As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

Source: Link

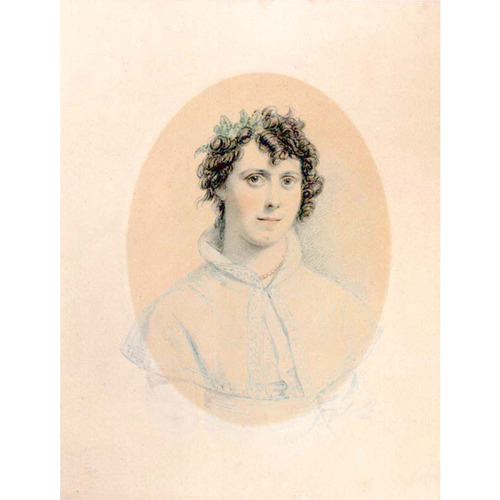

STRICKLAND, SUSANNA (Moodie), settler and author; b. 6 Dec. 1803 in Bungay, Suffolk, England, youngest daughter of Thomas Strickland and Elizabeth Homer; d. 8 April 1885 at Toronto, Ont.

Susanna Strickland was a member of a 19th-century English family which, like the Brontës, Edgeworths, and Trollopes, was remarkable for the volume of its literary production. Five of the six Strickland girls pursued literary careers and a brother, Samuel*, wrote an autobiographical work late in his life. One of Susanna’s elder sisters, Agnes, was internationally famous for Lives of the queens of England . . . (1840–48), which she wrote with the eldest sister, Elizabeth, and together they produced several other series of biographies of royal and illustrious personages. Although the Strickland name was best known for historical biography, the amazing literary output of the family, spanning eight decades from 1818 to 1895, included works of fiction, poetry, natural history, and autobiography.

Undoubtedly a number of factors combined to bring about the family’s high degree of literary involvement. Some time between the birth of Catharine Parr* in 1802 and Susanna in December 1803, Thomas Strickland moved with his family from London, where he had managed the Greenland Docks, to Suffolk. After living in Bungay for a number of years he bought a 17th-century Flemish-style mansion, Reydon Hall, near Southwold on the Suffolk coast, and moved there at the end of 1808. The location of the mansion in a fertile rural and seaside region was conducive to an interest in flora and fauna, which is revealed in many of the Stricklands’ writings. Susanna, for example, later wrote fondly of the region in Roughing it in the bush as the source of her literary aspirations: “It was while reposing beneath those noble trees that I had first indulged in those delicious dreams which are a foretaste of the enjoyments of the spirit-land. In them the soul breathes forth its aspiration in a language unknown to common minds; and that language is Poetry. . . . Here I had discoursed sweet words to the tinkling brook, and learned from the melody of waters the music of natural sounds.” The “Old Hall” itself, and its library containing major works of history as well as editions of well-known English and classical poets, sparked a fascination for history in members of the family and inspired the writing of poems based on 18th-century models as well as on the works of Scott and Byron. Biographical and autobiographical works by members of the family indicate that the library was well used, mainly because of the pedagogical interest of Thomas Strickland. He and his wife tutored the elder children in the study of history, literature, languages, and mathematics as well as in practical skills, and the older children in turn assumed tutorial responsibilities for the younger girls.

Thomas Strickland re-entered business, becoming a partner in a coach factory in Norwich. His business necessitated residence in that city for part of each year and various members of the family accompanied him during some of these periods. The children, therefore, acquired town as well as rural experience. The experience of the town is reflected in the first book published by a member of the Strickland family, Catharine Parr’s The blind Highland piper and other stories (1818).

There is evidence that it was, curiously, the youngest daughters, Susanna and Catharine, who first entertained literary ambitions. Thomas Strickland’s death in 1818, followed a few months later by the publication of Catharine’s book, brought about both the need for and the possibility of literary careers. Although Thomas bequeathed Reydon Hall to his wife, he left little or no money, and the coach manufactory had failed in the spring of 1818. Circumstances, therefore, urged the Strickland women to supplement the family income by writing for the literary markets available to young ladies during the pre-Victorian period. There was always a demand for children’s books and Susanna and her sisters wrote many such works after the publication of The blind Highland piper. They also contributed stories and poems to the flourishing gift-book and annual trade of the 1820s. But the most significant outlet was magazines for women. It was in such periodicals as the Lady’s Magazine and Museum . . . (1831–37) and the Court Magazine and Monthly Critic (1838–47) that Agnes and Elizabeth first published biographical sketches of royal ladies, and in La Belle Assemblée (1827–28) that Susanna’s sketches of Suffolk life in the manner of Mary Russell Mitford’s Our village (1824–32) appeared. Such early rural pieces served as models for the later Canadian sketches which Susanna wrote for the Literary Garland of Montreal and for her book, Roughing it in the bush.

