Source: Link

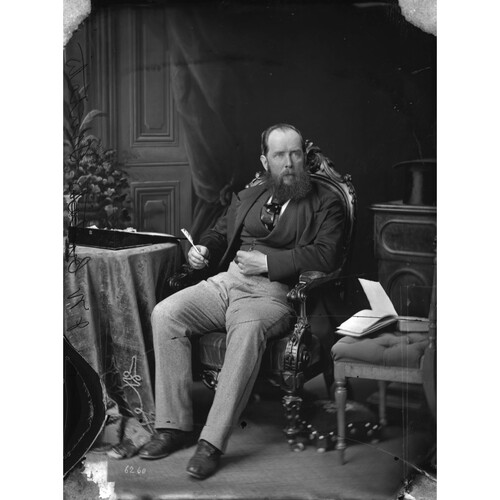

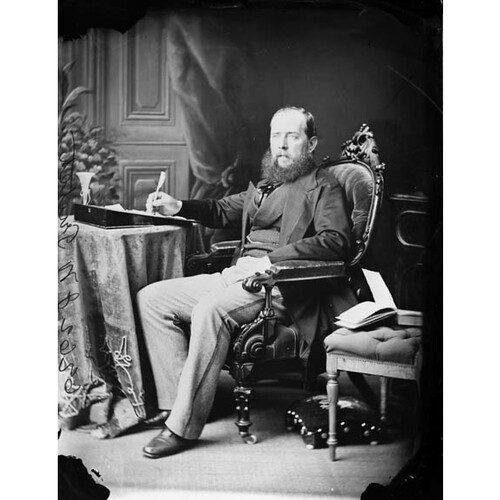

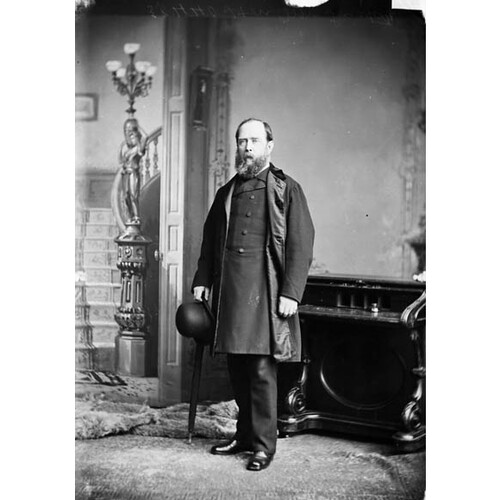

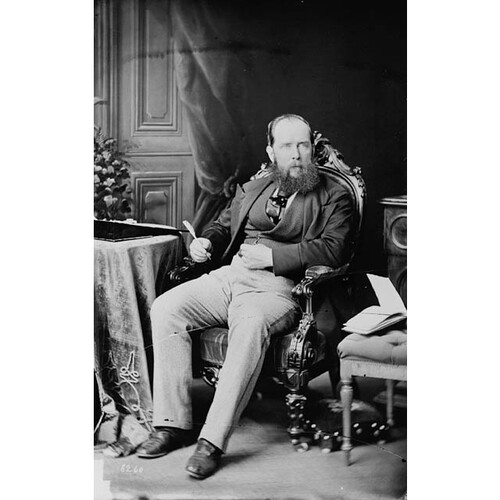

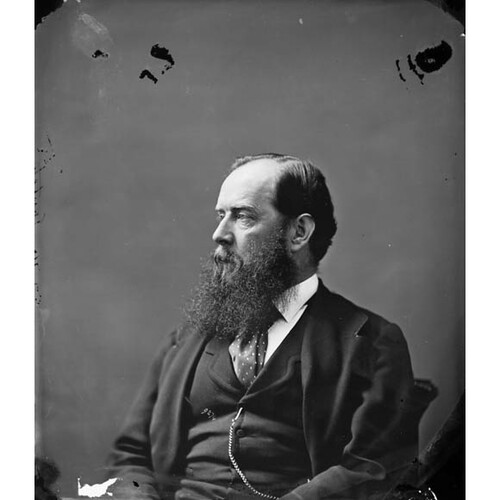

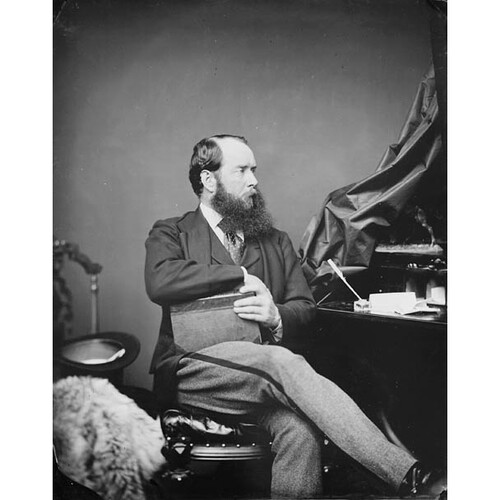

TRUTCH, Sir JOSEPH WILLIAM, engineer, surveyor, politician, and office holder; b. 18 Jan. 1826 in Ashcott, England, son of William Trutch and Charlotte Hannah Barnes; m. 8 Jan. 1855 Julia Elizabeth Hyde in Oregon City, Oreg.; they had no children; d. 4 March 1904 in Taunton, Somerset, England.

Joseph Trutch was a particular colonial type. An Englishman who lived most of his life in far-flung parts of the empire, he saw the colonies as places of opportunity and advancement but not of permanent commitment. He became an influential figure in colonial British Columbia, part of his legacy being the aboriginal land question that still troubles the province. He amassed great wealth, belonged to Victoria’s social élite, was a key politician of the confederation era, and became lieutenant governor in 1871. And yet, for all of his success in the colonies, he eventually returned “home” to England to live out his retirement years.

Trutch spent much of his early childhood in Jamaica, where his father was a landowner in the parish of St Thomas. In 1834 the family returned to Britain. They settled in Somerset and Trutch went to grammar school at Mount Radford College-School in Devon. When he left school, Trutch was apprenticed to Sir John Rennie, a prominent British engineer, and worked on the Great Northern and Great Western railways. His thoughts began, however, to turn to North America which, like many others, he saw as a land of greater opportunity. His interest was further stimulated by the California gold-rush of 1849, and before the end of the year he was on his way to the west coast.

Trutch was in his mid twenties when he arrived in San Francisco. During the nine years that he lived in the United States, two things about him became apparent: his desire to make the “right” connections and his disdain for native people. He thought that San Francisco was an uncouth place and its citizens rude and vulgar. Part of his problem, he believed, was that he was not meeting the right kind of people. As he explained to his parents, “If I could get known among the best people, I mean the capitalists, I should be sure to do well.” Within a few months he moved to Oregon Territory, which he found more in keeping with his notion of a frontier of opportunity. He secured employment in his profession, beginning with contracts to survey and construct the town-sites of St Helens, Oreg., and Milton, Wash., and then, in 1852, he was hired as assistant surveyor in the surveyor general’s office.

