Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

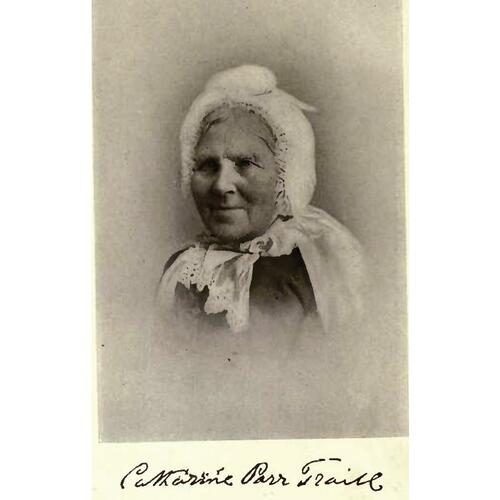

STRICKLAND, CATHARINE PARR (Traill), settler, author, teacher, and naturalist; b. 9 Jan. 1802 in Rotherhithe (London), England, fifth daughter of Thomas Strickland and Elizabeth Homer; d. 29 Aug. 1899 at Lakefield, Ont.

Though Catharine Parr Strickland’s life embraced nearly the entire 19th century and though she spent nearly 70 years in Canada, the roots of her values, beliefs, and interests belong to the rural Suffolk of her girlhood. Not long after her birth in Kent, her father, Thomas Strickland, retired as manager of the Greenland Docks on the Thames and removed his family to Norwich (in Norfolk), hoping to reduce his business involvements and to find a more congenial climate for his family and for the gout from which he suffered. A man of wide intellectual interests, he also wished to undertake the education of his daughters (of whom there were six by 1803) and to purchase an appropriate home for his growing family. From 1804 to 1808, while he maintained a small residence in Norwich in conjunction with his new business interests, he rented Stowe House, a farm in Suffolk, near Bungay, overlooking the pastoral Waveney valley. It was here that Catharine’s most vivid memories of childhood were formed. She recalled in particular fishing with her father in the Waveney while being read to and reading from his copy of Izaak Walton’s The compleat angler. “The dear old Fisherman,” as she told author William Kirby* in 1895, had helped when she was a child “to form my love of Nature and of Natures God.”

At Stowe House and later at Reydon Hall, an Elizabethan manor-house near Southwold on the Suffolk coast, which Thomas Strickland purchased in 1808, the children were taught and stimulated by their father. He insisted that his daughters be schooled in such subjects as geography, history, and mathematics, all of which he oversaw; his wife took charge of their development in the traditional feminine skills. At the same time he emphasized industry, observation, and self-reliance beyond the classroom. He encouraged the girls to make their own toys, raise their own pets, and tend their respective gardens. As they matured, he enjoyed involving them in arguments on contentious points, encouraging them to think through their responses. Such were his knowledge and bearing that his children customarily took his views as authority.

By the time Thomas Strickland purchased Reydon Hall he had fathered two sons and had reached the zenith in his social ambitions. Yet the effect on his health of the damp North Sea climate and the dilapidated state of the hall in combination with business pressures in Norwich kept him away from Reydon for extensive periods. The children were frequently thrown much upon their own resources and the older sisters, Elizabeth and Agnes (who would later achieve considerable fame as biographers of British royalty) along with Sara (the only one of the six Strickland girls who did not write), were often put in charge of the younger five.

In May 1818 life at Reydon Hall changed dramatically. Thomas Strickland died, his estate significantly undermined by business reversals. His wife and children were thus left with scant means to maintain the hall and its grounds or to promote their social position. It was in this context that the resourcefulness of young Catharine clearly emerged. A friend of her father’s, on reading a manuscript by the 15-year-old girl, edited it for her and took it to a London publisher. The tell tale: an original collection of moral and amusing stories appeared anonymously in 1818, the first of a flood of literary materials from the five scribbling Strickland sisters. (Catharine later recalled, perhaps erroneously, that her first title was The blind Highland piper and other tales, but because no such book has been found and because “The blind Highland piper” is included in The tell tale the case is stronger for the latter.) What had been a sisterly hobby and a way of beguiling dull Suffolk winters became initially a means of coping with the genteel poverty into which the Stricklands had slipped. Later, for the spinster sisters in England – Eliza, Agnes, and Jane Margaret – as well as for Catharine and Susanna* in Upper Canada, the hobby became a kind of career.

