Source: Link

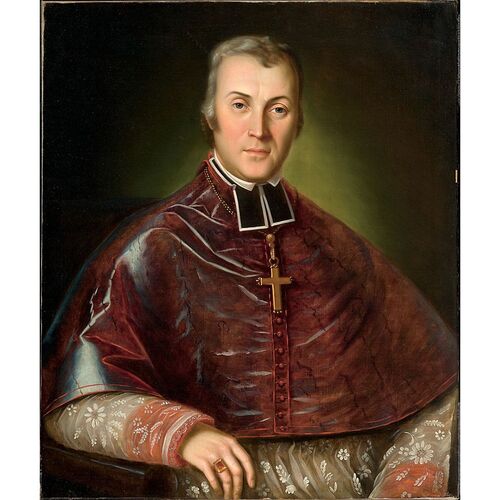

TURGEON, PIERRE-FLAVIEN, priest, educator, archbishop; b. 12 Nov. 1787 at Quebec, son of Louis Turgeon, a merchant, and his second wife, Louise-Élisabeth Dumont; d. 25 Aug. 1867 in the same city.

Pierre-Flavien Turgeon belonged to the sixth generation of a family from the department of Perche whose ancestor settled at Beauport, near Quebec, in the summer of 1662. His half-brother, Louis Turgeon, who was the first of three descendants to sit on the Legislative Council, acted as his guardian after his father’s death in 1800. Pierre-Flavien had been admitted into the Séminaire de Québec the preceding year. As a youth he attracted attention by his unusual intellectual and moral precociousness. In 1806, before his year of rhetoric was completed, Joseph-Octave Plessis*, who had become bishop of Quebec in January, noticed him and appointed him his secretary. While acting in this capacity Turgeon was obliged to take philosophy and to pursue the regular ecclesiastical studies before being ordained a priest on 29 April 1810, the age limit having been waived. The Séminaire de Québec claimed his services, although he did not give up his post as the bishop’s close assistant in the administration of the diocese.

At the Séminaire de Québec, where he was to stay for 22 years, Turgeon soon undertook various duties. He was fully qualified to teach by the autumn of 1811, professor of philosophy (1812–15), director of the Grand Séminaire (1815–18) and of the Petit Séminaire (1820–24). His intellectual capacity, special gift in psychology, and never-failing kindness made him a master revered by his pupils and a counsellor valued by many ecclesiastics. In the conduct of diocesan affairs he enjoyed the bishop’s complete confidence. Between these two very different men a friendship was created that death alone would sever. Bishop Plessis clearly was preparing Turgeon to succeed him. The intense activity Turgeon was involved in proved too exacting, however, and illness, from which he was to suffer all his life, forced him to take periods of rest. Acting on this need he accompanied Bishop Plessis to Europe in 1819, his only voyage overseas. In the summer of 1822 he went to the diocese of Boston for another rest cure. His health did not permit him to resume teaching, and he was appointed bursar of the Séminaire de Québec in 1824. During his nine years of management, he inaugurated administrative reforms that improved the temporal affairs of the seminary which had been in a precarious state since the Conquest.

In 1825 Bishop Plessis was preparing to call Turgeon to the episcopate, to succeed Bishop Bernard-Claude Panet*, who wanted to give up the office of coadjutor because of his advanced age. But Plessis died before he did so. Turgeon was barely 38. Panet, who had become titular bishop, urged him to accept the mitre, reinforcing his request with a laudatory letter from the governor, Lord Dalhousie [Ramsay*]. From the Hôpital Général where he was confined by illness, Turgeon firmly declined in favour of Joseph Signay*, parish priest of Quebec. His action saddened his friend and travelling companion in Europe, Bishop Jean-Jacques Lartigue*, who at that time was assistant to the bishop of Quebec in the district of Montreal.

