JOHNSON, Sir WILLIAM, superintendent of northern Indians; b. c. 1715, eldest son of Christopher Johnson of Smithtown (near Dunshaughlin, Republic of Ireland) and Anne Warren, sister of Vice-Admiral Sir Peter Warren*; d. 11 July 1774 at Johnson Hall (Johnstown, N.Y.).

In 1736 William Johnson began acting as agent for Peter Warren, receiving rent from Warren’s Irish tenants. Early in 1738 Johnson came to America to oversee an estate that Warren had acquired near Fort Hunter, in the Mohawk valley of New York. He arrived at a propitious moment, since the struggle between France and Britain for hegemony in eastern North America came to a climax during his lifetime. To this conflict Johnson gave the remainder of his life, and through it he built his fortune, one of the largest in colonial America.

With much capital supplied by his naval uncle, Johnson became within a decade of his arrival the most substantial businessman on the Mohawk. Employing white indentured labourers and black slaves, he established a 200-acre farm on the south bank of the river; in 1739 he bought an 815-acre tract on the north side with access to the King’s Road, which reached as far west as the Oneida Carrying Place (near Oneida Lake). Through an agent he began trading in imported English goods to the Indian settlement of Oquaga (near Binghamton). He also contracted with farmers for their surpluses of wheat and peas. By 1743 he had opened trade to Oswego (Chouaguen), the principal fur-trading post of British America. His shop on the King’s Road served as the supply centre for all his dealings, and he thus cut into the long-established monopoly of the Dutch houses in Albany. He also shipped his own goods to New York City, where they were sold or transported either to the West Indies or to London.

Such business skill and success inevitably led to involvement in public affairs. In April 1745 he was made a justice of the peace for Albany County. Between 1745 and 1751 he was colonel of the Six Nations Indians, a responsibility formerly held in commission by several Albany fur-merchants. His influence with the Six Nations, especially his neighbours the Mohawks, soared, for he had ready access to provincial funds to pay the Indians regularly for their services. During the War of the Austrian Succession he attempted to organize Indian scouting and raiding parties on the frontier in support of a planned attack on Fort Saint-Frédéric (near Crown Point, N.Y.), but he was not particularly successful since the Six Nations generally remained committed to neutrality. In February 1748 he was made colonel of the 14 militia companies on the New York frontier, and in May colonel of the militia regiment for the city and county of Albany, positions which he held for the rest of his life and which opened great opportunities for patronage. He was appointed to the New York Council in April 1750, but he rarely attended its sittings.

Most of his time during the interval of relative peace from 1748 to 1754 he spent in pursuit of his private fortune. In April 1746 he had won the contract to supply the garrison at Oswego, and by 1751 he had provided goods and services amounting to £7,773, New York currency. Though he claimed a loss of about five per cent on the contract, he clearly profited from it by collecting duties at Oswego and by padding his accounts. With the approach of the Seven Years’ War he once again became deeply involved in provincial affairs. A member of the New York delegation to the Albany Congress in June and July 1754, he advocated increased expenditure for garrisons among the Indians at strategic points and called for a regular policy of paying Indians for their services. He wanted young men to be sent among the native people as interpreters, schoolmasters, and catechists. The congress came to no agreement, but a month later the Board of Trade decided on its own initiative to create a regular Indian administration financed by parliament. In April 1755 Edward Braddock, commander-in-chief in North America, selected Johnson to manage relations with the Six Nations and their dependent tribes. As he explained to the Duke of Newcastle, Johnson was “a person particularly qualify’d for it by his great influence with those Indians.” In February 1756 Johnson received a royal commission as “Colonel of . . . the Six united Nations of Indians, & their Confederates, in the Northern Parts of North America” and “Sole Agent and Superintendant of the said Indians.”

In April 1755 Braddock had also made Johnson commander, with the provincial commission of major-general, of an expedition to take Fort Saint-Frédéric. The campaign, which called as well for a force under Braddock to seize Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh, Pa) and one under William Shirley to take Fort Niagara (near Youngstown, N.Y.), was a dismal failure except for one engagement in which Johnson was involved early in September. At Lake George (Lac Saint-Sacrement) with part of his force of some 300 Indians headed by Theyanoguin* and 3,000 Americans, Johnson learned that a strong French column under Jean-Armand Dieskau* was moving towards Fort Edward, where the rest of his men were encamped. Johnson’s relief detachment was ambushed and the survivors hotly pursued by some French regulars, who rashly attempted to take the hastily fortified position at Lake George by storm. They were cut to pieces by the Americans, and Dieskau was wounded and captured. Johnson, himself wounded early in the attack, played little part in the battle but was given credit for its outcome. When he visited New York City at the end of the year, he was greeted as a hero, and the king created him a baronet. In 1757 parliament made him a gift of £5,000. Never was such an insignificant encounter so generously rewarded.