In the years before her emigration Catharine kept busily at work writing not only for the burgeoning adolescent book trade of pre-Victorian London but also for the newly popular annuals and gift-books. In the mode of Thomas Day, Maria Edgeworth, and Sarah Trimmer, she typically sought to present clear and important moral instruction by means of didactic stories or autobiographical reminiscence. Although the ephemeral nature of many of her works and her practice of publishing anonymously, occasionally in collaboration with her sisters, make it difficult to establish an exact record of her early books, her own accounts, made in old age, and textual evidence provide assurance of some ten published between 1819 and 1831. Titles reveal a good deal: Disobedience; or, mind what Mama says (1819); Little Downy; or, the history of a field mouse: a moral tale (1822); The keepsake guineas; or, the best use of money (1828); and Sketch book of a young naturalist; or, hints to the students of nature (1831). Perhaps the most interesting of these books is The young emigrants; or, pictures of Canada; calculated to amuse and instruct the minds of youth (1826). In it, Catharine drew upon her fascination with Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, travel books about the Canadas, including those of John Howison*, and the letters of friends who, like her younger brother Samuel*, had immigrated there in the 1820s. The comment of one of her young emigrants – “I sometimes think I should like to spend my life in exploring the face of this astonishing country” – vividly suggests Catharine’s capacity to find stimulation and involvement in the idea of new experiences, however challenging or demanding they might be.

The most emotional event of her quiet Reydon years was her two-year engagement to Francis Harral, the son of a prominent writer and editor in Suffolk and London. When it was broken off in 1831 she took a consolatory tour with a wealthy aunt, visiting Waltham Cross, Bath, Cheltenham, and Oxford before returning to London at year’s end. It was likely early in 1832 that she met Lieutenant Thomas Traill, a widowed Scot who was, like his friend John Wedderburn Dunbar Moodie*, a half-pay officer formerly in the 21st Foot. Their brief courtship was sufficient to convince her, as she wrote to a friend, that she was “willing to lose all for the sake of one dear valued friend and husband to share with him all the changes and chances of a settler’s life.” Despite considerable family opposition they married at Reydon parish church on 13 May 1832.

Traill, who had two sons then living in Scotland, was not considered a suitable match for Catharine. Her sister Agnes, in letters to Susanna over the next two decades, continued to lament Catharine’s choice of husband and to see him as the author of her increasing difficulties in Canada. What Agnes could not understand was Catharine’s spirited determination both to marry and to start a new life once the opportunity presented itself. Having before her, however, the example of her brother and several friends and being well aware of Susanna’s thoroughly developed plans to emigrate, she did not hesitate to act.

For his part, Traill also welcomed a fresh start, one in which he might parlay land-grant entitlements and cheap land prices in Upper Canada into a comfortable income attained in a leisurely manner appropriate to his class. Traill himself was personally in debt, and Westove, the family estate in the Orkneys to which he was heir, was so encumbered with debt as to offer few prospects. At the same time, lacking the means to provide either a home or an education for his sons, he relied on the kindness of his deceased wife’s family, the Fotheringhames, of Kirkwall, to do so. After the wedding the couple visited Scotland, in particular Kirkwall and Westove, and then departed from Greenock in early July 1832 aboard the brig Laurel. Thomas Traill never saw his sons again.