When Bishop Panet died in 1833, Turgeon could not continue to resist the pleas of the clergy. Signay, the new bishop, succeeded in having him elected as coadjutor and the election recognized by the civil government early in 1833 in spite of the insidious opposition at Rome of the Séminaire de Montréal. The French faction of the latter was trying to obtain the appointment of bishops who were firm supporters of their cause, favourable to recruiting French personnel, and prepared to negotiate with the government to obtain compensation for the Sulpicians’ seigneurial rights. As a result of this faction’s intrigues in Rome, Jean-Baptiste Saint-Germain, a great friend of the Sulpicians and parish priest of Saint-Laurent near Montreal, was selected by the Propaganda to be Bishop Signay’s coadjutor. But as Pope Gregory XVI delayed approving this choice, Bishop Signay sent Abbé Thomas Maguire* from Quebec to offset the influence of the Sulpician Jean-Baptiste Thavenet* at Rome; Thavenet had described Turgeon as a personal enemy of the Sulpicians, and maintained that he had not been approved by Rome but had been appointed coadjutor by the governor. Maguire’s mission secured the appointment of Turgeon. Gregory XVI in the end decided in his favour, and by a brief dated 28 Feb. 1834 appointed him bishop in partibus of Sidyme and coadjutor to Bishop Signay, with right of succession. Bishop Signay had already announced his election as coadjutor on 25 Feb. 1833 in his pastoral letter of installation. This move had been thought ill timed by Bishop Lartigue, who did not know that, in accordance with directives from Rome concerning the method of election of bishops, Turgeon had been recognized as early as 1829 as one of three priests worthy of elevation to the episcopate. Because of this action, which had been kept secret out of fear of antagonizing a Protestant government, Turgeon was actually the first Canadian bishop whose selection was approved by Rome and then by the civil government.

On 11 June 1834 Pierre-Flavien Turgeon received episcopal consecration from Bishop Signay, assisted by Bishop Lartigue and Bishop Rémi Gaulin*, coadjutor to the bishop of Kingston. Bishop Turgeon began his duties when the diocese of Quebec was struggling to recover from the confusion that followed the unexpected death of Bishop Plessis. During the 16 years of authority shared with Bishop Signay, he worked with fervour and zeal to consolidate the work Bishop Plessis had begun for the maintainenance of the faith and the advancement of the church. He gave of himself unsparingly, despite the illnesses that were to put a premature end to his career.

Bishop Turgeon was responsible for directing religious communities, particularly the Ursulines of which he was the ecclesiastical superior for 19 years; he also was entrusted with much of the temporal administration of the church: the incorporation of parishes, building and repair of churches, and work with the government on legislation relating to religious matters. He won his case with the Propaganda in 1844 in the dispute concerning the accounts for the income of religious communities in Canada which Thavenet had rendered. He was conscious of the role of the church in public life and believed it should intervene in the solution of any problems facing the country where, in his view, the interests of religion were at stake. Thus in February 1838, in a petition he had the clergy sign, which was presented to the imperial parliament, he emphatically objected to the projected union of the two Canadas and asked that the constitution of 1791 be maintained. When the anti-union movement was organized at Quebec in January 1840, under the presidency of John Neilson* [see René-Édouard Caron*], he joined the clergy in signing a new petition, and personally canvassed for money to meet the expenses incurred in London by Vital Têtu, the bearer of the citizens’ address.

The bishop made the spiritual renewal of the diocese the cornerstone of his work as an apostle. He played a large part in establishing pastoral retreats and developing popular retreats by bringing Bishop Charles-Auguste-Marie-Joseph de Forbin-Janson* to Quebec in 1840. In his determined struggle against intemperance, he applied himself to promoting campaigns in the diocese and temperance associations in each parish. In 1844, following his pastoral visits to the missions in the Gulf of St Lawrence, the Oblates of Mary Immaculate were brought into the diocese, to assume responsibility for preaching the gospel in the Saguenay missions and at the king’s posts as far as Labrador. In 1849, to assist the clergy of the episcopal city, he obtained permission for the Jesuits to return to Quebec.

