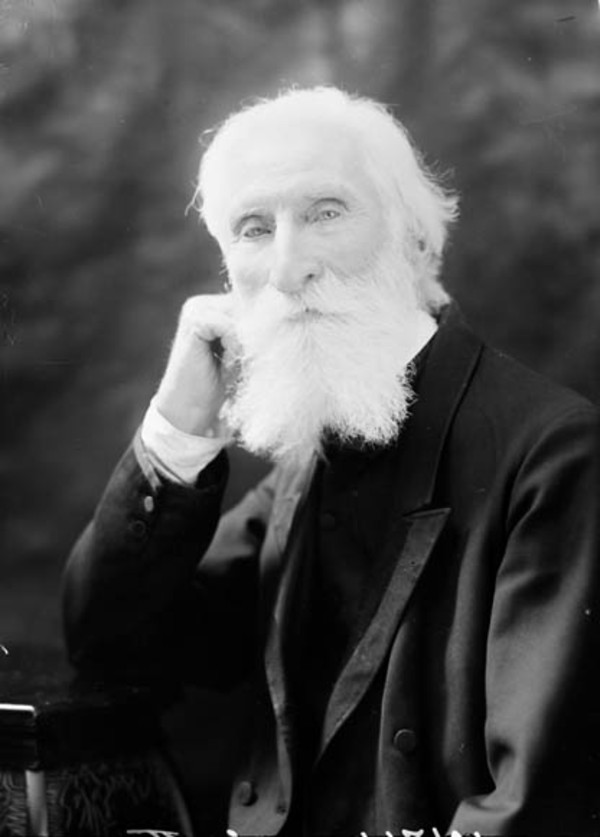

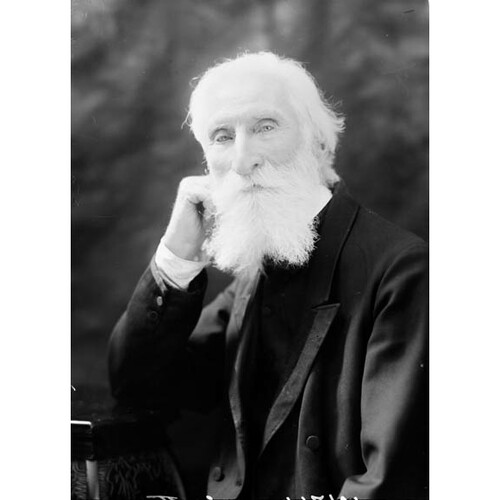

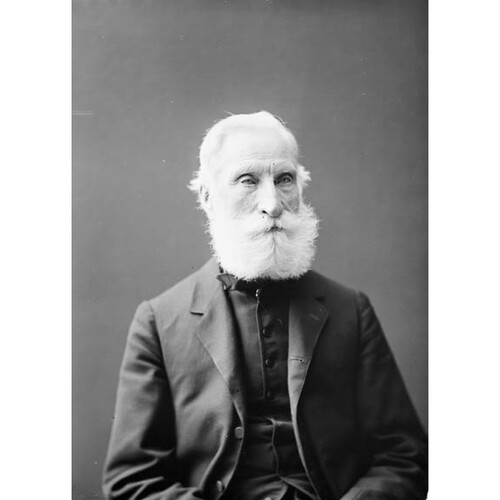

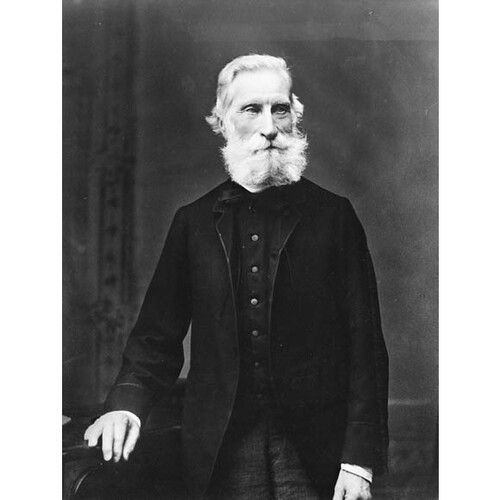

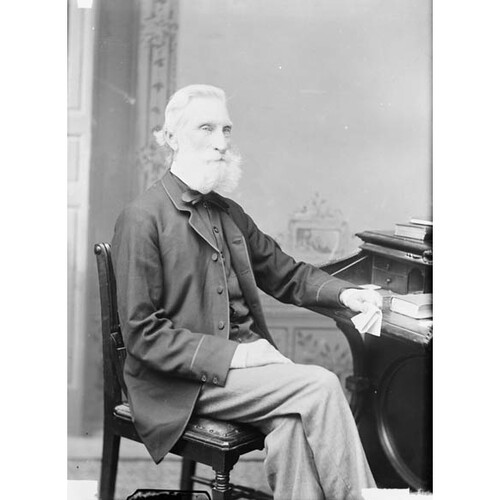

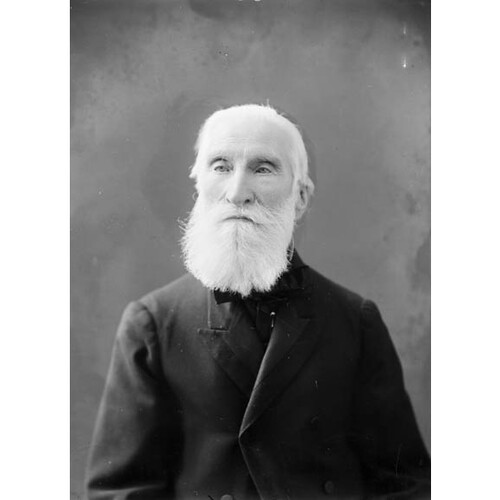

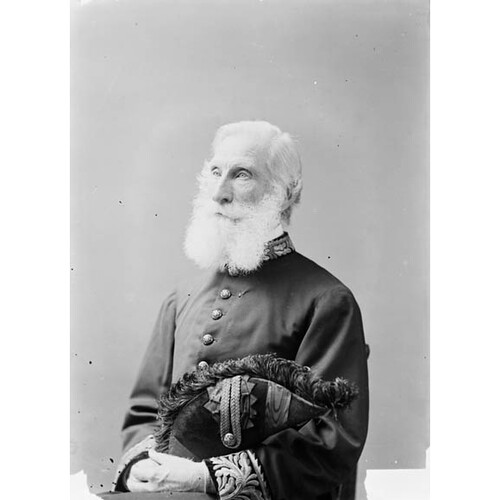

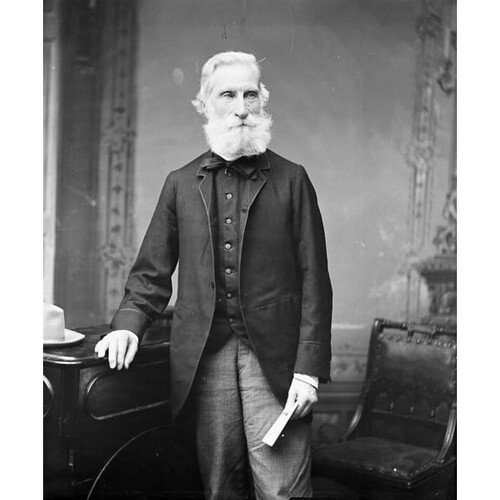

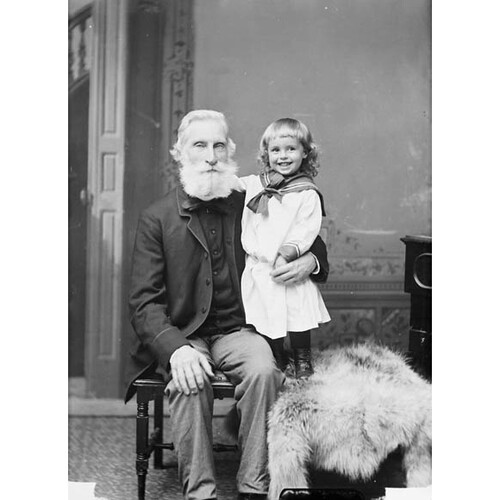

SCOTT, Sir RICHARD WILLIAM, lawyer and politician; b. 24 Feb. 1825 in Prescott, Upper Canada, son of William James Scott and Sarah Ann McDonell; m. 8 Nov. 1853 Mary Ann Heron (d. 1905) in Philadelphia, and they had three sons and five daughters (a son and a daughter died in infancy); d. 23 April 1913 in Ottawa.