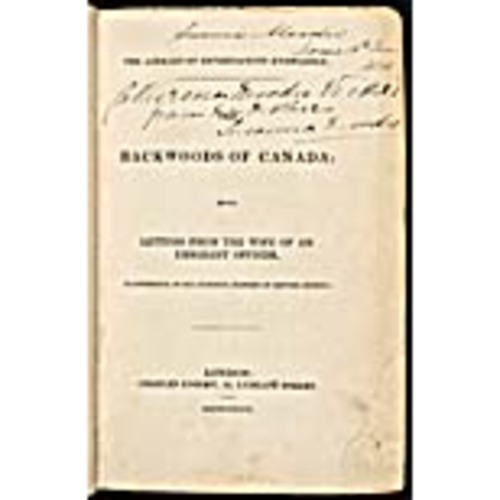

The events of the Traills’ first three years in the Upper Canadian bush are recounted in Catharine’s best known book, The backwoods of Canada: being letters from the wife of an emigrant officer, illustrative of the domestic economy of British America (London, 1836). Maintaining her practice of authorial anonymity, she drew together 18 “letters,” divested of familial chit-chat and enriched by extensive passages of descriptive narrative, to tell the story of her emigration, settlement, and cheerful adjustment. Retrospective observations in these entries make it clear that Catharine had organized and rewritten them with particular purposes and patterns in mind. She or her sister Agnes then placed the manuscript with Charles Knight. Publisher to the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, Knight was, according to Catharine, the third publisher to see the manuscript.

The backwoods is clearly much more than a personal memoir meant only for family and friends. It offers a practical guide for English gentlewomen faced, as many were in the 1830s, with the formidable prospect of uprooting and emigration. Describing the travels, house-building, and land-clearing of the Traills, it consistently measures Canadian experience through the lens of respectability, social class, and good taste, and in terms of interests congenial to women of similar background. Mrs Traill finds much to disturb her eye and her values, especially in her early letters. At the same time she characteristically seeks to adjust her expectations without compromising her treasured English middle-class principles. Accordingly, The backwoods reflects not only the even tenor of her personal disposition but also what Carl Ballstadt calls “a rhetoric of balance.” Subjectivity and objectivity, Old World expectations and New World exigencies, the picturesque and the actual are set in opposition in an effort not to belittle Canada but to make clear the kinds of adjustment, effort, and resolve that were necessary if one was to adapt to Canada’s primitive and demanding circumstances.

The structure of The backwoods also emphasizes adaptation. Arranged chronologically, the letters take the Traills through a series of difficulties and disappointments out of which they emerge more attuned to their new circumstances, comforted by the success achieved in those trials. Modelled on such books as Robinson Crusoe and John Bunyan’s The pilgrim’s progress, it bespeaks the quiet triumph of the English Protestant spirit not only in meeting harsh conditions cheerfully and with curiosity but also in carrying forward the banner of Christianity and civilization. Among the literary undertakings of Upper Canadian pioneers, The backwoods ranks with Susanna Moodie’s Roughing it in the bush . . . (2v., London, 1852), to which it is textually related and with which it has often been compared. Other notable writings by pioneer women, such as Frances Stewart [Browne*]’s Our forest home . . . (Toronto, 1889) and Anne Langton’s A gentlewoman in Upper Canada . . . (Toronto, 1950), although not prepared with a view to publication, lack both the developed sense of literary self and the attentiveness to audience that characterize Traill’s and Moodie’s work.

The inadvertent irony of The backwoods lay in the reversal of the Traill family fortunes within a few years of the book’s publication. Their emigration had been eased by Catharine’s younger brother Samuel, who arranged for their land grant near his own property in Douro Township, near present-day Lakefield, and provided them with a home while their log cabin was being built. Thomas Traill had no experience as a farmer and found relative isolation in the bush uncongenial to his social inclinations. Late in The backwoods Catharine notes, perhaps without then realizing the consequences, that her husband was undergoing “the same sort of depression on the spirits as a nervous fever.” As early as 1835 he put the Douro property up for sale. He finally sold it in 1839, taking his growing family to Ashburnham (Peterborough), to be closer to such like-minded friends as Dr John Hutchison and Thomas Alexander Stewart*. Despite making a number of transactions, Traill had little sustained success as a dealer in properties. Increasingly he found himself besieged by debts, some resulting from his own misjudgements, others stemming from legal claims upon his father’s beleaguered Orkney estate. During the 1840s he was forced to move his family often. Such was their destitution by the spring of 1846 that an eccentric English friend, the Reverend George Bridges, who much admired Catharine and her writing, made available to them rent-free his fortress-like home on Rice Lake, Wolf Tower. A year later they rented a nearby property, Mount Ararat, before purchasing Oaklands, a farm above Rice Lake’s south shore, where they lived from May 1849 until it was destroyed by a devastating fire on 26 Aug. 1857.

