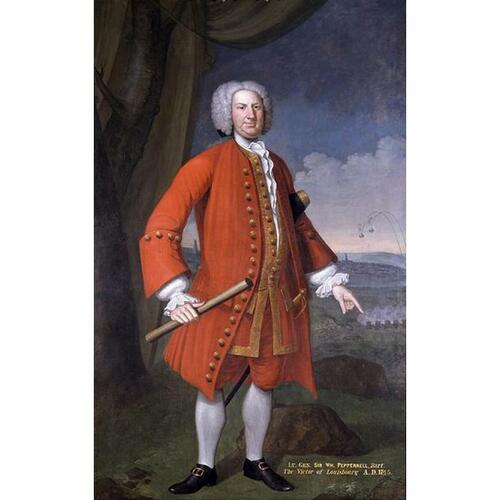

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

PEPPERRELL, Sir WILLIAM, merchant-shipowner, commander of the colonial forces that took Louisbourg, Île Royale (Cape Breton Island), in 1745; b. 27 June 1696 (o.s.) at Kittery Point, Massachusetts (now in Maine), son of William Pepperrell* and Margery Bray; m. 1723 to Mary Hirst, daughter of a wealthy Boston merchant and granddaughter of Judge Samuel Sewall, the diarist; they had four children, two of whom died in infancy; d. 6 July 1759 at Kittery Point.

Entering his father’s counting-house at an early age, the young William Pepperrell was forced by the death of his older brother in 1713 to assume much of the burden of the family business. By about 1730 the entire direction of the firm of “Messrs. William Pepperrell” was in his care. At that time the firm had 30 or 35 vessels under its management, and had a minor share in the ownership of a number of others. They ranged in size from small sloops to a brigantine of 110 tons and the ship Eagle, 180 tons. For the most part, the Pepperrell vessels shuttled back and forth from Kittery, northeast to Newfoundland, south to Virginia and Maryland and to the sugar islands – usually Antigua or Barbados – and across the Atlantic to Lisbon, Cadiz, the Canary Islands, Madeira, and England, in a pattern resembling the ribs of a Chinese fan. Unlike the vessels, the commodities in which the Pepperrells dealt followed labyrinthine lines that crossed and criss-crossed in a variety of geometric patterns.

Basic to the Pepperrells’ trade were two native products – lumber and fish – that were in brisk and widespread demand. Newfoundland, where they traded with William Keen and others, offered a ready market for pine boards and planks, oak staves and hoops, for rum, molasses, and sugar brought from the West Indies, and for tobacco, naval stores, livestock, and provisions that had come from North Carolina and the Chesapeake region. The return cargoes from Newfoundland consisted of English goods – textiles, cutlery, ironware, clothing and shoes, luxury goods such as silks, wines and brandy (which hinted at an illicit trade between Newfoundland and the Continent), and finally marine supplies for the New England shipping industry. Non-commodity returns – namely, money, bills of exchange, and passengers – were an important item in the Pepperrell ledger. Not all the passengers were emigrants deserting the Newfoundland fishing settlements; many of them were masters and crews of New England vessels that had been sold at the island. The same type of lumber cargoes that were shipped to Newfoundland comprised, with the addition of fish (cod, mackerel, and haddock), the outbound cargoes to the West Indies and to Spain and Portugal. For a number of years William Pepperrell owned an interest in fishing boats operating out of Canso, Nova Scotia, and Port-Toulouse (St Peters) on Île Royale. Later, the firm purchased its fish cargoes at Marblehead and Newburyport, Massachusetts, nearer home. It was not unusual for the Pepperrells to switch the direction of their trade back and forth according to the circumstances of the moment. If one general characteristic typified Pepperrell’s business activities, it was diversification and flexibility, made possible by the many vessels in which he held a controlling share.

Much of the surplus capital that came to the Pepperrells from their mercantile pursuits was invested in England, left on deposit with their London bankers. Surplus profits accumulated in New England were invested in loans and real estate. The Pepperrells became the neighbourhood bankers. William inherited from his father most of the harbourside land at Kittery Point and sizeable holdings in York and Saco. Later he acquired the larger part of present-day Saco and Scarborough, Maine, and eventually his landholdings, although by no means the largest in New England, lay scattered along the coast from Kittery to what is now Portland.