William James Scott, a descendant of a family from County Clare (Republic of Ireland), served as a hospital mate in the Peninsular War before coming to Quebec with the British army in 1814. He married a daughter of Captain Allan McDonell (Leek), a loyalist settler in Matilda Township, Upper Canada, and in 1824 located in Prescott, where he developed a “large but unremunerative” medical practice. Raised as a Catholic and educated at home, Richard started his apprenticeship in law at age 18. After being admitted to the bar in 1848, he established a practice in Bytown (Ottawa), where he would also engage in real estate and sawmilling. He soon entered municipal politics, serving first as a councillor (1851) and then as mayor (1852). As his political career gathered momentum, he fell in love with Mary Heron, an accomplished, Irish-born singer who visited Bytown in 1851 to put on a series of concerts with her family. Scott persisted in courting her and they married in 1853.

In the provincial election of 1854 Scott entered the contest in Bytown as one of three Reform candidates but withdrew when he could not secure party support. He did win in the election of 1857–58, this time pledging himself to the Liberal-Conservative government of George-Étienne Cartier* and John A. Macdonald*. Scott vigorously supported the selection of Ottawa as the capital of Canada, and by the 1860s the Scotts were among the leading Irish Catholic families there. In 1860, after consulting with the Catholic hierarchy, Scott introduced a private bill to amend Upper Canada’s separate school legislation. This bill and its successor the following year both failed to secure second reading because the government wanted to avoid antagonizing Protestant opinion in Upper Canada.

When the 7th Legislature opened in 1862, Scott tabled another bill to extend and codify the rights of separate schools. Promising that it would represent a final settlement of Catholic grievances, he agreed to having it amended in committee and its provisions cleared by Egerton Ryerson*, the chief superintendent of education for Upper Canada, and by the Catholic hierarchy’s representatives, vicars general Angus MacDonell of Kingston and Charles-Félix Cazeau* of Quebec City. After the coalition headed by John Sandfield Macdonald* and Louis-Victor Sicotte* came into office in May 1862, Scott withdrew the bill when it became apparent that his Upper Canadian opponents were prepared to prolong debate indefinitely. Not one to be deterred, Scott reintroduced the bill in March 1863. This time it went through in days, in the absence of many Upper Canadian mlas and on the strength of Catholic votes from Lower Canada. Upon taking office the ministry had committed itself to the principle of “double majority,” whereby each section of the united Canadas was to approve those legislative measures affecting it. Scott’s bill, which would form the constitutional basis for Ontario’s separate school system after confederation, tested this principle and now it lay in tatters. The act itself was a mixed blessing for Roman Catholics. It made it easier for them to form their own school boards, especially in rural areas where they could establish consolidated schools, and to direct their local rates toward separate schools. As well, the act entitled separate schools to share in municipal grants in addition to the provincial grants they had been receiving. In return for these concessions, the schools were to be inspected by the Department of Public Instruction for Upper Canada, which now assumed control over curriculum and teacher training.

Even by the standards of the day, the religious passions unleashed in Upper Canada during the election of June-July 1863 were particularly bitter. Protestant opposition to separate schools ran high and a wave of anti-Catholic sentiment swept through many constituencies, including Ottawa, where Scott was tossed out in favour of Joseph Merrill Currier*. “I don’t think I got twenty Protestant votes,” Scott complained to John A. Macdonald. Though stung by this defeat and hurt even more that his party leaders had deserted him in mid campaign, he bounced back. In 1867, following his appointment as a qc (26 June) and the start of confederation, he won comfortably over Henry James Friel* for the Ottawa seat in the Ontario legislature.

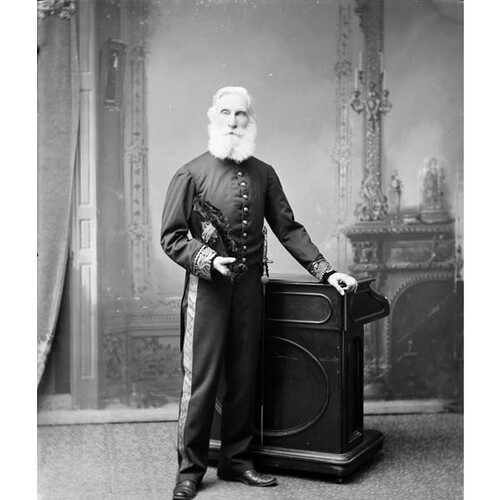

Scott was returned in the election of March 1871 but by then he had distanced himself from Sandfield Macdonald’s coalition. Uneasy that recent educational reforms and legislation pushed by Ryerson could harm separate schools, he was also bitter that the government had not supported the railway and lumbering interests he represented. Appointing Scott speaker of the assembly was one way to mollify and silence him, and at the same time build up good will among Irish Catholic electors. He assumed the speakership on 7 December but would not remain long in the chair.

Macdonald resigned on the 19th and, as soon as Liberal leader Edward Blake assumed office, he offered Scott a position in cabinet. Macdonald accused Scott of “having turned turtle,” but for some time Scott had been one of his more outspoken critics and Blake’s offer gave him the chance to make a clean break. Friends and advisers, but not his wife, urged him to accept, and on 21 Dec. 1871 he became commissioner of crown lands, in which post Scott generated some controversy. His authorization of the rapid sale of northern timberlands on an unprecedented scale provoked charges in 1873 that he had acted as the agent of the lumber interests.

When Alexander Mackenzie* formed a government in Ottawa in November 1873, following the Pacific Scandal, he called Scott to be the Irish Catholic representative in his cabinet, as a minister without portfolio. Scott resigned that month from the Ontario cabinet and legislature to assume this position; on 9 Jan. 1874, just days after a general election was called, Mackenzie appointed him secretary of state. Following a Liberal victory and the opening of parliament, Scott was also named to the Senate, on 13 March.

During the Mackenzie government’s term in office, Scott often filled in for absent ministers: at one time or another he was in charge of Finance, Inland Revenue, Justice, Indian Affairs, and the Interior. His main responsibility, however, was to guide legislation through the Senate. Among the more controversial measures was the North-West Territories Bill of 1875. When it reached the Senate, its separate school clauses provoked sharp criticism that crossed party lines. Leading the defence, Scott argued that peace in the territories depended on recognizing the rights of Catholics, who made up nearly half the population, and the bill squeaked through. Though he would grow into his role in the upper house, Scott could at times add to the prime minister’s load. Following complex negotiations with British Columbia, he seriously mishandled the Esquimalt-Nanaimo Railway Bill in 1875, and in 1877 Mackenzie confessed that “he often blunders in the Senate in spite of all my posting of him daily.”

Scott was honoured by Ontario’s English-speaking Catholics as the champion of their educational rights, but on the national stage his most famous legislative accomplishment was the Canada Temperance Act of 1878. Based in part on the work of a select committee chaired by George William Ross, which reported in 1874, it revised and extended to all of Canada the provisions of Christopher Dunkin*’s prohibition act of 1864. Under the Scott Act, as it became known, a petition by a quarter of the electors in a municipality or county would trigger a local vote to ban the sale of alcoholic beverages. A long-time teetotaller, Scott argued in the Senate that such legislation was necessary “to put down vice and crime.”

Many Liberal supporters in the Maritimes, Ontario, and the west were strong proponents of prohibition, but both Scott and Mackenzie were aware that nation-wide prohibition was hardly a popular measure. Local option enabled the Liberals to please the prohibitionists without driving away those voters who enjoyed a drink, as the Conservatives, who let the bill pass through both houses without a division, well recognized. The political utility of the act then was probably as great as its prohibitionary impact. Its passage galvanized the recently formed Woman’s Christian Temperance Union to campaign for local prohibition [see Letitia Creighton*], but the act’s long-term consequences were another matter. Whether owing to the act or to provincial efforts, the consumption of spirits and wine fell between 1871 and 1893 while that of beer more than doubled.