Johnson had resigned his military commission late in 1755, and thereafter his duties largely concerned Indian affairs. With Indian raids disturbing the Pennsylvania frontier, he was given permission to appoint a deputy there, George Croghan. Their attempts to enlist Indians in the British cause were unrewarding during the early years of the war, which were marked by singular British setbacks. Fort Bull (east of Oneida Lake) was overrun by forces under Gaspard-Joseph Chaussegros de Léry in March 1756. Oswego fell to Montcalm* that August and was destroyed. Fort William Henry (also known as Fort George, now Lake George) surrendered in August 1757, and German Flats (near the mouth of West Canada Creek) was attacked in November. In 1758 a huge force under James Abercromby failed to take Fort Carillon (Ticonderoga). The Indians largely remained neutral, and Johnson’s prestige, despite his numerous conferences with them, waned.

This situation was altered by the string of victories beginning with Amherst’s capture of Louisbourg, Île Royale (Cape Breton Island), in 1758 and culminating in the fall of Fort Niagara and Quebec. The successful attack on Niagara was an important military encounter for Johnson. Undetected by Pierre Pouchot*’s garrison, the British under John Prideaux concentrated at Niagara a force of about 3,300 regular and provincial troops early in July 1759. Johnson, as second in command, was responsible for the contingent of some 940 Indians. After less than two weeks of siege Prideaux was killed and Johnson assumed command. Five days later a French force under François-Marie Le Marchand* de Lignery, coming from the Ohio valley, approached to relieve the garrison. Johnson sprang an ambush so successfully that the enemy not slain or taken prisoner fled in panic. The next day, 25 July, the fort surrendered. With it went control of the strategically important portage; the main artery of the French fur trade had been cut.

In the final campaign of the war Johnson accompanied Amherst to Montreal in 1760. Although he started out with almost 700 Indians, Johnson led only 185 into the city, the rest having departed following the surrender of Fort Lévis (east of Prescott, Ont.). After a few days in Montreal, he appointed Christian Daniel Claus his resident deputy there and returned to the Mohawk valley.

Indian affairs acquired a new dimension and a new importance with the fall of Canada. Problems that had necessarily been dealt with piecemeal during the war now demanded broader approaches. Johnson’s policy, never spelled out in much detail despite various promptings from London, had four main points. The purchase of Indian lands should be controlled at a pace determined by the tribes’ willingness to sell. Trade should be restricted to designated posts and be carried on at fixed prices by traders required to post bond and licensed annually. To oversee the administration the superintendent would have need not only of deputies but also of commissary-inspectors, interpreters, and gunsmiths. To finance its operation he suggested a tariff on rum.

What happened was rather different. Though much of the administration was established it was paid for by parliament. Prices were never fixed, and traders were never wholly restricted by bonds, licences, or designated trading posts. Moreover, the governors of Canada, through which most of the fur trade passed, issued their own licences and took measures to control the trade without reference to Johnson or his deputy there. Worse still for Johnson was the fact that since his regulations never had legal force he was powerless to punish those who ignored his sanctions. From 1768, when London abandoned its centralized control of Indian affairs, each colony was left to develop as best it could its relations with the Indians on its frontier. This decision coincided with another the home authorities made for economy, to withdraw garrisons from the western posts. Thereafter Johnson ought to have had close dealings with the New York government, yet he was never consulted about Indian affairs. Nor did he bother to build a party of support in the council or the assembly.

As superintendent he was under the orders of the commander-in-chief in North America, until 1763 Amherst, with whom Johnson greatly differed in opinion. Since the real instrument of British power in America was the army, Amherst’s views carried the day. Whereas Johnson wished to encourage the supply of arms and ammunition to the Indians, Amherst, who put little value on their services, wished to restrict it. Whereas Johnson always worked diplomatically for an accommodation with the Indians, Amherst wished to deal forcefully with any tribe that opposed British arms. The 1763–64 Indian uprising would doubtless have resulted in a serious clash between Johnson and the commander-in-chief had not Amherst, at the height of the crisis, been given leave to return home to England. His successor, Gage, reverted to the policy Lord Loudoun and Abercromby had followed; he issued no direct orders and left the superintendent free to work out details. In this way peace was made with Pontiac* and his allies, and little retribution was taken for the deaths of nearly 400 soldiers and perhaps 2,000 settlers.

