Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

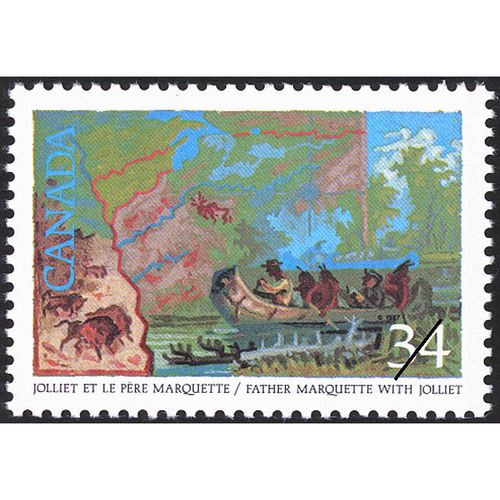

JOLLIET, LOUIS, explorer, discoverer of the Mississippi, cartographer, king’s hydrographer, teacher at the Jesuit college at Quebec, organist, business man, and seigneur; baptized 21 Sept. 1645 at Quebec, son of Jean Jollyet, a wheelwright in the service of the Compagnie des Cent-Associés, and of Marie d’Abancourt; d. 1700 in New France.

Can the historian fail to deplore the ill luck that seems to have dogged the personal papers of Louis Jolliet and the documents concerning him? Various mishaps and regrettable omissions have as it were wantonly contrived to set up zones of silence and obscurity in the career of this great Canadian. The trouble begins even with his birth, of which we know neither the place nor the date. Was he born at Quebec, on the Beaupré shore or in one of the adjoining seigneuries, territories which in 1645 all came within the boundaries of the parish church of Quebec where he was baptized? The certificate of baptism dated 21 Sept. 1645 gives no precise details on the place, any more than on the date of birth of this child “recens natum.”

Louis Jolliet was only five and a half when he lost his father, 23 April 1651. His mother married again on 19 October; her second husband was Gefroy Guillot, who was drowned in the St. Lawrence in the summer of 1655. On 8 Nov. 1665 Marie d’Abancourt was married a third time, to Martin Prévost.

Around the age of 11, Jolliet entered the college of the Jesuits at Quebec, where he did his classical studies. Intending to enter the priesthood, he took the minor orders, 19 Aug. 1662. At that time Jolliet was already becoming interested in music, and he shared with Germain Morin* the title of music officer in the college. As first organist of the cathedral of Quebec, he apparently played the organ from 1664; a document of 1700 states that he “played on the organ” there for “many years.”

In 1666, Jolliet – whom the census of that year styles a “cleric” – was finishing his philosophical studies. On 2 July, together with Pierre Francheville*, he defended a “thesis in philosophy.” Bishop Laval*, MM. Prouville de Tracy, Rémy de Courcelle, and Talon were present. “Monsieur the Intendant, among others, made a strong argument,” noted the Journal des Jésuites; “Monsieur Joliet and Pierre Francheville replied very well, upon the whole subject of logic.” This “disputation,” as was the custom, must have been conducted in Latin, a language that Jolliet knew well; he would have recourse to it in 1679 in Hudson Bay.

No longer feeling drawn towards a priestly vocation, Jolliet left the seminary around the month of July 1667. In October, thanks to a sum of 587 livres lent by Bishop Laval, he embarked for France. We do not know the object of this voyage, during which he stayed in Paris and at La Rochelle, dividing his time about equally between the two cities. He must have devoted some thought, however, to the direction that he would henceforth give to his life. When he returned to Quebec his mind was made up: on 9 Oct. 1668 he bought from Charles Aubert* de La Chesnaye a considerable stock of goods for fur-trading. Jolliet would be a fur-trader! But in this vast country of New France, with its inviting rivers and ready mirages, one temptation awaited fur-traders and travellers: exploration. Would the erstwhile “cleric” succumb to it?

Although having a rich supply of merchandise, Jolliet apparently did not leave for the West in the autumn of 1668. He was certainly at Quebec on 14 October, and perhaps at Cap-de-la-Madeleine on 9 November, which were very late dates for undertaking such a journey; his presence is further vouched for at Quebec, 13 April 1669, too early for him to be already back from the Great Lakes, unless one assumes that he returned before the melting of the snows and the break-up of the ice. But it is difficult to concede that an inexperienced traveller like Jolliet would have plunged into an adventure dreaded by the most hardened and by the most courageous coureurs de bois. It is more likely that he spent the winter at Quebec. How then did he dispose of his fur trading goods? Did he keep them for a journey that he may have made in 1669–70? It is not impossible, although we possess no indication of it. In 1669, it is true, a “sieur Jolliet” set off with Jean Peré, in search of a copper mine on Lake Superior, but it has been possible to demonstrate that this is a reference to Adrien, Louis’s brother. In short, it must be admitted that with the exception of his presence at Quebec 13 April 1669, nothing is known of Louis Jolliet from the autumn of 1668 to the summer of 1670.

On 4 June 1671, at the Sainte-Marie falls (Sault Ste. Marie), some Frenchmen “who were fur-trading in the locality” signed the document whereby Daumont de Saint-Lusson took possession of the territories of the West. Louis Jolliet was one of the number. He had probably left Quebec in the autumn of 1670; on 12 Sept. 1671 he was back. We do not know how he was engaged during the year that preceded his departure for the Mississippi, but it is certain that he did not go back to the West.

The Mississippi! The mysterious river that for nearly 15 years haunted the imagination of missionaries and explorers. In 1660 and 1662, on the assurance of the Indians, the Relation reported the existence towards the west of a “beautiful River, large, wide, deep, and worthy of comparison . . . with our great river St. Lawrence.” This river, which was thought to flow into the Gulf of Mexico, or, in the direction of California, into the “mer Vermeille” (Gulf of California), was not perhaps the Mississippi, the name of which will moreover appear (in the form “Messipi”) only in 1667; but at least, the missionaries’ investigations concerning this waterway did lead them to a knowledge of the Mississippi. In 1670, with only the information supplied by the Indians, the Jesuit Dablon managed to give a good description of it. The following year the Sulpicians Dollier* de Casson and Bréhant de Galinée became in their turn interested in the river that they named Ohio or Mississippi (“Ohio,” in the Iroquois language, and “Mississippi,” in the Ottawa language, both mean “beautiful river,” belle rivière). Thus, before any white man in New France had seen it, and although inevitably some confused ideas existed about it, the Mississippi was in 1672 relatively well known by the missionaries, who had acquired certain fairly precise notions regarding it from their contacts with the native populations of the Great Lakes. Its mouth still remained, however, a disquieting and undiscovered secret: might this river be at last the coveted waterway to the China Sea, the insubstantial stuff of the eternally disappointed dreams and quests of so many explorers?

Talon himself had not escaped the general obsession. In 1670, for example, he had instructed Daumont de Saint-Lusson to “seek out carefully . . . some communication” with the Southern Sea. The intendant had certainly heard of the Mississippi by then; but the additional information supplied during 1671 by Saint-Lusson and by the Relation of 1669–70 kindled a new hope in him. He resolved to send someone “to discover the Southern Sea, by way of the country of the Mashoutins [Mascoutens], and to go to the great river that they call Michissipi and that is thought to empty into the Sea of California.” For this ambitious scheme, Talon chose Louis Jolliet; shortly before sailing for France, in 1672, he suggested his candidate to Frontenac [see Buade], who accepted him. The mission entrusted to Jolliet was not so much to discover the Mississippi as to ascertain into what sea, the Gulf of Mexico or the “mer Vermeille,” this “beautiful river” flowed. Here was the riddle to be solved.