Another facet of Susanna’s early career that deserves mention is her work for the Anti-Slavery Society. The secretary to the society in the late 1820s was a minor poet, Thomas Pringle, who had resided for a number of years in South Africa. Susanna wrote to Pringle in connection with items she submitted to Friendship’s offering, a gift-book which he edited. Correspondence and friendship followed; indeed, it seems that Pringle became a surrogate father to Susanna. She visited his home in Hampstead (now part of London) in 1830 and in early 1831, and it was there that she met John Wedderburn Dunbar Moodie*, whom she was to marry on 4 April 1831. It was also at Pringle’s that Susanna met former black slaves from the West Indies. The result of such meetings was her two anti-slavery tracts, The history of Mary Prince, a West Indian slave . . . (1831) and Negro slavery described by a negro: being the narrative of [Ashton Warner] . . . (1831). The two pieces, especially the introduction to Negro slavery, relate Susanna’s humanitarian awakening and indicate the source of the Dickensian attention to social injustice to which she gives expression in poems as well as in longer prose works.

Early in 1831, following her visits with the Pringles, Susanna took quarters of her own at 21 Chandor Street, Middleton Square, in the St Pancras area of London, intending to pursue a literary career. There was a temporary break in her engagement to Moodie, her volume of poems was about to be published, and she was writing the anti-slavery pamphlets and book reviews for Pringle. Over the period of a few weeks she became acquainted with many literary and artistic persons in a circle frequented by the Pringles, Leitch Ritchie, and other contributors to the annuals of the day. Her poetic contributions to the annuals were frequent, especially to Forget me not and Friendship’s offering, and she received modest remuneration from their publishers. By 1831 she had enough poems, most of them previously published, to form a volume of 214 duodecimo pages, entitled Enthusiasm; and other poems, in which the theme is the transience of all earthly things. It is a didactic volume which cautions the reader against the pursuit of fame and celebrates the lives of pious persons and their love of God. A significant item in the book is “An appeal to the free,” another account of slavery. Enthusiasm reveals a meditative and emotional temperament, a trait which had been shown in her girlhood and had earlier led to her conversion at the Congregational chapel in Wrentham, Suffolk, a conversion which shocked other more orthodox members of the family.

Following their marriage in 1831, Susanna and her husband lived first in London then in Southwold for a year but poor economic prospects prompted a decision to emigrate to Canada. Undoubtedly Susanna had heard favourable reports of Canada from Samuel, as Catharine’s book, The young emigrants; or, pictures of Canada . . . (1826), makes evident. In a letter to Mary Russell Mitford in 1829 Susanna wrote: “He [Samuel] gives me such superb descriptions of Canadian scenery that I often long to accept his invitation to join him, and to traverse the country with him in his journeys for Government.” According to the novel Flora Lyndsay, Dunbar Moodie preferred to emigrate to South Africa but chose Canada to please his wife. Emotionally, Susanna was most reluctant to leave England; she considered the departure a “fearful abyss” as she recalled it in Roughing it, but the decision was one of “stern necessity.” Not having sufficient wealth to ensure a secure future for their children in England, the Moodies pursued the promise of economic success and high social status in Canada. They sailed from Edinburgh in July 1832 with the first child of the six they were to have. Catharine and her husband had left for Canada earlier the same year. The arrival of the Moodies in the New World was characterized by a comminglement of excitement at the scenic splendour of Lower Canada and the St Lawrence River and apprehension over being “stranger[s] in a strange land.”

