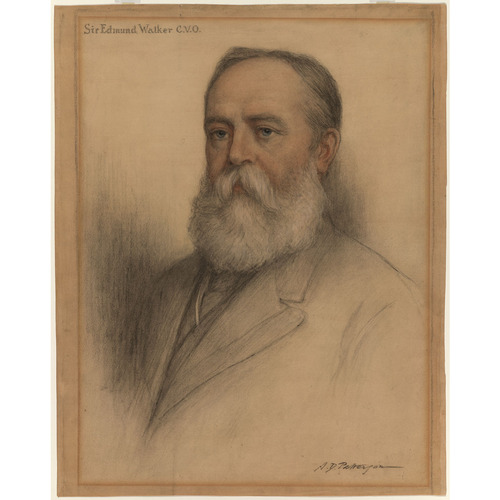

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

WALKER, Sir BYRON EDMUND, banker, philanthropist, and patron of the arts; b. 14 Oct. 1848 near Caledonia, Upper Canada, son of Alfred Edmund Walker and Fanny Murton; m. 5 Nov. 1874 Mary Alexander (d. 1923) in Hamilton, Ont., and they had four sons and three daughters; d. 27 March 1924 in Toronto.

Byron Edmund Walker, born in “the back woods” a half-day’s journey south of Hamilton, became a Canadian Medici and one of the most eminent personalities of his generation. He was the eldest son of an unremarkable family, the second of seven children. He claimed to owe his father “whatever qualities I may possess.” Alfred Walker was the son of middle-class English immigrants who had settled in the Grand River region in the 1830s. Indifferent health made him unsuited to rural life, and in 1852 he, his wife, and their children moved to Hamilton. A clerk, he never distinguished himself in business but he became a noted amateur geologist and palaeontologist. To his son he transmitted his passion for natural history. “I was taught to appreciate that the truth regarding nature was the divine thing,” Walker recalled in 1918, “and that we must learn it so far as it is possible.” There was nothing unusual about their interest in fossils; collecting had become a popular pastime in Victorian Canada. What set young Byron apart was his desire to understand how his discoveries explained the world around him. A lack of formal education never impeded him. He was a dedicated autodidact and his inherited spirit of inquiry led him to master a broad array of subjects. Combined with his organizational acumen, ability to influence, and access to powerful individuals, Walker’s talents served to develop more aspects of Canadian life than those of any of his contemporaries.

It is principally his contribution to commercial life, however, that remains known. One biographer claims that Walker derived his business skills from his mother. Fanny Murton’s parents were also English immigrants of the 1830s, her father, according to Walker’s sister Edith, “a gentleman farmer” who had studied law and her mother an educator who “spoke French and Italian fluently, and was the only woman west of Toronto who could play the harpsichord.” Mrs Murton ran a private school in Hamilton, and it was there that four-year-old Byron began his schooling. He continued at the Central School, finished after grade 6, and at age 12 prepared to enter teachers’ college in Toronto. But doctor’s orders prevented him: “I had better run about, and get a little flesh on my bones” was how Walker remembered the directive. Instead, the boy went to work in August 1861 at the exchange office of his uncle John Walter Murton. The previous winter and spring 11 American states had seceded from the Union. Bonds and paper money issued by the United States government as war measures complicated the already complex North American currency situation. Walker’s duties included the authentication of coins and notes. Pieces of eight, greenbacks, English silver, and the notes of dozens of failed banks: he handled them all. In 1868 he moved to Montreal to run an exchange firm there, but feeble health (which would plague him for another 20 years) forced him back to Hamilton a few months later to work in the local branch of the recently formed Canadian Bank of Commerce.