For the moment, the explorer was facing other problems. Talon had warned him that the state would not subsidize his expedition, any more than it had done for Saint-Lusson in 1670. To acquire funds, Jolliet formed a commercial society, the revenues of which would serve especially to meet the cost of his voyage of discovery. On 1 Oct. 1672 François de Chavigny* de La Chevrotière, Zacharie Jolliet, Jean Plattier, Pierre Moreau, Jacques Largillier*, Jean Thiberge (Téberge), and Louis Jolliet agreed, before Gilles Rageot, to “make together the journey to the Ottawa Indians, [and to] trade in furs with the Indians as advantageously [as possible].” On 3 October the partners attended to the last details of their preparations and settled certain matters with the notary Rageot. They probably left Quebec the next day, two days after the appointed date.

On 6 Dec. 1672 Jolliet arrived at Michilimackinac. There he delivered to Father Jacques Marquette a letter from Claude Dablon, the superior of the Jesuits in New France, ordering the missionary to join the expedition to the Southern Sea. In 1670 Marquette had been about to proceed via the Mississippi to the country of the Illinois, but the sudden worsening of relations between the Hurons, Ottawas, and Sioux had obliged him to cancel his plan. It was with enthusiasm and gratitude that he agreed to accompany Jolliet and to “seek . . . new nations that are unknown to us, to teach them to know our great God.” If Jolliet, the official envoy of the state, represented the economic and political aims of New France, Marquette represented its religious aspirations. Thus can be seen, felicitously combined in the 1673 expedition, the two great forces that launched the astonishing territorial expansion of the colony: the dictates of trade and the zeal for evangelism.

Did Jolliet spend the winter of 1672–73 at the Sainte-Marie falls, busy with his fur-trading, as it has been claimed? More probably he stayed at the Saint-Ignace mission at Michilimackinac, together with Marquette. On the one hand, he had to interrogate the Indians closely about the Mississippi and the peoples along its banks: Michilimackinac was the rallying-point of several nations, and Marquette was an expert in Indian languages. On the other hand Michilimackinac, the starting-point of the voyage of discovery, was the best place in which to complete the preparations for the expedition. An extract from the “Voyages du P. Jacques Marquette” (composed by Dablon) suggests this interpretation: “we obtained all the Information that we could from the savages who had frequented those regions; and we even traced out from their reports a Map of the whole of that New country; on it we indicated the rivers which we were to navigate, the names of the peoples and of the places through which we were to pass, the Course of the great River [Mississippi], and the: direction we were to follow when we reached it.” It is not impossible that Jolliet also stayed for some time at the Sainte-Marie falls; his presence would not be absolutely necessary since his partners and, particularly, his brother Zacharie were looking after his interests there, thus assuring to him the calm and the leisure necessary for the perfecting of his great plan.

Towards the middle of May 1673 the expedition set forth. It comprised seven men, in two canoes. In addition to Jolliet and Marquette, the group no doubt included some of Jolliet’s partners. Chavigny, however, who was at Fort Frontenac in July 1673, was not with them; we must also exclude Zacharie Jolliet, who seems to have remained at the Sainte-Marie falls to watch over his brother’s interests. The other partners (Largillier, Moreau, Thiberge, and Plattier) probably accompanied Louis Jolliet; the seventh person remains unidentified. In short, among the discoverers of the Mississippi, two only – Jolliet, the leader of the expedition, and Marquette – are known with certainty; for the others, one can, it is true, juggle with probabilities, but they will never yield more than hypotheses and conjectures.

The discoverers’ route, and more so the question of chronology, remain obscured by doubt, owing to the absence of a log-book. It seems almost certain, however, that from Michilimackinac the explorers headed westward, going along the north shore of Lake Michigan, then along the west shore of the Baie des Puants (Green Bay), as far as the Saint-François-Xavier mission (near De Pere, Wisconsin); from there they followed the Rivière aux Renards (Fox River) as far as the village of the Mascouten Indians (near Berlin, Wisconsin). After some 20 days of navigation, the expedition had just reached the limit of known territory. From the Mascoutens, the French learned of the existence – only three leagues away – of a tributary of the Mississippi; guided by two Indians, they made a “portage of half a league,” going from the Rivière aux Renards to the Rivière Meskousing (Wisconsin). On 15 June, after a journey of more than 500 miles, 118 of them along the Wisconsin, the canoes finally entered the Mississippi. An intense feeling of joy and triumph surged through the little band; but Jolliet was careful not to forget that the discovery of the Mississippi, however thrilling it might be, was only a stage in his glorious mission, and that he had promised Frontenac he would see the mouth of this river.