Working around the mouth of the Columbia River and in the Puget Sound area, Trutch came into contact with the native Indians. He was not impressed. He had written to his parents a few weeks after arriving in Oregon Territory that he thought the native people were “the ugliest & Laziest creatures I ever saw, & we shod. as soon think of being afraid of our dogs as of them.” Like many Europeans coming to new frontiers, Trutch held stereotypes of native people that were never modified by firsthand experience.

Meeting the right people among the non-native population of Oregon Territory did advance his career. Trutch’s work impressed his supervisor, John Bower Preston, who was a member of a prominent Illinois family. The contact with Preston also changed his personal life. Trutch met Preston’s sister-in-law, Julia Hyde of New York, and in 1855 the two were married. The couple settled in Illinois, where Trutch again worked for Preston. He was assistant superintendent on the western division of the Illinois and Michigan Canal. He also joined Preston in land speculation in the Chicago area. And yet he was still not happy in the United States. Business was dull and the cold climate affected his health.

When the Fraser River gold-rush began in the spring of 1858, Trutch was attracted to the new colony on the west coast. British Columbia, he wrote to his brother John, who later joined him there, seemed like a place where Englishmen could live “under our own laws and flag,” and he hoped to “make something out of this gold excitement.” He went to London to discuss his prospects with officials at the Colonial Office. There were no positions available, but he did receive a recommendation from Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton, the secretary of state for the colonies, to James Douglas*, the governor of British Columbia and Vancouver Island. He also met Richard Clement Moody*, who had been placed in command of a detachment of Royal Engineers being sent to British Columbia and been appointed chief commissioner of lands and works as well. Once again he was making the right contacts.

