Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

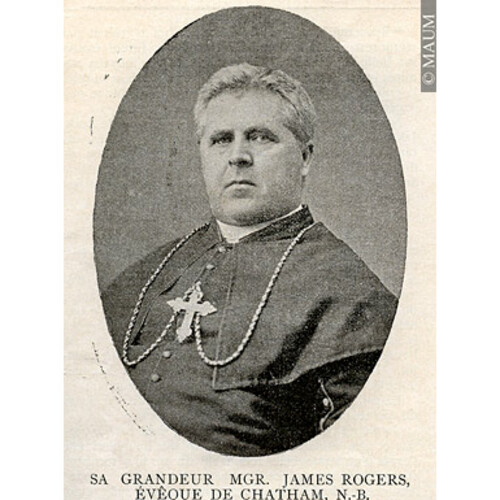

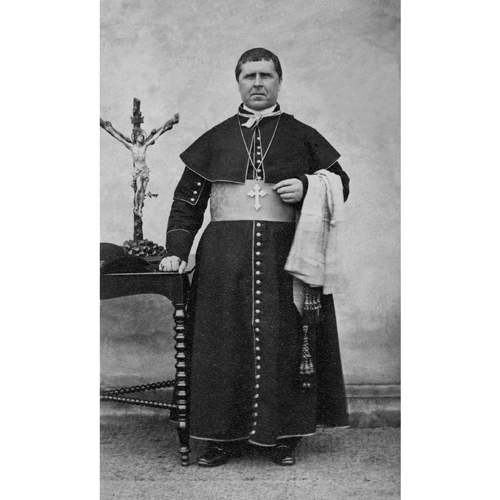

ROGERS, JAMES, Roman Catholic priest and bishop; b. 11 July 1826 in Mountcharles (Republic of Ireland), only son of John Rogers and Mary Britton; d. 22 March 1903 in Chatham, N.B.

In 1831 the young James Rogers and his parents immigrated to British North America. The family settled in Wallace, N.S., but soon relocated in Halifax, where they experienced hardship and poverty. Owing to his father’s ill health, James became the family’s breadwinner during his teenage years. At an early age he demonstrated a remarkable maturity and holy demeanour, and contemplated the priesthood as a vocation.

In 1847, after the death of his father, Rogers entered St Mary’s College, Halifax, where he received a classical education and became the protégé of his confessor and professor of theology, Thomas Louis Connolly*. Following his ordination as subdeacon in August 1850, Rogers, with the financial sponsorship of Bishop William Walsh*, continued his studies at the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice in Montreal, where he resolved to acquire a fluency in French. On 2 July 1851 he was ordained at St Mary’s Cathedral in Halifax. The young priest was immediately dispatched as missionary rector to western Nova Scotia, where he manned an extensive mission field centred on Church Point, diligently fortifying the Catholic presence by preaching in English, French, and occasionally Micmac. His exertions showed no lack of nerve, apostolic enthusiasm, or good-natured humour. In 1853 Rogers was assigned to Cumberland County and the neighbouring regions of Colchester County. This posting proved rigorous and in 1856, on his recommendation, the mission was divided, to reflect the ethnic duality of its Acadian and anglophone constituents. Amherst then replaced Minudie as the centre of Rogers’s activities.

In 1857 Rogers was called to a remote corner of the archdiocese of Halifax – Bermuda. There he ministered to convicts and other “struggling members of the Fold” and was an important catalyst in the construction of the island’s first Catholic church. After returning to Nova Scotia in April 1859, he served briefly as pastor at Church Point, but was summoned that summer to Halifax to act as secretary to Connolly, now archbishop, and to assume a professorship at St Mary’s College.

Another promotion soon followed. On 8 May 1860 Rogers was appointed first bishop of the newly established diocese of Chatham, which comprised the northern half of New Brunswick. Only 33, he had been selected over more senior priests, and even he was dismayed by the “unexpected” appointment, which no doubt owed something to the influence of friends such as Connolly and Bishop John Sweeny of Saint John. However, the choice was not ill considered. Rogers was no stranger to poverty and rural simplicity and possessed abundant reserves of sacerdotal stamina and zeal. In a sparsely inhabited and impoverished diocese these qualities would be required in large supply.