Pushing on with their advance along the Mississippi, the French gazed in wonderment at the new scenery, so different from anything they had known before; soon strange birds appeared, exotic plants, and formidable bison, in herds some of which numbered more than 400 animals. Of Indians, however, there was no sign. For eight or ten days the banks remained obstinately deserted, as far as the mouth of the Iowa, where at last the discoverers perceived their first village of Illinois Indians, the Peorias. They were received there with numerous gestures of friendship and welcome. Jolliet and his men took to their paddles once more, and pursued their journey, which was marked by two other important stages: they encountered first the Missouri and then the Ouabouskigou (Ohio), two stately rivers that flow into the Mississippi. The Indians were numerous in this region, and were as hospitable as the Peorias. When they got to the mouth of the Ohio the French had covered some 1,200 miles from Michilimackinac. Once again, as they got farther away from the Ohio, the landscape and climate changed rapidly; the Indians also became more distrustful, if not hostile; Marquette, although he spoke six native tongues, no longer managed to make himself understood. The little band finally stopped at the village of the Quapaws (Kappas), some 450 miles from the Ohio.

The Quapaws lived on the right bank of the Mississippi, a little this side of the present boundary of Arkansas and Louisiana, at lat. 34°40´N There Jolliet’s voyage was to end. The growing hostility of the Indians, the danger of falling soon into the hands of the Spaniards to whom the Arkansas nation were known, the certainty, acquired from the natives, that they were only 50 leagues from the sea – in reality they were more than 700 miles from it – and the fear of compromising the results of the expedition: all these factors induced Jolliet and his companions to turn back. In the second fortnight of July the canoes were launched against the current in the Mississippi; the return journey was carried out via the Illinois River, the Chicago portage, and Lake Michigan to the Baie des Esturgeons (Sturgeon Bay); thanks to a further portage, the canoeists passed into the Baie des Puants and went down to the Saint-François-Xavier mission, which they reached towards the middle of October.

Louis Jolliet had completed his mission. He had not seen the mouth of the Mississippi, but he had advanced sufficiently far south to acquire the certainty that the river emptied into the Gulf of Mexico. This news was a profound disappointment to all those who already believed that they possessed the passage to the China Sea; so much so that Jolliet’s very important contribution to what was then known of the geography of North America and to the territorial expansion of New France was not always appreciated at its true worth. But the obsession with the West was so firmly rooted and hopes were so keen that people immediately began once more to dream of another waterway, this time along one of the tributaries of the Mississippi.