Bishop Turgeon was primarily a priest devoted to social causes. Throughout his whole career he took an interest in education. For many years he was special procurator and member of the corporations of the Séminaire de Nicolet and the Collège de Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière in order to place these educational establishments on a sound footing. He supported the parish council schools, and in 1842, through Bishop Forbin-Janson, he introduced the Brothers of the Christian Schools into the diocese. He actively assisted Bishop Signay in setting up the Ladies of the Congregation of Notre-Dame in the faubourg Saint-Roch at Quebec [see Marie-Louise Dorval]. He urged that the income from the Jesuit estates be devoted to the work of Catholic education and strenuously fought the system of non-denominational education proposed by Lord Durham [Lambton*] and defined by Arthur William Buller. Impelled by both religious and patriotic motives, he strongly favoured encouraging colonization, and for a time (from August 1848) was president of an association in the district of Quebec which encouraged settlement in the Eastern Townships. His pastoral letter of 11 Aug. 1848 earnestly recommended this work to the clergy as the most effective means of curbing emigration to the towns and to the United States.

His concern for the poor and underprivileged was so great that he rightly acquired the reputation of being an apostle of charity. After the cholera epidemics in 1832 and 1834, Quebec was laid waste by two conflagrations that levelled the faubourgs Saint-Roch and Saint-Jean. In 1847 typhus brought heavy casualties, then a new cholera epidemic struck in 1849. The bishop spared neither energy nor money in the effort to meet the immense needs of the destitute and the orphans. His urgent appeals for charity never went unheeded. He was anxious also to provide the diocese with charitable organizations. Thus he supported in 1846 the timely initiative of Dr Joseph Painchaud*, founder of the Society of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul. He also helped to establish two religious communities. In 1849 he recruited the Sisters of Charity of the Hôpital Général de Montréal, who under the direction of Sister Marie-Anne-Marcelle Mallet* came to open a house for the care of orphans and the education of poor children. In 1850, with the assistance of Marie Fisbach*, he founded the Asile du Bon-Pasteur for the moral reformation of young girls.

When he had agreed to be coadjutor to Bishop Signay, Turgeon had taken on a post requiring tact. As assistant to a zealous but autocratic and aloof bishop, who through excessive prudence resisted both innovations and easy sharing of responsibilities, Bishop Turgeon managed to control numerous vexatious situations in the immediate entourage of the head of the diocese. Since his concern for preserving the bonds of solidarity between the local churches was well known, Bishop Lartigue and Bishop Ignace Bourget* left to him the task of pleading their case before Bishop Signay. By his patience he was instrumental in protecting unity in church government in a period when the district of Montreal was at the height of its development and relations between the heads of the two dioceses were often strained. It was largely his courageous intervention that brought to a successful conclusion in 1844 a long debated project, the establishment of the first ecclesiastical province with a metropolitan see at Quebec. Bishop Signay had long been opposed, alleging among other reasons that without a bishop’s palace he would not have a place in which to assemble the suffragans. Bishop Turgeon volunteered to assume all responsibility for building a palace, and urged his superior to seek incorporation of the bishopric of Quebec; this was granted in January 1845. Construction, which was begun in the spring of 1844 following the plans of the architect Thomas Baillairgé*, was interrupted by the 1845 fire at Quebec and by lack of resources. In November 1847, however, the edifice, which still stands, was finally ready for inauguration; Bishop Turgeon had himself directed its construction.

In the autumn of 1846, Bishop Bourget went to Rome to ask for the resignation of Bishop Signay, who in his opinion had totally failed to take up the duties of a metropolitan. Bishop Turgeon thought he could discern in the sharp reactions of Bishop Signay a suspicion of intrigue, which dismayed him so much that he sent a telegram to Bishop Bourget, urging him to ask Rome to accept his own resignation as coadjutor. There were no results from Bishop Bourget’s agitation.