In Kittery, as elsewhere in coastal New England, shipping was a source of wealth, but land-ownership represented gentility and status, which in turn brought responsibility in the shape of public office and military command. In Kittery, the Pepperrells were one of nine families who constituted the “better sort” and among whom town and provincial offices were passed around and handed down from father to son and grandson. It was natural, therefore, that William Pepperrell in 1720, at the age of 24, should be chosen to represent Kittery in the provincial assembly. In 1724 and 1726 he was again chosen, to represent the town in Boston. Then, in 1727, at the age of 31, he was appointed by Governor William Dummer to a place on the Massachusetts Council board. It speaks well for Pepperrell’s prudence and tact that he retained his seat on the council throughout the turbulent politics of the next 32 years, under five different governors. For 18 of these years he presided over the council, where he soon established a reputation as an expert on military and Indian affairs. He also attended all the treaty conferences with the eastern Indians for almost 30 years. When Indians complained against the prices charged by the truckmasters at the forts or when settlers charged the Indians with depredations, Pepperrell was generally on the investigating committee.

In 1725 Pepperrell was appointed a judge on the York County Court and five years later he was elevated to chief justice. Like his colleagues on the bench, he was untrained in the law, but, from the point of view of the times, his qualifications were outstanding. His business experience gave him the competence to sit in judgement on many of the matters that came before the court; his fairness and personal integrity were unquestioned; and his rank and standing in the community brought respect and deference that gave added weight to his judicial decisions. Most of the cases were simple matters, but an ordinary action of trespass that came before Pepperrell in 1734 ended as one of the most celebrated legal battles of colonial times, Frost v. Leighton, a landmark in defiance against royal authority over the colonial timberlands.

Sometime in the 1720s William Pepperrell succeeded his father as colonel of the York County regiment of militia, in command of the entire region from the Piscataqua River to the Canadian border. Until the spring of 1744 the frontiers were nominally at peace and Pepperrell’s military duties were not too exacting, although there were alarms and incidents that kept the eastern outposts in an almost constant state of readiness. When war broke out in 1739 between England and Spain, Pepperrell summoned all the militia officers to a meeting at Falmouth (present-day Portland, Maine) to discuss problems of organization, discipline, and equipment. Vacancies in the ranks were filled, new companies were added to the regiment, and a new regiment was formed out of the militia from Falmouth eastward. Adopting a report of the council drafted by Pepperrell, the Massachusetts assembly voted funds to strengthen the harbour defences of Boston, Salem, Marblehead, and the other coastal towns. In the fall of 1743, when the situation became more threatening, Governor William Shirley notified Pepperrell that word of an imminent break with France had arrived from England. He directed Pepperrell “forthwith” to warn and secure the exposed frontier settlements against any sudden assault. Seven months later, on 12 May 1744, as a merchantman from Glasgow was entering Boston harbour with the long-expected news that France had declared war, a small French flotilla commanded by François Du Pont* Duvivier sailed from Louisbourg to attack the English settlement at Canso, which quickly fell to the superior French force. In August the French and their Indian allies attacked – this time unsuccessfully – the important English defence outpost at Annapolis Royal. Before the year was out, Governor Shirley had become convinced that the defence of Annapolis Royal, indeed the security of all New England, required the reduction of the French stronghold at Louisbourg.

On several past occasions when war had threatened, a number of colonials and a few Englishmen – among them William Pepperrell and Commodore Peter Warren – had set forth the idea of an assault on Louisbourg, but all the advocates had visualized an expedition from England with the colonies taking a minor role. Now Governor Shirley was audaciously proposing that it be a colonial undertaking, financed, directed, and carried out by the colonies alone, with perhaps some support from the British naval units stationed in American waters. Initially, the Massachusetts General Court had no more enthusiasm for a colonial expedition than there had been in England for an English expedition, but thanks to the influence and efforts of Pepperrell and other zealots such as William Vaughan and John Bradstreet*, the General Court eventually voted to enlist 3,000 volunteers and to provide whatever was necessary for the expedition. As chairman of the joint committee of the house and council that drew up the resolution for the expedition, Pepperrell helped to influence the General Court’s decision.

