Source: Link

ALBANEL, CHARLES, priest, Jesuit, missionary, and explorer; b. 1616 (or 1613) in Auvergne; d. 11 Jan. 1696 at Sault Ste. Marie.

It has been claimed that he was born of English parents residing in France, but this opinion has no other basis than an incorrect reading of a text by Thomas Gorst, storekeeper and secretary to the governor of Hudson Bay, Charles Bayly. Of Albanel’s youth nothing is known, except that he had finished two years of philosophical studies when he entered the Jesuit noviciate of the province of Toulouse 16 Sept. 1633. From 1635 on he taught, in succession, grammar, the humanities, and rhetoric at the colleges of Quercy (in Cahors), Carcassonne, Mauriac, and Aurillac. In 1636–37 he taught the second form of secondary school at Montpellier, and the following year he did a third year of philosophy at Billom. After his four years of theology at Tournon, he had to wait until 1648–49 to finish his religious training with the third year. It was in March of 1649 that he sailed for Quebec, where his arrival on 23 August was noted in the Journal des Jésuites. A month after landing at Quebec he left for Ville-Marie (Montreal), where his name appeared the following year in the little baptismal register.

During the next ten years he went to Tadoussac nearly every winter, returning to Quebec in the spring or summer. Dates allow us to chart his movements. On 22 Oct. 1650 he set out for Tadoussac with the intention of spending the winter among the Montagnais or Lower Algonkins, and returned on 22 April of the following year. On 2 May 1651 he sailed aboard a bark for Tadoussac and Gaspé. After a difficult winter with the nomadic Montagnais, he was back at Quebec in time to leave again on 4 May 1652 on a frigate with Father de Quen. He returned 10 April 1653 with Louis Couillard de Lespinay. On 13 Nov. 1653 the Journal des Jésuites mentions that the Quebec fathers received letters from him brought by M. de Lespinay. On 24 Feb. 1654 we learn that he was spending his fourth winter among the Indians. Two years later, according to the Journal, M. de Lespinay brought news of him from Tadoussac on 31 October, and on 17 November the Indian Kahikohan passed on news of him from Le Bic. On 3 Feb. 1657 he left this place, and returned by foot along the south shore in company with Couillard and four Frenchmen; after a difficult trip they reached Quebec on 8 March. Between the time he left Quebec, 13 May 1658, and his return on 8 August, he worked at the Sainte-Croix mission near Tadoussac, where he had gone at the same time as Father Du Peron, Brother Nicolas Charton, and two Frenchmen. In 1659 he went again to Tadoussac. He left on 10 May and returned 31 August on Lespinay’s vessel, which was coming back from hunting seals. The following winter he was again at Tadoussac. He had left Quebec 21 Nov. 1659 with four Frenchmen and he returned in April 1660.

On 8 July 1660 he went to Trois-Rivières with Governor Voyer* d’Argenson, and their boat was attacked by the Iroquois during their return trip. On 14 September of the same year he sailed as far as Montreal on his way to spend the winter among the Bœuf Nation. For a few years the Journal des Jésuites says nothing about Father Albanel, but we know that he had settled down at Cap-de-la-Madeleine, where he was the parish priest and superior. Father Frémin replaced him in these charges on 17 Aug. 1665, but Albanel retained the main responsibility for the Montagnais or Algonkin missions, which at that time were being ravaged by the scourge of alcohol. The Journal des Jésuites mentions his departure from Trois-Rivières on 16 Nov. 1665 to go to serve as priest for a brief period at Fort Saint-Louis (Chambly) in place of Father Du Peron, who had died six days earlier. By 2 December he was at Trois-Rivières again, while waiting to go farther inland, probably to the upper Saint-Maurice River. In February 1666, shortly after being appointed parish priest at Fort Saint-Louis, he was accused by the governor, Rémy de Courcelle, of having dissuaded the Indians from taking part in his war party that winter. Intendant Talon succeeded in persuading Courcelle to drop an accusation that was as surprising as it was unjustified. On 14 October of the same year Father Albanel accompanied the Carignan-Salières regiment as chaplain, along with Father Raffeix*, in a campaign against the Iroquois. Prouville de Tracy and his soldiers were very pleased with him. In 1668–69 he spent a year at the Sillery mission; that same winter we find him again among the wandering tribes at the Sainte-Croix mission. He has left us two letters in which he has described his work during this period. In the course of his travels he visited the Papinachois Indians. On 15 June 1670 he left Tadoussac on a mission to evangelize the Oumamiois (Bersiamites), after obtaining two French companions from Nicolas Juchereau de Saint-Denis.

