Source: Link

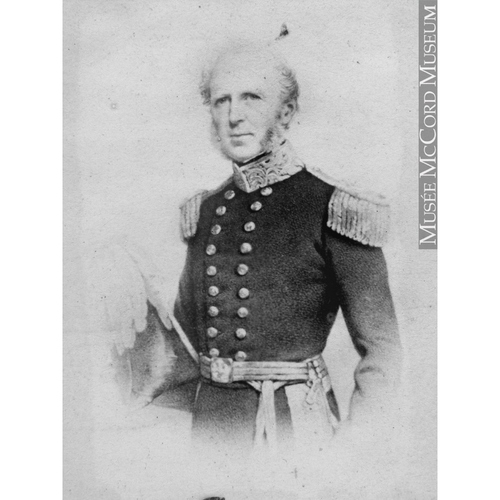

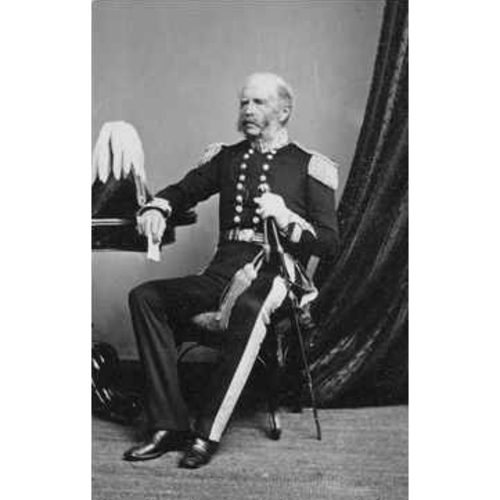

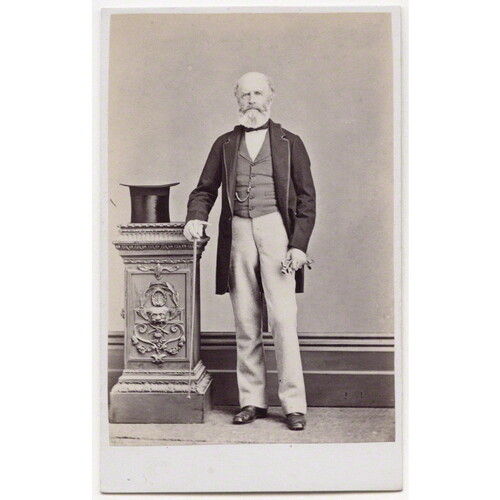

DALY, Sir DOMINICK, civil servant, politician, and colonial administrator; b. 11 Aug. 1798 at Ardfry, County Galway (Republic of Ireland), son of Dominick Daly and Joanna Harriet Burke, née Blake; d. 19 Feb. 1868 in South Australia.

The ancient Daly family of Galway into which Dominick was born had, through natural ability and judicious intermarriage, joined the governing class by the end of the 16th century, and attained nobility by the mid 19th. Dominick’s father, himself a commoner, had noble connections and his wife was the sister of Joseph Henry Blake, 1st Baron Wallscourt. Young Dominick, third son of this auspicious alliance, studied at the Roman Catholic St Mary’s College, Oscott, near Birmingham. After school, and an extended visit to an uncle who was a banker in Paris, he returned to Ireland, where his family arranged his appointment as private secretary to Sir Francis Nathaniel Burton*, lieutenant governor of Lower Canada. In 1823 Daly went with Burton to Canada, prompted by the Colonial Office’s warning that the Canadians would tolerate no more absentee office-holders.

In Lower Canada Daly worked hard and unobtrusively, while his employer so ingratiated himself with the French Canadians that in 1823 the assembly raised his salary and granted him a house rental allowance. Then, from 1824 until the autumn of 1825, Burton acted for Governor Dalhousie [Ramsay*] who was in England enlightening the Colonial Office about the problems of government in Canada. In an attempt to displace Dalhousie as governor, Burton endeavoured to undermine Dalhousie’s policies, and King George IV had personally to intervene on the governor’s behalf. In 1826, Daly returned with Burton to England, where Burton continued his campaign to ruin Dalhousie. Burton failed to have the governor ousted, but he did foist upon him young Daly who returned to Quebec in 1827 with instructions to Dalhousie to appoint him provincial secretary for Lower Canada.