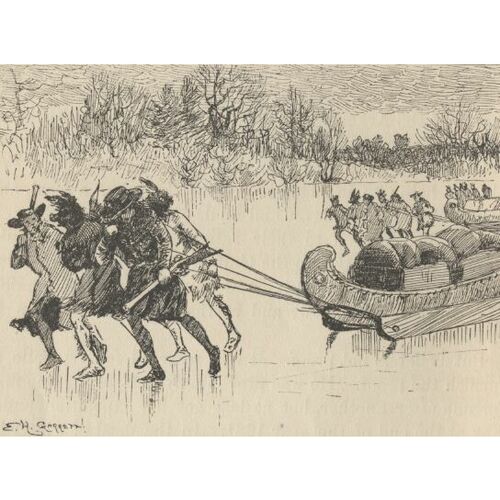

Jolliet spent the winter of 1673–74 at the Sainte-Marie falls, engaged in making copies of his log-book and of the map that he had drawn during the course of his expedition. Towards the end of May 1674, leaving replicas of these precious documents in the care of the Jesuits, he set out for Quebec. When he reached the Saint-Louis rapids, towards the end of June, his canoe was capsized: two Frenchmen and a little Illinois slave given to him when he went down the Mississippi were drowned; Jolliet, the sole survivor, was saved in the nick of time “after being four hours in the water”; the box that contained his log, his map, and his personal papers disappeared beneath the surface. The discoverer did not get off with this disaster: the copies of his log and map left at the Sainte-Marie falls were destroyed in a fire; and to complete the circle of misfortune Marquette’s diary has not come down to us. On the discovery of the Mississippi the historian therefore possesses only the information supplied from memory by Jolliet and documents based on second-hand knowledge, particularly Dablon’s account. Hence there are numerous gaps: who is to say, for instance, whether Jolliet officially took possession, in the name of France, of the territories discovered in 1673?

Back from the Mississippi, Jolliet began to think of settling down. On 1 Oct. 1675 he signed a marriage contract with Claire-Françoise Byssot, aged 19, the daughter of François Byssot de La Rivière and Marie Couillard; the latter had just married a second time (7 Sept. 1675), her new husband being Jacques de Lalande de Gayon. The religious ceremony was celebrated in the cathedral at Quebec, 7 October. In the following year Jolliet asked Colbert for permission to settle, with 20 men, in the land of the Illinois which he had discovered. The reply, dated 23 April 1677, was negative. The minister wrote: “we must increase the number of settlers before thinking of other lands.”

This refusal did not catch Jolliet unawares. From the time of his return from the Mississippi, he had resumed his commercial activity; but following upon his marriage with Claire Byssot – whose father had traded in the region of Sept-Îles where the family still had interests – Jolliet abandoned the hinterland for the north shore of the St. Lawrence River. On 23 April 1676 he joined the society consisting of Jacques de Lalande, his father-in-law, Marie Laurence, the widow of Eustache Lambert, and Denis Guyon; on 2 May the partners hired Guyon’s bark to meet the needs of the fur trade at Sept-Îles. Jolliet and Lalande, however, were not long in obtaining their own boat: on 2 Nov. 1676 they bought from Michel Leneuf* de La Vallière a ketch in which they made the trip to Sept-Îles the following spring.

Jolliet rapidly acquired a place among the merchants of consequence. On 20 Oct. 1676, for example, he was among the settlers assembled by Duchesneau to fix the price of beaver. Two years later, 26 Oct. 1678, he was one of the notables of the colony consulted by Frontenac about the traffic in intoxicating drink. Jolliet’s qualified opinion was the one adopted by Louis XIV in the ordinance of 24 May 1679, permitting traffic in spirits within the colony but forbidding it in the woods.

With Frontenac’s consent, in the spring of 1679, Josias Boisseau, the agent for the syndicate holding the Tadoussac trading concession, and Charles Aubert de La Chesnaye instructed Jolliet to “visit the nations and the territories of the king’s domain in this country.” By virtue of his commission the explorer was to go as far as Hudson Bay. It is difficult to state the exact object of this trip, but one may suppose that Jolliet assumed himself to have a double objective: to estimate the extent of English influence on the tribes in the Hudson basin, and perhaps to lay the foundations for a trade alliance with the Indians in the north. According to Father Crespieul*, who was working in the Lac Saint-Jean region in 1679, Jolliet’s role was to “establish the fur trade and the St. François Xavier mission at Nemiskau.” This testimony does not invalidate the two-fold hypothesis just formulated; it seems beyond question, indeed, that the task entrusted to Jolliet did not concern solely the fur-trading post – or the mission – at Nemiskau, which was only a stage in his expedition.

The 1679 voyage was not a voyage of discovery. After three fruitless attempts on the part of the French to reach Hudson Bay by sea (jean Bourdon in 1657), and by land (Claude Dablon and Gabriel Druillettes in 1661; Guillaume Couture* in 1661 and 1663), the Jesuit Charles Albanel, together with Paul Denys* de Saint-Simon and Sébastien Pennasca, had in fact reached the mouth of the Rivière Nemiskau in June 1672. The Jesuit repeated the journey in 1674. These precedents did not, it is true, lessen the terrible difficulties of the routes. In Albanel’s words, “There are 200 saults, or water-falls, and consequently 200 portages. . . . There are 400 rapids.”