After the defeat of the Mackenzie government in 1878, Scott led the Liberal opposition in the Senate and he continued to gain recognition. In 1879 he was elected a member of the Dominion Law Society – he maintained a law practice in Ottawa throughout his political career there – and in 1889 he received an lld from the University of Ottawa. Politically, from the late 1880s, he acted as the main channel between the new Liberal leader, Wilfrid Laurier, and the English-speaking members of Ontario’s Catholic hierarchy. This linkage was particularly evident during the Manitoba school debate of the 1890s. Favouring conciliation, Laurier criticized the federal government’s remedial order of 1895 that required the government of Thomas Greenway* to restore Catholic schooling in Manitoba. Explaining his leader’s position to Archbishop John Walsh* of Toronto in February 1896, Scott argued that the recently introduced remedial bill would provoke the hostility of Manitoba’s Protestant majority and in the long run injure “the cause of the minority.” In private he feared the Conservatives’ remedial policy would draw Catholic support, but in June Laurier and the Liberals swept to power.

Scott pressed his claims for a position in cabinet, reminding his chief that, after being Senate leader for 18 years, “it would be rather humiliating” not to be included. His plea, which was likely motivated in part by a need for more income to support his family, met with only partial success. Though he was reappointed secretary of state in July, the leadership in the Senate was assumed by justice minister Sir Oliver Mowat*. For Laurier, placing Scott in the cabinet, over the known opposition of some Ontario Liberals, was one means of securing favour among the English-speaking Catholic hierarchy. Seemingly addicted to work and a master on Parliament Hill, Scott also remained one of Laurier’s most trusted senior colleagues. During the summer of 1897, while the prime minister was in England, he joined Mowat, interior minister Clifford Sifton*, and solicitor general Charles Fitzpatrick* in discussions with Manitoba. These paved the way for the agreement in November that resolved the school question by providing for religious instruction in schools and instruction in French and other languages. Like many other advocates of Irish Home Rule, Scott vigorously advocated Canadian autonomy, for which he suspected the British government and its officials had scant regard. Despite periodic clashes with Governor General Lord Minto [Elliot] and imperial officers in Canada, as well as his initial opposition in 1899 to the dispatch of Canadian troops to the South African War (he felt there was an imperial conspiracy of coercion), Scott served as acting prime minister on several occasions.

In 1905, when the government introduced legislation to create the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan, which would have brought Catholic education under the protection of section 93 of the British North America Act, controversy again erupted over separate schools. Although Scott preferred the government’s initial proposals, to preserve the dual system of education as set out in the North-West Territories Act of 1875, he recognized that it was headed for electoral disaster if it insisted on pushing the legislation. He therefore accepted the course finally adopted by Laurier: to enshrine the territories’ educational ordinances of 1901. Although these ordinances established a uniform curriculum for publicly supported schools, they at least permitted religious instruction at the end of the school day.

Always at his post, Scott never took a holiday until he had reached the advanced age of 81, maintaining that work was his “chief recreation.” During the summer months, when cabinet colleagues were off, Scott would keep Laurier up to date on business while the prime minister was at home in Arthabaskaville (Arthabaska), Que. In 1902 Laurier appointed him Senate leader. Six years later Scott, feeling that he could no longer keep up his hectic pace of administration, resigned from cabinet and as leader in the Senate, which he would assiduously continue to attend. Created a knight bachelor in 1909 in recognition of his services, he keenly followed developments in those public sectors that had once preoccupied him. In 1912, for instance, in the wake of Regulation 17 in Ontario’s educational system [see Sir James Pliny Whitney], he spoke out once again in defence of separate schools and French language rights. That same year his son William Louis* became president of the newly formed Association of Children’s Aid Societies. In 1907 Scott had supported his son’s efforts for reform by introducing the Juvenile Delinquents Bill in the Senate.