Trutch arrived in British Columbia in June 1859 and would spend most of his next 30 years on the west coast. While he would play a number of roles in the colony, he began by pursuing his career as an engineer and surveyor. Without a permanent position in the colonial service, he worked on government contracts. He did surveying along the lower Fraser River and was given road construction contracts on the Harrison-Lillooet trail to the Cariboo. In 1862 he was contracted to build the section of the Cariboo Road up the Fraser canyon from Chapmans Bar to Boston Bar. The stretch would include his best-known engineering achievement, the Alexandra suspension bridge. With a 268-foot span, a 90-foot clearance from the river, and a 3-ton load capacity, the bridge was a considerable feat. It was also a source of considerable income for Trutch since under the contract he was allowed to collect tolls on it for seven years. The income has been estimated to have ranged from $10,000 to $20,000 a year. Moving about on survey work, Trutch learned where desirable land was to be found and he soon amassed substantial holdings, particularly on Vancouver Island.

Trutch also became involved in colonial politics. He had won a by-election in Victoria District in November 1861 to become a member of the Vancouver Island House of Assembly. His construction work took him out of Victoria a great deal and he was an infrequent attender of the meetings but, once again, he made important contacts. Although his first foray into politics ended with the dissolution of the assembly early in 1863, another opportunity came when Moody and the Royal Engineers were recalled to Britain later the same year. Trutch was named by Governor Douglas to the vacant position of chief commissioner of lands and works for British Columbia in April 1864. The appointment was a controversial one. In the local press, opponents of the colonial administration argued, not unreasonably, that Trutch’s government contracts and large landholdings meant he would have an obvious conflict of interest. Nevertheless, in a colony where expertise was limited, Trutch’s undoubted ability as a surveyor and engineer got him the office. He was now in a position to make major decisions on the allocation of land to settlers and works contracts to developers. The dismay of his detractors was only partly assuaged when Trutch proposed to hand his interest in the Alexandra suspension bridge over to his brother John. As chief commissioner of lands and works he also became, ex officio, a member of the Executive Council of British Columbia.

In addition to entering the colonial administration, Trutch had become a prominent figure among the social élite of Victoria. Indeed, the two groups were closely related. His home, Fairfield House, on the city’s outskirts commanded a superb view of Juan de Fuca Strait and became a centre of social life. Trutch smoked fine cigars, kept an excellent wine cellar, and entertained often. An Anglican, he often read the lesson at Christ Church Cathedral on a Sunday morning. Members of the government, from Governor Douglas down, were among his personal friends and it was a close-knit community. The attorney general, Henry Pering Pellew Crease, had been a friend since their school-days together at Mount Radford. Peter O’Reilly, the gold commissioner, married Trutch’s sister Caroline Agnes in 1863. In 1870 Trutch’s brother John married Zoe Musgrave, the sister of Anthony Musgrave*, the last colonial governor of British Columbia. These were the people who ran British Columbia and they ran it in their own interests and those of their class. Anyone who stood in the way of the development of the colony was likely to get short shrift from Joseph Trutch and his kind.

In many ways, Trutch left his most lasting legacy to British Columbia in the area of Indian land policy. Just after Trutch became chief commissioner of lands and works, Douglas retired. As governor, he had made that policy. Though he had discontinued his early practice of signing treaties with native people to extinguish their title to the land, he had continued to take their wishes into account when laying out reserves, and he insisted that, once established, Indian reserves were to be protected from encroachment. Douglas believed that native people would have some future in the colonies and wanted to provide at least a minimal economic basis for it. Trutch, as the representative of the new settler society, thought that the Indians should simply make way for the white population. After Douglas left office, none of his successors as governor had the same interest in native people or policy, and so Trutch stepped in to fill the vacuum of leadership.