On 13 April 1679 Jolliet embarked at Quebec with eight men, one of whom was his brother Zacharie. Two Indians, who acted as their guides, probably joined them on the way. The expedition apparently adopted the following itinerary: the Saguenay, Lac Saint-Jean, Rivière and Lac Mistassini, Rivière à la Marte (Marten) to Nemiskau, and Rivière Nemiskau, which flows into Rupert Bay, to the south of James Bay. The journey, in Jolliet’s estimation, covered 343 leagues, “because of the detours.” In the bay the explorer encountered some Englishmen, who welcomed him with a great show of politeness, and particularly Governor Charles Bayly, who gave him ship’s biscuits and flour for the return trip. Bayly had heard of Jolliet and of his discovery of the Mississippi; he congratulated the Canadian, assuring him that “the English have a high regard for discoverers.” After collecting all his information, and turning down a tempting offer from the governor, who invited him to enter the service of the English, Jolliet took leave of his hosts. He returned along the Rivière Nemiskau and the Rivière à la Marte, crossed Lac Mistassini and Lac Albanel, and, via the Rivière Temiscamie, went into the Rivière Peribonca, Lac Saint-Jean, and the Saguenay. On 25 October he regained Quebec.

During his voyage Jolliet had become convinced that in Hudson Bay the English were doing “the finest trade in Canada.” They “gathered in” beavers, “as many as they wanted,” and even hoped to “make this enterprise more extensive in the future.” The circle of their influence was growing larger all the time, and each spring the rivers of the Hudson basin brought down towards the English posts the heavily laden canoes of nations as numerous as they were distant. “There is no doubt that if the English are left in this bay [they] will make themselves masters of all the trade in Canada in less than six [ten?] years.” The Ottawas, indeed, who were the suppliers of the French, “do not hunt beaver, but go and seek them from the nations in the baie des Puants or from those in the neighbourhood of Lake Superior”; now it was to be feared that those nations would prefer to take their furs directly to the English, as certain of them had begun to do. And Jolliet discreetly requested His Majesty to “remove the English from this bay” or, at least, to “prevent them from establishing themselves any further, without driving them out or breaking with them.”

Jolliet was aware of the disastrous results that a drive by the English in Hudson Bay would have on the Tadoussac trading concession, and he also knew how much his own trade on the north shore was threatened. His interest in this region, which adjoined the king’s domain, was all the keener because on 10 March 1679 Intendant Duchesneau had granted him, in joint ownership with Jacques de Lalande, the Mingan islands and islets. Jolliet, however, lacked neither ambition nor optimism. In March 1680 he obtained Anticosti Island from Duchesneau. He proposed to set up, there and at Mingan, fishing-grounds for cod, seals, and whales, and “by this means to trade in this country and in the islands of America [West Indies].”

Because of this second grant of land, Jolliet incurred the fierce opposition of Josias Boisseau, the agent for the king’s domain, who had just quarrelled with Aubert de La Chesnaye, Jolliet’s uncle. The trade that Lalande and Jolliet were carrying on with the Indians of the Sept-Îles was thought to be doing harm to the tax-farmers of His Majesty’s domain. Counting on Frontenac’s support, Boisseau demanded in vain the cancellation of the Anticosti concession, as well as of certain fur-trading privileges granted by Duchesneau to Jolliet and his partners. The Crown’s agent made a lot of fuss, launched unfounded accusations, and indulged in such excesses of language and conduct that in the summer of 1681 he was relieved of his duties and recalled to France.

