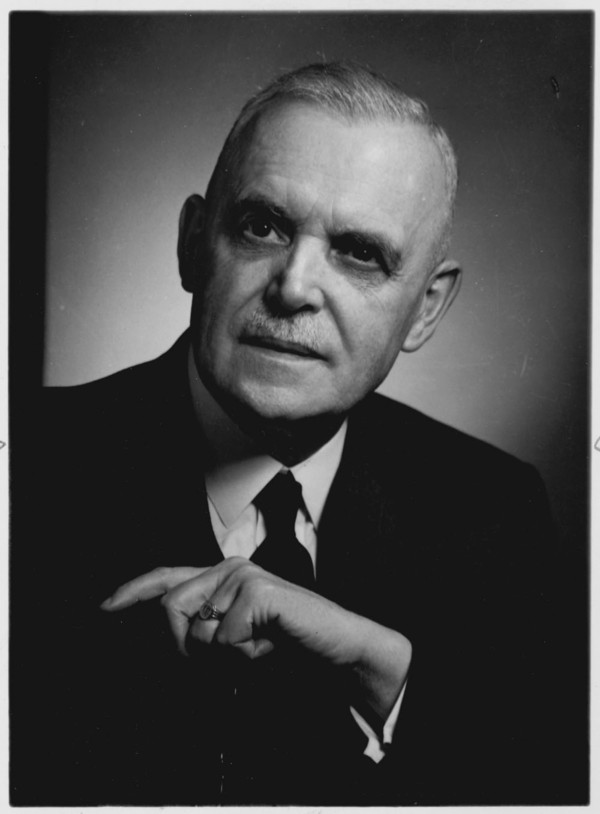

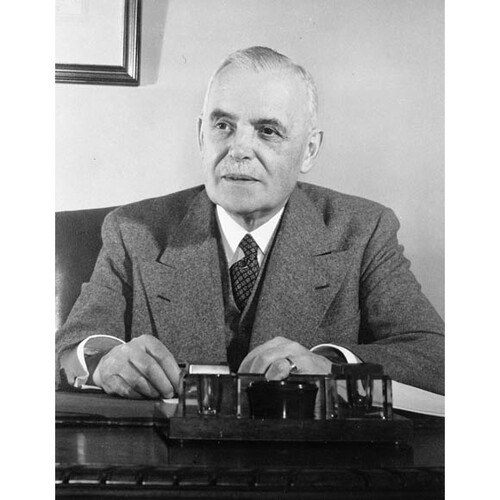

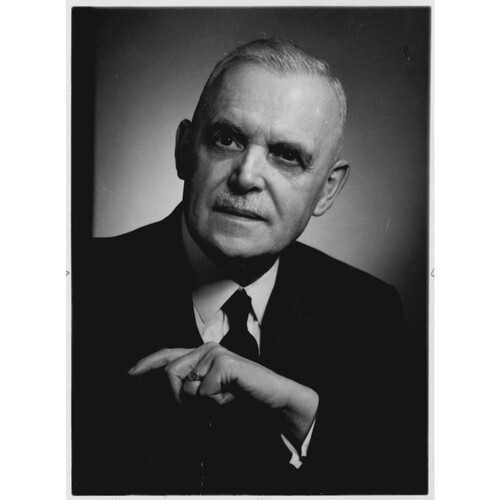

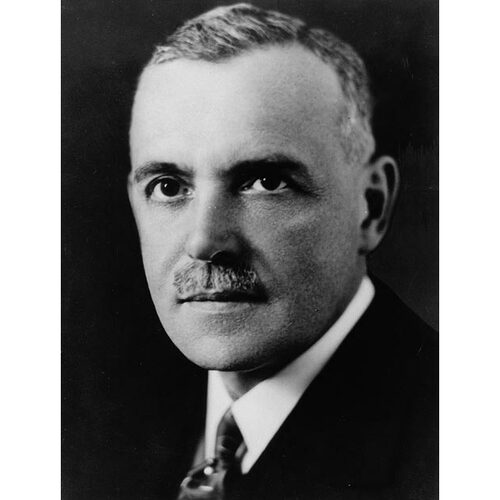

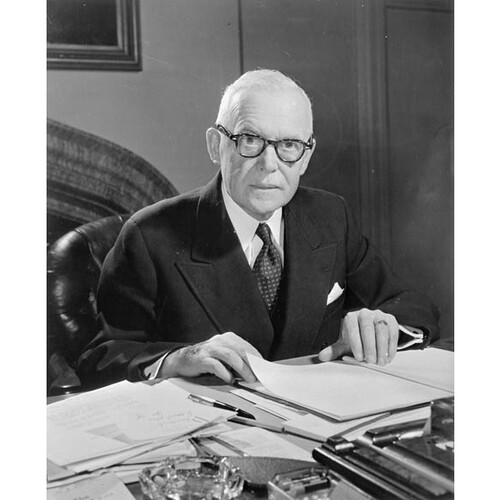

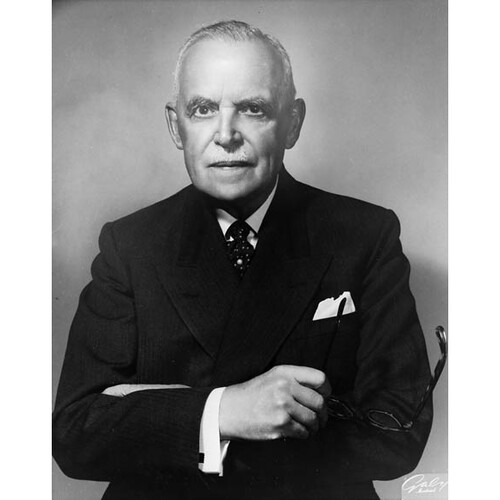

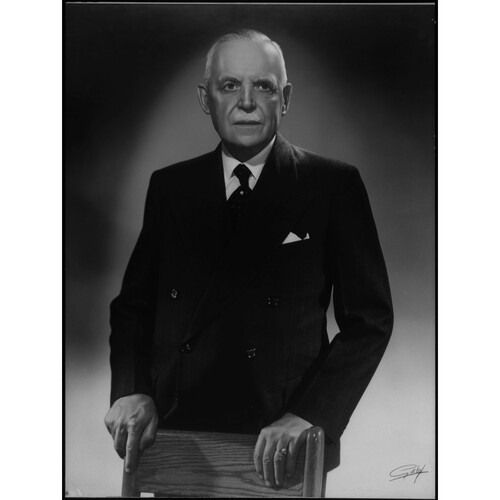

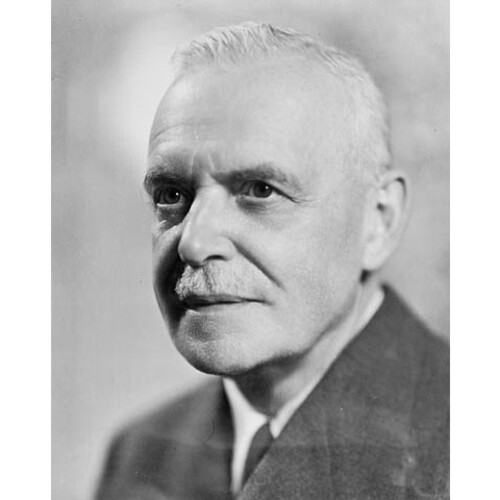

ST-LAURENT, LOUIS-STEPHEN (baptized Louis-Étienne), lawyer, professor, and politician; b. 1 Feb. 1882 in Compton, Que., son of Jean-Baptiste-Moïse St-Laurent and Mary Anne Broderick; m. 19 May 1908 Jeanne Renault in Beauceville, Que., and they had two sons and three daughters; d. 25 July 1973 at Quebec, and was buried in Compton.

Nicolas Huot Saint-Laurent had arrived in New France around 1660. Starting in the Quebec City region, the family gradually moved west along the St Lawrence River, settling in Nicolet in the early 19th century. Though Huot Saint-Laurent was a man of some learning - he served as a sheriff at Quebec - most of his descendants were illiterate farmers. Jean-Baptiste-Moïse St-Laurent, the first family member in 150 years to attend school, abandoned farming for commerce. He moved with his father from Trois-Rivières to Sherbrooke in the Eastern Townships to set up shop and then to the nearby village of Compton, where he opened a general store and married the local schoolteacher, Mary Anne Broderick, the child of Irish immigrants. Jean-Baptiste learned English because she refused to speak French. The Brodericks and the St-Laurents were Roman Catholics. Mary Anne, for her part, had some passing acquaintance with Protestants, having been raised for a time in her childhood in a Protestant family. Louis-Stephen St-Laurent was the first of their seven children.

At the time of his birth, Compton was mainly English speaking. It and the surrounding township of Compton would become majority French at some point between 1901 and 1911. The St-Laurents’ home, next to their store, served as a social centre for the village. In a political riding long dominated federally by the Conservative John Henry Pope*, Jean-Baptiste was a faithful Liberal and would run in a provincial by-election in 1894. The couple’s children spoke French with their father, but because of their mother they were equally at home in English. Educated in French in the local separate school, Louis had learned to read and write English first, he was exposed throughout his childhood to English literature, and he spoke the tongue with no accent. He was a talented and studious child, and his family were encouraged to seek further education for him. He left Compton in 1896 to enter the Séminaire Saint-Charles-Borromée in Sherbrooke. Attendance was an expensive proposition for the son of a country storekeeper, but Louis was buoyed by Compton’s abbé, Joseph-Eugène-Édouard Choquette, who had persuaded the college authorities to waive the customary tuition fees. At the seminary, which was a bilingual institution, its staff a mixture of French and Irish priests, St-Laurent distinguished himself; he developed a writing style in both French and English and played an active role in student life. Although his parents hoped he would become a priest, he opted instead for law on graduation in 1902.

Financial and cultural considerations led him to the Université Laval at Quebec rather than McGill University in Montreal. At Laval’s law school, the Liberal St-Laurent studied under some of the city’s most prominent Conservative lawyers, who made up much of the faculty. Despite taking time out to assist his father in another unsuccessful run for the provincial legislature, in 1904, St-Laurent graduated at the top of his class in 1905 and won the Governor General’s Medal. He was also offered Laval’s first Rhodes scholarship, but refused it in order to turn to a (presumably lucrative) legal career. It started modestly. St-Laurent accepted a berth in the office of a prominent Quebec City lawyer, Louis-Philippe Pelletier*, at $50 a month. He found time as well to court Jeanne Renault, the daughter of a prosperous merchant in Beauceville; they had met at a party in Quebec in 1906 and married two years later. She was accustomed to a comfortable life, and the marriage forced St-Laurent’s departure from Pelletier’s firm and his meagre salary there. Instead, at the beginning of 1909, he formed a partnership with Antonin Galipeault, a young lawyer with political - reliably Liberal - prospects. Galipeault found St-Laurent’s easy English a distinct advantage. Equally important, St-Laurent was a notoriously hard worker, with a reputation for painstaking preparation. When Galipeault was elected to the legislature in February 1909, St-Laurent took over much of the firm’s ordinary business; eventually he found himself specializing in commercial law. The firm expanded - the partners soon included Liberal senator Philippe-Auguste Choquette* - and in 1914 they moved to impressive quarters in the Imperial Bank Building on Rue Saint-Pierre. The same year St-Laurent joined his mentor, L.-P. ;Pelletier, as a professor of law at Laval. In 1915 he was made a provincial kc and received an honorary lld from Laval. By this time he was earning $10,000 a year; though comfortable, he would never be rich.

The St-Laurent family grew steadily, numbering five children by 1917. In 1913 he had built a 15-room house on the Grande Allée, Quebec City’s most fashionable street. This house, servants, and an automobile (acquired in 1916) were easily within his means, which depended on his reputation for steady, reliable intelligence in his practice. By the 1920s his work extended to cases before the Supreme Court of Canada. St-Laurent, according to a contemporary at the Quebec bar, Warwick Fielding Chipman, “was solid, sound, pleasing to his courts, and established an intimacy with them. He had a human touch despite his technical detail and thoroughness.”

St-Laurent’s interests diverged from those of Galipeault, whose political career took more and more of his attention. They went their separate ways, amicably, in 1923. By this time St-Laurent was being frequently retained by the governments of both Canada and Quebec, sometimes on constitutional cases. In an important test case before the Supreme Court in 1926, he argued for minority rights: the Jewish demand for representation on Montreal’s Protestant Board of School Commissioners or for a separate Jewish system of schools. In the event, representation was refused but provincial authority to establish separate schools for non-Christians was recognized. It cannot be said that St-Laurent consistently took a provincial or a federal position in his cases, nor was he always successful. He was, however, successful enough to join the select and highly remunerated elite who pleaded before Canada’s highest court of appeals, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London, England. As biographer Dale Cairns Thomson has observed, St-Laurent’s quiet, scholarly arguments matched the style of the British law lords. In 1928 the JCPC, which rarely gave compliments, praised his illuminating and able argument on behalf of Ottawa in a conflict between the Quebec Civil Code and the federal Bankruptcy Act.

St-Laurent, though known as a Liberal supporter, was not much involved in partisan activity in the 1910s and 1920s. His one appearance on a platform, in support of Charles Gavan Power* in Quebec South in 1926, was unremarkable. He was not indifferent, however, to the larger political currents swirling around him, and his national reputation and interest in national affairs grew apace. During World War I he had been a prominent participant in the Bonne Entente movement that sought to reconcile the divergent perspectives of English and French Canadians, strained by the conscription issue and the bilingual schools question in Ontario. Within legal circles, he served as bâtonnier of the Quebec bar in 1929 and as president of the Canadian Bar Association in 1930-32. St-Laurent became a well-known speaker in English Canada, especially on the theme of national unity, and in opposition to such French Canadian nationalists as Abbé Lionel Groulx* who blamed others - the English and the Jews - for the inequities of the Quebec economy and the perceived subordination of French Canadians in society.

The Great Depression of the 1930s severely tried Canada’s political and economic institutions. Some provinces struggled financially; only the federal government appeared to have the resources to deal with the burden of welfare and reconstruction. In 1935 the Conservatives under Richard Bedford Bennett* passed New Deal legislation that included employment and social insurance and regulations governing minimum wages and hours of labour, fields that many legal authorities felt were provincial responsibilities. In January 1936 the new Liberal government of William Lyon Mackenzie King* submitted this legislation to the JCPC for its opinion and hired St-Laurent as counsel. He founded his argument on section 132 of the British North America Act, which gave the federal government authority to implement imperial treaties, in this case the labour aspects of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. It was at best a difficult proposition, and to no one’s great surprise St-Laurent lost on the main issues, the labour conventions and the Employment and Social Insurance Act.

The crisis, economic and constitutional, endured and King’s next expedient, in 1937, was to appoint a royal commission on dominion-provincial relations chaired by Ontario’s chief justice, Newton Wesley Rowell*. James McGregor Stewart* of Halifax and St-Laurent were named commission counsel. No end of a lesson, the experience exposed St-Laurent for the first time to a Canadian reality outside the business centres of the east. It corrected his impression, based on magazine stories, that western wheat farmers enjoyed winter vacations in California and were a source of unlimited revenue. The depression-bound west, in fact, was a sink-hole of misery, with no markets for its products and no means to support its people. St-Laurent saw a need for stronger federal authority. “It seems likely that our constitution will have to be amended if Confederation is to survive,” he told a French-speaking audience in Winnipeg in January 1938. Events soon overtook the royal commission. Before it could report under its new chairman, Joseph Sirois* (Rowell having resigned due to illness), World War II broke out. In 1940 it did recommend constitutional adjustments, mainly in the direction of greater federal activity in the field of social security, but by this time Ottawa had already assumed the power to direct the war effort, subordinating provincial authority to this greater cause.

King and his Quebec lieutenant, justice minister Ernest Lapointe*, tried to appease opinion in Quebec on the volatile issue of conscription. Their promise of no conscription, first made in the spring of 1939, was repeated in the provincial election of October and again in the federal contest of March 1940. The Quebec ministers in King’s cabinet, led by Lapointe, pledged to resign if conscription was imposed, but, like everyone else, King and Lapointe underestimated the problems the war would bring. When Germany defeated France in June, Britain and its empire, including Canada, were left to fight on alone. Fearing the worst, King and Lapointe agreed to impose conscription after all, but only for home defence. Canadians sent overseas would be volunteers. When Lapointe died in November 1941, a large gap opened in the prime minister’s carefully balanced political structure. King consulted several Quebec notables, including those in his cabinet as well as Archbishop Jean-Marie-Rodrigue Cardinal Villeneuve*. King’s first thought was to recruit Liberal premier Adélard Godbout*, but he did not wish to be translated to Ottawa. It was on the suggestion of Villeneuve and Pierre-Joseph-Arthur Cardin*, the minister of transport, that King began to consider St-Laurent, who earlier that year had co-chaired the Victory Loans committee in Quebec. He knew him “only as a distant and rather chilly lawyer,” while St-Laurent knew King hardly at all.

On 4 December, King telephoned St-Laurent, asking him to be in Ottawa the next day. Though he did not give a reason, it was obvious. After lunch on the 5th, he proposed that St-Laurent succeed Lapointe as minister of justice and mp for Quebec East. Anticipating that St-Laurent might be reluctant to leave his home, and an income in excess of $50,000 a year, for the relatively ill-paid and insecure life of a minister and politician, King appealed to his sense of duty. The war was a national crisis, and Canada (and King) needed somebody who could “interpret the Quebec point of view” to the rest of the country. St-Laurent asked for time to consult; the answers were mixed from his family but affirmative from most of his friends, the cardinal, and the premier. On 10 December he was back in Ottawa, to be sworn in as minister of justice. Soon after, the Liberals of Quebec East adopted him as their candidate in a by-election set for 9 Feb. 1942.

St-Laurent entered the cabinet just as the war expanded to include the United States, a fact that put pressure on King to implement a policy of total war, which would include a commitment to conscription not just for home defence but also for overseas. The problem was the government’s promise of 1939-40. The prime minister and his cabinet worried over this question through Christmas, and in January 1942 they agreed on a possible solution. There would be a plebiscite, in April, to ask voters to release the government from its pledge. St-Laurent was cooperative; he had made no promise and would not be bound by commitments made by others. He took this line in the by-election, running against a nationalist candidate, and won. The plebiscite was another matter. Outside Quebec, the electorate went along with King’s purpose. Inside Quebec, voters opted against the government by a heavy margin. In the aftermath, in May, as King prepared to push through parliament a bill (Bill 80) that would repeal the legislative provision against conscription, Arthur Cardin quit the cabinet.

Cardin’s departure confirmed St-Laurent’s position as the senior Quebec minister. He had already succeeded Lapointe on cabinet’s War Committee, becoming Quebec’s voice in the higher direction of the conflict. St-Laurent spoke effectively on behalf of the government’s conscription policy in the House of Commons on 16 June, arguing against the contention of Quebec nationalists that Canada was at war merely in the service of the British empire. The dominion was engaged in its own interests, not those of Britain, and he urged English Canadians to accept French Canadians “as full partners and full citizens.” King warmly shook St-Laurent’s hand on the conclusion of the speech, and he recorded in his diary that the occasion was of great symbolic significance. With passage of Bill 80 in July, the conscription issue was defused. Conscription for overseas service was now legally possible, but it need not be implemented until the military ran short of men. With the Canadian army in England in anticipation of an eventual invasion of the European mainland, that day was not at hand. King and his colleagues fervently hoped it would never come.

In Ottawa, St-Laurent was now accepted as King’s Quebec lieutenant. He gave frequent speeches there on the war effort and national unity; in addresses that October he foresaw the need for policies on social security and to consolidate the levels of employment security made possible by the war. In Quebec the church was divided on his support for social welfare. Right-wing clergy opposed it, but he was indifferent to their arguments. From time to time, as a senior minister, St-Laurent assisted King directly, including a spell as acting minister of external affairs (a post traditionally held by the prime minister) during King’s visit to London in the spring of 1944. The same year St-Laurent attended the conference at Bretton Woods, N.H., that led to the creation of the International Monetary Fund, and in April-May 1945 he participated with King in the founding conference of the United Nations in San Francisco. His presence meant that Quebec’s interests were represented, but St-Laurent also viewed these occasions as an affirmation of the larger national interest apart from regional or linguistic considerations. During these two years he also carried out his duties as minister of justice, including the appointment of judges and advice to his colleagues on the constitutionality of proposed legislation.

St-Laurent took a broad view of the federal spending power, which he held could justify such programs as family allowances; the legislation for family allowances emanated from his department in 1944. In March 1945 he supported a sweeping program of economic reconstruction and more social welfare, including federal-provincial cost-sharing schemes for old-age pensions and hospital and medical insurance, and the federal assumption of responsibility for the unemployed. He brushed aside warnings that these proposals would “precipitate acrimonious disputes with the provinces,” though it was over revenue-sharing differences that the program would run aground. Disagreement should not deter his colleagues from supporting good policy, the minister of justice argued. “Acrimonious dispute was inevitable with Quebec in any case,” and he did not believe the people would automatically support the provinces over Ottawa. Canadians identified with provincial programs, he reasoned, because they “were constantly made aware of the services which provincial governments render while they tended to think of the central government as one imposing burdens such as taxation and conscription.” Sound federal initiatives, including family allowances, would correct and even reverse this situation.

The principal issue confronting the government in 1944-45, however, was conscription, not social welfare. Heavy casualties suffered during the Normandy Invasion of 6 June 1944 and afterwards caused the military’s pool of manpower to run dry. The minister of national defence, James Layton Ralston*, told the prime minister in October that conscript reinforcements must be sent immediately. King manoeuvred to secure the backing of colleagues who were, he knew, deeply divided on the issue. At each stage, he turned to St-Laurent, keeping him apprised and firming up his support. Content with the policy adopted in July 1942, St-Laurent saw no need for conscription with the war’s end in sight and other means for securing reinforcements untried. Still, he watched King’s policy sympathetically. Realizing that the prime minister had done everything in his power to avoid offending Quebec, the justice minister moved from a position on 30 October where he “could not possibly support introduction of conscription” to resigned acceptance a month later. St-Laurent’s attitude was crucial to King: no other Quebec minister had as much prestige or authority. In the end, conscripts reached Europe in early 1945.

The government survived the conscription crisis but its political future was most uncertain. An election was due in 1945, and King’s Liberals were beset by an assortment of Quebec nationalists, Ontario conscriptionists, and prairie socialists. As much as anything, fortune favoured the Liberals. The European phase of the war came to an end in May 1945, a month before the election. King and St-Laurent marked the occasion with radio broadcasts in English and French; the choice of St-Laurent as oratorical partner underlined his primacy among the Quebec ministers. The Liberals won the election, though narrowly. “Independent Liberals” elected in Quebec could cause trouble in the future by tending towards Quebec nationalism and the provincialist policies of Union Nationale premier Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis*. The election was, in a sense, King’s last hurrah. Aged 70, he understood it was time to give thought to a successor.

Fortunately, there was one at hand, though St-Laurent’s decision to run in the election had been a surprise to many. Perhaps it was based on the timing of the campaign, before the war was truly finished; perhaps he sensed that national unity, a fragile flower, demanded his continuing attention. There were problems of policy as well, not least dominion-provincial relations, which the war left unresolved. In the summer of 1945 St-Laurent participated, along with the minister of finance, James Lorimer Ilsley*, and the minister of reconstruction, Clarence Decatur Howe*, in a dominion-provincial conference on reconstruction. The federal government proposed nothing less than a redistribution of responsibilities, with Ottawa taking the lead in the comprehensive social welfare scheme that St-Laurent had supported the previous spring. Duplessis and Ontario premier George Alexander Drew objected, and their objections prevailed. Duplessis presented the episode as an ambitious power grab by Ottawa, but he could not present it in strictly ethnic terms because of St-Laurent’s prominent presence in the federal delegation.

The King government had an ambitious external agenda as well, and here too St-Laurent’s role was crucial. The government believed that trade should to be restored to pre-war levels. A surplus in trade with Britain had usually helped to pay for a trade deficit with the United States, but the war had devastated British commerce and it would take time for exports to recover. To help the British return to their role as purchasers of Canadian wheat, apples, and cheese, Canada proposed a loan of $1.25 billion (roughly a tenth of Canada’s annual gross national product) spread over a number of years. The advance was to be made in conjunction with an American loan of $3.75 billion, the terms of which set the pattern for the Canadian loan. To Quebec nationalists it was more evidence of Canada’s objectionable subordination to the empire. It was essential, then, to the political credibility of the government’s case that St-Laurent accept the desirability, even the necessity, of the loan. Persuading him that it was in Canada’s interest, not just Britain’s, was a tall hurdle for government economists to surmount, but once convinced, St-Laurent took the lead in defending the loan in parliament in April 1946 and in Quebec against the vitriolic abuse heaped on him by the nationalists, some of them nominal Liberals.

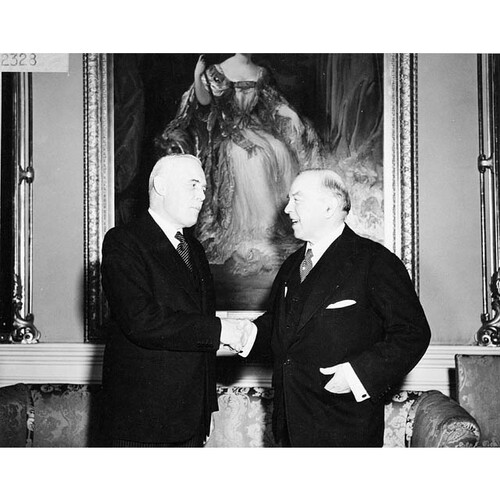

St-Laurent’s career now stood at a turning point. When King returned exhausted from a trip to Europe in August, St-Laurent, as acting prime minister, met him in Montreal. King used the occasion to raise the question of succession. St-Laurent was the logical leader and future prime minister, and King asked him to accept the possibility. He hesitated. Life as a minister had drained his savings. His law practice had suffered, and his sons, though qualified as lawyers, were too inexperienced to take his place. Eventually, however, he accepted King’s proposition, and with it an immediate change in assignment. King broke with tradition and separated the office of secretary of state for external affairs from that of prime minister. St-Laurent thus became minister of external affairs on 4 Sept. 1946 as part of a major cabinet shuffle. He did not see the appointment as definitive. There was still a chance for him to return to private life, or so he assured his colleagues, but these same colleagues, especially Howe, were beginning to think of him for the longer term; it was clear that King’s departure could be postponed no further. On the same day King made another important commitment: he appointed a new under-secretary for external affairs, Lester Bowles Pearson, the former Canadian ambassador in Washington. It was the beginning of a long and advantageous collaboration.

St-Laurent was aware that the international scene was not promising. The Soviet Union, the world centre of communism, was expanding its influence in eastern Europe, already occupied by the Red Army. Soviet policy alarmed the British in particular and they passed their fears on to King during his several visits to London. He hardly needed to be reminded: a Soviet spy ring had been uncovered in Ottawa in September 1945, when a defector, Igor Sergeievich Gouzenko, arrived unexpectedly at St-Laurent’s office. As minister of justice, he followed the subsequent police investigation and the revelations of a royal commission on espionage. He did not need to be told the Soviet Union represented a clash of ideologies that transcended national boundaries. Yet foreign affairs were never an easy issue in Canada because of what were thought to be differing opinions on the subject between English and French Canadians - the latter were assumed to be disengaged and isolationist - and to have them re-emerge as a major question only a year after the war posed a challenge to the King government. Certainly King bore this risk in mind when he appointed a French Canadian to the portfolio.

The Department of External Affairs drew from the Canadian academic elite. Most of its officers were educated abroad, and the department tried to recruit French as well as English Canadians. It might be thought that St-Laurent, who had travelled little until well on into middle age, and the sophisticated members of the foreign service were ill-matched, but that did not prove to be the case. The diplomatic staff appreciated his logical and quick habits of thought and his powers of concentration. They appreciated him even more because they had endured King’s fussiness. St-Laurent was the opposite: courteous and easy to brief, he relied on them to present him with clear recommendations that he would consider on the spot, and then accept or reject. Unlike King, he was accessible and attended his office regularly. Best of all, as senior diplomat Escott Meredith Reid* explained, St-Laurent backed up his staff when they were in difficulty. “I knew,” Reid wrote, “that here was a man who deserved loyalty because he was loyal.” In a cabinet of strong ministers, St-Laurent distinguished himself by his unusual executive capacity.

The two most important items on St-Laurent’s plate were the confrontation with the Soviet Union - what was coming to be called the Cold War - and a proposal for union with the British colony of Newfoundland. On the Cold War, there was little to be done: its development was beyond Canada’s control and in any case Canadians had no hesitation in taking the side of the West. It would have been impossible to do anything else. On Newfoundland, however, there was a choice. It had remained out of confederation in 1867 [see Sir Ambrose Shea*], and had resisted the notion ever since. But the Island’s history as an autonomous jurisdiction had been rocky, and by 1946 some Newfoundlanders, notably Joseph Roberts Smallwood*, were prepared to reconsider union. St-Laurent found the idea of completing confederation highly attractive, and early on he became Newfoundland’s strongest supporter in the King cabinet. He ignored objections from the Quebec government, which had territorial claims against Newfoundland and demanded a right of veto over the admission of any new province. Once again St-Laurent advanced a strong defence of national power, holding that the federal government represented all Canadians. He headed negotiations with Newfoundland in the summer of 1947 and again in the fall of 1948. The discussions bore fruit: on 31 March 1949 it would join Canada, with St-Laurent presiding over the ceremonies in Ottawa as prime minister.

St-Laurent’s main duties in 1947 lay outside the country, in explaining the world to Canadians and Canada to the world. Much of his work had been done. The experience of the war, and reflection on the slide to war in the 1930s, had convinced many that their country could take no refuge in isolation or comfort from its geography. St-Laurent searched for an occasion to define Canada’s foreign policy. He took advantage of an invitation to inaugurate a lecture series at the University of Toronto in January 1947 (the first Gray Lecture) to give what was probably his most notable speech. It was drafted by one of his officers, Robert Gerald Riddell, a former teacher at the university who was familiar with what a Toronto audience would expect. But there was no doubt that St-Laurent was entirely comfortable with the ideas in the speech, which served to define the bases of Canadian foreign policy for the next generation. Not surprisingly, he placed national unity first among the principles that must underlie this policy. A disunited Canada would be powerless, he reminded his audience. The search for national unity did not mean that Canadians should avoid the subject of foreign policy as too dangerous or contentious. They agreed on other principles - political liberty, Christian values, and “the acceptance of international responsibility” - and these principles, he argued, justified an active role in international affairs. He prescribed engagement with Britain, the United States, and France, as well as commitment to “every international organization which contributes to the economic and political stability of the world.” Seen from St-Laurent’s perspective, foreign policy should unite rather than divide Canadians.

In 1947 and later St-Laurent repeatedly stressed the ideological gulf between Canada (and the West in general) and totalitarian communism. Like other ministers and most of his diplomatic staff, he did not believe the Soviet Union was out to provoke war, but he did agree that economic and social disorder abroad favoured its cause. Political uncertainty more than anything else was undermining the democracies of western Europe. St-Laurent saw a need for greater international security, and he agreed too that the UN was failing to provide it. In speeches and in the cabinet he promoted the idea of a Western or Atlantic security organization that would supplement the UN. He did not participate directly in the negotiations in Washington that would produce the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in 1949, but he was recognized as one of the first responsible politicians to propose such an institution.

Canada’s response to another focal point of clashing ideologies, Korea, was complicated by King’s lingering interest in the conduct of his old department. In December 1947 St-Laurent supported American attempts within the UN to establish a stable regime in South Korea through elections, and he recommended to the cabinet the appointment of a Canadian to a UN committee to study the subject. The appointment had actually been approved by J. L. Ilsley, now the minister of justice, who was interim head of the Canadian delegation at the UN in New York City at the time, but St-Laurent and his staff saw no reason to object. This minor event triggered an entirely disproportionate reaction from the prime minister, who dreaded the possibility that UN involvement in a difficult international situation might set off a third world war. King demanded that St-Laurent rescind the appointment. St-Laurent, who believed he would be abandoning his staff and another minister, refused. Only when King understood that his chosen successor, and half his cabinet, might resign did he withdraw his demand. The incident “marked a watershed in the political lives of King and St. Laurent,” in the estimate of journalist William Bruce Hutchison*.

It was clearly time for King to go, but he had one more function to perform - assuring that St-Laurent would in fact be his successor. King scheduled a Liberal convention for 7 Aug. 1948. St-Laurent was nominated, and so were three others: C. G. Power, agriculture minister James Garfield Gardiner*, and national health and welfare minister Paul Joseph James Martin*. To illustrate the trivial nature of the opposition, King had had the names of half his cabinet placed in nomination, and each named minister then duly withdrew, telling the convention that a better man - St-Laurent - was providentially available. In the background C. D. Howe managed such organization as was needed for St-Laurent. Martin also withdrew, and Power and Gardiner were overwhelmingly beaten. St-Laurent had to wait some months for the prime ministership; on 15 November, King finally resigned and handed over office. St-Laurent had occupied the intervening time as justice minister, making room for Pearson to become secretary of state for external affairs.

St-Laurent was already a known quantity around the country, and his cabinet was almost the same as King’s. As prime minister, however, he was very different, though it was a difference best understood in Ottawa. St-Laurent ran the cabinet in his own way. Under him, each minister had his individual responsibility, and he did not intrude unless a subject slopped over departmental boundaries or higher political direction was plainly needed. He shared, however, King’s aversion to foreign travel, believing that the prime minister could ill afford time outside the country. Most trips were left to Pearson or to Martin, often as a delegate to the UN. St-Laurent spent most of his time in Ottawa or at his vacation home, bought in 1950, on the shores of the St Lawrence in Saint-Patrice, Que. He did grudgingly consent to the purchase in 1951 of an official prime-ministerial residence at 24 Sussex Drive in Ottawa, though he insisted on paying rent. It was then that Jeanne St-Laurent moved to Ottawa from their home in Quebec City. As a prime minister’s wife, she was not a major figure. She would go on tour with her husband, but she refused to fly and, according to his biographer, never became reconciled to living in Ottawa.

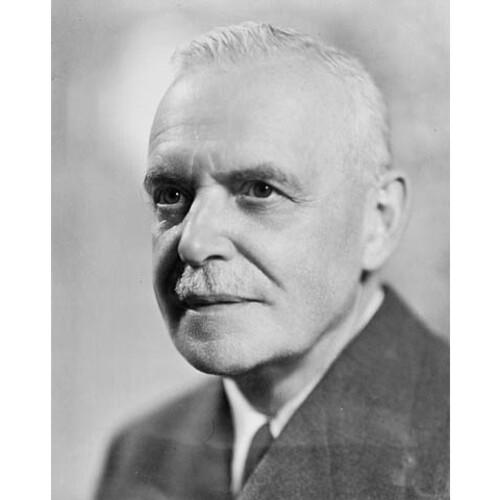

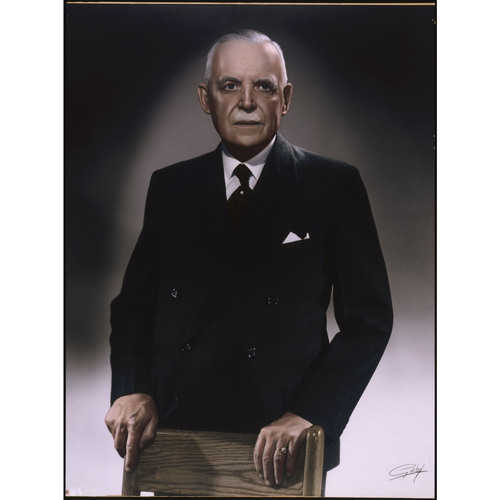

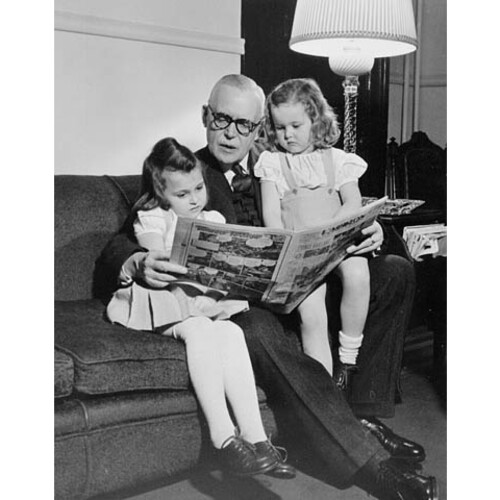

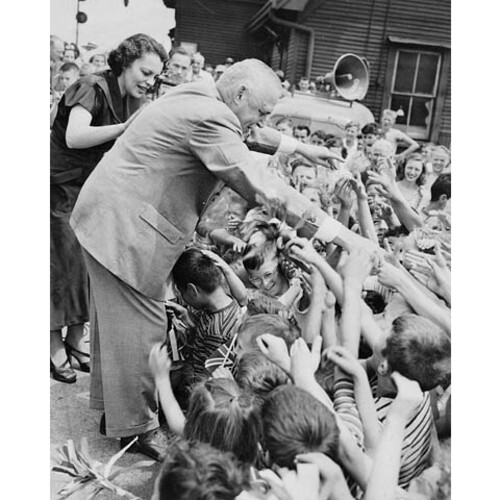

One duty did involve travel. As party leader, St-Laurent had to show himself in all parts of the country during elections, and following his elevation as prime minister in November, one was due in 1949. The main opposition, the Progressive Conservatives, had a new leader, former Ontario premier George Drew. Handsome and energetic, he promised a change from the Liberals who, he claimed, were tainted with Red connections in the federal bureaucracy. For the public, however, the more important issue was not the Communist menace, which was being contained overseas by NATO and vigorous diplomacy, but Canada’s abounding prosperity. The gross national product had been moving up significantly, unemployment was nearly at low wartime levels, and $634 million had been paid out in 1948 in veterans’ benefits, health services, family allowances, and old age security. On a western tour in April 1949 St-Laurent recognized this prosperity, unassailably and with a good amount of earnestness. Though in manner he was a shy, rather stiff corporate lawyer (his secretary and later biographer, D. C. Thomson, wrote of his resistance to “light conversation and exchanges of humour”), he still had a kindly, grandfatherly appearance enhanced by his immaculate attire and white moustache. During the campaign, a journalist dubbed him Uncle Louis, and the nickname stuck. On 27 June everybody’s favourite uncle led the Liberals to their greatest majority since confederation: 193 of the 262 seats in the commons and almost 50 per cent of the popular vote.

The government’s policy can be summed up as “managing prosperity,” through regular budgetary surpluses and modest improvements to social welfare programs. The provinces had blocked any progress toward a comprehensive welfare state and St-Laurent had no ambition to go farther for the time being. (His government would institute universal old-age pensions in 1951.) Foreign investment, overwhelmingly from the United States, drove the economy while exports lagged. In a soft-currency world, there were many trade barriers to be overcome, but Canada did not take the lead. Under St-Laurent and his trade and commerce minister since 1948, C. D. Howe, tariffs were still high. On the other hand, taxes remained low, certainly by comparison with Britain, the rest of Europe, and the United States, which in the 1950s had a more extensive social welfare system than Canada as well as greater burdens for defence.

As prime minister, St-Laurent continued to enjoy an unusual rapport, not just with his cabinet, but also with the senior civil service. For cabinet meetings he carefully readied himself by reading every cabinet paper and consulting with the clerk of the Privy Council and cabinet secretary. “I did my best to prepare myself,” one clerk, Robert Broughton Bryce, later recalled, “but almost invariably the Prime Minister thought of matters that I had overlooked.” Depending on the same careful groundwork that had served him so well as a lawyer, St-Laurent took the lead in discussions, introducing material, giving “the pros and cons on each item on the agenda,” outlining “his own views, and [asking] for comments,” according to Mitchell William Sharp*, who as a senior bureaucrat sometimes watched from the sidelines. “As St. Laurent hated to waste time,” noted another Privy Council clerk, John Whitney Pickersgill*, “cabinet meetings were exceedingly business-like.” Another wrote admiringly that he “handled his colleagues to a consensus with sure judgment.” Some ministers received preferential treatment, though in meetings all were accorded equal consideration. The seniors at the table were St-Laurent, Howe, and agriculture minister Jimmy Gardiner. In Gardiner’s opinion St-Laurent did not fully understand the west’s problems, but Gardiner was a loyal minister who ran his own shop and seldom interfered with others, unlike Howe. Other outstanding ministers included Brooke Claxton* in National Health and Welfare, and the charming Douglas Charles Abbott* and then the intelligent if chilly Walter Edward Harris* in Finance. St-Laurent completely trusted Pearson in External Affairs and the confidence was mutual. On the other hand, Pickersgill recalled, “some ministers were restrained by the fear of appearing ill-informed or ineffective.” St-Laurent was fortunate that his principal English-speaking colleague, Howe, had no leadership ambitions. He admired Howe’s single-minded decisiveness, and considered his services to Canada second to none. In 1951 he briefly considered making him governor general; this office was traditionally held by British aristocrats and politicians, but St-Laurent, always a positive nationalist, thought Howe had “earned” the job. Howe’s lack of tact, in reality, made him a poor choice, and the following year St-Laurent chose Charles Vincent Massey*, a wealthy Torontonian with a diplomatic background.

St-Laurent had a professional interest in the Canadian constitution, and it was to be expected that he would try to reform some of its inconveniences. The constitution, as it affected federal-provincial jurisdiction, was reserved for amendment by the British parliament under the Statute of Westminster in 1931. In the throne speech of September 1949, rejecting opposition demands that provincial consent be obtained first, St-Laurent had announced the abolition of appeals to the JCPC. There was no point in asking Quebec, he told the commons, because Maurice Duplessis would pointlessly object. At the same time he announced that he would seek an amendment to the British North America Act that would allow the Canadian parliament to change the constitution as it affected federal jurisdiction only. He convened a dominion-provincial conference in January 1950 to find a way to amend it, a goal that had escaped justice minister Ernest Lapointe as far back as 1927. These bold moves expressed a clear and uncompromising view. Still, the constitution did not have to be amended to produce practical change in the balance of power between Ottawa and the provinces. War had concentrated revenues and expenditures in Ottawa, and post-war programs, for veterans for example, had kept the balance there. In 1947 most provinces had begun to “rent” their tax revenues to Ottawa in return for compensation, a complex exchange that gave rise to agreements in 1947-51 for equalization payments to some underfinanced provinces. These agreements would be renewed with adjustments in 1952. Ontario, which under Drew had abstained from tax rental, later joined the program under St-Laurent and Premier Leslie Miscampbell Frost.

Beginning in 1950 there was even more reason for Ottawa to spend, and spend heavily. The first stage of the Cold War was diplomatic and political, more about confidence than armament. In June 1950 the war became hot, when Communist North Korea invaded anti-Communist South Korea. It was the reaction of the United States that mattered most. President Harry S. Truman surprised the Canadian government - and most of the American government - by intervening in Korea and seeking authorization for his action from the UN. Led by St-Laurent and Pearson, the Canadian government welcomed Truman’s action. Early on St-Laurent promised Canadian support, including military support, to the UN in Korea, and he announced that three Canadian destroyers would join its forces in the Far East. He made it clear that UN authority was a sine qua non for Canadian participation, but that said, the cabinet had to decide how much support to give and what its impact would be on national unity. In Quebec, nationalists compared St-Laurent’s co-operation with the United States to Canada’s old subservience to the British empire. St-Laurent paid no attention. The cabinet brushed aside fears of conscription, and authorized a larger army, an expeditionary force to Korea, a permanent garrison in Europe, and $5 billion for a rearmament program. To launch this program the government created a new department in 1951, Defence Production, and made Howe its minister. He had a reputation for imperiousness, got into trouble in parliamentary debate over the department’s establishment, and had to be rescued by the prime minister, who quieted the political waters.

The program was a success. The size of Canada’s military rose substantially, but otherwise the war did not impinge greatly on Canadian life. Relations with the United States (the alliance leader in Korea and Europe) remained calm. The American government, under both Democratic and Republican administrations, seems to have accepted Canada’s contribution as appropriate. St-Laurent in turn accepted American leadership as desirable and in any case inevitable. As he said in a speech to an American audience in 1949, “There is only one nation with the wealth and the energy and the knowledge and the skill to give real leadership, and that nation is the United States.” He confined his contacts with its presidents to bilateral issues, and rejected even the appearance of giving advice on matters of world strategy. A reluctant participant in the Canadian-American-Mexican summit in 1956 at White Sulphur Springs, W.Va, the prime minister saw it primarily as an empty photo opportunity.

Canadian-British relations were also close. The British government, which appreciated Canadian economic aid and found that Canada’s position on international matters often approximated its own, no longer tried to cast an imperial mantle over its policies. Britain was too weak to take much initiative, preferring on most matters to follow the United States and bask in the position of being its chief ally. Although St-Laurent may have been a Canadian nationalist, he was also a traditionalist; he happily hosted the visit of Princess Elizabeth in the fall of 1951 and shepherded a Canadian delegation to her coronation in June 1953. After returning home, he led the Liberals to triumphant re-election in August.

St-Laurent was 71, and he began to consider whether it might not soon be time to step down. There were loose ends to tie up, and a world tour, the first for any Canadian prime minister, beckoned. Late in 1953 he discussed his situation with Howe. They had an understanding, according to Howe, that they would both leave after a year or two in office, but “unfortunately, our leader changed his mind about retiring, which was a mistake both for him and for the party.” It did not look as if St-Laurent needed to retire. He set off on his global trip in January 1954, and he made a point of calling on India’s prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, with whom he felt a special rapport. Though Canadian policy valued India as a link between East and West and the developed North and the underdeveloped South, St-Laurent made no secret of Canada’s position in the Cold War, a fact some of his Indian hosts resented. A visit intended to bridge differences may not have done the trick, but he did not notice. He returned triumphantly to snowy Ottawa in March and settled down to business.

Business was not quite the same. The cabinet found St-Laurent had changed: he showed signs of fatigue and, worse, indifference. In debates in the commons, he sat mute, rousing himself only with difficulty to intervene. In the cabinet he sometimes stared out the window, and the meetings drifted. An alarmed Howe asked St-Laurent’s daughter in April 1954 to take him along on a vacation in Bermuda. She did, but the improvement, if any, was temporary. An agreement between an ineffectual prime minister and Duplessis in October over taxation quickly turned to the advantage of Quebec and left Liberals there feeling abandoned. Two years later, in a meeting with American president Dwight David Eisenhower, the silent and withdrawn St-Laurent presented “an almost pathetic spectacle,” Canadian ambassador Arnold Danford Patrick Heeney wrote in his diary. There is not much doubt that he was suffering from a form of depression. What brought it on is unclear, but there were plenty of things for him to worry about, most of them personal. Another daughter was unwell, the family’s finances were precarious, and there was some danger that they were spending beyond their income. The family law firm had not prospered under his sons. St-Laurent could not make up his mind what to do, and as problems were postponed, they grew.

The rush of events in 1954 masked St-Laurent’s personal issues. The Canadian and American governments concluded an agreement to build a canal and power project, the St Lawrence Seaway, which contributed to the country’s apparently unending prosperity. At the same time the seaway underlined St-Laurent’s seeming disregard for western Canada, especially the South Saskatchewan water and hydro project, which Jimmy Gardiner had been pushing ceaselessly. Politically, two of the mainstays of St-Laurent’s cabinet chose to retire in June, Douglas Abbott to the Supreme Court and Brooke Claxton to business. St-Laurent was grieved at their departures, which unquestionably affected the government’s effectiveness. This change in personnel also modified expectations for the eventual succession to the prime ministership, leaving only Pearson from the cabinet’s front rank to aspire to the position. (It was well known that Gardiner and Paul Martin also had ambitions in this direction, but their colleagues did not take their prospects seriously.) Suddenly the cabinet took on a patina of age, with half its members near or over 65. Matters drifted. The give-away of wheat by the United States (to subsidize American farmers) undermined exports from western Canada, St-Laurent’s protests to the American government were unavailing.

St-Laurent’s increasingly indifferent direction placed more of a burden on individual ministers, especially Howe, who was not in the best of health himself. The government’s solidarity began to leach away, though the decline was unreflected in public opinion polls, where the Liberals continued to lead, as they had since 1944. Such public projects as the Trans-Canada Highway, the Distant Early Warning Line for air defence, and the Canso Causeway in Nova Scotia drew favourable attention, and Howe was concentrating on a project designed to bring natural gas through a transcontinental pipeline from Alberta to central Canada. It would simultaneously give the country security of energy supply and improve its balance of payments by replacing coal and gas imported from the United States. To do the job, Howe had helped design a private company, Trans-Canada Pipe Lines Limited, incorporated in 1951. Much of the money and most of the technology would come from the United States, but a crucial part of the funding, for the section passing through unpopulated northern Ontario, where there was no supporting market, would have to be provided by Ottawa.

In the spring of 1956 Howe introduced legislation to provide Trans-Canada with the necessary federal cash. St-Laurent had no objection, and left the matter to his colleague. This was a mistake. There was a deadline on assembling the money, in order to start construction that summer, and all the opposition had to do was delay the bill. To get it passed, the government, again with St-Laurent’s acquiescence rather than his leadership, used the then unusual parliamentary device of closure to limit discussion. The move was a public-relations disaster. As debate raged in the house, St-Laurent sat abstracted, though when he finally roused himself to speak, he uttered a dignified and authoritative summary of the issue, with reasons why the government had to proceed as it did. The majority as well as the minority, he reminded members, had rights and they included the right to pass legislation. The bill passed, and the pipeline eventually snaked from west to east. The government had had its way, but at some cost to its reputation. Opinion polls held, and attempts by the Conservatives to bring on an election foundered on contradictions within their party. In condemning the pipeline, some of them raised the spectre of too close a relationship between the Liberals and the Americans, symbolized by Howe, an immigrant from Massachusetts. That need not have mattered, but in the fall of 1956 the American issue was linked to the question of Canada’s traditional association with the British empire, a subject on which the prime minister now had definite views.

St-Laurent had generally maintained amicable relations with his British counterparts, including the prime minister from 1955 to 1957, the ageing Robert Anthony Eden. Eden tried to rationalize Britain’s foreign commitments, to bring them more into balance with his country’s reduced economic resources. In particular, he had withdrawn the large garrison around the Suez Canal on Egypt’s promise to leave this piece of British property alone. In July 1956, however, the Egyptian government nationalized the canal. Eden’s reaction to this intended provocation was entirely disproportionate. He immediately prepared, with the French, to invade Egypt. Objections were brushed aside and knowing that the Canadians were likely to complain, he told his staff not to inform them; the Americans too were kept in the dark as much as possible. By late October, the British and French had arranged an Israeli invasion of Egypt and, using it as an excuse, they proclaimed they were intervening to protect the canal against a war. Eden sent St-Laurent a letter asking for Canadian understanding.

Eden had deliberately deceived him and Pearson had to work to contain his chief’s fury, while sharing it himself. Pearson prepared a temperate response, placing Canadian policy within the framework of the UN and declining to support the Anglo-French action. When St-Laurent and Pearson brought the issue before the cabinet, some English-speaking ministers argued that such a stand would offend traditionalist Canadian opinion. At the UN, Pearson introduced a proposal for a peacekeeping force that would replace the British and French troops around the canal and cover Israel’s withdrawal. His work drew compliments from around the world, but not in Canada, where the Conservatives, now under John George Diefenbaker, a veteran Saskatchewan mp, made the government’s failure to support Britain the issue. This time St-Laurent was not indifferent. Rebutting Conservative arguments, he told the house on 26 Nov. 1956 that he had been scandalized by the big powers, “who have all too frequently treated the charter of the United Nations as an instrument with which to regiment smaller nations.” In response to the derisive interjection from across the floor, asking why the big powers should not be allowed to veto action by the smaller nations, St-Laurent, according to an eyewitness, squared his shoulders defiantly, reddened, and retorted, “Because the era when the supermen of Europe could govern the whole world is coming pretty close to an end.” Nothing he said was untrue, but in the heated atmosphere of the nostalgic imperial patriotism that was sweeping through parts of English Canada, he had waved a red flag at a political bull.

The next six months were taken up with housekeeping and anticipation of an election. A Liberal gala in Quebec City to celebrate St-Laurent’s 75th birthday featured an eloquent speech by Howe, who boasted that his friend stood “in the shade of no man.” This was St-Laurent’s last hurrah, but no thought was being given to replacing him so close to the election, set for 10 June 1957. The Liberals were ahead in the polls, and St-Laurent was considered to be one of his party’s major assets. One minister reportedly said in private that the party would go with St-Laurent if it had to run with him stuffed. The contest was Canada’s first televised election. St-Laurent did not make much of an impression on the new medium, though the polls, right up to the end, indicated voters still intended to cast their ballots for the Liberals. For the campaign the party had money, but no workers; few of the ministers had much impact outside their ridings, and many stalwarts were dead. Worse, on a variety of issues the Liberals had offended the electorate, from wheat sales (or the lack of them) to the pipeline to the Suez crisis. No single issue would have been fatal, but the combination, joined to an uninspired campaign and an abstracted leader, proved indigestible. As the prime minister travelled through English Canada, hecklers yelled out “supermen,” referring not just to his remark about the supermen of Europe but sarcastically to the Liberals as the supermen of Canada. At what should have been the Liberals’ climactic rally, in Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens, St-Laurent looked and sounded out of touch. As Jack Pickersgill later wrote, “John Diefenbaker did not win the election of 1957; the Liberal party lost it.” They won more votes than the Conservatives but fewer seats. Half the cabinet was defeated, though St-Laurent comfortably took Quebec East. After a pause, while close races were decided, he determined to leave office. On 21 June the cabinet resigned, Diefenbaker took over, and St-Laurent moved into the unaccustomed job of opposition leader.

St-Laurent spent the summer at Saint-Patrice. In August, Pickersgill visited him there: “He was obviously deeply depressed, could not be drawn into conversation, and clearly had no interest in his new role.” St-Laurent’s family now took a hand. They invited two former ministers, Lionel Chevrier and Pearson, to visit and try to persuade their leader that he would not be deserting the party if he resigned. The family asked Pearson to draft a statement of resignation; St-Laurent stared at it, and then gave his consent. According to Chevrier, he did so only after Pearson, whom he considered his logical successor, agreed that he would run to replace him. St-Laurent served as opposition leader for the fall session. At the Liberal convention of January 1958 Pearson was chosen leader, but Diefenbaker did not give him much time to adapt. Taking advantage of some Liberal blunders, he called a new election for 31 March, in which he trounced the Liberals. St-Laurent, who did not run, returned to Quebec and the practice of law.

He was not quite starting over, but even with his prestige he had to cope with the handicap of age. Nevertheless, for some years he practised as he once had, attempting to restore the family fortunes. Old colleagues dropped in from time to time, and among the ministers and mandarins of Ottawa his memory remained green. Apart from them, the ex-prime minister was gradually forgotten. He sometimes attended funerals, including Howe’s in Montreal in January 1961, and was occasionally invited to state occasions, such as the banquet honouring the visit of French president Charles de Gaulle in Quebec in 1967. His wife died in 1966. Still, in some respects his health and mood improved after he left office. He greeted visitors equably. “I’m just as bright, just as active as I ever was,” he told Pickersgill. “And you know, Jack, I’m like that for an hour every day.” His firm’s fortunes improved, permitting him gradually to fade into the background and let his son Renault-Stephen take the lead. Finally, after years out of the public eye, Louis St-Laurent died in July 1973.

St-Laurent had many of the best characteristics of a prime minister but few of the best attributes of a politician. In his most productive years in the job, 1948 to 1954, he presided over a cabinet of strong ministers, many of them first-class politicians. His views and theirs generally coincided, though when they did not, it was the prime minister who prevailed. His fundamental commitment was to national unity, which he interpreted broadly in terms of an expansive federal power. At home and abroad he was an activist, which an abundant economy allowed him to be. More than any prime minister since, St-Laurent dominated his cabinet and his party. When he entered the room, Liberal mps stood up in a sign of respect, if not reverence. He was able to master his cabinet in part because he was the master of the issues before it, an authority derived from intelligence and application. St-Laurent also had that most valuable asset, good luck; he served in good times and undoubtedly reaped political rewards from this prosperity. When he had to confront a difficult opposition, his qualities could no longer be mobilized to the task. As a politician, he alternated between two roles, corporate counsel and paterfamilias, without the dynamism of Diefenbaker, who was a superior campaigner and debater. St-Laurent was at his weakest in dealing with practical politics, and he failed to recruit replacements or alternatives for some of his ageing ministers. Because the Liberals depended on regional leaders to rally local support, this was a serious failure.

It was St-Laurent’s misfortune to stay in office too long. Afflicted by a form of depression, he was unable to make the best choices for his party or himself, although, where the country was concerned, even his most controversial policies - the pipeline and opposition over Suez - were arguably the right ones. St-Laurent’s time as prime minister passed from public consciousness, remembered if at all as a comfortable era of placid prosperity. Perhaps even the worst prime minister could not have avoided the prosperity, but placidity and comfort are not a bad inheritance to pass to posterity.

The bibliography of Louis St-Laurent is lamentably brief. He is the author of The foundations of Canadian policy in world affairs ([Toronto], 1947) and a selection of his early speeches was published in The Liberal Party personalities and policies: speeches by W. L. Mackenzie King and Louis S. St. Laurent ([Ottawa, 1946?]). There is one standard biography by his former secretary, D. C. Thomson, Louis St. Laurent: Canadian (Toronto, 1967). Thomson had the great advantage of being an eyewitness of the events he described, as well as having contact with St-Laurent on a daily basis. As principal secretary in the Prime Minister’s Office, Thomson presided over the files and was in charge of moving them when St-Laurent ceased to be prime minister in 1957. Those that survived the move do not present a complete record of St-Laurent’s time as prime minister. The best that can be said is that they are spotty; occasionally, they are entirely lacking. They are preserved at Library and Arch. Canada (Ottawa), MG 26, L. There is a great deal of information in Thomson’s biography, based on his personal familiarity with the subject, that cannot be found anywhere else.

The second essential book on St-Laurent is J. W. Pickersgill, My years with Louis St-Laurent: a political memoir (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1975). Pickersgill was clerk of the Privy Council and later a minister under St-Laurent, and he kept up an acquaintance with him until the latter’s death. His book represents the common view among the senior civil servants in Ottawa of St-Laurent’s character and achievements. “Jack thought St-Laurent was his mother,” Thomson once quipped, and certainly the portrait Pickersgill paints is affectionate, though not entirely uncritical.

St-Laurent’s life is best remembered in terms of his impact on others, or in terms of its effects. Three biographies, Robert Bothwell and William Kilbourn, C. D. Howe: a biography (Toronto, 1979), D. J. Bercuson, True patriot: the life of Brooke Claxton, 1898-1960 (Toronto, 1993), and John English, The life of Lester Pearson (2v., Toronto, 1989-93), contain material bearing on St-Laurent’s performance as a minister and prime minister. A more general assessment of the St-Laurent government may be found in Bothwell et al., Canada since 1945: power, politics and provincialism (rev. ed., Toronto, 1989).

Cite This Article

Robert Bothwell, “ST-LAURENT, LOUIS-STEPHEN (baptized Louis-Étienne),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 20, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 12, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/st_laurent_louis_stephen_20E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/st_laurent_louis_stephen_20E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert Bothwell |

| Title of Article: | ST-LAURENT, LOUIS-STEPHEN (baptized Louis-Étienne) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 20 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 12, 2025 |