On 15 Aug. 1860 Rogers was consecrated in Charlottetown. He was installed in St Michael’s Pro-Cathedral, Chatham, seven days later. He immediately plunged into a crowded schedule of pastoral visitations, confirmations, sick-calls, confessions, and adjudications. Many of these activities, he conceded, more befitted “a general missionary” than a “stationary bishop.” But meagre resources demanded adjustments. In 1860 the diocese, later described by Rogers as “one of the poorest in all America,” had only 7 priests, and 30 churches, of which nearly half were structurally incomplete. The challenges of episcopal administration were magnified by the mixed ethnicity of his French and Irish flock, widespread spiritual deprivation, and the ever-increasing political and economic power of the local Protestant population.

Rogers believed that his first duty was to provide more priests. Specifically, he wanted indigenous priests with a facility in both French and English. Rogers also regarded the education and “moral culture” of youth as paramount concerns. To meet his objectives he established a small seminary in his own residence and employed the seminarians as instructors in a school for boys. In this way St Michael’s Academy, the parent institution of St Thomas’ University, was founded in 1860. In 1876 the Brothers of the Christian Schools, in response to Rogers’s persistent overtures, assumed its direction.

The bishop of Chatham also relied extensively on other religious orders, such as the Sisters of Charity, the Religious Hospitallers of St Joseph, and the Congregation of Notre-Dame. He solicited and encouraged their educational and charitable activities, incurring willingly the costs of their installation and flouting Archbishop Connolly’s command “Clear out everything that costs you anything.” In poorer missions Rogers assisted financially in the construction and completion of churches and presbyteries as well. In 1876 he proudly enumerated his diocese’s material improvements: three hospitals, seven academies for girls, two colleges for boys, and one orphanage. By 1879 the diocese had an impressive tally of 31 priests and 54 churches and chapels.

In spite of “the thousand little details” of diocesan administration, Rogers did not neglect the human dimension of his work. Most notably, he demonstrated solicitude for the lepers at the Tracadie lazaretto [see Amanda Viger] and for the “poor Indians,” who he believed were headed towards extinction. Concern for his flock prompted him to keep before politicians his diocese’s need for railway connections. He communicated with Rome infrequently, but during his ad Limina visit of 1869–70 he participated in the Vatican Council’s debate over papal infallibility, a doctrine which he, like Connolly, opposed elevating to an article of faith. On the same trip he collected donations in Belgium, France, and Austria for his diocesan projects and attended the Ecclesiastical Congress of Malines.

For Rogers, the responsibilities of office brought bitter-sweet satisfaction. He once compared the mitre to a “crown of thorns.” Ever-mounting financial obligations, for example, posed a grave problem. In 1866 he reported a diocesan debt of $12,000; by 1878 it had rocketed to $30,000. It rankled that his diocese had been launched without the customary fund for its foundation. This deficiency was compounded by modest parish offerings, chronic scarcity of specie, widespread seasonal unemployment, and out-migration. Thus the bishop found himself increasingly entangled in a web of promissory notes, floating loans, and mortgages.

Rogers’s monumental debt did not escape the censure of Connolly, who railed against his thriftlessness and in December 1866 threatened to assume temporary administration of the diocese. Connolly also accused the bishop of neglecting his official correspondence, the much-needed “grandeur” of his office, and his own intellectual self-improvement. But an unapologetic Rogers refused to be stalled by economies or episcopal etiquette. From his perspective, his constant personal intervention in the mission field and his costly projects had enriched the diocese and kept it from collapse.

In 1870 the mental instability of Father Hugh McGuirk, missionary priest at Saint-Louis-de-Kent, posed a special administrative challenge for Rogers. Although Rogers ordered McGuirk’s temporary suspension, the enraged cleric resisted by locking the church at Saint-Louis-de-Kent and storming the local presbytery with an axe. The whole affair proved an embarrassment to Rogers, even more so when McGuirk launched a painful and protracted lawsuit, charging his successor, Father Marcel-François Richard*, with defamation.