Between 1833 and 1847 Catharine gave birth to nine children, two of whom died in infancy in the early 1840s. Illnesses and pregnancies kept her inactive a great deal of the time. To alleviate financial strains she briefly tried schoolteaching in Peterborough and she continued to write stories, sketches of nature, and autobiographical narratives, desperately searching for markets in England, the United States, and the Canadas. Agnes placed some of her Canadian pieces in such London magazines as Chambers’ Edinburgh Journal, the Home Circle, and Sharpe’s London Magazine. Catharine also wrote occasionally for John Lovell’s Montreal magazine, the Literary Garland, to which her sister Susanna was a regular contributor.

Life at Oaklands in the 1850s was an increasingly difficult struggle marked not only by deaths, illnesses, lack of firewood, and crop failures, but also by the incapacitating bouts of depression suffered by Thomas. Whatever role her husband’s weaknesses played in the family’s misfortunes, however, Catharine seldom complained. She remained loyal to him and to their marriage. Fortunately, she continued to have some success in finding outlets for her writing. Agnes made a contract with a London publisher, Arthur Hall, Virtue, and Company, for Catharine’s children’s story Canadian Crusoes: a tale of the Rice Lake plains (1852), in which three young offspring of pioneers heroically survive two years on their own in the unsettled wilderness north of Lake Ontario. Hall and Virtue also published another book aimed at the children’s market, Lady Mary and her nurse; or, a peep into the Canadian forest (1856), the text evolving from the sketches Catharine wrote originally for a Canadian magazine, the Maple Leaf (Montreal), in 1853. As she was to comment in a letter of 1896, “My role in writing has ever been for the young. I rarely aspire to any higher style.”

There were, however, other useful and adult-oriented avenues she followed. The success of The backwoods – it went through several reimpressions and editions in the 1830s and 1840s – led her to attempt various kinds of sequels. One, entitled “Forest gleanings,” comprised sketches drawn from her backwoods and Rice Lake experiences. It appeared in 13 instalments in Toronto’s Anglo-American Magazine in 1852–53 but, despite its considerable value and interest, was not brought out in book-form. No assessment of Catharine’s overall literary achievement will be possible until readers become better versed in the considerable amount of work she wrote from the 1830s to the 1850s.

Another successful publishing venture, a cobbling together of narrative sequences, quoted extracts, recipes, and practical advice, capitalized on her established reputation as an adviser to emigrant women. The female emigrant’s guide, and hints on Canadian housekeeping was published in parts in Toronto in 1854–55 by Thomas Maclear, reappearing in 1855 under the title The Canadian settler’s guide. At the same time in a magazine called the Horticulturist (Albany, N.Y.) she found, albeit briefly, an outlet for her writings on flowers and the natural world.

In The backwoods Catharine had devoted an entire letter to descriptions of Canadian flowers and the utility of botanical knowledge, regretting that she had not studied flower-painting before emigrating. Throughout her Canadian life, in fact, she collected and studied specimens of flowers, grasses, and ferns, keeping careful journal notes and, with her daughters, creating arrangements of pressed flora for sale or competition or as gifts. Her collection and notes were among the few items she managed to save from the fire in 1857. All her early efforts to locate a publisher or champion for her botanical work were frustrated in one way or another. As she told her friend Frances Stewart in a letter of 1862, she was “the poor country mouse” when it came to exhibitions and negotiations.

