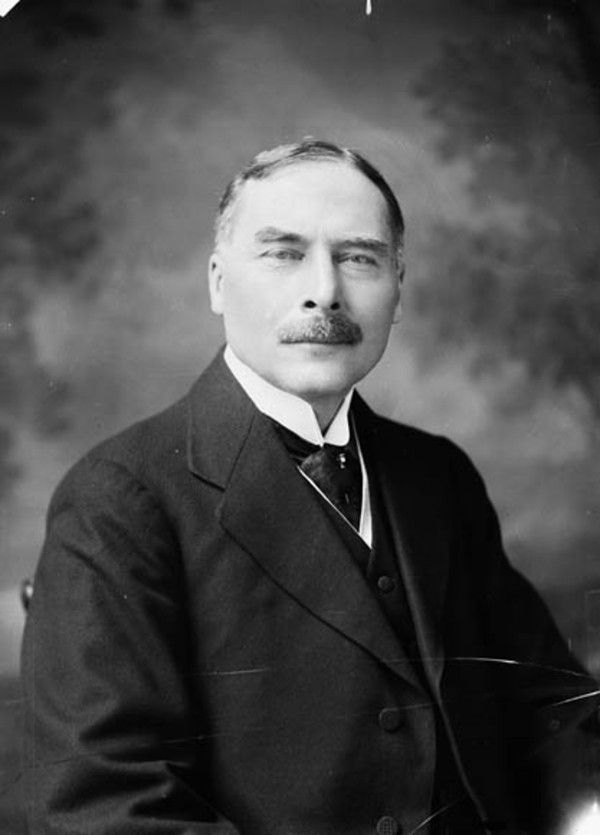

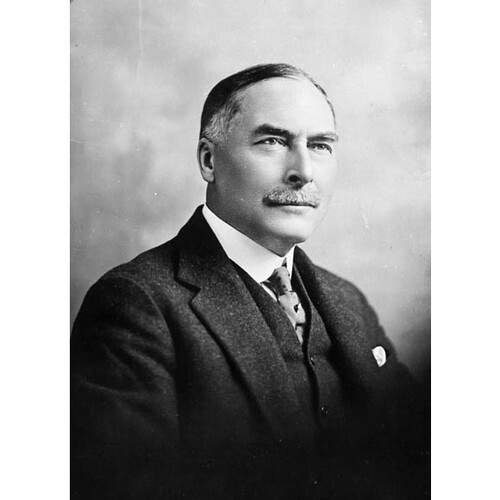

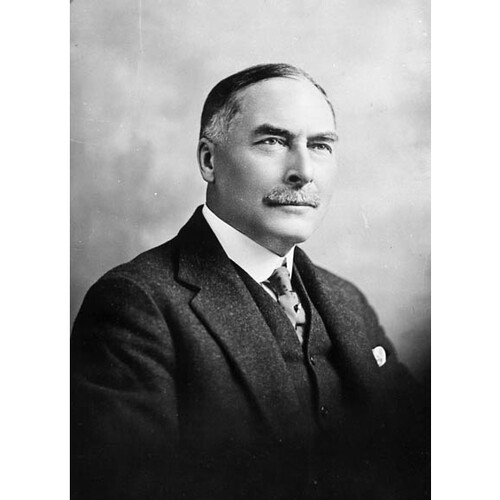

LOUGHEED, Sir JAMES ALEXANDER, carpenter, lawyer, businessman, and politician; b. 1 Sept. 1854 in Brampton, Upper Canada, son of John Lougheed and Mary Ann Alexander; m. 16 Sept. 1884 Isabella (Belle) Clarke Hardisty* in Fort Calgary (Calgary), and they had four sons and two daughters; d. 2 Nov. 1925 in Ottawa.