On 14 Feb. 1878 Rogers endured another crisis: a fire destroyed the cathedral, the episcopal residence, and St Michael’s Commercial College in Chatham. At a time when he deserved to see his endeavours bearing fruit, he found himself rebuilding, canvassing donations, and “camping out” in temporary lodgings. In 1880 he sustained yet another blow with the departure of the Brothers of the Christian Schools and the closure of his college. Two years later the debt-ridden Collège Saint-Louis, a bastion of French-language education in Saint-Louis-de-Kent, also closed its doors. Rogers attributed these set-backs to a lack of funding, specifically casting blame on the provincial government’s policy of withholding subsidies from denominationally based schools.

Politics precipitated several crises for Rogers. During the early 1860s he had deliberately shunned “political strife,” but he deviated from this course in 1866 to raise a “warning voice” against pro-Fenian sympathies. At the same time he was drawn into the confederation debates, publicly endorsing local pro-confederate candidates and urging New Brunswickers to bow patriotically to the dictates of British statesmen. Rogers contended that the scheme would benefit his diocese by bringing increased population and improved trade, industry, and railway transportation. He soon found himself locked in a heated exchange with Timothy Warren Anglin* over the merits of union. Prelate and journalist traded opinions and insults through Anglin’s newspaper, as they jockeyed for the coveted status of spokesman for Irish Catholic New Brunswick.

In 1871 Rogers joined in the public uproar over New Brunswick’s secularizing Common Schools Act [see George Edwin King]. Believing that nothing could be gained from silence, he condemned the act as atheistic and tyrannical, a gross assertion of Protestant political power which subjected Catholic children to “worse than Herodian persecution.” He spurred on John Costigan* and Anglin, encouraging them as parliamentary champions to lead the appeal for federal intervention. Although Rogers openly supported the use of legal channels to overturn the controversial legislation, he also harboured sympathies for the desperate actions of Acadians during the Caraquet riots [see Robert Young]. These riots, he later claimed, had been incited by plotting government partisans, seeking a pretext to deploy force. In the summer of 1875, with Rogers’s moral support, Bishop Sweeny negotiated the so-called compromise which secured several major concessions under the act. The spirit of the law, however, remained unchanged. Shortly after, Rogers issued a pastoral letter exhorting his flock to cease their “active opposition”: “We must simply tolerate what we cannot prevent.” He held that Lower Canadian insistence in 1867 that education remain a provincial matter had effectively tied the hands of the federal government and imperilled the rights of Catholics in the rest of Canada.

Despite his grievances the bishop of Chatham was no firebrand. The cause of the “plighted faith,” he believed, would be ill served by inflammatory tactics. Throughout the 1880s and 1890s Rogers was a muted champion of Catholic rights and shied away from political activism. In 1891, for example, he abstained from signing a petition launched by Archbishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché* demanding repeal of Manitoba’s Public Schools Act of 1890. Not until 1894 did he hesitantly throw support behind the advocates of disallowance. Rogers’s stance reflected in part his distaste for religious strife, but there was another motive at work. The bishop had little concern for the French language in Manitoba or for the principle of dual official languages, a position that stemmed largely from personal fears of growing Acadian consciousness in his own diocese. In his mind, the promotion of the French language connoted mischief and demagoguery.

This issue has become for historians the most controversial aspect of Rogers’s career. Recent scholarship characterizes him as an enemy of the Acadian renaissance and reproaches him for favouritism towards Irish Catholics. The short-lived Collège Saint-Louis and its founder, Father Marcel-François Richard, have both been portrayed as victims of Rogers’s malice and bigotry. Throughout the 1880s the closure of the college remained a lightning-rod for rumours and recriminations. It also drove a deep wedge between Richard and Rogers. By 1891 their relationship had so deteriorated that Richard submitted a list of grievances to the Holy See, charging the bishop with the college’s suppression and numerous acts of personal vindictiveness. The bishop replied with a diatribe against Richard’s undutiful and unclerical conduct, and dismissed most of the allegations as bombastic distortion. He admitted, however, that he had considered the college at Saint-Louis-de-Kent a redundancy because of its proximity to the Acadian classical College of St Joseph’s in Memramcook [see Camille Lefebvre*], and that he had looked with disfavour upon the nationalistic leanings of the college staff and their French-language exclusivism. Pilloried in the Acadian press, the speeches of Senator Pascal Poirier*, and the writings of François-Edme Rameau de Saint-Père, Rogers thought of resignation in 1892. For the remainder of his career he maintained that he had been “the innocent victim” of a “conspiracy.”