It was not, however, until years after Thomas Traill’s death on 21 June 1859, when she was at last established in the Lakefield cottage, Westove, arranged for her by Sam Strickland, that she had the opportunity to collaborate with her widowed niece Agnes Dunbar FitzGibbon, daughter of Susanna Moodie and like her mother a skilled illustrator of flowers. Agnes not only taught herself lithography but secured publication by John Lovell in 1868 of Canadian wildflowers, to which she contributed the illustrations and Catharine the text. The book was sold by subscription and went through at least four editions. The collaboration resumed years later when, in 1884, Agnes, then Mrs Chamberlin and settled in Ottawa, undertook negotiations for publication there of Catharine’s fullest nature work, Studies of plant life in Canada; or, gleanings from forest, lake and plain (1885). A far more interesting and approachable book than its scientific title would seem to suggest, it led a friendly authority in Ottawa, James Fletcher*, to praise her descriptive skills as “one of the greatest botanical triumphs which [anyone] could achieve.” Carl Clinton Berger has called the book “a splendid anachronism,” directing attention not only to the delays in publication but to the spirited approach that characterizes Traill’s inventories and her floral biographies. Though she was not a critical scientist she brought a passion to her study that has won her considerable admiration. Under less adverse circumstances her work might have been published earlier, thereby earning her a more significant place in the evolution of botanical studies in Canada.

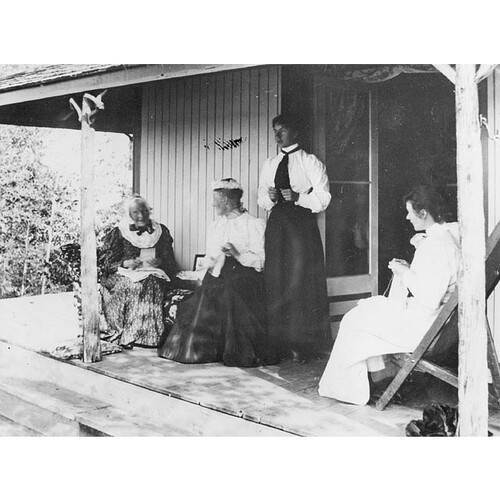

Catharine lived out her long life quietly in Lakefield, watched over by her daughter Katharine and granddaughter Katharine Parr Traill. By then, five of Catharine’s children had died. Another daughter, Anne, and her family lived near by; two sons, William and Walter, had settled in western Canada.

Often plagued by illnesses and increasingly constrained by deafness, she continued to write and to seek publishers. She was in her nineties when she published with William Briggs* her last two books, Pearls and pebbles; or, notes of an old naturalist . . . (Toronto, 1894) and Cot and cradle stories (Toronto, 1895), helped in each case by Agnes FitzGibbon’s daughter, Mary Agnes. Drawing on material from her entire career as a writer, the two collections stress Mrs Traill’s abiding faith in God’s unfathomable but benevolent wisdom and in the refreshing lessons to be learned from the natural world. Plans for Briggs to publish a third book, the first Canadian edition of The backwoods, corrected and expanded by Traill herself, were not realized.

Among the tributes Catharine Parr Traill received in her later years were recognition by historical societies in Toronto and Peterborough, a pension from the Royal Literary Fund in England, and a testimonial organized by her old friend Sir Sandford Fleming*, which brought her $1,000 in 1898. Never far removed from the strains of financial worries during most of her lifetime, Mrs Traill was not only grateful for so substantial and unexpected a gift but also pleased by “the assurance” it gave her “that in my small way I have served my beloved Sovereign’s noble dominion of Canada.”

[The most comprehensive listing of works by the subject is that included in Carl P. A. Ballstadt’s study “Catharine Parr Traill (1802–1899),” Canadian writers and their works, ed. Robert Lecker et al., intro. George Woodcock (9v. to date, Toronto, 1983– ), fiction ser., 1: 149–93. An additional title appears in Rupert Schieder, “Catharine Parr Traill: three bibliographical questions,” Biblio. Soc. of Canada, Papers (Toronto), 24 (1985): 8–25. Schieder’s edition of her Canadian Crusoes: a tale of the Rice Lake plains ([Ottawa], 1986), prepared for the Centre for Editing Early Canadian Texts, provides useful background information.

The Traill family collection at the NA (MG 29, D81) is the fullest archival source of Catharine’s journals, letters, notebooks, and memorabilia. Valuable source material is also found in letters from several of the Strickland sisters in the Glyde coll. at the Suffolk Record Office, Ipswich Branch (Ipswich, Eng.), a microfilm copy of which is available among the Susanna Moodie papers at the NA (MG 29, D100); Traill’s letters to Frances [Browne] Stewart among Stewart’s papers in the MTRL; and the P. H. Ewing coll. of Moodie–Strickland–Vickers–Ewing family papers, recently acquired by the National Library of Canada (Ottawa).