The bank had been established in 1867 by Irish-born merchant William McMaster* and a consortium of Toronto businessmen in reaction to the growing dominance of the Bank of Montreal [see Edwin Henry King*]. Farmers and businessmen in the province needed greater access to credit, and branches of the Commerce were opened in a number of towns. Walker became a discount clerk in Hamilton. An evaluation from 1869 characterizes him as “an invaluable officer, competent in every respect.” He rose through the ranks swiftly, becoming chief accountant in Toronto in 1872 and junior agent in New York in 1873. Business failures were commonplace during the depressed 1870s, and Walker appears to have been especially skilled at helping his bank minimize its losses. In 1875 he was sent to Windsor, Ont., to disentangle the Commerce from several sour lumber investments. Later he served as manager at the London (1878–79) and Hamilton (1880–81) branches. As inspector at the head office in Toronto from 1879 to 1880, he introduced the use of telegraphy in multiple-branch banking and implemented printed regulations and operating procedures. Subsequently he reorganized the bank into discrete departments, a measure which anticipated modern business practice.

Also during his Toronto stint Walker produced for McMaster (now a senator) and federal opposition leader Edward Blake* a report on how Canadian banking differed from the American system. The government was in the process of reforming the Bank Act of 1871 after a spate of financial woes. A number of banks had failed during the 1870s and critics began to advocate the United States model of more numerous but smaller local banks (though these were frequently undercapitalized) and centralized control of note circulation. Drawing on his New York experience and his training in an exchange office, Walker compared the two systems and favoured Canadian practices. “We have a system which, while it can be improved in some of its details, is fundamentally sound: our bank issues, owing to the strength and peculiar organization of our Banks, pass at par everywhere in the Dominion . . . and the notes are, from the small number of Banks, well known to the most ignorant of tradesmen, mechanics or agriculturists. No practical fault can be found with our Bank-issue as a circulating medium; . . . if it lacks anything in uniform it possesses a much more important virtue in being elastic.” Owing to the structure of Canadian finance, banks were less likely to fail and both borrowers and depositors could be served more securely and conveniently. Partly on the strength of Walker’s report, finance minister Sir Samuel Leonard Tilley* proposed a new general bank act in 1880 which effected only minor changes. The system that had evolved since before confederation remained intact, although decennial revisions of the act meant that the chartered banks regularly had, in Walker’s words, “to fight for our existence.”

His peregrinations continued. In 1881 he began a five-year sojourn in New York, conducting the Commerce’s growing role as a foreign-exchange bank. Walker returned to Toronto in autumn 1886 to become general manager. The previous two years are described in the firm’s official history as “possibly the most difficult” for the bank. It had suffered through customers’ failures in land and timber operations. General manager Walter Nichol Anderson had resigned and Walker was appointed to turn around the company’s fortunes. His first task was a thorough re-evaluation of the bank’s assets and operations. Several changes were necessary, most significantly an adjustment to its deposits-to-capital ratio. The Commerce’s dividends improved markedly as a result, and within ten years Walker had made it the most profitable financial institution in Ontario. Much of this success was due to the program of weekly reports that he implemented in 1889. All branches were required to file a “gossip sheet,” which Walker and his staff used in devising the bank’s plans and objectives. A distillation of these reports was delivered each year in Walker’s address to shareholders. For 35 years financiers and economists in Canada and the United States would benefit from his annual review of the nation’s financial and industrial “pulse.” It was also during his tenure as general manager that the Commerce began to expand its operations westward with branches in Winnipeg, Vancouver, and Dawson, Y.T., for example, and to build up a presence in the Maritimes.

In January 1907 Walker became president of the bank, succeeding Senator George Albertus Cox*. He would hold the office until his death in 1924, although after 1915 he was no longer chief executive officer. His years were ones of tremendous growth: the company’s total assets were $22,000,000 in 1886; by 1915, when John Aird* took the helm, they had increased more than tenfold, as had the number of branches. Walker transformed the bank into a modern corporation with such innovations as a realty company to manage the Commerce’s buildings, a pension fund for retired employees, and a bank archives. After 1915 he continued “to dispense optimism and sober reproof,” guiding junior officers with wisdom earned in nearly a half-century in the bank’s service.

Walker’s high position brought him directly into the exclusive circles of Canadian capitalism. These were interconnected groups of entrepreneurs, bankers, and lawyers who to a great extent had succeeded in concentrating control of the nation’s financial resources. One such group involved railway promoters William Mackenzie and Donald Mann*. Their dream of a northern route to the burgeoning west took them several times to the brink of bankruptcy. Walker was their banker, and he continued to extend credit to them despite worries, widespread among politicians and journalists, that the Canadian Northern’s recklessness would bring it and the Commerce crashing down. His fidelity to the Northern rested on three things: Mackenzie’s friendship, optimism about the potential for profit in the west, and belief in the rightful role of private enterprise to develop Canada clear of government interference. Mackenzie and Mann typified the businessman as nation-builder, and Walker, sharing their vision, gave the bank’s unswerving support, as he did with a variety of other development and utilities schemes at home and abroad.

His reputation in business owed as much to his activities apart from the Commerce. He led the bankers’ section of the Toronto Board of Trade and was instrumental in founding the Canadian Bankers’ Association in 1891 (he would be elected president in 1893 and 1894). His involvement was motivated by his belief that public discourse was too much influenced by journalists who had no expertise in economics. When bank charters were up for renewal in 1890, the newspapers had pressured finance minister George Eulas Foster* to overhaul the current legislation by introducing American-style fixed reserves, a measure favoured as well by Foster’s deputy minister, John Mortimer Courtney*, and by imposing a higher degree of state control over inflation. But Canada’s laissez-faire bankers were hesitant to relinquish any of their privileges. Acting in concert under the leadership of Walker, Edward Seaborne Clouston* (Bank of Montreal), Thomas Fyshe* (Bank of Nova Scotia), and George Hague (Merchants’ Bank of Canada), they were able to preserve their relative independence.

Walker tended to couch his rhetoric in terms of service and development. The branch system, with its handful of chartered banks present from coast to coast, promoted unity and nation-building. Rather than acting out “a compromise between the necessities of the government, arising from war or extravagance, and the commercial requirements of the nation,” Canadian bank policy was the result of a “happier condition where the law-maker and the banker have been mainly concerned to give the people the best instrument in aid of commerce that they could devise.” The Canadian model had served the country relatively well, and was constantly perfecting itself. For as long as Walker remained involved, the banks maintained most of their rights. Where reforms were introduced – for example, the creation of a bank circulation redemption fund, whereby each bank was obliged to deposit with the government an amount equal to five per cent of its average circulation – they were often prompted by his proposals. Only under the strain of war did the state stray from his advice. The Finance Act of 1914 moved Canadian banking away from its laissez-faire origins, a measure which in some ways prefigured the creation of a central bank in 1935.

Walker also enjoyed an international reputation as a banker. “No name is better known among the banking fraternity than yours,” an American colleague told him. In 1913 he was asked to testify before the United States House of Representatives committee on banking, and he frequently addressed foreign audiences on such matters as “Why Canada is against bimetallism,” “Banking as a public service,” “The relations of banking to business enterprise,” and “Abnormal features of American banking.” His knowledge of bank history and his economic theories were promulgated in numerous pamphlets and books, among them A history of banking in Canada. Known as “the pope of the banking system,” Walker often pontificated in defence of financial institutions. “It is the fashion of certain demagogues to speak of bankers and of insurance men as non-producers,” he told the International Convention of Life Underwriters in 1918, “but not even the powers of steam and electricity have done more for industry than credit and insurance.” Credit did more than pave the way to material prosperity; it was an engine of social uplift.