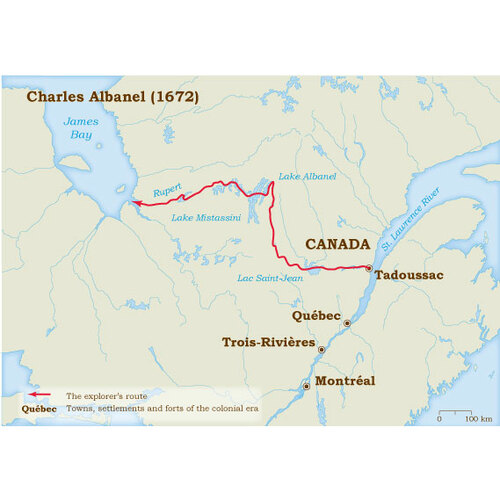

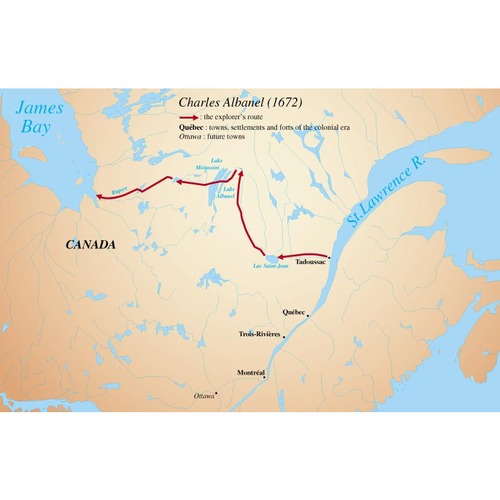

In 1671 Intendant Talon decided to send “two resolute men” to Hudson Bay. “Accordingly,” Father Dablon tells us, “we fixed our choice on Father Charles Albanel, former missionary to Tadoussac, since he has had much intercourse with the Savages who possess a knowledge of that sea, who alone are able to act as guides over those hitherto unknown ways.” The purpose of Albanel’s voyage (1671–72) was to discover whether the Northern Sea was indeed Hudson Bay and to verify the presence there of Europeans who were said to be French. The persons concerned were in fact Chouart Des Groseilliers and Radisson*, who had gone over to the service of the English.

Father Albanel was induced to make his trips to the Northern Sea because New France had long felt the fascination of a region that was generally considered as a natural frontier yet to be explored, as well as a rich territory where the Indians were for the missionaries persons to be converted and for the traders valuable allies in the trade in pelts. It was already known that Hudson Bay served as a passage-way for the English explorers in their search for the Western Sea. The French too had some hypotheses to verify concerning this passage. Thus, Jean Bourdon had made a first attempt by sea in 1657 but had to turn back at the 55th parallel. In the same year possession was taken of the basin of the Northern Sea in the name of the king of France. In 1661 these attempts were complemented by the land expedition carried out on Governor Argenson’s order. The group, to which belonged the Jesuits Dablon and Druillettes, had reached a point a little beyond the watershed. This was only a postponement, for it was realized in New France that the country that held this region would at the same time be in possession of the entrance to the Western Sea and the inexhaustible wealth of beaver skins.

Father Albanel left Quebec 6 Aug. 1671 for Tadoussac, where he arranged to meet his two companions, Paul Denys* de Saint-Simon and a certain Sébastien Provencher. Upon his arrival on 8 August he secured the services of Montagnais guides. The group was at Chicoutimi on 26 August and left there on 29 August, reaching the far end of the lake on 7 September. Ten days later Albanel met five canoes bearing Attikamegue and Mistassini Indians and learned of the presence in the Bay of two English ships that were trading there. He then decided it would be well to have passports, which he sent messengers to obtain from the governor, the intendant, and the bishop in Quebec. The messengers did not return until 10 October, too late for the party to undertake the rest of the trip immediately. It was decided to spend the winter where they were, and Father Albanel took advantage of this to evangelize the Mistassinis and to baptize their children. The season was on the whole a hard one, according to Father Albanel, who thought that it was the most severe “of the ten winters [that he had spent] in the woods with the Indians.” At that time he was only 55, even though Thomas Gorst considered him to be “a little old man.” His guides abandoned him, and it was only his diplomacy that enabled him to find others.

On 1 June 1672 there was a new attempt, with 3 canoes bearing 3 Frenchmen and 16 Indians. On 9 June they were at the divide, that is to say, about the point reached by Father Dablon in 1661. The Mistassinis wanted to prevent them from going any farther. But Father Albanel succeeded with gifts and fair words in convincing them that the French would protect them against their enemies the Iroquois. On 18 June the expedition reached Lake Mistassini, and then Lake Nemiskau on 25 June, whence they went down the Rupert River, reaching its mouth on 28 June. There they found an English ship and two deserted houses: before leaving for England, everyone had gone hunting. Father Albanel took advantage of the absence of the English party to make the acquaintance of the Indians, to teach them and baptize some of them. After a few days sailing and exploring in James Bay, Albanel entrusted a letter for Radisson to the Indians and set out on the return trip on 6 July, without meeting any Englishmen or French deserters. Three days later the group raised the arms of the king of France at Lake Nemiskau. On 23 July the travellers were at Lake St. John, then on 1 August at Chicoutimi, where they were being awaited by the captain who was to take them to Tadoussac and thence to Quebec.