There were two major features to Trutch’s Indian land policy in the 1860s. First, he confirmed the practice of not recognizing aboriginal title and, second, he made sure that Indian reserves were of minimal size. He believed that native people in British Columbia had no valid claim to the land and therefore it was unnecessary to negotiate agreements or offer compensation, either to extinguish aboriginal title or to reduce existing reserves. Thus the policy of not signing treaties, begun under Douglas, was continued. On the issue of reserve size, however, Trutch instituted a clear change. He took the view that the reserves already laid out were “entirely disproportionate to the numbers or requirements of the Indian Tribes.” Even more important, they included good arable and grazing land that ought to be made available to white settlers. He cut back the size of many, beginning with Shuswap reserves in the Kamloops area and continuing the process in the Fraser valley. Native objections were ignored and Trutch deliberately falsified the record of Douglas’s dealings in an effort to justify the change in policy. Though few complained at the time, he left British Columbia with a legacy of litigation and a political problem that is unresolved to the present day.

Taking reserve land from Indians and giving it to settlers did not, of course, hurt his popularity in his own community. Trutch was growing increasingly prominent in the Legislative Council of British Columbia, of which he had become a member in 1866, and he would play an important role in the major issue facing the settler population of British Columbia by the end of the 1860s. As the gold-rush had fizzled out, a depressed economy created massive financial problems for government that the uniting of the two colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia in 1866 had failed to alleviate. There was the need for another political solution to the economic crisis and, with the achievement of the Canadian confederation in 1867, joining the new nation became a possibility. Trutch, and the other British officials, initially opposed any loosening of ties to Britain. They cloaked their fear of losing their lucrative positions in the mantle of imperial sentiment. Annexation by the United States, another possibility being advocated by a few, was, of course, anathema to Trutch. And yet some change had to be made. British Columbia could not continue as an isolated British colony with a declining economy.

Matters came to a head with the appointment of Musgrave as governor in 1869. He was instructed to engineer British Columbia’s entry into confederation. Trutch and Musgrave became friends and, with the marriage of their siblings, relatives. Musgrave also guaranteed the future of Trutch and the other colonial officials with the promise of a position or a pension after British Columbia became a province of Canada. With the threat to his self-interest removed, Trutch became an ardent advocate of union with Canada. He was a forceful speaker when the question was debated in the Legislative Council and was a particularly strong proponent of a railway link. Once the council had voted in favour of joining confederation, Musgrave appointed Trutch, John Sebastian Helmcken*, and Robert William Weir Carrall* to negotiate the proposed terms of union with the federal government in Ottawa.

Trutch was effectively the head of the delegation. Helmcken admitted that he was “head and shoulders above us in intellect – and pertinacity” and so, once in Ottawa, “Trutch was everything and everybody.” He pressed the federal government on building a transportation link to British Columbia and, to his surprise, was offered more than he asked for. The dominion promised to begin constructing a railway within two years and finish it in ten. He was also the author of the unfortunate clause 13 of the terms of union which, in handing responsibility for Indians and Indian land over to Ottawa, stipulated that the federal government would adopt “a policy as liberal as that hitherto pursued by the British Columbia Government.” It was some years before federal officials realized just how illiberal Trutch’s Indian policy had been. After the terms of union had been approved in Victoria, Trutch returned east and gave his personal assurance that British Columbia would not hold Ottawa to a literal interpretation of the railway clause. This undertaking produced consternation on the west coast but facilitated the passage through the Canadian parliament of the address to the queen recommending British Columbia’s entry into confederation. Having concocted a misleading clause on native policy, he had no need to reassure the federal government on that score. Trutch continued to believe that British Columbia’s future lay in taking land from native people and making it available to developers such as railway companies.

British Columbia became the sixth province of Canada on 20 July 1871. Joseph Trutch was rewarded by the federal government with appointment as the first lieutenant governor. He was reluctant to accept the post since he would have preferred a more lucrative role in building the proposed railway. His selection was not popular in all quarters. Provincehood was to be accompanied by the institution of responsible government, which Trutch had opposed before 1871. His political opponents thought that he now dragged his feet on the issue and there was no doubt that he continued to play a major role in politics. Prior to the first election Trutch appointed the ministers of the crown and his influence resulted in John Foster McCreight*’s becoming the first premier. As his friend Crease put it, “Trutch still runs the mill . . . it’s a one man government still (in disguise).” But the defeat of the McCreight ministry late in 1872 led to Trutch’s calling on the mercurial reformer Amor De Cosmos* to form a government. De Cosmos had been pressing for years to have political power removed from the hands of unelected officials and he was determined that Trutch should not exceed his constitutional role.

