Source: Link

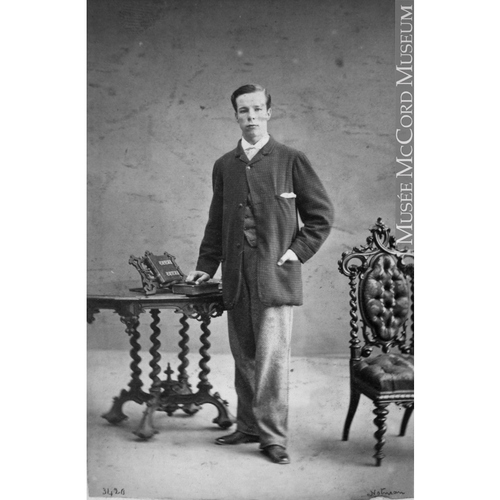

McCORD, DAVID ROSS, lawyer, alderman, and museum founder; b. 18 March 1844 in Montreal, fourth child of John Samuel McCord, a lawyer, and Anne Ross; m. 21 Aug. 1878 Letitia Caroline Chambers (d. 1928) in Toronto; they had no children; d. 12 April 1930 in Guelph, Ont., of myocardial failure.

Descended on his paternal and maternal sides from three generations of merchants, landowners, and jurists [see Thomas McCord*], David Ross McCord was raised in a family which valued both science and art. John Samuel McCord, who became a judge shortly after David’s birth, instilled a love of science in his children, provided them with a classical education, and insisted that they learn to speak French. Mrs McCord was fluently bilingual. Collecting was part of the family culture. David’s father was a connoisseur of art and his mother was an accomplished watercolour artist. Both she and David were taught drawing by James D. Duncan*.

McCord attended the High School of Montreal and then McGill College (ba 1863; ma, bcl 1867). He articled with the firm of Charles-André Leblanc* and Francis Cassidy* and was called to the bar in 1868. He practised alone, except for 1879–80, when he was in partnership with Joseph Doutre* and Moïse Branchaud, and he acted for the city of Montreal as well as for various institutions. He represented the descendants of Sir William* and Sir John* Johnson in their attempt to gain compensation from the American government for lands in New York State which had been confiscated after the American revolution. In 1895 he would be named a qc.

Continuing his father’s involvement in the Church of England, freemasonry, and the militia, McCord was a member of Christ Church Cathedral and St Paul’s Lodge and a lieutenant in the reserves. He was also active in urban reform, pursuing in particular issues of health and public sanitation as an alderman for Centre Ward from 1874 to 1882. In this work he met his future wife, Letitia Caroline Chambers, matron of the civic smallpox hospital. They were married despite the disapproval of his sisters, who had little regard for the occupation of nursing. His wife was a poet whose strongly imperialist verse would be published in Poems and songs on the South African War . . . (Montreal, 1901), edited by John Douglas Borthwick.

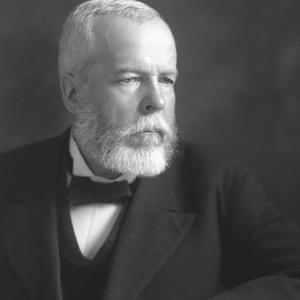

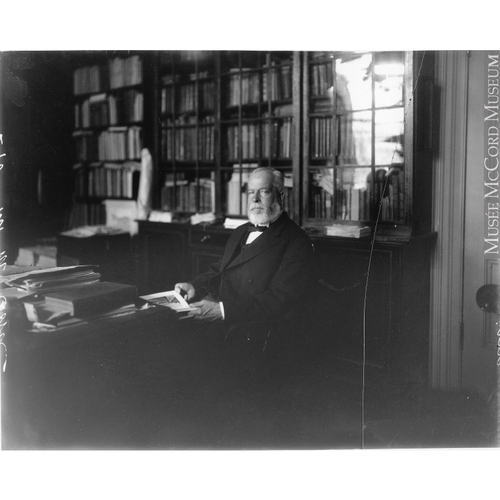

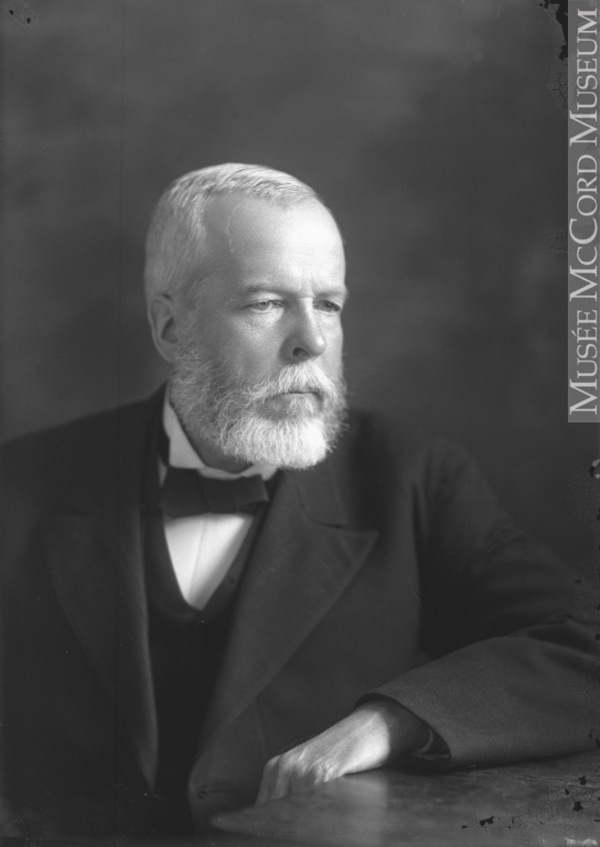

From about the 1880s, McCord’s chief interest was the collecting of material relating to the history of Canada, in which endeavour his wife acted as his assistant. The theoretical basis for his collection provides insight into the intellectual milieu in which his family ties and his research interests had placed him. In a climate of anxiety about the young country’s future, he, like other Canadian imperialists, turned to history to define, build, and defend the nation’s place within the empire. He read broadly in current works of history and literature in both French and English. He appreciated Quebec historians François-Xavier Garneau* and Henri-Raymond Casgrain*, who idealized the history of New France by emphasizing the conservative, agrarian, hierarchical, and religious nature of early French Canada. He chose themes recognizable to those who shared his imperialist views: Canada’s native cultures, the conquest of New France, the Seven Years’ War and Canada’s involvement in war, Catholic and Protestant church leaders who played a prominent role in building the country, romantic heroes of the fur trade, and Canadian scientists whose discoveries benefited the country and made it known abroad. His collection also reflected Montreal’s role in the development of Canada. Chosen mainly for their association with individuals, McCord’s acquisitions personified the events in Canadian history. He amassed his collection of roughly 18,000 artefacts from a variety of sources: his family, purchases, and donations obtained by sending flattering letters of appeal. In 1919, when he presented it to McGill University with an endowment, it was the largest collection of its kind in Canada. McCord’s friend and lawyer William Douw Lighthall* and McGill’s librarian, Charles Henry Gould*, had been instrumental in ensuring that the collection was acquired by McGill.

On 13 Oct. 1921 the McCord National Museum was officially opened. In its initial displays, McCord treated the leaders of Canada’s Christian traditions as spiritual pioneers, focusing on the theme of struggle and exhibiting the broadest range of objects, from early printed pamphlets, letters, portraits, and regalia to elements of church architecture which had been discarded during renovations. In collecting native material McCord had read the works of ethnologist Daniel Wilson*, geologist John William Dawson*, and philologist and ethnologist Horatio Emmons Hale*. Influenced by these three men who, according to anthropologist Bruce Graham Trigger, rejected “what modern anthropologists regard as some of the most abhorrent views of nineteenth-century anthropologists,” McCord hoped that his ethnological acquisitions “would stand unrivalled on the continent” as a testimony to “the skill and industry” of the native peoples. Prizing older material which reflected life before European contact, he also acquired a range of more recent artefacts for comparative purposes. Among the more spectacular items were his Micmac (Mi’kmaw) collection, an Iroquoian-type early-19th-century headdress believed to have been worn by the Shawnee leader Tecumseh*, an early Athapaskan jacket with quillwork decoration, and a significant collection of trade silver.