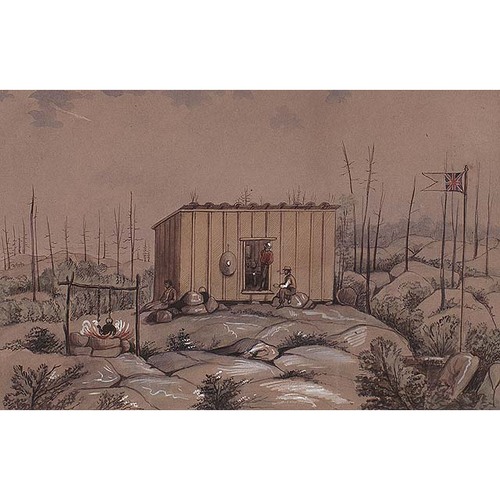

The Moodies bought a cleared farm in Hamilton Township, near Cobourg, Upper Canada, and in so doing chose a different course of settlement from that of other well-known writing families, such as the Traills, Langtons, and Stewarts, all of whom settled, immediately following their arrival, on uncleared land in the Peterborough area. These families, therefore, did not encounter the “Yankee” neighbours who were the source of many frustrating experiences for the Moodies and who also provided the material for subjects in literary sketches. A poor financial investment followed by a decision to sell the farm in 1834 and move to Douro, a backwoods township north of Peterborough, together with the expenses of settling in the backwoods, severely strained the Moodies’ financial resources. The move, however, did have the advantage of placing the family nearer to Samuel, the Traills, and friends. Over the next five years the Moodies again attempted to establish a farm, but were unsuccessful and abandoned farming in late 1839 when Dunbar received an appointment as sheriff of the Victoria District (after 1849 of Hastings County). The family moved to Belleville in January 1840 and it was probably there that Susanna wrote the sketches and stories of backwoods life which eventually appeared as Roughing it in the bush.

It seems likely that their failure as pioneers was as much a result of temperament and personality as of anything else. The difficulties of clearing land and coping with climate, of communications, of finding and keeping agreeable hired persons were as great for the other settlers as for the Moodies, yet the Langtons, Stewarts, Traills, and Stricklands were relatively successful as pioneers and the books written by members of those families evidence a more positive, optimistic, and accepting approach to the pioneering experience than does Roughing it. Susanna’s book opens with a reference to “the Dreadful Cholera” and closes with a metaphor for the backwoods, “the prison-house.” Between the two there is certainly much dwelling on sickness, death, danger, and near-disaster; in other words, the book presents a largely, though not exclusively, negative view of pioneering in Canada. Such an emphasis is, perhaps, more the result of Mrs Moodie’s personality and imagination, of her idea of what had literary appeal, than of her desire to present an account of pioneer life for the information of British gentlemen considering emigration. Although early letters reveal that Susanna was particularly vivacious, she was, according to Catharine Parr Traill, impulsive, “often elated and often depressed.” Catharine observed in her sketch of the early life of Susanna that her sister’s imagination was “romantic, tinged with gloom and grandeur, rather than wit and humor.” Susanna’s book of poems supports that view; it is characterized by warnings against earthly indulgence and consists of largely sombre and ominous verses such as “The deluge,” “The avenger of blood,” and “The destruction of Babylon.” Her fiction too reveals a dark and melodramatic emphasis on miserliness, illegitimacy, malice, murder, and suffering, although ultimately vice is always punished and virtue rewarded. Clearly, the negative incidents and tone of Roughing it are consistent with most of Susanna’s literary production and the character of the book is largely determined by a particular way of seeing the world.

Even under the duress of pioneering Susanna had never entirely relinquished her literary interests. During her early years in Canada she sent poems home for publication in the Lady’s Magazine, a journal with which her sisters were involved. In addition, she had prose and poetry published in the Canadian Literary Magazine (1833) and in the New York Albion (1835), which circulated in Upper Canada. Comments in Roughing it also indicate that some of the poems which appeared in that book were written during residence in the backwoods. Then, in 1838, she began contributing to the Literary Garland in Montreal at the request of its publisher John Lovell*; she became one of the leading contributors to that periodical until its demise in 1851.

It was, however, during the first 15 years of her residence in Belleville that Susanna Moodie was able to devote herself vigorously to her literary career. Undoubtedly the access to better communications and the improved financial circumstances of their life in Belleville gave her the opportunity to develop that career and to augment the family income. She expanded prose pieces which she had written in England and had them published in the Garland as serialized novels; thus “The miser and his son” became Mark Hurdlestone (1853), and “Jane Redgrave” and “The doctor distressed” both formed part of Matrimonial speculations (1854). She submitted poems from Enthusiasm, as well as new ones written in Canada, for publication in the Garland, but her most significant contributions to the periodical were the six Canadian sketches which formed the nucleus of Roughing it. For a period of one year, in 1847–48, she and her husband also edited and contributed the majority of material to the Victoria Magazine, a journal which was intended to perform an educative function for the rising class of mechanics and tradesmen in the colony. The journal had a subscription list of approximately 475 but that was apparently insufficient for Joseph Wilson, the publisher, to continue the enterprise.