For his many services to Canada, in 1908 Walker had been made a cvo. Two years later King George V knighted him. Although he had been quiet about his politics – “the interests of the Bank are so extensive that I have found it expedient to keep out of politics,” he explained – he had long been a Liberal. In 1911, however, his political aloofness came to an end. The issue was reciprocity, free trade in natural products between Canada and the United States. Canada had prospered under the National Policy of high tariffs on manufactured goods, a creature of Sir John A. Macdonald*’s Conservative government. The Liberal opposition favoured unrestricted reciprocity, but by the time its leader, Wilfrid Laurier*, came to power in 1896, the political and economic usefulness of protectionism had been realized. The Liberal government nevertheless chose to gamble on a policy of free trade in agricultural products, and in January 1911 announced the terms of the Taft-Fielding agreement [see William Stevens Fielding]. Within a month Canadian businessmen had emerged squarely against the deal: free trade in some products now, they argued, meant unrestricted reciprocity later, a break with the British empire, and eventually annexation.

It was in fact the business community, not the ineffectual Conservative opposition, that led the campaign against Laurier. The most highly organized and nationally prominent anti-reciprocity force was the “Toronto Eighteen,” headed by Walker. Described by one historian as “an inter-locking structure of banking, transportation, insurance, manufacturing and other related interests,” they unleashed, in the words of another, “a firestorm of anti-American sentiment.” They helped create such propaganda bodies as the Canadian National League and the Canadian Home Market Association, published anti-free trade tracts, cartoons, and advertisements, and blanketed the nation with pamphlets publicizing their position. In the general election of September 1911 voters defeated the Liberal government. Walker had been invited by Robert Laird Borden*, leader of the opposition, to run as a Conservative but had declined. However, he advised the new prime minister on a variety of issues during his term. Laurier likely never forgave him. A Toronto newspaper was surprised to find the two seated side by side at a University of Toronto gathering in 1914. The banker quipped, “Well, if Sir Wilfrid does not object I see no reason why I should.”

Walker’s opposition to reciprocity stemmed from his views on how best to develop Canada’s economic position. This small nation could either continue to prosper as a dominion within the empire, he believed, or disappear into the United States. He never liked the way the American economy had taken shape. For example, he denounced the overthrow of founding father Alexander Hamilton’s financial system, which he considered sane and intelligent. He also disparaged America’s “gross materialism” and tendency to waste. His anti-free trade protest was, therefore, based on “much more than a trade question. . . . The question is between British connection and what has been well called Continentalism.” The extent of his anti-Americanism, however, is open to argument. He would tell Canadian audiences they should “save and increase such good qualities as tend to differentiate us from the United States,” among them a disdain for “extreme democracy” and suspicion of industrial oligarchy and “machine politics.” On the other hand, he told Americans that, while he disliked some features of their country, he greatly admired others. He simply valued Canada’s ties to Britain much more and did not think they could be maintained if America’s influence grew too strong. Walker was an imperialist, with James Mavor, Edward Joseph Kylie* and George MacKinnon Wrong* a member of the Round Table movement, and a believer in the empire as “the greatest political and social enterprise in the history of the world.”

It has been suggested that Walker’s fight against reciprocity was in part motivated by anti-immigrant sentiment. He was not a hateful man, no more so than any of his contemporaries. He was “proud to feel that Canada was a place where every color and every kind could have an opportunity,” but objected to immigrants’ seeming hesitance to integrate with British Canadian society. He blamed agricultural settlers in the west for Laurier’s departure from protectionism. Immigration itself was not a menace; in fact, Walker understood it to be the catalyst to the economic boom of the century’s first decade. Yet he was concerned that Canada had taken in more foreigners than it could absorb. Without proper measures, they could threaten law and order, and indeed seemed to be weakening the imperial tie.

Walker frequently spoke of particular “Canadian ambitions” and felt that these should be inculcated in newcomers. The alternative was to become too much like the materialistic, polyglot, and potentially unstable United States. “No great nation,” he remarked in 1907, “was ever built up solely on the basis of material prosperity,” and he insisted that Canadians strive for something greater. This ideal could be attained by cultivating proper tastes and sensibilities and would be aided principally by two things: higher education and the fine arts. To these ends, Walker promoted a wide array of institutions, first among them schools “where the duties of citizenship and the ethical aspects of life are taught in the fullest manner.” He was a Toronto Board of Education trustee in 1904, and in 1911 founded the Appleby School in Oakville, Ont.