James Lougheed’s family was of Protestant Irish descent, his father being born in Upper Canada and his mother in Ireland. When James was two or three they moved from Peel County to Toronto. The young boy grew up in Cabbagetown, the poorer eastern section of the city. The family were of modest means; in James’s teenaged years they rented a small frame house at the junction of Queen and River streets, near the Don River. James attended the Park Street School. According to his obituary in the Calgary Herald, Lougheed often attributed his success to the early influence of his mother, a devout and active worker at Berkeley Street Methodist Church. She sent him to two Sunday schools: Little Trinity Anglican in the morning and Berkeley Street in the afternoon. It was a strict upbringing. Berkeley Street Methodists, his lifelong friend Emerson Coatsworth would later comment, “did not play cards or dance. We did not attend the theatre or the races.” Lougheed and Coatsworth shared Orange connections as well. In 1936 James’s first cousins Jane and Elizabeth Lougheed would remember that while a stripling he had been a chaplain in the Orange Young Britons – he “wore a white gown and carried a Bible at Parades.”

James’s father intended that his sons follow him into carpentry and the building trade, which James did after leaving school. In 1869 the firm for which James worked also employed William Pearce, a surveyor and later a prominent Calgarian. After Lougheed’s death in 1925, Pearce would recall his acquaintance with him in 1869–70: “He was then a very young man, in fact he was regarded as a boy, but he was always very industrious and aggressive.”

Although his father may have been pleased with his progress, his mother was not. She wanted him to consider options other than the building trades. She encouraged him, after he had left school, to continue attending the two churches on Sunday. At Little Trinity he came to know Samuel Hume Blake*, a distinguished layman and eminent lawyer, after volunteering to become the church’s assistant librarian. Blake took a liking to the clever young man, and once said to him: “Boy you have too good a head to be a carpenter, why don’t you take up law?” James relished the idea and went back to school; he chose Weston High School, west of Toronto. Upon his return to Cabbagetown, he and Coatsworth prepared together for their matriculation exams for entrance to Osgoode Hall, which they passed in 1875. In 1876 or 1877 Lougheed was articled to the local law firm of Beaty, Hamilton, and Cassels, and in May 1881 he would be sworn in as a solicitor.

Following his return to Toronto, James, his younger brother Samuel, Coatsworth, and six others formed the Awascal Literary Society at Berkeley Methodist Church. All that survives of this club is a financial account by treasurer Coatsworth of an oyster supper held on 30 Dec. 1876. Before his death in 1925, Lougheed told a reporter that it was at the Awascal society that he had received his “early training as a speaker.” He may well have put this training to use in 1878, when, as a member of the Young Men’s Conservative Club, he fought hard in the successful campaign to return Sir John A. Macdonald* to power. It was not surprising, given his Orange background, that he identified with the Conservatives. According to his cousins, his political interests had always run deep and he had often spent his spare time attending the provincial parliament, “where he liked to listen to the speeches.”

In January 1882 Lougheed, now a practising lawyer, decided to move with his brother Sam to Winnipeg. A year later, following the Canadian Pacific Railway’s construction teams, James moved farther west to Medicine Hat (Alta). Then, just before the rails reached the hamlet of Fort Calgary in August 1883, he and Sam moved there. Lougheed’s marriage to Belle Hardisty, the daughter of the late William Lucas Hardisty*, a Hudson’s Bay Company chief factor in the Mackenzie River district, and his wife, Mary, an English-speaking mixed-blood woman, solidified James’s links with the west. Belle had received a good education, at Mathilda Davis*’s school in St Andrews (Man.) and then at the Wesleyan Female College in Hamilton, Ont. James met her in Fort Calgary while she was visiting her uncle Richard Charles Hardisty*, chief factor of the HBC’s Upper Saskatchewan district. Through this marriage Lougheed acquired a close connection to both Richard Hardisty, the richest man in the North-West Territories, and to Donald Alexander Smith*, his wife’s uncle by marriage and soon to be one of the wealthiest men in Canada.