On 10 Nov. 1849 Bishop Signay, increasingly in ill health, entrusted the administration of the archdiocese to his coadjutor, who was then 61. An essential difference between Bishop Turgeon’s approach and the archbishop’s quickly became apparent. The ecclesiastical province had existed for five years, and Turgeon was too devoted to the interests of the church in Canada to postpone further bringing the suffragans together. Although he was only an administrator he obtained authorization from Rome to convoke the first provincial council to be held in Canada. To spare Bishop Signay’s feelings, he presided over a preliminary assembly of bishops at Montreal, which fixed 15 Aug. 1851 as the opening date of the council. But on 3 Oct. 1850 Bishop Signay died. Five days later Bishop Turgeon assumed the authority of the metropolitan see of Quebec. He obtained as his coadjutor Charles-François Baillargeon, then agent for the bishops of the ecclesiastical province of Quebec in Rome. After the first provincial council, which marked an important stage in the organization of the church in Canada, Bishop Turgeon called a second council in 1854.

Bishop Turgeon’s name has remained closely linked with the founding of Université Laval, in which he played a decisive part. His predecessors and Bishop Bourget had wanted to found a Catholic university earlier, and the aim had been expressed at the first provincial council. The negotiations initiated by Bishop Turgeon at the end of 1851 with the Séminaire de Québec and Bishop Bourget were brought to a successful conclusion with remarkable dispatch. In its plan Montreal proposed a provincial university under the jurisdiction of the bishops; Turgeon countered with the more realistic project of a diocesan university under the authority of the archbishop of Quebec, with affiliation open to the other colleges of the ecclesiastical province. His plan was accepted. Bishop Bourget advocated only papal recognition of the establishment, but Turgeon had already secured civil recognition in the summer of 1852 [see Louis-Jacques Casault]. The archbishop’s pastoral letter announcing the creation of Université Laval shows the fundamental importance he attributed to this undertaking, and the lofty conception he had of classical and university studies.

Turgeon’s career as an archbishop lasted barely five years, but the stimulus he was able to give to his diocese made it significant. In order to reorganize the upper level of the administration, he created a special council of seven members and a general council of 13, displaying by the thrust of these structures of consultation and coordination an unprecedented example of collegiality in the church in Canada. The formation of the dioceses of Trois-Rivières and Saint-Hyacinthe in 1852 apparently lightened his pastoral task, but the rapid growth of the population and the attachment of the Labrador coast to Quebec in February 1853 added to his cares. As well as the six vicars general already in office, he was able to add two excellent men to his staff: Charles-Félix Cazeau*, his vicar general, and Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Ferland.

In addition to ensuring that regular pastoral visits were conducted, Bishop Turgeon created ten new parishes and founded several missions. He continued also to promote charitable works and gave particular attention to the spiritual renewal of his clergy, by maintaining pastoral retreats and re-establishing ecclesiastical conferences. The archbishop carried out enlightened revision of theological studies and the training of ecclesiastics, and for the first time in the Canadian church he sent priests to Rome and Paris to pursue advanced studies. He promulgated and immediately put into effect the prescriptions of the provincial councils, chiefly its decrees concerning discipline, the catechism, and ritual.

His written work includes pastoral letters and instructions that reveal the extent of his doctrinal and pastoral concerns. It also contains notes, never published, evaluating Bishop Plessis. He drew up these notes in October 1849, at the request of Édouard-Gabriel Plante, the vicar at Quebec, apparently to end slander circulating about the bishop. The document provides a portrayal of the personality of Bishop Plessis unmatched anywhere, and makes one regret that Turgeon, at the death of the archbishop, declined the invitation of his friend Jacques Viger* to draft a biographical notice for La Bibliothèque canadienne.

At the time when Bishop Turgeon was exerting himself to the utmost, illness and exhaustion prevailed over his aptitude for hard work and his extraordinary apostolic spirit. On 19 Feb. 1855 he suffered an attack of hemiplegia. As the disease proved incurable, he handed over the administration of the diocese to his coadjutor, Bishop Baillargeon, on 11 April. He lived some 12 years longer, partly deprived of the faculty of speech. He died on 25 Aug. 1867.

Tall, with an expressive face, Bishop Turgeon was remembered as a remarkable man who, “by his keen intelligence, his affable behaviour, his gentle and likeable character, had won the esteem even of those who did not share his beliefs.” Those who knew him regretted, with Bishop Lartigue, that he had not accepted the episcopate immediately after the death of Bishop Plessis in 1825 so that he could have presided over the destinies of the church in Canada at the time when, after gaining her autonomy, she was entering a decisive phase of expansion and development. In his pastoral letter of 18 Dec. 1843 to his diocesans, Bishop Turgeon proudly stressed their zeal for “the relief of suffering humanity, [and] the furtherance of religion and education in this country.” These words sum up both his ideal of ministry and the most outstanding achievements of his episcopate.

[The most important of Bishop Turgeon’s papers are preserved in the AAQ. A partial inventory for the period 1833–40 was published in the ANQ Rapport, 1936–37, 1937–38, 1938–39. For the years 1833–50, the ACAM holds more than 375 of Turgeon’s letters; a small number of copies are in the AAQ. In addition to the Verreau and Université Laval collections, the ASQ holds numerous documents relating to Turgeon. The Canadian material in the Archives de la Compagnie de Saint-Sulpice in Paris, which was inventoried in ANQ Rapport, 1969, contains interesting information.

There are only short biographical sketches of Bishop Turgeon; among the least imperfect is the one by Mgr Henri Têtu* in his Notices biographiques: les évêques de Québec (Québec, 1889), 583–616, and the opuscule Souvenir consacré à la mémoire vénérée de Mgr P.-F. Turgeon, archevêque de Québec et premier visiteur de l’université Laval (Québec, 1867), which contains the prelate’s funeral eulogy by Abbé Benjamin Paquet* and a biographical notice by Abbé Cyrille-Étienne Légaré. For the period 1833–44, Lucien Lemieux’s study, L’établissement de la première prov. eccl., 299–402, is useful. This work, one of the first in Canadian Catholic history to be based on a parallel examination of both European and Canadian archives, gives a good outline of Turgeon’s activity during ten years of the life of the church in Canada, and affords the best synthesis of the opposition that marked his appointment to the episcopate. a.g.]

J.-B.-A. Ferland, “Journal d’un voyage sur les côtes de la Gaspésie,” Les Soirées canadiennes; recueil de littérature nationale (Québec), 1 (1861), 301–476. Mandements des évêques de Québec (Têtu et Gagnon), III, IV. [J.-O. Plessis], Journal d’un voyage en Europe par Mgr Joseph-Octave Plessis, 1819–1820, Henri Têtu, édit. (Québec, 1903). [H.-R. Casgrain], L’asile du Bon-Pasteur de Québec d’après les annales de cet institut (Québec, 1896), 43–185. Une fondatrice et son œuvre: mère Mallet (1805–1871) et l’Institut des sœurs de la Charité de Québec, fondé en 1849 (Québec, 1939), 93–275, 425–30. P. B. Gams, Series episcoporum ecclesiae catholicae, quotquot innotuerunt a beato Petro apostolo (3 pts., Ratisbon, Germ., 1873–86), pt.i, 177. Jacques Grisé, “Le premier concile provincial de Québec, 1851” (mémoire de des, université de Montréal, 1969). L’œuvre d’un siècle; les Frères des écoles chrétiennes au Canada (Montréal, 1937), 80–84, 302. Henri Têtu, Histoire du palais épiscopal de Québec (Québec, 1896), 105–80. René Bélanger, “Visite de Mgr Turgeon aux Ilets-de-Jérémie en juillet 1846,” Saguenayensia (Chicoutimi, Qué.), 9 (1967), 38–39. Philippe Sylvain, “Les difficiles débuts de l’université Laval,” Cahier des Dix, 36 (1971), 211–34.

Cite This Article

Armand Gagné, “TURGEON, PIERRE-FLAVIEN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/turgeon_pierre_flavien_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/turgeon_pierre_flavien_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Armand Gagné |

| Title of Article: | TURGEON, PIERRE-FLAVIEN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | March 30, 2025 |