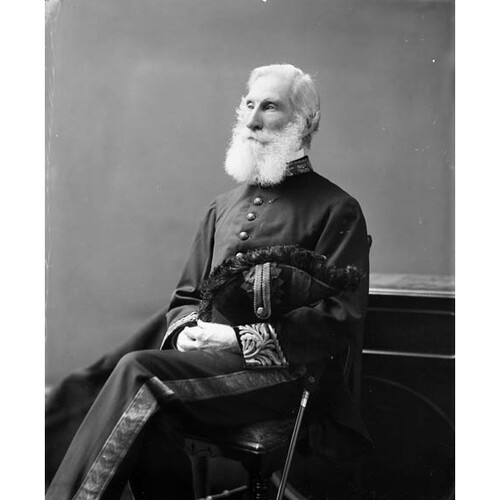

Although Scott was a dedicated teetotaller and vegetarian from his youth, he and his wife entertained on a lavish scale and their wine cellar was always amply stocked. A man of decided opinions, he took pride in his independence of mind, and as he aged he displayed some irascibility. At home he nevertheless continued to preside over a “rollicking noisy clan.” A strong believer in the virtues of clean living and exercise, he favoured hydropathy over drugs and doctors. Until his last days he struck everyone as the picture of health; photographs portray him as a fit-looking man with a patriarchal beard. He addressed the Senate on 26 Feb. 1913 on limiting appeals to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council and spoke for the last time on 7 March; in April, following prostate surgery, he died at his home on Daly Avenue surrounded by family. Archbishop Charles-Hugues Gauthier* had performed the last rites, and Scott was buried in Notre-Dame Cemetery in Ottawa. His funeral cortège, which the Ottawa Citizen estimated was three-quarters of a mile long, included many of the leading political figures of the day as well as the entire staff of the Senate.

Scott’s publications include Synopsis of the Manitoba school case, with appendix of explanatory documents (Ottawa, 1897); “Establishment and growth of the separate school system in Ontario,” in Canada, an encyclopædia (Hopkins), 3: 180–87; The choice of the capital; reminiscences revived on the fiftieth anniversary of the selection of Ottawa as the capital of Canada by her late majesty (Ottawa, 1907); and Recollections of Bytown: some incidents in the history of Ottawa (Ottawa, [1911]). His speeches on Catholic educational rights were printed along with those of Thomas-Alfred Bernier* as Speeches of Hon. Messrs. Bernier and Scott on the Manitoba and N.-W. school question (n.p., [1894?]). Scott is also the author of a privately issued memoir, Some incidents in the public life of Hon. R. W. Scott (n.p., [1908]); a copy is preserved among the Alexander Fraser of Fraserfield papers at AO, F 558, ser. V-3.

AO, F 558, ser.V-2; RG 22-354, no.6878; RG 80-8-0-302, no.7651; RG 80-8-0-487, no.10844. NA, MG 26, G; MG 27, II, D14; MG 30, C27, 23. Private arch., D. W. Scott (Ottawa), Scott family papers. Globe, 1860–63, 1908–13. Ottawa Citizen, 1852–1913, esp. 19 Nov. 1853. Packet (Bytown [Ottawa]), 1850–51. Can., Prov. of, Legislative Assembly, Journals, 1856–64. Can., Senate, Debates, 1873–1913. Canadian annual rev. (Hopkins), 1909–12. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). CPG, 1877. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.2. Sandra Gwyn, The private capital: ambition and love in the age of Macdonald and Laurier (Toronto, 1984). D. B. Knight, A capital for Canada: conflict and compromise in the nineteenth century (Chicago, 1977), 212, 220–27. R. S. Lambert with Paul Pross, Renewing nature’s wealth: a centennial history of the public management of lands, forests & wildlife in Ontario, 1763–1967 ([Toronto], 1967). Lord Minto’s Canadian papers: a selection of the public and private papers of the fourth Earl of Minto, 1898–1904, ed. and intro. Paul Stevens and J. T. Saywell (2v., Toronto, 1981–83). Carman Miller, Painting the map red: Canada and the South African War, 1899–1902 (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1993). J. S. Moir, Church and state in Canada West: three studies in the relation of denominationalism and nationalism, 1841–1867 (Toronto, 1959). Newspaper reference book. W. L. Scott, “Sir Richard Scott, k.c. (1825–1913),” CCHA, Report, 4 (1936–37): 46–71. Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell). D. C. Thomson, Alexander Mackenzie, Clear Grit (Toronto, 1960). Types of Canadian women . . . , ed. H. J. Morgan (Toronto, 1903). F. A. Walker, Catholic education and politics in Ontario . . . (3v., Toronto, 1955–87; vols.1–2 repr. 1976), 1.

Cite This Article

Brian P. Clarke, “SCOTT, Sir RICHARD WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 20, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/scott_richard_william_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/scott_richard_william_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Brian P. Clarke |

| Title of Article: | SCOTT, Sir RICHARD WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | December 20, 2024 |