Despite Boisseau’s untimely complaints and extravagant behaviour, Jolliet continued his trading on the north shore. As early as 1680 or 1681 he had a dwelling on Anticosti, where he spent the summer months with his family and a few servants; in winter he lived at Quebec. Because of the scarcity of documents concerning him during the years 1680–93 – in 1682 his papers were burned in a fire – little is known of Jolliet’s activities between his voyages to Hudson Bay (1679) and to Labrador (1694). He exploited his fisheries at Mingan and Anticosti; but it is impossible to say whether he traded in the West Indies. During his frequent travels, Jolliet had completed a map of the St. Lawrence River and Gulf, which was sent to the minister in 1685. On that occasion Brisay* de Denonville requested for Jolliet the post of teacher of navigation. This reward was not accorded him. In 1690 the fleet commanded by Phips seized Jolliet’s bark, confiscated goods worth 10,000–12,000 livres, and took the discoverer’s wife and mother-in-law prisoners; two years later, two English ships sacked and burned his outposts at Mingan and Anticosti. Jolliet was ruined.

Jolliet had perhaps made a journey to Labrador in 1689, if we can believe a document dated 1693. He dreamed of going back there, but needed a subsidy, which the court seemed little inclined to grant him. Fortunately a Quebec merchant, François Viennay-Pachot, came to the rescue and agreed to cover the costs of the undertaking. Several explorers–Davis, Waymouth, Knight, Jean Bourdon, Chouart Des Groseilliers, and Radisson* – had already sailed along the coasts of Labrador, but none had produced a tolerably exact account of them, or even a map. Jolliet was to be the first to reveal the secret of this region that extended from the Saint John River (15 miles west of Mingan) to the present Zoar, situated at lat. 56°8´N.

On 28 April 1694, at Quebec, Jolliet boarded a vessel armed with 6 swivel-guns and 14 cannon, belonging to Pachot; the crew comprised 18 persons, one of whom was a Recollet. They dropped anchor first at Mingan, where Jolliet stayed for more than a month to traffic in furs and to reconstruct the buildings burned down by the English. On 9 June they set sail for Labrador. Jolliet sailed along the coast, which he described and mapped out systematically, doing a little trading when the opportunity presented itself. Shortly after 9 July the ship passed the Pointe du Détour (Cap Charles), and entered unknown waters. Continuing his slow advance, Jolliet charted the coastline and described the Eskimos with whom he made contact. When he drew level with Zoar, the explorer decided to turn back. The season was well advanced, and the ship, fitted with poor rigging, would not have withstood the heavy weather of autumn; besides, trade with the few Eskimos along the coast could not “pay what the vessel cost every day”; finally, the ship was carrying salt “which had to be used for cod.” On 15 August Jolliet started on the way home. He reached Quebec around the middle of October, after having fished, and after having probably stopped at Mingan to take on board his wife and children, who had spent the summer there.

Jolliet hastened to give a final form to his travel log. This relatively extensive document contains, in addition to a description of the Labrador coasts and their inhabitants, 16 cartographic sketches. It is the first account of the shoreline between Cap Charles and Zoar, hence its historical importance; moreover, it was in 1694 the most complete and precise portrayal of the Eskimos so far made. As for the territories visited, Jolliet found the soil barren and the inhabitants few in number; he noted the rapid disappearance of cod as soon as one proceeded northward; the only trade possible with the Eskimos was in whale oil and seal oil, but even then it would be necessary to count on cod “to cover part of the costs.” Jolliet was not put off because of that: he applied for the privilege – which he was not to receive – of trafficking alone, for 20 years, with the Eskimos of Labrador.

In the autumn of 1695, when the season was well advanced and navigation in the river and gulf dangerous, he was selected by the governor and the intendant to pilot the Charente: he was “perhaps the only man in this country, according to Frontenac, capable of performing this work properly.” For this task Jolliet received 600 livres. He spent the winter in France, and returned to Quebec before 13 June 1696 with the promise of his appointment – confirmed 30 April 1697 – to the office of hydrographer. In a document of 1692 he had already been given the title of hydrography master: was this a lapsus, or was Jolliet teaching hydrography at the Jesuit college, without holding the post officially? Be that as it may, Jolliet and the maps that he was able to make to render navigation in the river and gulf safe were often mentioned during these years. One of the maps, dated 1698, has come down to us.