Trutch’s political influence was waning and the other aspects of his office did not compensate. He was responsible for setting up federal institutions in British Columbia, and he was Ottawa’s minister of patronage in the province. He continued to have an influence on Indian land policy. As lieutenant governor he was also the agent of the imperial government and was a strong advocate of the British case against the United States in the San Juan Island and Alaska boundary disputes. And yet he was becoming bored with his position, which no longer demanded all his energy. Some more challenging business enterprise would have been more to his liking. His enthusiasm was piqued by Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald*’s plans to establish the Canada Pacific Railway Company and he assisted by raising some of the preliminary capital in British Columbia. But the scheme went up in smoke with the Pacific Scandal of 1873. When Macdonald and the Conservatives were replaced by the Liberals under Alexander Mackenzie*, the railway was on hold and Trutch had lost his influential contacts in Ottawa.

Though he probably would have preferred to relinquish the position, he stayed on as lieutenant governor until the end of his five-year term in 1876. Prospects, particularly lucrative ones, appeared to be limited in British Columbia and so it seemed “in all respects but climate, a good place to leave.” He therefore returned to England in the hope of appointment by the British government to some imperial post. But it was the return of Macdonald and the Conservatives to power in 1878 that brought him another opportunity. He was appointed dominion agent in British Columbia in 1880 with particular responsibility for railway matters. He was also to take an advisory interest in Indian issues on behalf of Ottawa. Trutch still did not “consider it of special moment to secure extensive tracts of land for the Indians,” and to ensure that his view prevailed he had his brother-in-law, Peter O’Reilly, selected as Indian reserve commissioner. Trutch’s major duty was, however, to supervise the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway through British Columbia and the management of the lands transferred to the federal government under the various railway agreements. It was he who was responsible for the inclusion of the Peace River block in those lands in compensation for tracts already alienated or deemed to be unproductive in the railway belt in southern British Columbia.

Trutch retained his federal position in the province until 1889. When he left office he was awarded a knighthood for his services to Canada and British Columbia. Yet he returned to England to live the rest of his life. He visited Victoria only once more, apparently at the request of his ailing wife, who died there in 1895. He maintained an interest in developing commercial ventures in British Columbia, heading up a British syndicate that financed the operation of the Silver King Mines in West Kootenay. But he did not wish to live on the Pacific coast again. Though Canada’s westernmost province had been the scene of much of his active career, in many ways he had never left the place of his birth. Joseph Trutch died on 4 March 1904 in Somerset, the same English county in which he had been born 68 years earlier.

BCARS, C/AB/30.7J/10, Trutch to acting colonial secretary, 17 Jan. 1866. NA, MG 26, A, 279. Univ. of B.C. Library, Arch. and Special Coll. Div. (Vancouver), M643 (Trutch family papers), esp. folders 1–29, 1–32, 1–44, 1–56. G. S. Andrews, Sir Joseph William Trutch . . . a memorial apropos the 1871–1971 centenary of British Columbia’s confederation with Canada ([Victoria], 1972). B.C., Legislative Assembly, British North America Act, 1867, terms of union with Canada, rules and orders of the Legislative Assembly, Treaty of Washington (Victoria, 1881), 66; Legislative Council, Debate on the subject of confederation with Canada (Victoria, 1870; repr. 1912), 17–22, 75–76, 81. R. [A.] Fisher, “Joseph Trutch and Indian land policy,” BC Studies, no.12 (winter 1971–72): 3–33. J. S. Helmcken, The reminiscences of Doctor John Sebastian Helmcken, ed. Dorothy Blakey Smith, intro. W. K. Lamb ([Vancouver], 1975). J. T. Saywell, “Sir Joseph Trutch: British Columbia’s first lieutenant-governor,” BCHQ, 19 (1955): 71–92.

Cite This Article

Robin Fisher, “TRUTCH, Sir JOSEPH WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 6, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/trutch_joseph_william_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/trutch_joseph_william_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robin Fisher |

| Title of Article: | TRUTCH, Sir JOSEPH WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | January 6, 2025 |