McCord referred to his paintings, prints, and drawings as visual records of the country’s progress. The initial displays drew on his collection of important family portraits by William Berczy*, Louis Dulongpré*, Frederick W. Lock, and James D. Duncan. He added his mother’s flower paintings and Duncan’s scenes of Montreal which his father had commissioned in 1831. He asked Henry Richard S. Bunnett to paint historic sites which he felt were destined to disappear. His most famous acquisitions are probably The negress (1786) by François Malepart* de Beaucourt, George Townshend*’s watercolour portrait of General James Wolfe* (the only known image drawn from life), a series of cartoons of Wolfe by Townshend, and 31 watercolours by William George Richardson Hind* executed during an expedition to British Columbia in 1862.

The collection’s material on western and northern expansion and exploration symbolized the romantic lure of the fur trade and the struggle to open up the country in the face of overwhelming obstacles. Maps, prints, silver, journals, and letters conjured up vast expanses of territory. Minutes of the Beaver Club, medals and portraits of its members, among them Isaac Todd*, Joseph Frobisher*, and James McGill*, and diaries of Arctic explorer Sir George Back* were among his prized possessions.

McCord believed that war refined the individual and the nation, providing national myths of heroism and sacrifice. Portraits, prints, paintings, uniforms, and weapons represented every battle, internal and external, in which Canadians had fought. He viewed the War of 1812 as Canada’s war of independence, in which native people and French and English Canadians fought alongside British regulars to defeat the invading Americans.

The considerable estate McCord had inherited had helped to finance his acquisitions, but his management of it during the period from 1870 to 1900 was, according to 20th-century historians, “marked above all by a remarkable inattention to legal obligations, often with costly consequences.” By the early 1900s, possibly earlier, McCord was experiencing financial difficulties. Later he suffered from arteriosclerosis, which led to mental deterioration. In early June 1922 Lighthall recommended interdiction (a legal restraint imposed on a person incapable of managing his or her own affairs) to McCord’s wife. It was granted on 29 June. In September McCord was admitted to the Protestant Hospital for the Insane in Verdun and the following year he became a patient at the Homewood Sanitarium in Guelph, where he remained, except for brief visits to Montreal, until his death.

David Ross McCord’s views on Canadian history were similar to those of many contemporaries who shared his enthusiasm for preserving the landmarks of their country’s past. He stands out among his peers, however, in three areas: the documentation of his artefacts (he accumulated 626 files of correspondence with donors or dealers, research notes, and bills), the obsessiveness of his collecting, and, finally, the comprehensiveness of his collection (he had also acquired thousands of books and pamphlets). He left to his university and future generations an invaluable legacy to serve in the interpretation and reinterpretation of Canadian history.

David Ross McCord’s papers are preserved in the McCord family fonds at the McCord Museum of Canadian Hist. (Montreal), 13 metres of records comprising his family’s papers and documentation concerning his activities as a collector. An inventory, McCord family papers, 1766–1945, comp. P. J. Miller (2v., Montreal, 1986), has been published by the museum. Another important source is P. [J.] Miller et al., The McCord family: a passionate vision (Montreal, 1992), a catalogue prepared for an exhibition at the McCord Museum. It examines the history of the family, studies each of McCord’s collections, and contains a select bibliography.

B. G. Trigger, Natives and newcomers: Canada’s “Heroic Age” reconsidered (Montreal, 1985). D. A. Wright, “Remembering war in imperial Canada: David Ross McCord and the McCord National Museum,” Fontanus (Montreal), 9 (1996): 97–104; “W. D. Lighthall and David Ross McCord: anti-modernism and English-Canadian imperialism, 1880s–1918,” Journal of Canadian Studies (Peterborough, Ont.), 32 (1997–98), no.2: 134–53.

Cite This Article

Pamela Miller, “McCORD, DAVID ROSS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mccord_david_ross_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mccord_david_ross_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Pamela Miller |

| Title of Article: | McCORD, DAVID ROSS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | April 25, 2025 |