William Pepperrell was the logical choice to command the forces. The task of raising an army, keeping it intact, maintaining a respectable standard of discipline, and keeping relations with the Royal Navy on an even keel demanded those personal qualities for which he was noted. Pepperrell at first declined Shirley’s offer to command the expedition, but within a day or two he accepted the appointment. His long career as colonel of militia had made him thoroughly familiar with the problems of military administration and command, but Pepperrell (and more particularly his battalion majors) would have been in considerable difficulty if it had become necessary to put the troops through the intricate manoeuvres by which an 18th-century army was deployed into line of battle. But they were not counting on meeting the French in the open field; the problem was to assault a fortress. The plan of assault which Pepperrell took with him to Louisbourg had been drafted by Shirley, possibly with the aid of Philip Durell and John Henry Bastide. It called for a surprise attack on the fortress, but authorized Pepperrell to act at his discretion should unforeseen circumstances arise.

On 24 March 1744/45 the Massachusetts forces sailed from Boston for Canso, where they arrived on 4 April. They were joined there by smaller contingents from New Hampshire and Connecticut and by a naval squadron from the West Indies under the command of Commodore Peter Warren. Estimates of the total number of New Englanders who eventually faced the French at Louisbourg range up to some 4,300 men; probably the effective strength at any one time amounted to half that figure. After stopping at Canso for some three weeks, the New England forces arrived off Louisbourg early on 30 April. With the help of good luck, good weather, and good boatmanship, nearly 2,000 men gained the beach at the head of Gabarus Bay within the space of eight or ten hours. No opposition was met until the first troops were on shore, when a small French detachment under the command of Pierre Morpain made an ineffective sortie. By this time, Pepperrell had shelved the original plan and adopted as an alternative a formal siege, a highly standardized process of advancing guns and men up to the walls in a series of parallel trenches connected by zigzag approaches. The New Englanders, however, astounded the French by dragging their heavy cannon through a marsh considered impassable, and then moving the guns into position under cover of night and fog instead of first digging trenches to protect the advance. The second morning after the landing, a small party under William Vaughan discovered that one of the key points of the defences – the Grand (Royal) battery – had been abandoned. Vaughan occupied it, and soon the guns of the battery were brought into action against the town.

Although the New England army had its share of chronic grumblers and malcontents, during most of the siege the men faced the dangers and hardships bravely and light-heartedly. Plundering in the countryside around Louisbourg was a troublesome problem for the New England commanders, however, particularly during the early days. Several unsuccessful and costly attacks against the Island battery, which commanded the harbour entrance [see Waldo], brought matters to a standstill, and as the siege went into its fourth week the morale of the New Englanders sank very low. But at a certain point, according to the formula of 18th-century siege warfare, the defenders of a fortress would know whether they must capitulate. When the New England forces established a battery on Lighthouse Point, overlooking the Island battery, the French position became untenable. The harbour lay open to Warren’s fleet and on 15 June the acting governor Louis Du Pont* Duchambon decided to ask for terms. Negotiations ended on the afternoon of 17 June when, after a siege of seven weeks, Louisbourg surrendered. The terms of the capitulation [see Warren] included permission for the officers and townspeople to remain in their homes and to enjoy the free exercise of their religion until they could sail for France, and a guarantee that no personal property would be disturbed.

The reduction of the French stronghold set all the church bells in Boston ringing, produced applause in London, and brought fame and honour to William Pepperrell. As a reward for merit, King George II commissioned Pepperrell colonel in command of a regiment in the regular army – the 66th Regiment of Foot – and conferred on him a baronetcy. But to the rank and file of the army at Louisbourg, the surrender presented no great cause for rejoicing. Disgruntled at being denied plunder – especially since the fleet had taken several rich prizes – and discouraged at the prospect of having to remain on garrison duty, some of the troops threatened to lay down their arms. Moreover, relations between the land and sea forces deteriorated. Minor differences between Pepperrell and Warren during the siege and at the time of surrender were magnified in camp rumours into an attempt by Warren to claim chief credit for the victory, and were further exaggerated in Boston. The troops were not appeased until a large pay increase was promised them and reinforcements began to arrive. Sir William Pepperrell, as he now was, remained in Louisbourg until late May 1746. He served jointly with Warren in administering the affairs of the town and garrison, and spent much of his time on matters relating to his regiment. The major problem during the winter and spring was disease among the troops. Estimates of the number of deaths range from 1,200 to 2,000.