The author of this biography is currently preparing bibliographies of the works of Catharine and Susanna; as well, he is at work on editions of the letters of the two sisters, in collaboration with Carl Ballstadt and Elizabeth Hopkins. The first volume resulting from this project, a collection of Susanna’s correspondence entitled Susanna Moodie: letters of a lifetime, was published in Toronto in 1985. m.a.p.]. The valley of the Trent, ed. and intro. E. C. Guillet (Toronto, 1957). DNB. Morgan, Sketches of celebrated Canadians. Oxford companion to Canadian lit. (Toye). C. P. A. Ballstadt, “The literary history of the Strickland family . . .” (phd thesis, Univ. of London, 1965); “Lives in parallel grooves,” Kawartha heritage: proceedings of the Kawartha conference, 1981, ed. A. O. C. Cole and Jean Murray Cole (Peterborough, Ont., 1981), 107–18. C. [C.] Berger, Science, God, and nature in Victorian Canada (Toronto, 1983). Sara Eaton, Lady of the backwoods: a biography of Catharine Parr Traill (Toronto and Montreal, 1969). Marian [Little] Fowler, The embroidered tent: five gentlewomen in early Canada . . . (Toronto, 1982), 55–87. Lit. hist. of Canada (Klinck et al.; 1976), vols.1–2. Norma Martin et al., Gore’s Landing and the Rice Lake Plains (Gore’s Landing, Ont., 1986). A. Y. Morris, Gentle pioneers: five nineteenth-century Canadians (Toronto and London, 1968). G. H. Needler, Otonabee pioneers: the story of the Stewarts, the Stricklands, the Traills and the Moodies (Toronto, 1953). M. [A.] Peterman, “Catharine Parr Traill,” Profiles in Canadian literature, ed. J. M. Heath (4v., Toronto and Charlottetown, 1980–82), 3: 25–32; ‘“Splendid anachronism[s]’: the record of Catharine Parr Traill’s struggles as an amateur botanist in nineteenth-century Canada” (paper presented at Univ. of Ottawa symposium on 19th-century Canadian women writers, 1988); “A tale of two worlds – from there to here,” Kawartha heritage, 93–106. Lorne Pierce, William Kirby: the portrait of a tory loyalist (Toronto, 1929). Clara [McCandless] Thomas, “The Strickland sisters: Susanna Moodie, 1803–1885, Catharine Parr Traill, 1802–1899,” The clear spirit: twenty Canadian women and their times, ed. Mary Quayle Innis (Toronto, 1966), 42–73. Suzanne Zeller, Inventing Canada: early Victorian science and the idea of a transcontinental union (Toronto, 1987). “Collaborative sleuthing in Canadian literature,” York Univ., Robarts Centre for Canadian Studies, Bull. (North York [Toronto]), 4 (1987–88), no.1. W. D. Gairdner, “Traill and Moodie: the two realities,” Journal of Canadian Fiction (Fredericton), 1 (1972), no.2: 35–42. David Jackel, “Mrs. Moodie and Mrs. Traill, and the fabrication of a Canadian tradition,” Compass (Edmonton), no.6 (1979): 1–22. Ute Lischke-McNab and David McNab, “Petition from the backwoods,” Beaver, outfit 308 (summer 1977): 52–57. T. D. MacLulich, “Crusoe in the backwoods: a Canadian fable?” Mosaic (Winnipeg), 9 (1975–76), no.2: 115–26. M. [A.] Peterman, “Agnes Strickland’s sisters,” Canadian Literature (Vancouver), no.121 (summer 1989) (forthcoming).

Cite This Article

Michael A. Peterman, “STRICKLAND, CATHARINE PARR (Traill),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/strickland_catharine_parr_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/strickland_catharine_parr_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michael A. Peterman |

| Title of Article: | STRICKLAND, CATHARINE PARR (Traill) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |