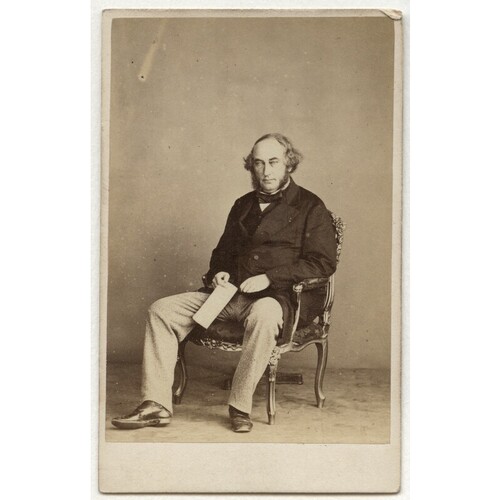

![Sir Arthur William Buller. Image by Clarkington & Co (Charles Clarkington). [albumen carte-de-visite, 1860s]

NPG Ax8655 - National Portrait Gallery, St Martin's Place, London WC2H OHE

Source: https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp102726/sir-arthur-william-buller

Used under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Original title: Sir Arthur William Buller. Image by Clarkington & Co (Charles Clarkington). [albumen carte-de-visite, 1860s]

NPG Ax8655 - National Portrait Gallery, St Martin's Place, London WC2H OHE

Source: https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp102726/sir-arthur-william-buller

Used under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/](/bioimages/w600.13866.jpg)

Source: Link

BULLER, Sir ARTHUR WILLIAM, member of the Executive Council and the Special Council of Lower Canada and head of a commission of inquiry into education; b. 5 Sept. 1808 at Calcutta, India, son of Charles Buller, a civil servant in Bengal, and Barbara Isabella Kirkpatrick; m. Annie Templar in 1842; d. 30 April 1869 in London, England.

Arthur William Buller received his primary education at Edinburgh and entered Trinity College, Cambridge, where he obtained a ba (1830) and ma (1834), before being called to the bar. On 27 May 1838 Arthur William and his brother Charles* reached Quebec with Lord Durham [Lambton*], whom the British parliament had instructed to investigate the situation in Lower Canada following the rebellion. Noting the deplorable state of education in the province, Durham on 4 July made Buller a commissioner responsible for conducting an inquiry into it. Buller, who had become a member of the Executive Council of Lower Canada on 28 June, was to “proceed with the utmost despatch to inquire into and investigate the past and present modes of disposing of the produce of any Estate or Funds applicable to purposes of Education in Lower Canada. . . .” His commission further stipulated that it was “expedient and desirable that such a system of education should be established as may conduce to the diffusion of knowledge, religion and virtue,” and Buller was to make suggestions with this end in view. To carry out his undertaking, Buller could question individuals, consult public documents, laws, and official papers, and if necessary co-opt assistant commissioners possessing the same authority.

Anxious to complete his inquiry successfully, Buller, with the assistance of his secretary Christopher Dunkin*, prepared a questionnaire for prominent persons and priests of each parish in order to collect as much information as possible about the organization of the school system. However, the majority of people able to provide him with useful data dissociated themselves from the inquiry, and some even attempted to prevent its completion. Buller then had recourse to an associate, who collected information and classified it, and had some of it sent to Buller in England after his departure in November. The inquiry was conducted with numerous consultations, and received newspaper publicity. Bishop Jean-Jacques Lartigue* of Montreal agreed in spite of his distrust to give the commissioner information about the Catholic schools in his diocese. Le Populaire, a Montreal newspaper directed by Hyacinthe-Poirier Leblanc de Marconnay, published 21 articles on education from 23 July to 29 Oct. 1838. Dr Jean-Baptiste Meilleur* also replied to Buller’s invitation, and outlined his views on education in a series of seven articles, published in Le Populaire in August 1838 and reprinted in Le Canadien of Quebec. All the suggestions, which were well received, did not however correspond with the purposes of the investigators, who wanted to anglicize the French Canadians. The inquiry, begun 1 August, was concluded in November 1838, such a brief period being clearly insufficient time for an accurate appreciation of a complex situation.

Buller’s report, curiously, was dated 18 Nov. 1838 (three days before he left for England), but was presented to the British parliament in June 1839. It consisted of two parts: one on the past and present state of education in Lower Canada, the other on a future system of national education. In the first part, which contained the results of his inquiry, Buller studied the content and application of the various school acts since 1801. He repeatedly insisted that education grants had served political ends, and had helped only to further the interests of the Parti Canadien of Louis-Joseph Papineau*, rather than those of the schools. In addition he stressed the sterling qualities of the common people of Lower Canada and of Canadian women, criticized the unimaginative farming practices of the Canadiens, and praised the seminaries run by the Catholic clergy, particularly the seminary of Quebec and the work of Abbé John Holmes*.

After this brief historical outline, Arthur Buller sketched his new school system, based on the anglicization of French Canadians, the exclusion of politics from schools, religious instruction, and the imposition of an obligatory school tax. To attain the first objective, Buller proposed that the youth of both races should be brought together as often as possible in the same schools and through games and social activities. After some thoughts on how politics might be kept out of the schools, Buller tackled the delicate problem of religious instruction. As there were a certain number of points on which all Christians agreed, he advocated the creation of a committee responsible for selecting biblical passages acceptable to all, and preparing commentaries for each section of the catechism. If any one of the religious denominations found this teaching inadequate, it could add the religious instruction it deemed essential after school. This proposal aroused serious objections on the part of the Catholics, who thought the Catholic church alone should be responsible for education. For their part, the Protestants considered that Buller’s plan undermined the very principle of free interpretation of the Bible.

To settle the problem of school financing, Buller suggested a direct tax be imposed. In his opinion the taxpayers (landed proprietors) and the public treasury should provide at least an equal amount, state aid from then on being only complementary to the voluntary efforts of each school district.

Further on in his report, the commissioner foresaw the establishment of primary, model, and normal schools, institutions of higher or academic learning, and a university at Quebec. He also insisted on the training of good teachers who would be expressly forbidden to engage in political activity, on pain of dismissal. To Buller’s way of thinking the new school system must be based on the close control of teaching. He therefore devised a plan of inspection and supervision for the future national schools from which the Catholic clergy would be totally excluded.

Buller’s report, which advocated a system of education inspired by those of the United States and Prussia, and sought primarily to unify the two races of Lower Canada by anglicizing French Canadians, was far from perfect. Prepared rapidly by an official who was completely ignorant of the problems peculiar to Lower Canada and had stayed in the country only briefly, the report contained erroneous statements and unrealizable plans. On the other hand, it offered some interesting suggestions, for instance concerning the exclusion of politics from schools, recruitment of future masters, teaching of agriculture in the normal schools, and improvement of teachers’ salaries. Other proposals, such as the establishment of municipalities responsible for local problems, of the post of superintendent of education, and of a permanent education fund accruing from the Jesuit estates, the clergy reserves, and compulsory taxes, were to appear in the various school acts of the 1840s. In 1841 Buller’s report, which was ill received by Canadian religious authorities, inspired Charles-Elzéar Mondelet* to write his Letters on elementary and practical education. The latter influenced the drafting of an education bill which was presented by Governor Sydenham [Thomson*] and passed on 18 Sept. 1841.

Arthur Buller was also a member of the Special Council from 22 Aug. to 2 Nov. 1838. He returned to England on 21 November. In 1840 he was appointed crown attorney in Ceylon, and held this post until 1848. He was made a judge of the Supreme Court of Calcutta and served in that capacity until 1858. Buller died in April 1869 in London, after being a member of the British House of Commons for ten years.

[J. G. Lambton], Lord Durham’s report on the affairs of British North America, ed. C. P. Lucas (3v., Oxford, 1912), III; Le rapport de Durham, M.-P. Hamel, trad. et édit. (Montréal, 1948). Le Populaire (Montréal), août–sept. 1838. Boase, Modern English biog., I, 469. Debrett’s illustrated peerage and baronetage of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (London, 1868). Desjardins, Guide parlementaire. L.-A. Desrosiers, “Correspondance de Mgr Lartigue et de son coadjuteur, Mgr Bourget, de 1837 à 1840,” ANQ Rapport, 1945–46. L.-P. Audet, Hist. de l’enseignement, I, 386–403; Le système scolaire, VI. L.[-A.] Groulx, L’enseignement français au Canada (2v., Montréal, 1931–33). André Labarrère-Paulé, Les instituteurs laïques au Canada français, 1836–1900 (Québec, 1965).

Cite This Article

Louis-Philippe Audet, “BULLER, Sir ARTHUR WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/buller_arthur_william_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/buller_arthur_william_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Louis-Philippe Audet |

| Title of Article: | BULLER, Sir ARTHUR WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1976 |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |