Source: Link

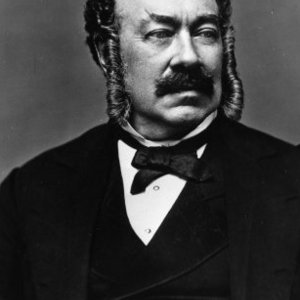

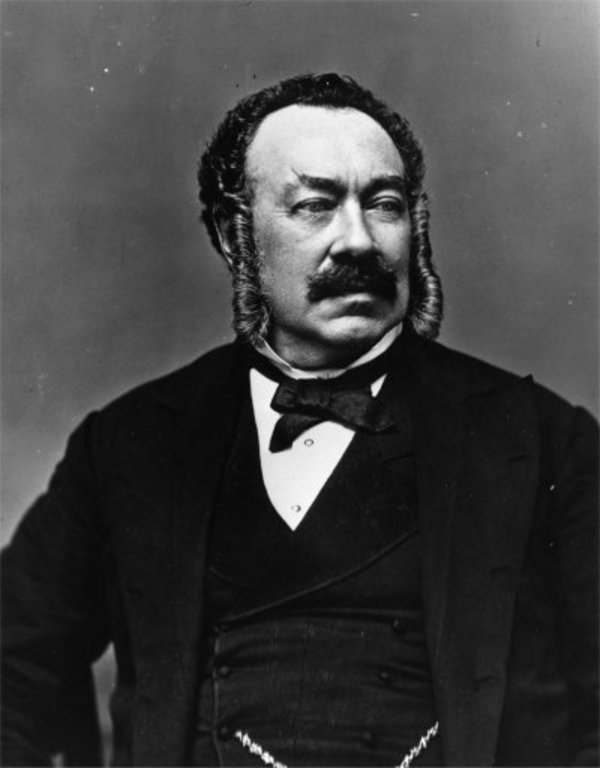

HENRY, WILLIAM ALEXANDER, lawyer, politician, and judge; b. 30 Dec. 1816 at Halifax, N.S., son of Robert Nesbit Henry, an Irish-born merchant, and Margaret Forrestall, née Hendricken; m. first in 1841 Sophia Caroline McDonald, who died in 1845, leaving an infant son; m. secondly in 1850 Christianna McDonald, and they had 7 children; d. 3 May 1888 at Ottawa, Ont.

William Alexander Henry’s father moved from Halifax to Antigonish, N.S., following the War of 1812 to operate a timber business and store. He was taught there by the Reverend Thomas Trotter*. During the late 1830s he studied law with Alexander McDougall, and he was admitted to the bar as attorney in 1840 and barrister in 1841. Henry was active in politics and in the 1840 election successfully opposed McDougall to gain election as the representative of Sydney (Antigonish) County in the assembly, thus entering the house at a time when the council of Lieutenant Governor Lord Falkland [Cary], led by James William Johnston* and Joseph Howe*, was making a strained attempt at coalition government. In the assembly Henry was described as an opportunist, a dull and prosy speaker who delivered a speech like “a tired boy turning a grindstone.” He was, however, personally popular, “a great mixer,” admired as a sportsman, and noted for looking after the interests of his constituents.

Henry was defeated in 1843, after the collapse of the coalition, but was re-elected in 1847 when he supported the Reformers’ call for responsible government. The Reformers had a margin of seven seats in the new assembly, and on 26 Jan. 1848 Henry seconded the non-confidence motion of James Boyle Uniacke* which forced Johnston’s resignation and the formation of the first responsible government under Uniacke and Howe. Re-elected in 1851, Henry became minister without portfolio in April 1852 at a time when prominent Liberals such as Thomas Killam* were criticizing the government for endorsing Howe’s scheme for a publicly financed railway from Halifax to Windsor, N.S. When in April 1854 William Young replaced Uniacke as leader of the Liberal government, he chose Henry to succeed Alexander McDougall as solicitor general.

In August 1856 Henry switched portfolios to become provincial secretary, but on 9 Feb. 1857 he resigned from the government, explaining that he could not accept his colleagues’ dismissal of William Condon from his position as gauger for the port of Halifax. Condon, a Roman Catholic and president of the Charitable Irish Society, had publicly disclosed Joseph Howe’s illegal campaign to recruit Americans for the British army in the Crimea: Condon had also taken part in a Halifax public meeting at which Howe and others thought disloyal statements had been made, and he had become involved in a newspaper controversy in which he went beyond the conduct suitable for a civil servant. The Condon–Howe affair took place during a period of bitter feeling in Nova Scotia between Roman Catholics and Protestants, and led to massive defections from the Liberal party by Catholics. Henry, a Presbyterian with Catholic relatives, represented a predominantly Catholic constituency and claimed in the assembly that Condon’s dismissal was persecution on religious grounds.

Ten days after Henry resigned from the cabinet, Young’s government was defeated in a Conservative non-confidence motion supported by all the Roman Catholic members and two Protestant Liberals, John Chipman Wade and Henry. His switch from Liberal to Conservative did not affect Henry’s popularity; he was re-elected in May 1859, a month after joining Johnston’s government as solicitor general. Although the Liberals gained a majority in the 1859 election, the Conservatives did not resign because Johnston and Henry maintained that some Liberals elected were legally disqualified from taking their seats. The British law officers did not agree, and on 7 Feb. 1860 the Johnston government yielded to the Liberals. When the Conservatives were returned to power in 1863 Henry again became solicitor general and on 11 May 1864 attorney general in the government of Charles Tupper*, who had succeeded Johnston as Conservative leader. Henry strongly supported Tupper’s free school legislation in 1864 and 1865 and opposed Isaac LeVesconte*’s efforts to have Roman Catholic separate schools established in law, believing with Tupper that Catholic representation on the Board of Public Instruction, as constituted by the cabinet, would protect Catholic interests.

There is no evidence that Henry was interested in the union of British North America before the Charlottetown conference in September 1864, which he attended as attorney general of Nova Scotia. Also a delegate to the Quebec conference the following month, he took an active part in its deliberations as well as in its social activities. He was a supporter of broad and unspecified federal powers and specific, limited fields of jurisdiction for the provincial legislatures, with a supreme court to decide questions of jurisdictional competence. He reiterated his belief that the people of Nova Scotia would benefit commercially from union, especially after his journey to Washington in 1866 as one of the British North American delegates who attempted unsuccessfully to persuade the Americans not to abrogate the Reciprocity Treaty of 1854. Henry also emphasized the necessity to unite for defence and to complete the Intercolonial Railway between Halifax and Quebec. His campaign in support of confederation was pursued in the face of the mounting opposition to the Quebec scheme nurtured by Howe and William Annand.

Henry was a delegate to the London conference in December 1866 at which the form of confederation was finalized, and was one of the attorneys general who helped frame the language of the British North America Act. Here may lie the source of the unproved tradition that he drafted the BNA Act. The Nova Scotia delegates in London voted to accept the Quebec Resolutions, but Henry objected to the limitation on the number of Senate seats, fearing that its members could thereby frustrate popular measures with impunity. He also supported Archbishop Thomas Louis Connolly*’s unsuccessful efforts to have the existence of Roman Catholic separate schools in Nova Scotia entrenched in the BNA Act; the separate schools of the religious minorities in Ontario and Quebec were guaranteed in the act. In the federal election of 18 Sept. 1867, when only one pro-confederate mp was elected in Nova Scotia, Henry was defeated in Antigonish County by Hugh McDonald, one of his former law students and a leading anti-confederate. After this loss, his first in 24 years, and another defeat in a federal by-election in Richmond in April 1869, Henry returned to the practice of law at which he was highly skilled. In 1870 he was elected mayor of Halifax and in 1873–74 president of the Charitable Irish Society.

