bilingualism, maintained support in Quebec and much of Ontario but the results elsewhere were disappointing. Of the Liberals’ 114 seats, 67 came from Quebec and only 3 from the west, 2 of them in Manitoba; of the Conservatives’ 136 seats, 57 came from the west and only 2 from Quebec.

In 1978 journalist George Radwanski had published a biography of Trudeau based upon extensive interviews that suggested the prime minister had begun to consider his own place in history. Although Trudeau was not yet a great leader, he concluded, he had “governed intelligently in a difficult time.” He was “not a failed prime minister but an unfulfilled one.” Trudeau probably agreed. He had told the American ambassador, Thomas Ostrom Enders, in August 1976 that his government had not been able to solve the constitutional problem or deal with the “great wastefulness” of the 1970s. Worst of all, it had not vanquished separatism. Enders, one of the finest American ambassadors, shrewdly noted that Trudeau was “convinced of his vision but [was] trying to govern by fiat rather than his very considerable skills as a practical politician.” It had not worked. In early June 1979 Trudeau seemed at ease as he left 24 Sussex Drive in his elegant albeit ancient Mercedes-Benz 300SL and prepared for a life as a single father without the burdens of the prime minister’s office. On 21 November he announced his resignation as leader of the party, telling members of the press that “I’m kind of sorry I won’t have you to kick around any more.” They applauded.

Then, on 13 Dec. 1979, Clark refused to back down when told that the Liberals had the votes in the house to defeat his government on an unpopular budget which had also placed the Conservatives well behind in the polls. The Tory downfall was brilliantly managed by Allan Joseph MacEachen, the leader of the Liberal opposition, who immediately plotted with Coutts, Davey, and Lalonde to assure Trudeau’s return. Trudeau hesitated briefly, but on 18 December he announced that he would lead the Liberals into the election.

During the campaign, Trudeau’s advisers kept him away from the press, which was generally hostile, with the exception of the faithful Toronto Star. Yet the polls remained strong. On 18 Feb. 1980 the Liberals won 147 seats to only 103 for the Conservatives, a solid majority. The NDP had a record 32 seats. The Liberals carried only two seats in the provinces west of the Ontario border, but in Quebec they won an astonishing 74 of the 75 seats and over 68 per cent of the vote there, the greatest win ever in Canadian political history. Towards the end of the 1979 campaign, Trudeau had told a large Toronto rally that he would bring the constitution home even if it meant going over the provincial leaders’ heads and seeking approval through a national referendum. The promise lingered. The Conservatives had shifted to the right during their brief period in office and Liberals recognized that their platform for 1980 should move to the left. With a second energy crisis, created by a revolution in Iran in 1979, redistribution meant taking account of the fiscal imbalances in confederation created by soaring fuel prices.

“Well, welcome to the 1980s!” Trudeau opened his victory address. He ended with American poet Robert Frost’s “But I have promises to keep / And miles to go before I sleep.” The major promise was to find a place for Quebec in Canada and that task was imminent after Lévesque, in December 1979, had set out the conditions for a Quebec referendum on sovereignty-association. The referendum, with an ambiguous question, was scheduled for 20 May 1980. Trudeau’s old rival Ryan, now the Quebec Liberal leader, took charge of the No side and Jean Chrétien, minister of justice and attorney general, represented the federal government in the campaign. The No side initially stumbled badly and Trudeau finally entered the field in early May after polls showed the Yes side pulling ahead. His presence quickly irritated Lévesque, who foolishly said on 8 May that Trudeau had “decided to follow the Anglo-Saxon part of his heritage,” a derogatory reference to the Elliott lineage. Trudeau responded brilliantly in a speech on 14 May declaring that Lévesque had said he “was not as much of a Quebecker as those who are going to vote Yes. That, my dear friends, is what contempt is.” He also made a “most solemn commitment” that if Quebec voted No he would “take action to renew the constitution” after the referendum. With an 85.6 per cent turnout, 59.56 per cent of Quebec’s voters rejected sovereignty-association. It was Trudeau’s greatest victory, but not his last.

Lévesque told voters the night of the referendum that there would be another, a comment that infuriated Trudeau. The next day the prime minister announced to applause from all sides of the House of Commons that he intended to move forward with constitutional changes, among them patriation, an amending formula, and a charter of rights and freedoms. He had a new and dynamic constitutional team, including Pitfield, Lalonde, and Michael J. L. Kirby, which reflected his impatience with the federal government’s conciliatory stance during the late 1970s. At the federal–provincial meeting which took place in September 1980, the premiers were divided among themselves, with most insisting on greater decentralization. Newfoundland premier Alfred Brian Peckford stated that he preferred Lévesque’s vision of Canada to Trudeau’s, which apparently meant that he favoured decentralization to the prime minister’s apparent centralization. Trudeau had hoped for a better provincial response. Shortly after this inconclusive encounter, he met his caucus and asked whether they would go with “the full package” even if the provinces hesitated. They enthusiastically agreed. On 2 October he told the country that because of the premiers’ lack of agreement, he was forced to act unilaterally to patriate the constitution. Canadians needed to assume “responsibility for the preservation of our country.” The great debate that followed split parties: Clark’s Conservatives vigorously fought the plan while Ontario Conservative premier William Grenville Davis and New Brunswick Conservative premier Richard Bennett Hatfield supported it. The federal NDP were not unanimous; four Saskatchewan mps sided with the province’s NDP premier Allan Emrys Blakeney, who opposed it on the traditional British conservative argument that parliament must be supreme in the British system and not limited by the courts.

Provincial governments opposing the plan went to the courts and to the British parliament in London, where approval for patriation was required. In a still-controversial decision rendered on 28 Sept. 1981 the Supreme Court of Canada held that Trudeau’s method of proceeding was legal but unconventional. Both Trudeau and his adversaries claimed victory; the court had forced a compromise. In the meantime, the opposing premiers had formed a “gang of eight” in which Lévesque played a prominent part. They had agreed in April to a plan that permitted patriation and an amending formula involving compensation for provinces that opted out of future amendments. Quebec, in these discussions, did not insist on a veto, an instrument that had created many earlier constitutional quarrels. The federal government rejected this provincial plan; it nevertheless remained alive when the premiers and federal representatives met in November. Trudeau obtained Lévesque’s consent to a national referendum on the constitution, which split the Quebec premier from his allies. Then, in a fateful evening gathering, nine premiers made a deal with Chrétien for patriation. Lévesque was not present; the evening became known as the “night of the long knives,” when the anglophone premiers had figuratively stabbed Lévesque in the back by reaching an agreement without him. Lévesque, the other premiers complained, had broken their alliance and had accepted too quickly Trudeau’s proposed referendum. Bitterness would linger long, but patriation went forward. The Canada Act, 1982, passed by the British parliament, ended that body’s power to amend the British North America Act. It included the Constitution Act, 1982, which contained the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, recognition of the rights of aboriginal peoples, respect for the multicultural heritage of Canadians, a procedure for amending the constitution, and amendments to the BNA Act of 1867. At the insistence of Blakeney, a “notwithstanding” clause that allowed the Canadian parliament or the provincial legislatures to override certain sections of the charter was also incorporated. The clause irritated Trudeau, but it was a small price to pay for the act that was proclaimed by Queen Elizabeth II in Ottawa on 17 April 1982.

Authors Stephen Clarkson and Christina McCall refer to the constitution as Trudeau’s “magnificent obsession.” It remains a remarkable achievement given the forces against change. While none deny the significance of the Canada Act and the charter, many critics in Quebec and elsewhere have claimed that Quebec was “left out,” a criticism that Trudeau firmly rejected. The Quebec referendum and Trudeau’s awareness that the election of 1980 had given him his last chance broke down the high barriers history and personality had erected. The charter would have far more impact on Canadian law and society than even Trudeau had anticipated. To his critics who complained about the treatment of Quebec in the constitutional discussions, he pointed out that Quebec mps had supported the Constitution Act, 1982, and that in June 1982, 49 per cent of Quebecers considered the legislation “a good thing.” His government’s other policies had not fared so successfully, however. A bold attempt by finance minister MacEachen to revise the Canadian taxation system in April 1980 had failed in the face of unrelenting attacks by business and accounting interests. But the major target of the business press and the Conservative opposition was the National Energy Program, which was an ambitious attempt to respond to the rapid rise of energy prices after 1979. It had proposed a “blended” price for oil that would be less than the world price, major incentives for Canadian oil companies to engage in exploration offshore and in the north, and greater state support for Petro-Canada, the federally controlled company despised in Alberta. The government’s ambition was to achieve 50 per cent Canadian ownership of the oil industry by 1990. When introduced in the budget of 1980, the National Energy Program was presented as a means of securing the supply of a scarce resource that all expected would soar in price in succeeding years. In 1982, however, the price of oil began to drop and the National Energy Program fell apart, but not without leaving enduring memories of its confiscatory ways in Alberta and in the Canadian business community.