After 1760 Johnson conferred frequently with the Indians, settling grievances and renewing covenants of friendship with them on behalf of the crown. In 1766 he met with Pontiac at Oswego, and in 1768 at Fort Stanwix (Rome, N.Y.) he settled the new boundary line for Indian lands with Kaieñˀkwaahtoñ and other leaders. Thereafter he confined himself largely to meeting the Six Nations at his home. It was in the midst of one such conference in July 1774 that he fell ill “with a fainting and suffocation which . . . carried him off in two hours.” Gage remarked: “The king has lost a faithful, intelligent servant, of consummate knowledge in Indian affairs, who could be very ill spared at this juncture, and his friends an upright, worthy and respectable man, who merited their esteem.” This verdict has generally been endorsed by historians and biographers.

In fact Johnson served himself at least as well as he served his king. From April 1755 until his death some £146,546 came into his hands as superintendent, an annual average of £7,700. From it he received his salary, as well as salaries for his son John* and sons-in-law Guy Johnson and Daniel Claus. He arranged for the crown to rent his store and pay his storekeeper’s wages and he charged the crown two and one-half per cent commission on all goods he supplied to the Indians as superintendent. He had the crown build a school for the Indians and pay a schoolmaster’s salary, though he took credit for both. Perhaps the principal item in value furnished to the Indians was rum. The same accounts charged the crown with the cost of burying Indians killed while drunk. He never submitted vouchers, only the bald accounts, which, though unaudited, were always paid.

There was also considerable conflict of interest in Johnson’s dealings in Indian lands. Publicly he represented a policy to prevent the despoliation of such lands, yet privately he arranged for their purchase by himself and by others. These tracts were without value to whites unless settled and cultivated, and by that process the Indian way of life, in which hunting played an important part, was destroyed. As superintendent, Johnson negotiated the land deal between the prospective purchaser and the Indians, and at least from 1771 he had the permission of the Six Nations to set the price of their land.

The territory he acquired for himself was not insignificant. He accepted a 130,000-acre grant from the Mohawks of Canajoharie (near Little Falls, N.Y.). For £300, New York currency, he bought about 100,000 acres on the Charlotte Creek, a tributary of the Susquehanna River though as a result of boundary limits set by the Fort Stanwix agreement of 1768 he was obliged to abandon his purchase. In 1765, less than three months after a treaty had been concluded with Pontiac, designed in part to allay Indian fears for their land, Johnson purchased some 40,000 acres from the Oneidas. In all this he acted no differently from dozens of other speculators in Indian lands. He was distinguished only by the great advantages he possessed through his office and through his long intimacy with the Indians. He was indeed one of their principal exploiters; his actions speak louder than any words of his. He was a typical imperial servant, in an area where he had few competitors able to match his intelligence and interest – an almost unbeatable combination in the 18th century.

Johnson was a man of some intellectual curiosity, and he amassed a substantial library of books and periodicals. On occasion he purchased scientific instruments. In January 1769 he was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society, but he never went to its meetings. He also belonged to the Society for the Promotion of Arts and Agriculture and to the board of trustees of Queen’s College (Rutgers University, New Brunswick, N.J.), though he never attended its sessions.

There is no evidence that Johnson ever married. In his will he acknowledged as his wife Catherine Weissenberg (Wisenberg), an indentured servant who had escaped from her New York City owner. He took her in in 1739, and by the time of her death in April 1759 they had had three children. He is thought to have cohabited with many Indian women, but his most important liaison, for personal and political reasons, was with Mary Brant [KoñwatsiÃtsiaiéñni]. Eight of their children survived him.