Although nominally a Conservative, Henry felt more affinity for the federal Liberal party led by Alexander Mackenzie* than he did for the Liberal-Conservative party of Sir John A. Macdonald*. His estrangement from Macdonald, who had rewarded other pro-confederate leaders with appointments to the Senate or the bench, was coupled with the distance he maintained between himself and the anti-confederate government of William Annand in Nova Scotia. In 1873, when he was again defeated in a by-election in Antigonish, Henry switched his party allegiance from the Conservatives to the Liberals, ostensibly because of Conservative involvement in the Pacific Scandal, but in fact because he deeply resented the recent appointment of his rival Hugh McDonald as a county court judge. In October 1875, two years after the federal Liberals had come to power, the minister of justice, Edward Blake*, appointed Henry one of the judges of the newly created Supreme Court of Canada. It was felt that Henry, as one of the fathers of confederation, knew the intentions of the framers of the BNA Act, especially with respect to the division of powers between the federal and provincial legislatures.

In its first decade the Supreme Court, under Chief Justice William Buell Richards, was plagued by serious problems concerning its credibility and importance. Blake’s wish that appeals to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council should end was not politically acceptable to the Conservative party or to the British government, both of which wanted to maintain an imperial link by permitting such appeals. The Supreme Court was often bypassed when appeals were made directly from the courts of last resort in the provinces to the JCPC, and the Supreme Court’s decisions were frequently overturned by the English law lords. In parliament the court was subjected to many criticisms of its procedures. Henry diligently attended court, frequently dissented from the opinions of his fellow justices, and often had his judgements upheld by the JCPC. But Sir Robert Laird Borden* was to describe him as an “able” rather than a “great student,” and in 1880 fellow justices John Wellington Gwynne* and Samuel Henry Strong* complained to Sir John A. Macdonald that Henry’s judgements were “long, windy, incoherent masses of verbiage, interspersed with ungrammatical expressions, slang and the veriest legal platitudes inappropriately applied.” Henry continued to serve until his death in 1888, and contributed to the administrative reforms which led to greater respect and utility for the Supreme Court. His 13 years on the bench were, however, overshadowed by his more than 20 years of political activity in his native province; an obituary described him and Tupper as the men who had led Nova Scotia “by the nose into Confederation.”

AO, MU 159–62. PANS, MS file, William Alexander Henry, Commissions, 1854–75; Doc., 1848, 1851; MG 9, no.102; RG 1, 200: 3 April 1852, 4 April 1854, 14 Aug. 1856, 24 Feb. 1857, 15 April 1859; 201: 11 June 1863; 202: 11 May 1864; 262: ff.2, 7–21; RG 7, 36–37. Documents on the confederation of British North America: a compilation based on Sir Joseph Pope’s confederation documents supplemented by other official material, ed. G. P. Browne (Toronto and Montreal, 1969). N.S., House of Assembly, Debates and proc., 1855–61, 1864–67; Journal and proc., 1840–67. Casket (Antigonish, N.S.), 1857–58; 1864–65; 31 Oct. 1935; 9 Jan., 20 Feb. 1936. Morning Chronicle (Halifax), 5 Jan. 1876; 4, 7 May 1888; 16 Feb. 1900. Morning Herald (Halifax), 4, 7 May 1888. John Doull, Sketches of attorney generals of Nova Scotia, 1750–1926 (Halifax, 1964), 70–74. The courts and the Canadian constitution: a selection of essays, ed. W. R. Lederman (Toronto, 1964). Leading constitutional decisions; cases on the British North America Act, ed. P. H. Russell (Toronto, 1965). G. [G.] Patterson, Studies in Nova Scotian history (Halifax, 1940); More studies in Nova Scotian history (Halifax, 1941). D. G. Whidden, The history of the town of Antigonish (Wolfville, N.S., 1934), 89–90, 102–5. P. R. Blakeley, “William Alexander Henry, a father of confederation from Nova Scotia,” N.S. Hist. Soc., Coll., 36 (1968): 96–140. J. B. Brebner, “Joseph Howe and the Crimean War enlistment controversy between Great Britain and the United States,” CHR, 11 (1930), 300–27.

Cite This Article

Phyllis R. Blakeley, “HENRY, WILLIAM ALEXANDER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 1, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/henry_william_alexander_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/henry_william_alexander_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Phyllis R. Blakeley |

| Title of Article: | HENRY, WILLIAM ALEXANDER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | April 1, 2025 |