Daly was to remit his £500 salary as provincial secretary to the former incumbent, absentee Thomas Amyot, retaining for himself the considerable fees accruing from the post. Amyot was a favourite in official London circles, and even in the new climate of opinion about absenteeism no minister whether Whig or Tory was willing to take any action more drastic than to suggest that the income be considered a pension rather than a salary. Daly was content to accept the arrangement, and was sworn to secrecy, as Lord Stanley explained, to prevent the assembly’s certain refusal to grant his salary should it become known that Amyot was to receive it. Dalhousie, who wanted to select his own provincial secretary, protested bitterly against Daly’s appointment. He charged that Daly was too young, irresponsible, and inexperienced for such an important position, but a Colonial Office re-evaluation vindicated Daly’s qualifications and he retained the post.

As provincial secretary Daly was in charge of preparing all official documents, including proclamations, as directed by the governor either alone or in conjunction with the Legislative Council, and in his care was the official government correspondence. Daly followed Burton’s example and ingratiated himself with his coreligionists, the French Canadians, by sympathizing with many of their grievances. His conscientiousness and impartiality in his work won respect and confidence, which made his post-rebellion transition from provincial secretary cum civil servant to provincial secretary cum politician so easy. Daly was also active in civic life, serving, for example, in 1836 on the administrative board of the new normal school in Quebec along with such notables as René-Édouard Caron*, mayor of Quebec, John Neilson*, and Hector-Simon Huot. Thus leading Canadians were exposed to his genial personality and old-fashioned gallantry which enhanced his hard-earned reputation for diligence, “integrity and usefulness.” Personally, Daly had followed his family’s model by marrying, on 20 May 1826, Caroline Maria Gore, third daughter of the influential Colonel Ralph Gore of Barrowmount, County Kilkenny, who was then on military service in Quebec.

At the time of the rebellions of 1837–38 Daly does not appear to have made any direct statement of his views, and this silence seems to have induced both sides to believe that he sympathized with them. After the rebellions Daly was one of the few high-ranking officials Lord Durham [Lambton*] retained in office, for such antagonists as Sir John Colborne and political leader Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine both recommended Daly in superlatives. In Durham’s administrative group, Daly was associated with such British radical Whigs as Edward Gibbon Wakefield, with whom he was to retain close and politically significant ties.

Durham designed a new colonial administrative system, and Lord Sydenham [Thomson*] was to implement it. Daly alone of the Lower Canadian office-holders survived the transition into the union of the provinces. Under the old system his office had been non-partisan, but under the new régime of 1841 it was regarded as one to be obtained by election. Sydenham therefore persuaded Daly to resign and find a seat in the assembly. Daly successfully contested the Eastern Townships constituency of Mégantic, and on 10 Feb. 1841 Sydenham appointed him provincial secretary for Canada East, and three days later a member of the Executive Council.

From 1841 until 1843 Conservatives and Reformers both found Daly an acceptable associate. Then and later he applied himself most diligently to his duties as provincial secretary, to which were added on 21 Dec. 1841 those of a member of the Board of Works. He gave these duties priority over routine parliamentary proceedings. He attended the assembly when possible but seldom participated, for though a charming conversationalist in private, he was not a good public speaker. In the council Daly believed it his duty to give freely of his long experience and to be as agreeable as possible. Thus his experience made him a valued member of Sydenham’s first administration. In the session of 1842 he was equally valued by his colleagues in the reconstructed Reform administration led by Robert Baldwin* and La Fontaine, who voluntarily retained him as provincial secretary. They considered him a colleague in good standing throughout the administration of Sir Charles Bagot*, and, for a while, that of Sir Charles Theophilus Metcalfe*. It took the ministerial crisis of 1843 to define clearly Daly’s political views.