In 1852 Susanna began a short but highly satisfactory business relationship with the publisher Richard Bentley of London, England. She contributed to Bentley’s Miscellany from 1852 to 1854; Roughing it was published by his firm in 1852, Life in the clearings followed in 1853, and Flora Lyndsay appeared in 1854, the last work to deal with the Moodies’ Canadian experience. The other works by Susanna published by Bentley, three novels and a volume of novellas, all have English settings and are chiefly expanded versions of previously published materials.

The connection with the Bentley firm was undoubtedly a good one for Susanna Moodie: she had six books published in only three years, in addition to short pieces in the Miscellany, and she received more than £300 for these works. The copyright of Roughing it she sold outright for £50, but she received a further £50 because of its success. The other works were published on agreement that the author would receive half-profits and, except for Matrimonial speculations, each brought her an advance of £50. In addition, she must have received money from New York publishers. Letters to Bentley indicate that she was dealing with G. P. Putnam as well as Dewitt and Davenport for American editions of Roughing it and other works. Between 1852 and 1887 a number of her works were published in the United States by several different publishers.

Her relatively good fortune did not last long. Perhaps Susanna had exhausted herself in the activity of the early 1850s, for there was a long hiatus in her literary career and in her relationship with the Bentley firm. She attempted to resume both in 1865 by again writing to Bentley and submitting work, but the only item to be published was The world before them (1868). The letters to Bentley reveal that this new activity was necessitated by financial exigencies. Dunbar had been forced to resign his shrievalty in 1863 and was unable to gain other employment. He transferred all his property to one of their sons in return for maintenance for himself and his wife for the rest of their lives. Unfortunately Susanna and Dunbar did not get along well with their daughter-in-law, and when the son and his wife emigrated to Delaware the elder Moodies refused to accompany them. They moved to a small cottage outside of Belleville and survived as best they could. Susanna turned again to writing and to another “long neglected art,” the painting of pictures of flowers which she sold for from one to three dollars apiece. These were difficult years for the Moodies; both of them suffered ill health and their other children were either unable or unwilling to assist them. The Moodies lived near Belleville until Dunbar’s death in 1869 after which Susanna lived chiefly with her son Robert in Seaforth and Toronto, although she also boarded with friends in Belleville from 1 Oct. 1870 through 1871. She died in Toronto in 1885 and was buried in Belleville beside her husband.

Susanna Moodie’s three best literary works, Roughing it in the bush, Life in the clearings, and Flora Lyndsay, constitute a chronicle of immigrant and pioneer experience dealing with all phases of the process from the decision to leave England to establishment in a Canadian town. Flora Lyndsay, the first chronologically, was the last of the three to be published, and is the third in order of quality and interest. It deals, in the form of a loosely structured novel, with the initial discussions of emigration by a young married couple, and continues through the final decision and the crossing. In a letter to her son-in-law, written about the time of the publication of the Canadian edition of Roughing it in 1871, Mrs Moodie observes that Flora “is Canadian and the real commencement of Roughing It.” Although the book conveys some sense of the vicissitudes of emigration as well as the perils and tedium of the crossing, it does not dwell on these things nor does it have a strong story line. It consists chiefly of sketches and anecdotes about a large gallery of characters, ranging from those based on Mrs Moodie’s neighbours and advisers in Suffolk to her fellow passengers and the one-eyed, alcoholic captain of the brig Anne on which they sailed for Quebec. That Susanna delighted in the study of human beings and was able to get them to talk about themselves is clearly evident in Flora Lyndsay as well as in the other two books of the trilogy; she listened and observed carefully and was able to capture humour and pathos in her reproductions. Included in Flora Lyndsay is a long story, almost a novel within a novel, based on Suffolk people; this was written by Susanna on the Anne when it was becalmed for three weeks off Newfoundland, at which time food rations became low. Unfortunately, the plot and style of the story clash with the air of authenticity and simplicity of the character sketches, for it bears an excess of pretentiousness, sentimentality, and didacticism, being a story of greed, murder, and repentance.

Roughing it in the bush is superior to any of Susanna’s other works and, indeed, its quality has ensured an enduring recognition of Susanna Moodie as an important figure in Canadian literary history. Much attention has been given to the book, and it has been published in numerous editions in Britain and the United States as well as in Canada. In the 19th century it was admired by reviewers in all three countries for the lively style and humour with which it depicted colonial characters, backwoods customs, domestic practices, and natural surroundings. In the 20th century it has functioned as a touchstone for Canadian literary critics, being variously referred to as a valuable historical document, an early example of local colour or realistic fiction, and an expression of the romantic sensibility in 19th-century Canada. In the latter half of the 20th century, as more thorough and serious examinations of Canadian literature are being made, analyses are revealing hitherto ignored complexities of structure and style, and the personality of its author, as reflected in the book, is being seen as representative of persistent and deeply rooted elements in the collective experience of Canadians.

Although it is unlikely that the same richness will be discovered in Life in the clearings, as yet it has been neglected by literary historians and critics. The circumstances of the latter book were different from Roughing it: a request by Bentley for an account of life in the towns and of a trip to Niagara Falls to be used as a motif around which to centre a series of sketches and essays on colonial society. As a result, it resembles the books produced by such visiting Englishwomen as Harriet Martineau and Frances Trollope, and like their books it presents observations of the institutions and customs which were both reflecting and helping to shape North American society and culture. Although it contains some of the character sketches meant for Roughing it, it concentrates on the characteristics of a province which has recently achieved responsible government. There is repeated notice of the people’s sense of liberty, their industrious habits, and their mechanical genius. The frequency of patriotic and optimistic statements probably indicates an effort by the author to stress that she was not anti-Canadian, as many readers of Roughing it had thought because of her cautionary statements to British gentlemen about the hazards of emigration.

Roughing it, unlike the other books, was generated by the traumatic experiences of emigration and backwoods life, and manifests, in its complexity, the tensions in the intellectual, emotional, and imaginative life of its author. It seems likely that it will continue to challenge future critics to new interpretations.

Susanna [Strickland] Moodie wrote Enthusiasm: and other poems (London, 1831); Flora Lyndsay: or, passages in an eventful life (2v., London, 1854); Geoffrey Moncton: or, the faithless guardian (New York, [1855]); Hugh Latimer; or, the school-boys’ friendship (London, 1828); Life in the clearings versus the bush (London, 1853); Mark Hurdle stone, the gold worshipper (2v., London, 1853); Matrimonial speculations (London, 1854); Roughing it in the bush; or, life in Canada (2v., London, 1852); The world before them: a novel (3v., London, 1868). With her sister, Catharine Parr Traill, she wrote The little prisoner; or, passion and patience: and Amendment; or, Charles Grant and his sister (London, 1828). Items by Susanna Moodie appear in Ackermann’s juvenile forget me not: a Christmas, New Year’s, and birth-day present, for the youth of both sexes, M.DCCCXXXII, ed. Frederic Shoberl (London, [1832]); Forget me not; a Christmas, New Year’s, and birth-day present for MDCCCXXXI, ed. Frederic Shoberl (London, [1831]); The juvenile forget me not: a Christmas and New Year’s gift, or birthday present for the year 1831, ed. [A. M. ] Hall (London, [1831]); Marshall’s Christmas box, a juvenile annual (London, 1832). For further editions and other publications by Susanna Moodie see C. P. A. Ballstadt, “The literary history of the Strickland family . . .” (phd thesis, Univ. of London, 1965).

A manuscript of C. P. [Strickland] Traill, “A slight sketch of the early life of Mrs. Moodie,” is held by T. R. McCloy in Calgary. British Library (London), Add. mss 46653: ff.260–63; 46654; 46676: f.11. M. A. Fitzgibbon, “Biographical sketch,” C. P. Traill, Pearls and pebbles; or, notes of an old naturalist . . . (Toronto, 1894), x-xiii. J. M. Strickland, Life of Agnes Strickland (Edinburgh and London, 1887), 4–5. A. Y. Morris, Gentle pioneers: five nineteenth-century Canadians (Toronto and London, 1968). Clara Thomas, “The Strickland sisters: Susanna Moodie, 1803–1885, Catharine Parr Traill, 1802–1899,” The clear spirit: twenty Canadian women and their times, ed. M. Q. Innis (Toronto, 1966), 42–73. W. D. Gairdner, “Traill and Moodie: the two realities,” Journal of Canadian Fiction (Fredericton), 1 (1972), no.2: 35–42. R. D. MacDonald, “Design and purpose,” Canadian Literature (Vancouver), 51 (winter 1972): 20–31. T. D. MacLulich, “Crusoe in the backwoods: a Canadian fable?,” Mosaic (Winnipeg), 9 (1975–76), no.2: 115–26. W. H. Magee, “Local colour in Canadian fiction,” Univ. of Toronto Quarterly (Toronto), 28 (1958–59): 176–89.

Cite This Article

Carl P. A. Ballstadt, “STRICKLAND, SUSANNA (Moodie),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 1, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/strickland_susanna_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/strickland_susanna_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Carl P. A. Ballstadt |

| Title of Article: | STRICKLAND, SUSANNA (Moodie) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | April 1, 2025 |