Source: Link

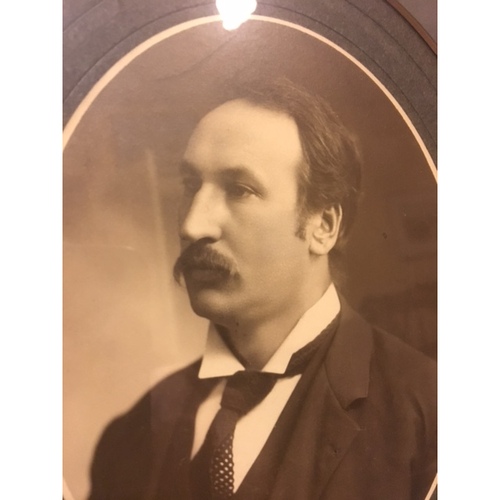

WOOD, SAMUEL THOMAS, journalist, writer, and reformer; b. 16 Jan. 1860 in Wollaston Township, Upper Canada, son of English immigrants Samuel Wood and Catherine Gibson; m. first 19 Sept. 1888 Frances Spinks Dwyer (d. 25 Dec. 1911) in Toronto, and they had two sons; m. there secondly 3 Feb. 1914 Dora Spears; d. 6 Nov. 1917 in Toronto and was buried in Belleville, Ont.

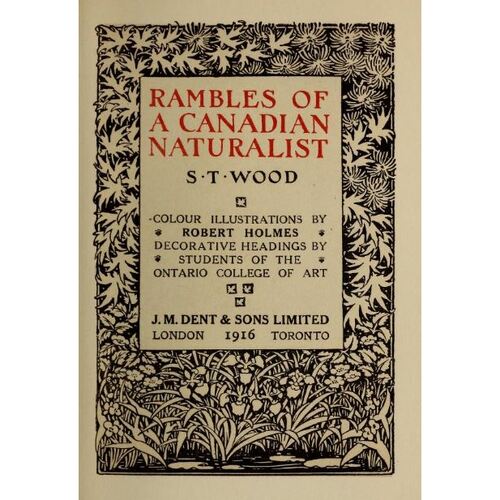

Samuel Thomas Wood spent his earliest years on a backwoods farm; he was said to have been rocked in a birchbark cradle and to have heard wolves howling at night. When he was five his family moved to Belleville, where he attended public and high schools and a business college. He lived for a year in Peterborough before settling in Toronto in 1885. He worked as a steamfitter and came into contact with an ebullient group of social reformers, or, as he later called them, “social regenerators” and “cranks,” “socialists, anarchists, single taxers, Christian scientists,” who “talk freely of all problems, from the cutting of bay ice to the passing of a resolution on the destiny of the North American continent.” Wood was an ardent convert to Henry George’s single tax, which he propounded at weekly meetings of the Sandpaper Club and from a soapbox at gatherings in public parks. With journalist Thomas Stewart Lyon (brother-in-law of his first wife and a lifelong friend) and William Alexander Douglass*, both single-taxers, he founded the Toronto Anti-Poverty Society around 1887. Wood was equally active in the Young Men’s Liberal Club in Toronto, where he met John Stephen Willison*, editor of the Globe. Willison hired him as a mechanic in 1891 and then as a reporter and special correspondent with assignments that took him across the country. Subsequently, Wood contributed to the Globe a column of “Impressions” on the flotsam and jetsam of life (which he signed Uncle Thomas), a short daily feature entitled “Lessons in economics,” and, most notably, essays on natural history, some of which were collected in Rambles of a Canadian naturalist (Toronto, 1916).

Unlike others whose interest in social questions was ignited by the ideas of Henry George but who passed on to different reforms, Wood never gave up on the single tax. He was self-taught in economics, had immersed himself in the major works of the classical liberal school, and adhered to the notion of economic laws as elemental, natural laws. There is a conciseness, clarity, and deceptive simplicity in his Primer of political economy: an explanation of familiar economic phenomena, leading to an understanding of their laws and relationships (Toronto, 1901), in which he brought everything within the comprehension of elementary school students. In describing the making of a pair of shoes, Wood highlighted the interdependence of individuals and the beneficence of the invisible hand. Though he refrained from editorializing on the single tax, his account of economic activity leads inevitably to it. He justified taxing the rental value of land on the grounds that all had a moral right to share in nature’s wealth. He also saw the single tax as a way of simplifying and purifying economic life: it would discourage state interference in the economy and make all other taxes, including the tariff, unnecessary. In his economic thinking Wood remained a liberal of the laissez-faire school and thought little of efforts to amend its truths. Of the English economist and reformer Arnold Toynbee, Wood wrote that he had done good in his settlement-house work in London’s East End but he had not done right in deflecting economics into a relativist, historical direction, away from the law that with freedom to produce and exchange and to sell labour and all things saleable, every useful member of the community obtained the exact value of services rendered.

Wood was most widely recognized through his nature writing, not his economics. An admirer of Henry David Thoreau and Walt Whitman and a friend of such local field naturalists as William Brodie*, Wood rejoiced in rambling around the Toronto suburbs, ravines, and lakeshore and in observing the habits of birds and the structures of flowering plants. Like the leading American nature writer John Burroughs, Wood focused on nature on a small scale and in minute detail – the composition of the pitcher-plant, for example, or the arrangement and appearance of eggs in the nest of a song sparrow. On the latter he wrote: “The five eggs were carefully and regularly placed with their small ends downward. They were pale, almost white, with the rich brown spots crowding and clustering on the larger ends as if they were freckled by exposure to the sun.” Wood sought to draw out the larger implications of what he witnessed. Though in general he did not personalize birds, or celebrate God’s handiwork in nature (as Catharine Parr Traill [Strickland*] had done), his readers were made aware of the immanence of a creative force in the natural world that affected humanity as well as animal life. Wood’s was a post-Darwinian world – of nature’s indifference to human concerns, of inexorable laws of change, death, and rebirth, of struggle and conflict.

For all this emphasis on strife, and the precariousness of the lives of birds, the dominant tone of Wood’s essays is one of kindliness and kinship. His writings are enlivened by an attractive sense of humour, as when he remarked that “the Dandelion can be loved for the enemies it has made,” or, after explaining the habit of cowbirds of depositing their eggs in the nests of other species, described two chipping sparrows raising and ceaselessly feeding a pretended offspring much larger than themselves.

Wood’s nature column gained a large following, including Sir Wilfrid Laurier who confessed he missed it greatly when it was temporarily interrupted. Encouraged by the reception of Rambles, Wood was preparing a second volume when he fell ill while on holiday at Bon Echo, an avant-garde summer community in eastern Ontario dedicated to Whitman. He died – emaciated – of cancer of the liver.

Those who knew Wood all commented on his serenity, good temper, and gentle wit. Melvin Ormond Hammond, who edited the magazine section of the Globe, was struck by Wood’s “remarkable dual personality” expressed in the park oratory on the single tax and the amiable nature essays. “His room at the office,” Hammond added, “was a small museum, and when . . . the caretaker once disturbed a live snake in an old biscuit tin, he vowed never to clean the room again, which was quite satisfactory to Mr. Wood.” This unconventionality was evident too in his unfashionable black broad-brimmed hat and his aversion to formality: he would have been the very last person to present himself for election to public office. Wood was tall, sturdy in appearance, and abstemious. He left an estate of just over $9,000; about half was represented by his house and most of the remainder was in bonds and cash. His personal effects were estimated at $20; his royalty agreement with J. M. Dent and Company for Rambles was deemed of no market value, a fact which would no doubt have bemused him.

Wood’s reputation rested on his nature writing and he was later judged “a well-informed and enthusiastic field-naturalist and an essayist of literary ability.” It was not until the counter-culture of the 1970s intensified an interest in the antecedents of social criticism that Wood came to figure as a minor character among the late Victorian social regenerators.

The chief source of information on Wood is A tribute to Samuel T. Wood, privately issued after his death ([Toronto], 1917). It contains reminiscences of him by Sir John Willison, Arthur Hugh Urquhart Colquhoun*, and others, and reproduces obituaries and appreciations from several newspapers, including the Globe of 7 Nov. 1917. Biographical details are also provided by the record of Wood’s marriages (AO, RG 80-5-0-165, no.14318 and RG 80-5-0-693, no.1794) and the sketch in Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell), vol.1. The J. L. Baillie papers in the Univ. of Toronto Library, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library (ms coll. 127) include a thin file of press clippings concerning him (box 36).

Apart from the titles mentioned in the text, Wood’s publications include two essays in the Canadian Magazine: “The regenerators,” 1 (March-October 1893): 64–67 (issued under his pen-name Uncle Thomas), and “Social amelioration: the contrast between doing good and doing right,” 11 (May-October 1898): 461–66. He also reprinted A primer on political economy as How we pay each other: an elementary reader in the simple economics of daily life (Toronto, 1916).

The wider context of Wood’s reformist circle and the single-tax movement is traced in Ramsay Cook, The regenerators: social criticism in late Victorian English Canada (Toronto, 1985), and in G. H. Homel ‘“Fading beams of the nineteenth century’: radicalism and early socialism in Canada’s 1890s,” Labour (Halifax), 5 (1980): 7–32. The conventions of the natural history essay are set out in P. M. Hicks, The development of the natural history essay in American literature (Philadelphia, 1924); L. L. Merrill, The romance of Victorian natural history (New York, 1989), c.6; and Alec Lucas, “Nature writers and the animal story,” in Literary history of Canada: Canadian literature in English, ed. C. F. Klinck et al. (2nd ed., 4v., Toronto, 1976–90), 1: 380–404.

Cite This Article

Carl Berger, “WOOD, SAMUEL THOMAS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 26, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wood_samuel_thomas_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wood_samuel_thomas_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Carl Berger |

| Title of Article: | WOOD, SAMUEL THOMAS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | April 26, 2025 |