The University of Toronto benefited most from his efforts. After his return from New York to stay, his family had acquired Long Garth, a large home literally in the university’s backyard. In 1890 fire destroyed a good part of the main college building. In addition to witnessing the blaze, Walker was asked by President Sir Daniel Wilson* to head the campaign to raise funds for restoration. His bank donated $1,000 and many local and national businesses followed the example. Subsequently Chancellor Edward Blake asked him to supervise the university’s financial situation, and later he worked with Joseph Wesley Flavelle* on the royal commission on the University of Toronto (1905–6), which suggested major changes to funding and management. Shortly before it federated with the university in 1904, Trinity College had made him an honorary dcl and in 1905 the university itself granted him an honorary lld. He served the university as a trustee (1891–1906), senator (1893–1901), governor (1906–23), and chairman of the board of governors (1910–23), and assumed the office of chancellor upon Sir William Ralph Meredith’s death in 1923. Walker considered the university to be “the most important institution in Canada apart from the Government itself.” In 1918 the minister of education, Henry John Cody*, elaborated on Walker’s views: “He believed in the value and power of education in the whole life of the Province and Dominion. Education is at once the key to efficiency and the safeguard of democracy. . . . The universities . . . can render an incalculable service both to the higher life of our people and to the commercial and manufacturing interests of the country.”

Among its many recommendations the Flavelle report had proposed a museum for the university. Walker had been advocating such an institution since 1888 when he approached the premier, Oliver Mowat*. He believed that museums afforded the public an opportunity to appreciate the country and the world around them. They would be “shop windows” in which newcomers and Canadians of long standing could understand, at a single glance, the nation’s potential. But only in 1909 did the government consent to funding, and not before Walker and Edmund Boyd Osler had independently raised some money to establish the Royal Ontario Museum. Five years before, Walker had donated his library and his collection of fossils to set the organization in motion.

During their New York years, Walker and his wife had had a rich social life, complete with visits to museums, concert halls, and libraries where they cultivated a love of literature. Their return to Toronto in 1886, therefore, came as a disappointment. The Queen City was growing but it had none of the cultural life of other centres. Nonetheless, its artists and business class aspired to such development. What mainly lacked was leadership. Walker was able to provide the missing element and was unmatched in the range of his accomplishments. For example, local artists had for many years sought an art museum. Painter George Agnew Reid*, president of the Ontario Society of Artists, had been unable to establish a permanent one, but in 1900 Walker joined the cause, raised money privately, set up a board of trustees, and arranged with Harriet Elizabeth Mann Smith and Goldwin Smith* to have their house, the Grange, bequeathed to the Art Museum of Toronto. The Toronto Guild of Civic Art, which adjudicated public art and urban planning schemes, also benefited from his participation.

Walker’s involvement in art was more than organizational. He was also a collector, and though his holdings were not as extensive as some, he had extraordinary access to important private collections abroad and knew many artists personally. He advised his friends on building private galleries, and as a result many Canadian collections came to reflect his preference for Dutch interiors and the Barbizon School. He was fondest of Italian art and in 1894 lectured about it at the University of Toronto. In his later years he developed an exquisite collection of Japanese prints (now in the Royal Ontario Museum). His taste in art was cultivated by extensive reading and travelling. He journeyed throughout Europe, spent long periods in England, and visited South America and the Far East.

His cultural activities also took place at the national level. He felt his most important contribution to Canada was the founding in 1905, with historian George M. Wrong and librarian James Bain*, of the Champlain Society, an organization which publishes historical documents. His interest in history also led him to serve the National Battlefields Commission, the Quebec tercentenary committee, and the Historical Manuscripts Commission. During the 1914–18 war Lord Beaverbrook [Aitken*] sought his advice on developing the Canadian War Memorials Fund, and Walker successfully suggested that Canadian artists be commissioned to paint war scenes.

Walker was embroiled in a number of controversies concerning art. One stemmed from his involvement with the National Gallery of Canada. The Royal Canadian Academy of Arts had helped found the gallery in 1880. However, after a quarter-century it was still little more than a repository of diploma works. Artists lobbied for a more complete institution, and in 1907 the government appointed the Advisory Arts Council [see Sydney Arthur Fisher]. Walker became its head in 1910 and in 1913 chairman of the reincorporated National Gallery’s board of trustees. Among other tasks he and his colleagues were instructed to build up the national collection. None was an artist, and all came in for criticism, especially Walker because of his very definite likes and dislikes. The most public conflict took place in 1923 when the RCA took strong exception to the National Gallery’s selection of a jury which would choose works of art to represent Canada at the British Empire Exhibition. Critic Hector Willoughby Charlesworth* agreed and argued that Walker and gallery director Eric Brown* were wrong to show favouritism to Canadian painters whose work he considered “labored, dull, and unimaginative.” Charlesworth called the gallery a “national reproach,” echoing mp Charles Murphy* who in 1921 had labelled it “a haven for the special pets of Sir Byron Walker.” Despite the criticism, Walker had built a permanent foundation for the gallery, had seen that it survived the war years, and had helped secure relatively generous public funding. Indeed, his death was seen as a loss to the arts in Canada. Walker himself recognized the progress his generation of patrons facilitated: young Canadian painters had begun to “paint our country in moods, colours and atmosphere which cannot be mistaken for anything but Canada”; in a short period, he said in 1923, aesthetic standards had increased to the point that Canada had become much “nearer to the great centres of the world.”

Music also benefited from Walker’s dedication and acumen. He worked with the Toronto Conservatory of Music and its director, Augustus Stephen Vogt, and arranged the school’s affiliation with the university. Particular pleasure he derived from his involvement in the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir, founded by Vogt, which he helped reorganize in 1900. He secured funding for the group and was named its honorary president. He enjoyed travelling with the choir, and in early 1924 was on tour with them in the United States when he contracted pneumonia. Minnie, his wife of nearly 50 years, had just died and Walker coped with his grief by burying himself in his projects. He had begun to work long nights settling the estate of his friend Sir William Mackenzie, and was about to leave for England to attend the British Empire Exhibition when he expired.

Walker admonished students to avoid committing “the historical estimate.” He said they should not hold a person in high regard simply “because he accomplished work important for his time”; however, someone whose deeds were “important for all time” was to be valued. Certain of his contemporaries considered Walker to be too powerful and overextended into areas they said he knew little about. He was sometimes seen as “arrogant, domineering, and pretentious.” But Walker simply trusted his own judgement and ability. Furthermore, he “had an extraordinary power of creating enthusiasm.” In retrospect, the worst his enemies could say about him was that he was “a strong man with a liking for his own way of doing things.” “Remember each day,” he told the Schoolmen’s Club, “that we shall be judged by our children according to the use we have made of the really vast opportunity which fortune has placed in our hands.” Clearly he accomplished much, in many fields, at several levels, and in lasting ways.