Daly’s personal amiability, his sympathy for the French Catholics of Lower Canada, and his diligence had been taken by the Reformers as proof of political compatibility. In reality, Daly was a truly non-political man who believed that a combination of conscientious attendance to duty and loyalty to the sovereign was sufficient to determine his fitness to retain office. When his colleagues began quarrelling with Governor Metcalfe over such issues as ministerial accountability for all legislation and the right to patronage, Daly supported the governor simply because he was, as governor, her majesty’s representative in Canada. Soon Baldwin began to speak of forcing Metcalfe’s hand by resigning along with the other members of the council. Forty-two years of age, without an independent income, believing that his office was a permanent one contingent merely on the governor’s favour, Daly alone of Baldwin’s colleagues demurred. It had been a total misreading of his character to expect him to resign for political reasons; in supporting Metcalfe in 1843 he was consistent with his own principles if not with those of his colleagues.

A month before they resigned, Daly’s colleagues attempted to destroy his reputation by appointing a select committee to decide whether he should be impeached for having advised Lord Sydenham to appropriate the proceeds from the sale of marriage licences. The arrangement regarding Amyot was also exposed. The select committee completely exonerated Daly, but not before he had been publicly defended by Edward Gibbon Wakefield, his new political adviser and the self-styled confidant of the beleaguered Metcalfe. Wakefield disclosed the rift between Daly and his colleagues, which Baldwin denied as false and “grossly presumptuous,” though within a few weeks that rift was to become public knowledge.

On 27 Nov. 1843 La Fontaine and Baldwin announced their resignation. Then, accompanied by all their colleagues except one, they filed off the treasury benches; Daly alone remained. Two days later, after Baldwin had presented the case of those who had resigned to the assembly, Daly outlined the governor’s side of the issue: the governor refused to relinquish what he held to be prerogatives of the crown. Baldwin and his colleagues, on the other hand, stressed that their own accountability for the governor’s actions required him to accept either their advice or their resignations.

For about nine months the ministry consisted of Daly, William Henry Draper*, and Denis-Benjamin Viger. The accession of Viger and Draper to office bettered Daly’s unenviable position, but for the next several months the governor was unable to find anyone else to join his three councillors. Henceforth Daly had to face the hostility of Reformers, who believed he had betrayed them. On one occasion the irrepressible drunkard Thomas Cushing Aylwin* became so provoked in the assembly that he challenged the phlegmatic Daly to a duel. The duel on 26 March 1845, one of Canada’s last, was concluded without injury to either party, though shots were fired. Whenever possible, however, Daly maintained silence in the assembly. He preferred to concentrate on his official duties, which on 1 Jan. 1844 were expanded when he became provincial secretary for both sections of United Canada. By 2 Sept. 1844 three more appointments to the ministry had been made: Viger’s cousin Denis-Benjamin Papineau*, William Morris*, and James Smith. With these men as proof that he could manage without La Fontaine or Baldwin, Metcalfe called general elections, and the ministry was vindicated by a victory.

Daly himself was again returned for Mégantic. He continued to survive political upheavals, as well as the negotiations, in 1845 and 1847, between the Draper-Viger administration and various French Canadian Reform politicians, designed to achieve a ministry more responsive to the French Canadian majority from Lower Canada [see Draper; Caron]. The Reformers tried to make his exclusion a sine qua non of their entrance into a reconstructed council, but both times Daly’s colleagues refused to sacrifice him. Nonetheless, though Daly retained his seat in the general elections of 1847–48, the Reformers won a majority in the assembly, and on 10 March 1848 La Fontaine and Baldwin replaced him and his colleagues in the council. For the first time since 1822, the “perpetual Secretary” was out of work.