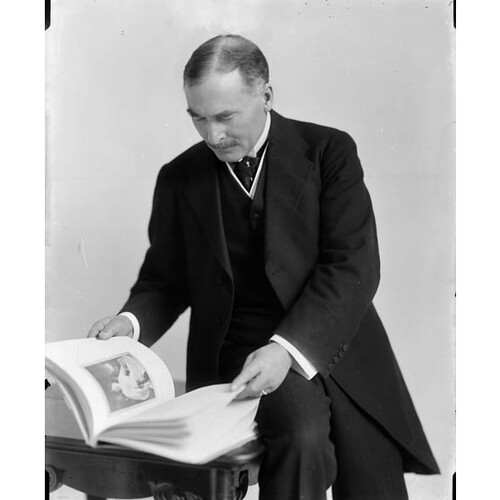

James’s legal practice thrived. The CPR soon became one of his most important clients. In 1887 he formed a partnership with Peter McCarthy and two years later he became a dominion qc. In 1911 he would add to his legal business a brokerage firm, Lougheed and Taylor Limited. As well, beginning in the 1880s, he made good investments in Calgary real estate, building many rental properties in the downtown area. His show-piece, the Lougheed Building, an office block that included a 1,500-seat theatre, the Sherman Grand, was completed in 1912. In 1891–92 the Lougheeds had erected a magnificent sandstone mansion, Beaulieu, in southwest Calgary. The Duke of Connaught [Arthur*], the governor general of Canada, would stay here with his family in 1912 and the Lougheeds held a huge garden party for the Prince of Wales in 1919. And it was at Beaulieu that Belle Lougheed, Calgary’s principal hostess, raised their children. She also took an active part in a good number of community organizations. For example, she was the first treasurer of the Women’s Hospital Aid Society (1890), vice-president for the Alberta district of the National Council of Women of Canada (1896), first vice-regent of the Colonel Macleod Chapter of the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire (1909), first president of the Women’s Pioneer Association of Southern Alberta (1922), and first president of the Calgary branch of the Victorian Order of Nurses.

In many ways Lougheed seemed far removed from his humble Toronto origins. He took no part in the Orange lodge in Alberta and never talked about his Cabbagetown roots; moreover, contrary to his Berkeley Street Methodist teachings, he and his wife hosted dances in their mansion and developed a strong interest in the theatre. As Maynard J. Joiner, the Grand’s manager in the mid 1920s, said of James Lougheed, “Whenever in the city one of his greatest delights was to be present at one of our performances.”

Shortly after his arrival in Alberta the former Torontonian had become a strong champion for western interests. Charles Edward Dudley Wood, the editor of the Fort Macleod Gazette, wrote of him in late 1890, “He is an Alberta man first, last and everytime.” After Richard Hardisty, a federal senator, died in 1889, Lougheed was selected as his successor. Called to the Senate on 10 Dec. 1889, he became, at 35, its youngest member. In addition to his relationship to Hardisty and Smith, he was a personal friend of interior minister Edgar Dewdney*. He had met Sir John A. Macdonald in Calgary in 1886, had been consistently loyal to the prime minister amidst the volatile western politics of the 1880s, and was a prominent investor in the Conservative Calgary Herald. The Reverend Leonard Gaetz, a leading Tory in the Red Deer district, had spoken for many when he wrote in October 1889, “Mr. Lougheed is incomparably the best name we can offer. He is a gentleman of culture, ability & position with thorough knowledge of and faith in Alberta, a Conservative of the Conservatives, a good address, and will make I believe a first class representative.” Lougheed subsequently moved back and forth between Calgary and Ottawa. To give him more time to look after his extensive political and business interests, he would persuade Richard Bedford Bennett*, a young New Brunswick lawyer, to join his law firm. Bennett arrived in January 1897 and they would work together for over two decades, until Lougheed’s attempt to dissolve their partnership without Bennett’s agreement caused a bitter quarrel and separation in 1922.

During the 1890s Lougheed emerged in the Senate as a true representative of the west and an advocate of provincial status. Frequently he educated his colleagues concerning the nature of the region and its institutions, about the impact there of past legislation, and on the need to ensure that the west was fully comprehended in various statutes. He spoke often enough to be noticed, yet avoided challenging the Senate’s seasoned gladiators. He also used his considerable legal skills to improve legislation, especially in the committee stage of detailed consideration. Gradually he broadened his perspective, learning to speak from a national as well as a western perspective. His sheer ability, diplomacy, and geniality won him respect. In 1906 he was elected by his colleagues to succeed Sir Mackenzie Bowell* as the Conservative leader in the Senate, a position he would occupy until his death.

With respect to the Autonomy Bills, introduced in the House of Commons in February 1905 to create the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan, Lougheed had been predictably partisan, particularly concerning the education clauses. Better to forgo provincial status, he remarked darkly in an interview in Winnipeg on 27 February, than to have the hands of the new provinces “tied for all time to come on this question of Education.” It was not a “sectional” or regional issue; rather, it was a constitutional one, “a deliberate assault on Provincial rights, the fundamental basis of our political fabric.” He also denounced the federal government’s gerrymander of seats in the new provinces, intended to produce strong Liberal majorities in the new provincial legislatures. His objections naturally were ignored by the Liberal government.

From 1911, when the Conservatives came to power, to 1921 Lougheed was the government leader in the Upper Chamber and a member of cabinet. For at least the first five of these years his diplomatic skills were tested to the full as he had to try to steer the legislation of the government of Sir Robert Laird Borden* through the Senate while the Conservatives had a minority of seats there. As long as Sir Wilfrid Laurier*’s Liberals held the majority, they could and did defeat numerous measures. From about 1917 Lougheed was able to command a majority most of the time, though it was not always reliable given the independent-mindedness of some senators.

Within cabinet he served as a minister without portfolio (October 1911–February 1918), minister of soldiers’ civil re-establishment (February 1918–July 1920), and then, under Arthur Meighen*, minister of the interior (July 1920–December 1921), a portfolio that included Indian affairs and mines. During most of this ten-year period he was the sole member of the Upper Chamber who could speak for the cabinet, and as such he had to master the full range of government legislation – a task required of no minister in the commons.

Lougheed was thoroughly conservative in his views, beginning with the role of the Senate. “This is a revising body,” he remarked in 1904; its duty was to keep a rein on popular enthusiasms and “to check hasty legislation.” In debates he favoured business and free enterprise. “Parliament exists, not for the purpose of wrecking the interests of the producer,” he said in 1918, “but rather to protect them.” He deplored excessive taxation and the “paternalism” of subsidies and protective tariffs. In 1897 he had objected to a bill to create the Victoria Day holiday on the ground of loss of business. He contended that outsiders provoked much of the labour trouble in Canada, and in 1903 tried to have the Criminal Code amended “to prevent alien agitators from coming into Canada and organizing strikes.” Following the Winnipeg General Strike in 1919 [see Mike Sokolowiski*], he strongly supported the government’s anti-sedition legislation.

Lougheed also shared common western conservative views about Canada’s native peoples and immigrants. Canada, in his opinion, had by far the best record of any country of dealing with its indigenous peoples. He firmly believed that they required strong, paternal supervision and must not be allowed to impede progress. While in opposition he had wanted the government to take power to sell Indian lands, especially when they were located close to settlements, which he thought demoralized the natives. After his own party came to power, he strongly supported its 1914 measure to initiate sales. In 1920 he fully supported a Conservative bill to force compulsory enfranchisement or the elimination of Indian status under the Indian Act. Two years later he strenuously opposed as “retrograde and reactionary” the decision of the new Liberal government of William Lyon Mackenzie King* to repeal compulsory enfranchisement. Lougheed had been uncharacteristically extreme – though fully representative of his fellow Alberta Conservatives – in denouncing the immigration policy of the Laurier government. “We will have the very excrescence of European immigration placed on our shores,” he huffed. Miraculously, however, under the Borden government, immigrants became subjects of Lougheed’s praise.

In 1910 Lougheed, an admirer of the British empire, had opposed Laurier’s Naval Service Bill. It provided, he thought, inadequate help to Britain in the emergency of the European naval race and he feared that establishing a separate Canadian navy would lead to the severance of Canada from the empire. His proposed amendment, to submit the question to the country, was defeated by the Liberal majority. In 1913 the Borden government used closure to force its Naval Aid Bill, intended to give Britain $35 million for construction, through the commons. Lougheed negotiated an arrangement with Senate Liberal leader Sir George William Ross* to amend the legislation to provide for an appropriation for a Canadian navy, in return for passage of the bill. Enraged by the government’s use of closure, however, Laurier and most of the Liberal senators were determined to defeat the measure. Nonetheless, Lougheed introduced it. He outlined the government’s case in impressive detail in the longest speech of his career, nearly three hours, but the Senate killed the bill by passing an amendment similar to Lougheed’s in 1910 – that the naval policy be put to the people.