During the 1860s and 1870s Rogers was not insensitive to balancing the needs of his ethnically varied diocese. In 1879, for example, it was served by 18 priests of French origin and 13 priests of Irish origin. In 1877, while contemplating a trip to Europe, he planned to invite as his companions a francophone and an anglophone to represent the dual elements in his diocese. Moreover his correspondence from the 1870s contains only benign references to the “little College of St. Louis.” Any preferential gestures towards his Irish flock usually sprang from Rogers’s conviction that this group, lacking the protection of language and geographically exposed to religious pluralism, was more likely than the Acadians to fall away from Catholicism.

In the 1890s the tone of Rogers’s administration changed. Feeling besieged as Acadian clergy and laity alike assailed the Irish-dominated episcopacy in the Maritimes and lobbied for an Acadian bishop, he posed as a guard against “irregular movements and exaggerations of the so called national spirit.” He considered a presumption the ambition to “Acadianize” the Catholic Church in New Brunswick, and bluntly warned Acadians against any notion that they had the same linguistic privileges as French Canadians. In 1890 he forbade some of his French-speaking clergy to attend the Acadian convention at Church Point. This conflict became personalized in his acrimonious relationship with Father Richard. A dynamic champion of the Acadian renaissance, the much-venerated priest represented a challenge to the authority of the ageing bishop.

By 1897 Rogers was beginning to feel the “wear and tear of life.” With his portly physique, enormous appetite for food, and legendary stamina for winter travel, he had always been blessed with a sturdy constitution. But now he brooded over his fading strength, the “malaise of duties unfulfilled,” and the good fortune of those fellow bishops who had served God in more “pleasant fields of duty.” He had seemed particularly harassed by the resurgence of religious tensions, the result of the Bathurst school controversy [see John James Fraser*]. Thus he began to contemplate securing a successor. To his credit, he named as potential candidates three anglophones and three francophones. In 1899 the New Brunswick-born Thomas Francis Barry was appointed his coadjutor with right of succession. The archbishop of Halifax, Cornelius O’Brien, nudged Rogers towards full retirement, pointedly advising “Let a new man begin with the new century.” Rogers would wait until 1902 to make this decision. On 16 Dec. 1900, however, he attempted to make his peace with old adversaries in an address in the pro-cathedral at Chatham, guaranteeing his ready compliance with any papal decision to erect a new Acadian diocese and seeking pardon for “any word or act by which I may have unintentionally given offence or pain.” On 22 March 1903 Rogers died at the Hôtel-Dieu in Chatham.

Descriptions of Rogers are as diverse as the assessments of his 42-year episcopate. To his admirers, he was an amiable, hospitable, and uncommonly generous cleric, whose endearing trade mark was his enthusiastic outbursts of “Hurray! Hurray!” His flaws were no more offensive than his overly sanguine nature, impracticality, long-winded sermons, and undisciplined sense of time. Rogers’s detractors, however, have left behind the picture of a tyrannical, partisan, and quick-tempered prelate. One disaffected cleric went so far as to characterize him as rough and violent, completely deficient in social breeding and intellectual refinement.

Rogers’s material accomplishments as bishop of Chatham cannot be gainsaid. He left a deep mark on his diocese, helping to furnish it with schools, hospitals, and priests. He was totally devoted to his calling, and possessed the courage and capacity to infuse energy and vision into his work. Not even the dictates of budgets or the reproofs of his superiors deterred him. The allegations that he neglected his Acadian flock are unwarranted. Regrettably, his turbulent relationship with Father Richard stands out as a jarring note in his career. A product of the world of Irish ecclesiastical leadership, Rogers was ill equipped to deal with the Acadian attack on his authority. Owing to his stubborn, sometimes irascible temperament, he also lacked the diplomatic skills to accommodate Acadian nationalist aspirations. Unwittingly, the resistance of the Irish Catholic episcopacy in the Maritimes served only to propel the movement for a separate Acadian diocese and an Acadian bishop; in effect, the hierarchy helped mobilize the forces and new order it sought to discourage. With his death, Rogers left an impressive but controversial legacy.

The most significant body of material relating to James Rogers’s episcopal tenure, including correspondence, pastoral letters, and a typescript biography, is to be found in the Arch. du Diocèse de Bathurst, N.-B., Groupe II/1-1-119 (fonds James Rogers). This material is also available on microfilm at PANB, MC 290, F 7652–58. Photocopies of letters from the diocesan collection pertaining to the New Brunswick schools crisis are available in the Rogers papers at UNBL, MG H26 Rep.

A formal portrait of Bishop Rogers is housed in St Michael’s Museum (Chatham, N.B.).

Publications by Rogers include: Statement of the case “McGuirk versus Richard” (Saint John, N.B., 1872); Circular letter of the Rt. Rev. James Rogers, d.d., bishop of Chatham, advising his flock to cease further opposition to the non-sectarian school law, . . . (Chatham, [1876.?]); and Funeral sermon: delivered at the solemn obsequies of the late Most Rev. Thomas L. Connolly, archbishop of Halifax, in St. Mary’s Cathedral, Halifax, Nova Scotia, on Monday, 31st July, 1876 (Chatham, [1876?]). Additional circulars and pastoral letters written by Rogers have been made available on microfiche by the CIHM and are listed in its Reg. One of his letters is reproduced under the title “Correspondance du début du siècle: lettre de Mgr Rogers, évêque de Chatham, au Rév. L.-N. Dugal,” in Le Brayon (Edmundston, N.-B.), 5 (1976–77), no.3: 10–13.

Arch. de la Propagation de la Foi (Paris), F-175a (Chatham, rapports sur l’état des missions, 1860–83) (mfm. at NA). Arch. of the Archdiocese of Halifax, Cornelius O’Brien papers, II, nos.34–37a; William Walsh papers, I, nos.55, 84–86; II, nos.105–20; III, no.208b. Arch. of the Diocese of Saint John, Sweeny papers, nos.1455–94, 2107–24. Arch. of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto, L (Lynch papers), AE09.06; AH32.119; W (Walsh papers), AB05.09. Archivio della Propaganda Fide (Rome), Acta, 270: ff.441–43; Nuova serie, 28: ff.31–35; 100: ff.752–58; 195: ff.85–111; 242: ff.388–403; 265: ff.57–79; Scritture originali riferite nelle Congregazioni generali, 1016: f.132; 1035: f.188; Scritture riferite nei Congressi, America settentrionale, 7: ff.505–6; 21: ff.705–9; 22: ff.670–71; 23: ff.317–64, 423–26, 1105–6; 24: ff.568–600; 30: ff.321–28, 590–95; 32: ff.127–57, 704–5, 1058–1168. Archivio Segreto Vaticano (Rome), Delegazione apostolica del Canadà, 6, 13, 178; Falconio letter-book, 1899–1902: 89, 103–4, 198, 218, 269, 289, 291–93, 342, 344, 349. Centre d’Études Acadiennes, Univ. de Moncton, N.-B., Fonds Placide Gaudet, 1.58-21, 1.65-19, 1.65-21; Fonds P.-A. Landry, 5.2-11, 5.5-8; Fonds M.-F. Richard, 8.1-2-20, 8.2-1-6, 8.3-5, 8.3-7, 8.4-2, 8.4-8. NA, MG 24, L3, 25 (transcripts); MG 26, F, 6–7; MG 27, I, D4, 1; D5. PANB, RS24, S90, PE115, file 2.