The new governor, Lord Elgin [Bruce], recognized Daly’s case as one of “great hardship”: “he resigned a permanent office on the introduction of Responsible Government, at the request of the Governor for the time being – by supporting Lord Metcalfe at the period of his rupture with his first council he rendered himself especially obnoxious to the Party who are now about to come into power. Deprived of office he has no means of subsistence .... No one in this Colony has in my opinion similar claims upon Her Majesty’s Govt.” Daly completely agreed, and hastened to seek reassurances from Elgin that he would be provided for. When they were forthcoming, he resigned his seat in parliament and returned to England, having first rejected Elgin’s offer of the administration of a Bahamian island. In England, however, Daly was persuaded by Wakefield to make excessive demands on Lord Henry George Grey at the Colonial Office, which led Grey to refuse him any government in the colonial service. Instead, Daly was named to a commission inquiring into the condition and claims of the New and Waltham forests. He held this position until the close of the commission in 1850–51. The following year, 1852, he was finally given a minor government, the lieutenant governorship of Tobago in the West Indies. There he accomplished nothing, for ill health forced him to leave after only six months.

In 1854 Daly was transferred to Prince Edward Island as lieutenant governor. He arrived on 12 June 1854 and received a warm welcome; for the next five years he proceeded to justify it by the firmness, moderation, and ability with which he administered the Island, self-governing for only three years. Almost immediately after Daly’s arrival, elections were held. The results were unfavourable to the Conservative government headed by John Myrie Holl which thereupon resigned, in compliance with the tenets of responsible government. The new Liberal government of George Coles* struggled on over the years with decreasing majorities, until the assembly had to be dissolved a few months after the elections of July 1858. Lieutenant Governor Daly respected the workings of responsible government, despite a tendency to advise and counsel more than was necessary, and he followed the example of his predecessor Sir Alexander Bannerman in opposing any attempts to exclude the executive from the legislative branches, such as were planned by the Tory government which came to power in 1859 just after Daly left the colony. The first Catholic governor of the Island, Daly was mistrusted by the Conservative party whose supporters came in large measure from the Protestant population; they often accused him of partiality towards the Liberals.

Legislation during the Daly administration included formalizing the provisions of the Reciprocity Treaty of 1854, the controversial acquisition of the large Worrell Estate by the government [see William Henry Pope*], the incorporation of Charlottetown and of the Bank of Prince Edward Island in 1855, and the establishment of a normal school, formally opened by Daly in 1856.

The most serious issue in the Island was the land question. In Durham’s words, when the Island was in the “very cradle of its existence,” it had been given up “to a handful of distant proprietors.” During Coles’ term of office the Liberals endeavoured to remove some of the abuses of the large landholdings. In 1855, after a number of unsuccessful attempts at ameliorative legislation, they passed a limited measure on behalf of certain tenants and squatters being ejected from their lands which would indemnify them for improvements they had made. Daly was undoubtedly torn between his liberal sympathies and his respect for the rights of property, and he was eventually pleased that he had only to inform the house that the Colonial Office had rejected the bill, thus preserving his popularity in the Island.

In 1858 Daly announced his resignation in the same speech in which he mentioned the rumours of a federal union of British North America. On 19 May 1859 he prorogued the assembly and delivered his farewell address, rejoicing at the harmony which had existed between the different branches of government throughout his tenure of office. There had been in fact harmony only between himself and the Liberals. In the same month Daly left the Island, hailed as one of its most popular administrators, and honoured by having been named a knight bachelor in 1856.

Back in England, Daly waited almost two years for another post. It came in October 1861, and it was to South Australia which had once figured so largely in Wakefield’s colonization schemes. Daly was to replace Sir Richard Graves MacDonnell* as governor and commander-in-chief, at a time when Australia was rough and turbulent, racist, and unsettled politically. In addition, his religion was an even more serious handicap than it had been in Prince Edward Island, where almost half of the population was Catholic. In Protestant South Australia his religion put him at a disadvantage faced by no other governor. Preceded and protected by no special reputation, he was at first attacked bitterly. Finally, in this country which had achieved responsible government only in 1855, where political parties were a thing of the future, and 40 years saw 41 governments formed on single issues, Daly’s personality and impartiality erased the suspicions felt on account of his Catholicism.