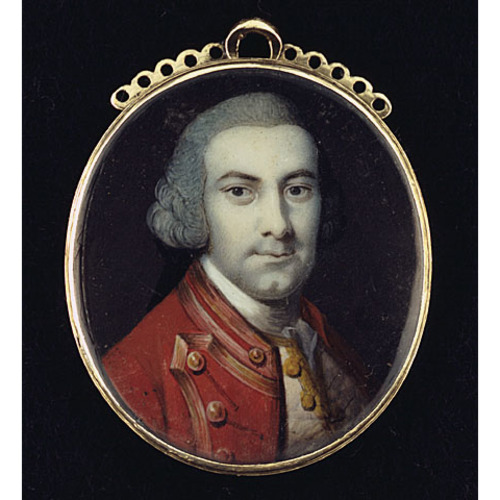

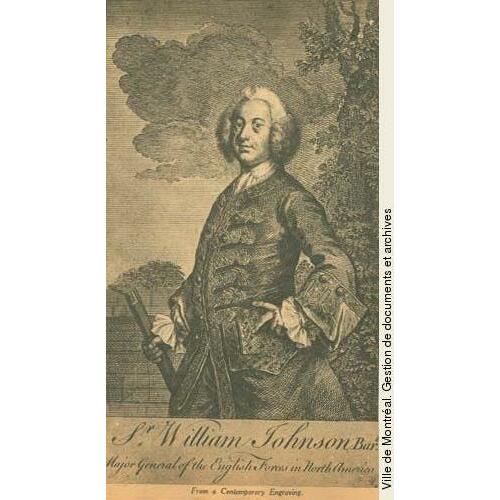

The earliest portrait of Johnson, completed about 1751, is attributed to John Wollaston and is in the Albany Institute of History and Art (Albany, N.Y.). There is a miniature in the PAC. The N.Y. Hist. Soc. holds an 1837 copy by Edward L. Mooney of a portrait done in 1763 by Thomas McIlworth. A fourth was painted in 1772 or 1773 by Matthew Pratt and hangs in Johnson Hall, the site also of a celebrated bronze statue.

[Johnson has appeared in much fiction, and in the opinion of the noted Johnson scholar Milton W. Hamilton, it was the novels of Robert William Chambers that “gave many Americans their only conception of Sir William.” Johnson has been the subject of several biographies, none adequate. Errors in the earliest, W. L. [and W. L.] Stone, The life and times of Sir William Johnson, bart. (2v., Albany, N.Y., 1865), have often been repeated. The most recent, M. W. Hamilton, Sir William Johnson, colonial American, 1715–1763 (Port Washington, N.Y., and London, 1976), adds useful detail but misunderstands the central feature of Johnson’s career, his relations with the Indians.

Johnson’s role as an Indian agent has figured prominently in numerous monographs, the best of which are unpublished. Dissertations include D. A. Armour, “The merchants of Albany, New York, 1686–1760” (phd thesis, Northwestern University, Evanston, Ill., 1965), especially chap.ix; C. R. Canedy, “An entrepreneurial history of the New York frontier, 1739–1776” (phd thesis, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, 1967), especially chaps.ii–iii; E. P. Dugan, “Sir William Johnson’s land policy (1739–1770)” (ma thesis, Colgate University, Hamilton, N.Y., 1953); W. S. Dunn, “Western commerce, 1760–1774” (phd thesis, University of Wisconsin, Madison, 1971), especially chap.v; E. R. Fingerhut, “Assimilation of immigrants on the frontier of New York, 1764–1776” (phd thesis, Columbia University, New York, 1962); E. M. Fox, “William Johnson’s early career as a frontier landlord and trader” (ma thesis, Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y., 1945); F. T. Inouye, “Sir William Johnson and the administration of the Northern Indian Department” (phd thesis, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, 1951); D. S. McKeith, “The inadequacy of men and measures in English imperial history: Sir William Johnson and the New York politicians, a case study” (phd thesis, Syracuse University, Syracuse, N.Y., 1971); Peter Marshall, “Imperial regulation of American Indian affairs, 1763–1774” (phd thesis, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., 1959).

Most of Johnson’s manuscripts have been published in Johnson papers (Sullivan et al.), the last editor of which was M. W. Hamilton, who has also written a number of short articles on aspects of Johnson’s life and on Johnsoniana. Other collections with many Johnson letters are The documentary history of the state of New-York . . . , ed. E. B. O’Callaghan (4v., Albany, N.Y., 1849–51) and NYCD (O’Callaghan and Fernow), especially vols. VI-VIII. Still unpublished are a number of his accounts in the Clements Library, Thomas Gage papers, and in PRO, AO 1 and T 64.

Two further works dealing with aspects of Johnson’s life are F. J. Klingberg, “Sir William Johnson and the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (1749–1774),” which appears in his Anglican humanitarianism in colonial New York (Philadelphia, 1940), 87–120, and Julian Gwyn, The enterprising admiral: the personal fortune of Admiral Sir Peter Warren (Montreal, 1974), which treats Johnson’s relations with his uncle. j.g.]

Cite This Article

Julian Gwyn, “JOHNSON, Sir WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 20, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/johnson_william_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/johnson_william_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | Julian Gwyn |

| Title of Article: | JOHNSON, Sir WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1979 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | December 20, 2024 |