Upon the outbreak of war in 1914, Lougheed exhibited a restrained commitment to seeing the “dominions . . . march in step with the armies of the empire.” But with his son Clarence Hardisty serving overseas, his response to the war, like that of many other Canadians, became personal and emotional. By 1916 he was convinced that Germany meant to convert Canada “into a trans-Atlantic Germany.” Thus the war was a struggle for national survival and the Military Service Act of 1917 was an “extraordinary” law necessary for “the preservation of the state.” He rejected the idea of a referendum on conscription: why should the government ask the opinion of pacifists, slackers, and socialists, men who “proclaim their disloyalty from the house tops”? When Senator Philippe-Auguste Choquette* requested that implementation of conscription be suspended until after the 1917 election, Lougheed responded vehemently, “I propose that any member of this House who preaches sedition, as this honourable gentleman is doing, will not be heard by this House.” He observed, during his introduction of the War-time Elections Bill in 1917, that the emergency justified setting aside some venerated traditions. The essential principle of the bill, he said, was “if a man objects to fight he should not be permitted to vote.” Clearly winning a war to preserve democracy justified, for Lougheed, limiting the democratic rights of many Canadians.

As the war proceeded, Lougheed assumed increasing responsibilities for the government, in recognition of which he would be made kcmg on 3 June 1916. In June–September 1915 he was acting minister of militia and defence in the absence of Samuel Hughes. He found the department in chaotic disarray, and spent much time trying to get shell production properly coordinated between Canada and Great Britain. He also raised donations from the public for machine guns. In response to complaints concerning the treatment of returned wounded soldiers, the government in June 1915 established the Military Hospitals Commission; on 3 July Lougheed became its chair. It supervised hospitals and other long-term care facilities, retrained and helped find employment for those able to work, coordinated the effort with the provinces, and solicited public support. In October Borden also asked Lougheed to chair the Commission on Natural Resources, which was expected to solve the problem of unemployment by suggesting methods for improving agriculture and the marketing of goods internally and abroad, locating land for agricultural development, and considering how returned soldiers might be employed and how more capital might be raised for both agriculture and manufacturing. A plan for soldier settlement suggested by the commission in 1916 had little appeal, so the government devised quite a different scheme the following year. In 1918 the work of the Military Hospitals Commission was divided into two departments: the militia department took over most of the military hospitals, while the new Department of Soldiers’ Civil Re-establishment assumed the remaining duties of the commission and planned for demobilization and the reabsorption of soldiers into society and the economy. From June 1920 to September 1921, Lougheed, in addition to performing his duties as interior minister, would serve as acting minister of soldiers’ civil re-establishment. Historians Desmond Morton and Glenn Wright, though they recognize Lougheed’s role in establishing the Military Hospitals Commission and the new department, contend that he was chronically indifferent to the affairs of the commission and to veterans’ problems generally.

In 1919 Lougheed played a prominent role in the Senate’s consideration of two important post-war measures, one external, one domestic. In presenting the Treaty of Versailles for ratification, he noted that Canada had made a significant advance in international status as a signatory and as a member of the League of Nations. He argued in favour of article 10 of the league’s covenant, which bound members to support the territorial integrity of other member nations when under attack. Apparently he was unaware that Borden and his Canadian colleagues at Paris, fearful of involvement in future European wars, had tried to eliminate or modify the article throughout the negotiations leading to the treaty and would continue to do so thereafter. On the home front, Lougheed shepherded through the Senate the contentious Grand Trunk Railway acquisition bill, designed to round out the government’s accumulation of bankrupt railways that would lead to the formation of the Canadian National Railways. Even senators opposed to the bill recognized his introductory speech as “a brilliant oration.” The real work, however, was accomplished in committee, where Lougheed demonstrated mature diplomacy and leadership. Still, since several Conservative senators were passionately opposed to government ownership, the bill carried only by the narrow margin of 39 to 35.