Daly died “in harness” on 19 Feb. 1868, from the debilitating anaemia which had for some months given him a noticeable pallor and taken away much of his energy. He left behind Lady Daly and five children, four of whom continued to live in South Australia. A fifth, Malachy Bowes Daly, later became lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia. At funeral services in Protestant churches across South Australia, the governor’s popularity, his “troops of friends,” his fairness and affability were eulogized and mourned.

Sir Dominick Daly was a colonial administrator of no special genius apart from luck and skill in finding influential sponsors and an ability to project an image of himself as a man of “high honor and integrity, of polished manners and courteous address – a good specimen of an Irish gentleman. . . . He was possessed of judgment and prudence, tact and discretion – in short, a man to be trusted.” His conscientiousness and impartiality earned him the praises of men of all political persuasions in Canada, until his indifference to politics, his lack of “political passion,” were so forcibly demonstrated in 1843. Only then did former friends and colleagues become bitter political enemies. Daly was an adherent of the old colonial system who tried to perpetuate that system in the Canadas long after it had been replaced by a new régime. Later, however, in Prince Edward Island and Australia, he respected the principles of responsible government, though he always gave priority to the rights of the crown and vested interests, priorities typical of a man of his aristocratic background. In all his colonial appointments he undertook to fulfil his duties creditably, and he served with distinction, if not with brilliance.

Debates of the Legislative Assembly of United Canada, I-IV. Elgin-Grey papers, I, 118–19, 148, 184, 298–99, 319. Examiner (Charlottetown), 18 Nov. 1861, 18 May 1868. Hincks, Reminiscences. Select documents in Australian history, 1851–1900, ed. C. M. H. Clark (Sydney, 1955). Dent, Canadian portrait gallery, III, 69, 71. Political appointments, 1841–65 (J.-O. Coté), 27, 41. [M.] E. [Abbott] Nish, “Double majority: concept, practice and negotiations, 1840–1848” (unpublished ma thesis, McGill University, Montreal, 1966), 87–97, 151–233, 234–82. L.-P. Audet, Le système scolaire, VI, 117, 251–52. Paul Bloomfield, Edward Gibbon Wakefield, builder of the British Commonwealth ([London, 1961]), 268–69. L. C. Callbeck, The cradle of confederation; a brief history of Prince Edward Island from its discovery to the present time (Fredericton, 1964), 168. Duncan Campbell, History of Prince Edward Island (Charlottetown, 1875), 112–15, 119, 121. Gertrude Carmichael, The history of the West Indian islands of Trinidad and Tobago, 1498–1900 (London, 1961), 311, 435. Leonard Cooper, Radical Jack; the life of John George Lambton, first Earl of Durham, etc. (London, 1959). Creighton, Macdonald, young politician. Davin, Irishman in Can., 168, 431. Dent, Last forty years, I, 86–87, 300, 323–24;11, 123–24. R. S. Longley, Sir Francis Hincks; a study of Canadian politics, railways, and finance in the nineteenth century (Toronto, 1943). MacKinnon, Government of P.E.I., 86, 97, 105–12. J. P. MacPherson, Life of the Right Hon. Sir John A. Macdonald (2v., St John’s, 1891), I. Douglas Pike, Australia: the quiet continent (Cambridge, Eng., 1962), 105–26. Racism or responsible government: the French Canadian dilemma of the 1840’s, trans. and ed. [M.] E. [Abbott] Nish (Toronto, 1967). Ernest Scott, A short history of Australia (6th ed., London, 1936), 209–84. Helen Taft Manning, The revolt of French Canada, 1800–1835: a chapter in the history of the British Commonwealth (Toronto, 1962), 140, 267. G. E. Wilson, The life of Robert Baldwin; a study in the struggle for responsible government (Toronto, 1933), 99, 101, 107.

Cite This Article

Elizabeth Gibbs, “DALY, Sir DOMINICK,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 2, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/daly_dominick_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/daly_dominick_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Elizabeth Gibbs |

| Title of Article: | DALY, Sir DOMINICK |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | April 2, 2025 |