On 30 April 1697 Jolliet had received from Frontenac and Bochart* de Champigny a small fief on the Rivière des Etchemins, which he did not have time to develop. In winter he taught at the Jesuit college; in summer he probably lived on Anticosti Island or at Mingan. Unfortunately the last three years of his life are shrouded in uncertainty. Was it on his lands on the north shore that he died in the summer of 1700, in circumstances that have not been revealed? Nothing is known of this, and despite active research his burial place has not yet been discovered.

Thus ended, between 4 May and 15 Sept. 1700, the remarkable career of this explorer; his broad education, his culture, the diversity of his talents as much as his courage and ambition, made of him one of the greatest and most illustrious sons of his country. Born in New France, formed in its institutions, Jolliet attained international fame during his lifetime: in France, Spain, Italy, Holland, Germany, England, works extolled his name and the discovery of the Mississippi. Beyond all doubt, the Canadian Louis Jolliet is one of the most genuine and most impressive examples of the heroes produced by New France.

Acte de baptême de Louis Jolliet (21 sept. 1645), APQ Rapport, 1924–25, 198. Acte de mariage de Louis Jolliet et de Claire-Françoise Bissot (Québec, 7 oct. 1675), APQ Rapport, 1924–25, 224. AJQ, Greffe de Romain Becquet, 7 mai 1666; 1er oct. 1675; 9 mai 1679; 16 avril 1680; Greffe de Pierre Duquet, 2 nov. 1676; 9 févr. 1679; Greffe de François Genaple, 14 mars 1680; Greffe de Gilles Rageot, 21 avril 1669; 1er oct. 1672; 3 oct. 1672; 23 avril 1676; 2 mai 1676; 4 déc. 1676; 17 avril 1680. APQ, Ins. cons. souv., II, 3. Contrat de mariage de Louis Jolliet et de Claire Bissot (1er octobre 1675), APQ Rapport, 1924–25, 240. Correspondance de Frontenac, APQ Rapport, 1926-27, 1927–28 et 1928–29, passim. Correspondance de Talon, APQ Rapport, 1930–31, passim. [Claude Dablon], “Voyages du P. Jacques Marquette, 1673-75,” in JR (Thwaites), LIX, 85–211; ibid., passim. JJ (Laverdière et Casgrain), 330, 345. [Louis Jolliet], “Journal de Louis Jolliet allant à la descouverte de Labrador, 1694,” éd. Jean Delanglez, in APQ Rapport, 1943–44, 147–206. Jug. et délib., passim. Ord. comm. (P.-G. Roy), I, 322f. P.-G. Roy, Inventaire de pièces sur la côte de Labrador conservées aux Archives de la Province de Québec (2v., Québec, 1940–2), I, 3–9. Recensement de 1666. Delanglez, Jolliet. Ernest Gagnon, Louis Jolliet, découvreur du Mississipi et du pays des Illinois, premier seigneur de l’île d’Anticosti (Montréal, 1946); “Où est mort Louis Jolliet?” BRH, VIII (1902), 277–79. Godbout, “Nos ancêtres,” APQ Rapport, 1951–53, 459. Amedée-E. Gosselin, “Jean Jolliet et ses enfants,” RSCT, 3rd ser., XIV (1920), sect.i, 65–81. Lionel Groulx, Notre grande aventure: l’empire français en Amérique du Nord (1535–1760) (Montréal et Paris [1958]), 139–74. Pierre Margry, “Louis Jolliet,” RC, VIII (1871), 930–42; IX (1872), 61–72, 121–38, 205–19. Adrien Pouliot et T.-Edmond Giroux, “Où est né Louis Jolliet?” BRH, LI (1945), 344–46, 359–63, 374.

Cite This Article

André Vachon, “JOLLIET, LOUIS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 1, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jolliet_louis_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jolliet_louis_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | André Vachon |

| Title of Article: | JOLLIET, LOUIS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | April 1, 2025 |