[Many of Walker’s addresses were published in professional journals or as pamphlets. A good sampler is Addresses delivered by Sir Edmund Walker, c.v.o., l.l.d., d.c.l., during the war ([Toronto, 1919]). A history of banking in Canada was originally presented to the Congress of Bankers and Financiers at Chicago on 23 June 1893, and appeared in the Canadian Bankers’ Association Journal (Toronto), 1 (1893–94): 1–25, under the title “Banking in Canada.” The History went through numerous reissues and revisions, including the Toronto editions of 1899 and 1909. Walker’s contribution to the Dictionary of political economy . . . , ed. R. H. I. Palgrave (3v., London and New York, 1894–99), on “Canadian banking” also appeared in pamphlet form at Toronto sometime in the 1890s. The majority of Walker’s publications have been made available on microfiche by the CIHM and are listed in its Reg. A chronological listing of Walker’s addresses and publications is available in box 34A, file 3, of his papers at the Univ. of Toronto, infra. Also listed in both sources is a pamphlet issued by the Canadian Bank of Commerce under the title Jubilee of Sir Edmund Walker, c.v.o., l.l.d., d.c.l., 1868–1918 (Toronto, 1918), to commemmorate his 50th year of service.

The principal repository of manuscript documents is the Walker papers at the Univ. of Toronto Library, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library (ms coll. 1). The records of the Civic Guild of Toronto (formerly the Toronto Guild of Civic Art) are preserved in TRL, SC. Walker’s involvement in the fine arts is documented in archival collections in the library of the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, and in the B. E. Walker papers and Advisory Arts Council records in the National Gallery of Canada Library, Ottawa. Finally, both the CIBC [Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce] and the Canadian Bankers’ Association possess institutional archives in their head offices in Toronto.

There are three biographies: George P. de T. Glazebrook’s commissioned study, Sir Edmund Walker (London, 1933); C. W. Colby, “Sir Edmund Walker,” Canadian Banker (Toronto), 56 (1949): 93–101; and B. R. Marshall, “Sir Edmund Walker, servant of Canada” (ma thesis, Univ. of B.C., Vancouver, 1971). Marshall’s dissertation is very good, but is not widely available. Hector Willoughby Charlesworth writes about Walker in More candid chronicles: further leaves from the note book of a Canadian journalist (Toronto, 1928), as does Augustus Bridle in Sons of Canada: short studies of characteristic Canadians (Toronto, 1916). The business side of his life can be culled from Victor Ross and A. St L. Trigge, A history of the Canadian Bank of Commerce, with an account of the other banks which now form part of its organization (3v., Toronto, 1920–34); R. T. Naylor, The history of Canadian business (2v., Toronto, 1975); and Christopher Armstrong and H. V. Nelles, Southern exposure: Canadian promoters in Latin America and the Caribbean, 1896–1930 (Toronto, 1988). On Walker’s involvement in politics and public life, see the Canadian annual rev., 1901–24, and R. D. Cuff, “The Toronto Eighteen and the election of 1911,” OH, 57 (1965): 169–80, as well as A. B. McKillop, Matters of mind: the university in Ontario, 1791–1951 (Toronto, 1994).

K. A. Jordan, Sir Edmund Walker, print collector: a tribute to Sir Edmund Walker on the seventy-fifth anniversary of the founding of the Art Gallery of Ontario (exhibition catalogue, Art Gallery of Ontario, 1974), and Images of eighteenth-century Japan: ukiyoe prints from the Sir Edmund Walker collection, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, comp. David Waterhouse ([Toronto], 1975), discuss Walker the art connoisseur. Maria Tippett, Art at the service of war: Canada, art and the Great War (Toronto, 1984) and Making culture: English-Canadian institutions and the arts before the Massey commission (Toronto, 1990), Lovat Dickson, The museum makers: the story of the Royal Ontario Museum (Toronto, 1986), and David Kimmel, “Toronto gets a gallery: the origins and development of the city’s permanent public art museum,” OH, 84 (1992): 195–210, survey some of his organizational contributions to Canadian cultural life. The best discussion of Walker’s confrontations with critics is found in Ann Davis, “The Wembley controversy in Canadian art,” CHR, 44 (1973): 48–74. d.k.]

Cite This Article

David Kimmel, “WALKER, Sir BYRON EDMUND,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/walker_byron_edmund_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/walker_byron_edmund_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | David Kimmel |

| Title of Article: | WALKER, Sir BYRON EDMUND |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | January 20, 2025 |