On his return to New England, Sir William resumed his seat on the council board and prepared to live the life of a country squire at Kittery. When the provincial government appealed to the Privy Council for reimbursement of the costs of the expedition, Pepperrell and Warren were called upon to examine and verify all the accounts. In the fall of 1749 Sir William went to England, where for a year he was something of a lion. His old comrade-in-arms, Peter Warren, welcomed him cordially; the city of London presented him with a handsome silver service, and he made his appearance at court. By this time, however, the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748) had undone his great achievement by returning Louisbourg to the French. Colonials, including Pepperrell, were bitter.

His regiment disbanded, Pepperrell returned to New England in October 1750, and settled down in his mansion overlooking the harbour at Kittery. He had no intention of resuming his mercantile career, but the death in 1751 of his son Andrew, who had been managing the business for some years, forced Sir William to take the helm again. In 1754, when a frontier incident on the western slopes of the Allegheny Mountains [see Joseph Coulon de Villiers] ushered in the Seven Years’ War in America, Pepperrell’s regiment was restored to the army list as the 51st; but for Sir William the war was an anticlimax. Although plagued by ill health, he had hoped to lead his regiment against the French at Fort Niagara (near Youngstown, N.Y.), but his promotion to major-general in June 1755 meant, according to General Edward Braddock, the British commander in North America, that he could not “with any propriety” take the field as colonel of his regiment.

Pepperrell returned to Boston from his regimental headquarters in New York and resumed his seat on the Massachusetts Council. After the death of Lieutenant Governor Spencer Phips in the spring of 1757, Sir William served as acting governor of Massachusetts for four months until the arrival of the new governor, Thomas Pownall. The aging conqueror of Louisbourg lived to see Jeffery Amherst* and James Wolfe, with 9,000 British regulars and 40 ships of war, duplicate his feat in 1758. The following year Pepperrell became the only native American to receive a commission as lieutenant-general in the British army. The honour came almost too late, for by May he was dangerously ill. He lingered on for two months more, and then on Friday, 6 July 1759, Sir William Pepperrell died, greatly lamented.

Although Amherst and Wolfe won a measure of acclaim from colonials for their exploits at Louisbourg and Quebec, Sir William Pepperrell was, to the post-1745 generation of Americans, the foremost military figure of the colonies. For 30 years his fame endured, until a famous musket shot on Lexington Green created a whole new set of heroes.

The principal manuscript collections of Pepperrell papers are those of the Harvard College Library, the New England Historic Genealogical Society, the Massachusetts Historical Society, and the privately held collection of Joseph W. P. Frost, Kittery Point, Maine. Other valuable documentary sources are the town records of Kittery (Maine), Books I–II (1648–1799), and the Warren papers and Louisbourg papers of the Clements Library.

See also: Correspondence of William Shirley (Lincoln). Louisbourg journals (De Forest). Mass. Hist. Soc. Coll., 1st ser., I (1792). “The Pepperrell papers,” Mass. Hist. Soc. Coll., 6th ser., X (1899). Province and court records of Maine, IV, V. R. G. Albion, Forests and sea power; the timber problem of the Royal Navy, 1652–1862 (Harvard economic studies, XXIX, Cambridge, Mass., 1926). Byron Fairchild, Messrs. William Pepperrell: merchants at Piscataqua (Ithaca, N.Y., 1954). J. W. P. Frost, Sir William Pepperrell, bart., 1696–1759, his Britannic majesty’s obedient servant of Piscataqua (Newcomen Soc. in North America pub., New York, 1951). J. J. Malone, Pine trees and politics; the naval stores and forest policy in colonial New England, 1691–1775 (Seattle, [1964]). McLennan, Louisbourg. Parkman, Half-century of conflict. Usher Parsons, The life of Sir William Pepperrell, bart. . . . (1st ed., Boston, 1855; 2nd ed., Boston, London, 1856). Rawlyk, Yankees at Louisbourg. W. G. Saltonstall, Ports of Piscataqua; soundings in the maritime history of the Portsmouth, N.H., customs district . . . (Cambridge, Mass., 1941). J. A. Schutz, William Shirley: king’s governor of Massachusetts (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1961). E. S. Stackpole, Old Kittery and her families (Lewiston, Maine, 1903).

Cite This Article

Byron Fairchild, “PEPPERRELL, Sir WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 3, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 5, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pepperrell_william_3E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pepperrell_william_3E.html |

| Author of Article: | Byron Fairchild |

| Title of Article: | PEPPERRELL, Sir WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 3 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1974 |

| Access Date: | January 5, 2025 |