In the fall of 1920, while interior minister in the short-lived Meighen administration, Lougheed was responsible for amending existing policy when he opened the crown forest reserves on the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains to petroleum exploration, a change long desired by Calgary oilmen but previously resisted by the interior department. The new policy required that a leased area be divided into two equal parts, one of which would generate revenue for the crown. This policy, further modified after the discovery of oil at Leduc in 1947, ultimately became the means by which vast sums were transferred to Alberta’s treasury. Lougheed was instrumental as well, in 1921, in passing the legislation that killed the Commission of Conservation, established in 1909 [see James White]. Resentful of the powers it had exercised at arm’s length from government control, he claimed that it had duplicated the work of at least six government departments and that its abolition would save some $250,000 annually. Shortly thereafter he supported a bill to establish “a National Research Institute,” which would allow the government to centralize all its scientific and research work in Ottawa and to place it under ministerial control [see Robert Fulford Ruttan]. This bill, however, failed to pass.

After the defeat of the Meighen government by the Liberals under King later in 1921, Lougheed continued to lead the Conservatives in the Senate. The new government was just shy of a majority in the commons, and the Conservative majority in the Senate had no intention of being cooperative. Among the measures rejected was the Canadian National Railways construction bill in 1923, during a session marked by unusually aggressive partisanship as the parties tried to position themselves for the next election.

Lougheed was seriously ill early in 1925, but he seemed to be recovered when he returned to his duties in May. In July, anticipating an election call, Meighen summoned him back to Ottawa again to assist with electoral organization, a task, along with patronage, at which the Calgary senator had always excelled. The work continued into the fall when, during the coldest October then on record for the nation’s capital, Lougheed contracted bronchitis, which turned to pneumonia. He succumbed on 2 November in the Ottawa Civic Hospital, and was buried in Calgary on the 8th. In the year of his death a village in central Alberta was renamed Lougheed in his honour. A small peak west of Banff was named after him as well, in 1926, but two years later the name was transferred to a larger, more accessible peak on the edge of the Rocky Mountains near Canmore. Earlier, in 1916, Vilhjalmur Stefansson* had explored one of the Queen Elizabeth Islands, in what is now Nunavut, and designated it Lougheed Island.

Sir James Lougheed was a true Victorian believer in hard work and the idea of progress. Thanks to the timing of his arrival in Calgary, his training as a carpenter and a lawyer, and his marriage to a woman whose family had power and wealth in the northwest, this ambitious and capable Torontonian became the dominant business and political figure in Calgary at the turn of the century. He also served most competently on the national level as a cabinet minister and a party leader in the Senate, which, in his day, largely represented an aristocracy of business and the law. In many respects Lougheed was the exemplar of the ideals of the Senate; perhaps only Raoul Dandurand* commanded equal regard. Not only had Lougheed risen above his background, he had also acquired and honed the industriousness, the courtly manners, and the political skills that enabled him to reach a position of leadership and respect among his peers and the wider public.

[One of Lougheed’s boyhood books, Thomas Pelham Dale’s A life’s motto illustrated by biographical examples (London, [1869]), is held by the Lougheed House Conservation Society, which looks after the Lougheed mansion and gardens in Calgary. The motto, from Ecclesiastes, is “Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with thy might; for there is no work, nor device, nor knowledge, nor wisdom, in the grave, whither thou goest.” The book contains the handwritten inscription “Presented to James A. Lougheed for punctuality and attention at Trinity Sunday School from his teacher, October 15, 1869.” Lougheed must have valued this book highly since he kept it all his life and passed it on to his eldest son, Clarence, a lawyer with Lougheed and Taylor.

The authors wish to thank Professor David H. Breen of the University of British Columbia for his comments on the issue of crown reserves. d.j.h. and d.b.s.]