Courrier des Provinces maritimes (Bathurst), 11 juill. 1901, 26 mars 1903. L’Évangéline, août 1890 (special illustrated edition, with biographical notes and engraving of Rogers); 2, 9 avril 1903. Gleaner (Chatham), 25 Aug. 1860, 7 July 1870. Le Moniteur acadien, 30 sept., 23 déc. 1870; 4 févr., 18 nov. 1875; 27 sept. 1877; 10 avril 1879; 10 juin 1882; 14 juin 1883; 19 juin, 4 sept. 1884; 20 août 1885; 15 nov. 1887; 20 janv. 1888; 12 juill. 1900; 11 juill. 1901; 26 mars, 2 avril 1903. New Freeman (Saint John), 28 Nov. 1953.

The Acadians of the Maritimes: thematic studies, ed. Jean Daigle (Moncton, 1982). Allaire, Dictionnaire, 1: 478. Canadian biog. dict. Maurice Chamard et al., Le père Camille Lefebvre, c.s.c. (Montréal, 1988). C.-A. Doucet, Une étoile s’est levée en Acadie ([Rogersville, N.-B.], 1973). “The 1866 election in New Brunswick: the Anglin–Rogers controversy,” ed. W. M. Baker, Acadiensis (Fredericton), 17 (1987–88), no.1: 97–116. J. A. Fraser, “By force of circumstance”: a history of St. Thomas University (Fredericton, 1970). M. F. Hatfield, ‘“La guerre scolaire’ – the conflict over the New Brunswick Common Schools Act” (ma thesis, Queen’s Univ., Kingston, Ont., 1972). F. C. Kelley, The bishop jots it down: an autobiographical strain on memories (New York and London, 1939). Corinne LaPlante, “Monseigneur James Rogers,” Dictionnaire biographique du nord-est du Nouveau-Brunswick (5 cahiers parus, [Bertrand; Shippagan, N.-B.], 1983– ), 3: 52–54. J. I. Little, “New Brunswick reaction to the Manitoba schools’ question,” Acadiensis (Fredericton), 1 (1971–72), no.2: 43–58. J. M. McCarthy, Bermuda’s priests: the history of the establishment and growth of the Catholic Church in Bermuda (Quebec, 1954). A. L. McFadden, “The Rt. Rev. James Rogers, d.d., first bishop of Chatham, N.B.,” CCHA Report, 15 (1947–48): 53–58. [F.-E.] Rameau de Saint-Père, Une colonie féodale en Amérique; l’Acadie (1604–1881) (2v., Paris et Montréal, 1889). Silver jubilee celebration of their lordships bishops McIntyre and Rogers: Charlottetown, August 12, 1885 (n.p., [1885?]). M. S. Spigelman, “The Acadian renaissance and the development of Acadien-Canadien relations, 1864–1912, ‘des frères trop longtemps séparés’” (phd thesis, Dalhousie Univ., Halifax, 1975). Léon Thériault, “Les origines de l’archévêché de Moncton, 1835–1936,” Soc. Hist. Acadienne, Cahiers (Moncton), 17 (1986): 111–32. P. M. Toner, “The foundations of the Catholic Church in English-speaking New Brunswick,” New Ireland remembered: historical essays on the Irish in New Brunswick, ed. P. M. Toner (Fredericton, 1988), 63–70; “The New Brunswick separate schools issue, 1864–1876” (ma thesis, Univ. of N.B., Fredericton, 1967). K. F. Trombley, “Thomas Louis Connolly (1815–1876): the man and his place in secular and ecclesiastical history” (phd thesis, Katholieke Univ. Leuven, Belgium, 1983; photographic copy privately issued by the author, Saint John, 1983). Onésiphore Turgeon, Un tribut à la race acadienne: mémoires, 1871–1927 (Montréal, 1928).

Cite This Article

Laurie C. C. Stanley, “ROGERS, JAMES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 21, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rogers_james_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rogers_james_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Laurie C. C. Stanley |

| Title of Article: | ROGERS, JAMES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | January 21, 2025 |