In the account of his trip Albanel reported that he had baptized 200 people, 100 adults and as many children. He had identified Hudson Bay, seen an English ship, and established firm ties with the Indians. But he had met no whites. The journey, he related, entailed many difficulties: an 880-league trip, 200 portages, falls, and dangerous passages, distrust on the part of the Indians, and so on. Finally he credited himself with the idea of such an undertaking. “Up till that time it had been felt that such a voyage was beyond the possibilities of the French, who, having already attempted it three times and having been unable to overcome the obstacles attendant upon it, despairing of success, had been obliged to give it up. What seems impossible becomes easy when it is pleasing to God. The leadership of this expedition was rightfully mine, after 18 years of attempts that I had made, and I had quite tangible proofs that God was reserving for me its successful completion.”

“Fine beginnings,” he concluded, in a way that forecast a new attempt before long. In fact, in a letter to Colbert (13 Nov. 1673), Frontenac [see Buade], tells us: “I have utilized the zeal shown by Father Albanel, a Jesuit, for undertaking a mission to those regions in order to try to dissuade the Indians, among whom he is highly trusted, from following this route for trade with the English. . . . The aforementioned Father Albanel is to sound out Des Groseilliers, if he meets him, and to try to find out whether he can bring him back to our side.”

Bearing a letter, dated 8 Oct. 1673, from Frontenac to Governor Bayly, Albanel left for Tadoussac, and by 13 Jan. 1674 he set off for the Northern Sea. On the way a burden fell on his back, immobilized him, and forced him to spend the winter in the region of Lake St. John. There he was visited by Father Crespieul*, in the month of January, then on 2 February and again on 3 March. The rest of the voyage is known to us only through English sources. Oldmixon, who summarizes Gorst, tells us that Albanel reached the Rupert River 30 Aug. 1674, along with a young Indian and a Frenchman born of English parents, probably Des Groseilliers’s nephew. Albanel was carrying a letter for Des Groseilliers. Gorst claims that Albanel sought refuge with him in order to escape bad treatment from the Indians and in order not to have to make the return trip, which was so difficult. Despite Frontenac’s letter, which was on the whole friendly, the English in Hudson Bay rather treated Albanel as a traitor, an enemy who had come to lure the Indians away from their alliance with them, in order to win them over to friendship and trade with the French. Albanel and his companion were detained by Bayly and then sent to England, after receiving hospitality, clothes, and money. In London Albanel is supposed to have obtained a letter exonerating him which he could deliver to his superiors, who he was afraid would accuse him of deserting the missions. Returning to France, the Jesuit embarked again for Canada and landed at Quebec 22 July 1676. He refused to talk about his voyage while on the ship, and later his companion promised to answer no questions until after the priest’s death. Thus posterity was for ever deprived of important and valuable detailed information about this expedition.

Three days after his return to Quebec, a combination of circumstances led to his being appointed to the missions in the hinterland. He became superior at Sault Ste. Marie, even though he was “old and worn out,” the author of the 1679 Relation informs us. His extraordinary talent for languages was responsible at that time for his beginning again a new missionary experience. He spent the rest of his life in these regions. Appointed superior of the Saint-François-Xavier missions (Baie des Puants, now De Pere, Wisconsin) on 25 July 1676, he was succeeded in this post by Father Henri Nouvel* in 1679. In the year of his appointment “he replaced the original chapel by an attractive church,” Gérard Malchelosse informs us. In 1683, wrote Father Beschefer*, Father Albanel, though aged and trembling, had for some years been sharing with Father Louis André* the whole responsibility for the Sault Ste. Marie mission. On 11 Jan. 1696 he died there at 80 years of age.

ACSM, f. 802. Découvertes et établissements des Français (Margry), I, 92–96. JR (Thwaites), LIII, 58–92; LVI, 148–217. BRH, IX (1903), 216f.; XVIII (1912), 160, 192; XXII (1916), 226; XXV (1919), 111. N. M. Crouse, Contributions of the Canadian Jesuits to the geographical knowledge of New France (Ithaca, N.Y., 1924). HBRS, XXI (Rich). Séraphin Marion, Relations des voyageurs français en Nouvelle-France au XVIIe siècle (Paris, 1923), 168–78. Jacques Rousseau, “Les voyages du père Albanel au lac Mistassini et à la Baie James,” RHAF, III (1949–50), 556–86. See also the bibliography for Thomas Gorst.

Cite This Article

Georges-Émile Giguère, “ALBANEL, CHARLES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/albanel_charles_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/albanel_charles_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | Georges-Émile Giguère |

| Title of Article: | ALBANEL, CHARLES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 2014 |

| Access Date: | December 30, 2025 |