AO, F 332, 3 April 1936. GA, M 927; M 928; M 4843, files 13–14. Glenbow Library (Calgary), James Lougheed file. NA, MG 26, A; G; H; I; K. Private arch., Jamie Coatsworth (Toronto), “Awascal Literary Soc., Toronto, Dec. 30/[18]76: ‘Report of oyster supper.’”. Calgary Albertan, 3, 10 Nov. 1925. Calgary Herald, 21 March 1922; 1 Sept., 2–3 Nov. 1925; 8 July 1950; 15 June 1997; 29 May 1999. Globe, 23 Feb. 1918. Mail and Empire (Toronto), 14 March 1936. Manitoba Free Press (Winnipeg), 11 Aug. 1924. Morning Albertan (Calgary), 15 Sept. 1919. Ottawa Citizen, 2–3 Nov. 1925. Norman Anick, Sir James Alexander Lougheed ([Ottawa], 1991). R. L. Borden, Robert Laird Borden: his memoirs, ed. Henry Borden (2v., Toronto, 1938). D. [H.] Breen, Alberta’s petroleum industry and the Conservation Board (Edmonton, 1993); The Canadian prairie west and the ranching frontier, 1874–1924 (Toronto, 1983). Can., Parl., Sessional papers; Senate, Debates, 1890–1926. Canadian annual rev., 1901–25. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). Raoul Dandurand, Les mémoires du sénateur Raoul Dandurand (1861–1942), Marcel Hamelin, édit. (Québec, 1967). Janet Foster, Working for wildlife: the beginning of preservation in Canada (Toronto, 1978). H. F. Gadsby, “The Borden cabinet – X: the government leader in the Senate,” Canadian Liberal Monthly (Ottawa), 1 (1913–14): 123. M. F. Girard, L’écologisme retrouvé: essor et déclin de la Commission de la conservation du Canada (Ottawa, 1994). “James Lougheed of Britannia,” comp. Jopie Loughead et al. (n.p., 1998). A. O. Jennings, “Lougheed & Taylor, Limited, financial brokers,” in Calgary, Alberta, merchants and manufacturers record: the manufacturing, jobbing and commercial center of the Canadian west ([Calgary, 1911]), 98–99. Madeleine Johnson, “Lady Isabella Lougheed” (research report, [Calgary?], 1996; copy at Lougheed House Conservation Soc. arch.). H. C. Klassen, “Lawyers, finance and economic development in southwestern Alberta, 1884 to 1920,” in Essays in the history of Canadian law, ed. D. H. Flaherty et al. (8v. to date, [Toronto], 1981– ), vol.4 (Beyond the law: lawyers and business in Canada, 1830 to 1930, ed. Carol Wilton, 1990), 298–319. M. C. McKenna, “Sir James Alexander Lougheed: Calgary’s first senator and city builder,” in Citymakers: Calgarians after the frontier, ed. Max Foran and S. S. Jameson (Calgary, 1987), 95–116. Desmond Morton, “‘Noblest and best’: retraining Canada’s war disabled, 1915–23,” Journal of Canadian Studies (Peterborough, Ont.), 16 (1981), nos.3–4: 75–85. Desmond Morton and Glenn Wright, Winning the second battle: Canadian veterans and the return to civilian life, 1915–1930 (Toronto, 1987). Prominent men of Canada: a collection of persons distinguished in professional and political life, and in the commerce and industry of Canada, ed. G. M. Adam (Toronto, 1892), 118–19. W. K. Regular, “Regionalism, nationalism and the Canadian character: the Senate career of James A. Lougheed, 1890–1905” (ba dissertation, Memorial Univ. of Nfld, St John’s, 1978). John Richards and Larry Pratt, “Oil and social class: the making of the new west,” in Riel to reform: a history of protest in western Canada, ed. George Melnyk (Saskatoon, 1992), 224–44 . G. H. W. Richardson, “The Conservative party in the provisional district of Alberta, 1887–1905” (ma thesis, Univ. of Alta, Edmonton, 1977).

Cite This Article

David J. Hall and Donald B. Smith, “LOUGHEED, Sir JAMES ALEXANDER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 2, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lougheed_james_alexander_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lougheed_james_alexander_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | David J. Hall and Donald B. Smith |

| Title of Article: | LOUGHEED, Sir JAMES ALEXANDER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | April 2, 2025 |