Source: Link

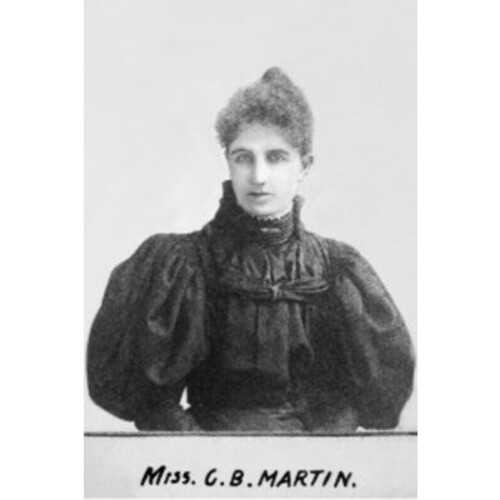

MARTIN, CLARA BRETT, lawyer and office holder; b. 25 Jan. 1874 in Toronto, daughter of Abraham Martin and Elizabeth Brett; d. there unmarried 31 Oct. 1923.

Clara Brett Martin was the youngest of the 12 children of Anglican Irish farmers in Mono Township. The family, who moved to Toronto in the early 1870s, prized schooling: Clara’s father had been a township superintendent of education and at least three of her siblings became teachers. In an era when less than one per cent of the Canadian population undertook post-secondary education, all of the Martin children spent some time at university. Clara entered Toronto’s Trinity College in 1888, a mere three years after it had begun to admit females. Women’s efforts to enrol in universities inspired considerable controversy at the time; physicians speculated that higher education would weaken them physically and mentally. Defying all predictions, the young Clara, who would later be pronounced attractive, graceful, and possessed of “treasured feminine charms,” majored in mathematics and graduated with a ba and high honours on 27 June 1890, at the age of 16.

In Hilary term 1891 Martin petitioned the Law Society of Upper Canada to admit her as its first female student-at-law. A committee chaired by Samuel Hume Blake* refused her request in June and advised that she should seek legislative clarification of women’s access to the profession. William Douglas Balfour*, the mpp for Essex South, introduced a bill in March 1892 stipulating that women be admitted to the practice of law. The bill was subjected to a blistering attack from opposition leader William Ralph Meredith. Nature, he insisted, dictated that admission to law would prove “disastrous to the best interests of women,” and he conjectured that fashion-conscious women would never want to wear the same official robes as male litigators. Martin found support in many powerful quarters, however, including Dr Emily Howard Stowe [Jennings*], a leading proponent of the women’s movement, and Oliver Mowat*, Ontario’s premier and attorney general. In the end a compromise statute was enacted on 13 April 1892 that gave the society the discretionary power to admit women to the level of solicitor.

The recalcitrant benchers of the society met five months later, deliberated over the permissive wording of the legislation, and then voted to deny Martin’s application of 21 June on the grounds that it was “inexpedient” to frame rules for admitting women. Mowat appeared before the society’s convocation on 9 December to argue Martin’s case. After a heated discussion, the vote on the motion for admission came out as a tie. Chair Æmilius Irving* broke the impasse in favour of the motion, prompting the Western Law Times of Canada (Winnipeg) to regret that the entry of women had been occasioned by a single vote, which represented neither “the wishes of a large majority of the profession” nor the will of the benchers “if they only had the manliness to speak out.”

Martin began articling in June 1893 with the Toronto firm of Mulock, Miller, Crowther, and Montgomery, but the unpleasant treatment she received there from her articling peers and the firm’s secretaries forced her to switch to Blake, Lash, and Cassels. Sitting through lectures at Osgoode Hall was no easier: students hissed when she entered the room and some lecturers attempted to humiliate her by emphasizing points relating to sex. Martin passed her examinations handily despite this abuse, and she would go on to obtain a bcl from Trinity in 1897 and an llb from the University of Toronto in 1899.

Eligible to be admitted as a solicitor in June 1896, she chose instead, while completing her articles, to join battle once more with the Law Society and seek admission as both a barrister and a solicitor. The widespread lobbying required for yet another legislative enactment elicited support from Lady Aberdeen [Marjoribanks*] (the wife of the governor general) and the members of the National Council of Women of Canada and the International Council of Women. In March 1895 William Bruce Wood, the mpp for Brant North, brought in a bill to permit the society to admit women as barristers. After considerable debate over the dangers female litigators might pose to the “homes and womanhood of Ontario,” the measure passed, and received royal assent on 16 April. The society continued to drag its feet, first exercising its discretion to refuse Martin’s call as a barrister, and then sending the matter to committee. The benchers finally caved in to pressure from Mowat and a skilfully mounted public lobby. On 2 Feb. 1897, at 23, Clara Brett Martin was admitted as a barrister and a solicitor, the first woman in the British empire to achieve such status.

She began practice with the Toronto firm of Shilton, Wallbridge and Company, became a partner in 1901, and left to set up her own office in 1906. Her practice centred on wills, real estate, and family law. The profession she had joined was viciously anti-Semitic, and she shared much of its hostility to Jews. One of the few surviving letters from her business files is a missive in 1915 to Edward Bayly*, solicitor to the attorney general’s department, in which she accused certain Jewish realtors of transferring property titles improperly and misleading some of her clients about outstanding claims. She asked that the registry act be amended to prevent “such scandalous work” by Jewish “foreigners.”

A frequent lecturer to women’s organizations, Martin hired a number of female articling students and joined with advocates of women’s rights to lobby for female suffrage and a separate court for women within the Toronto Police Court. In an article written for the National Council of Women in 1900, she attacked the dual standard of sexuality in law, in particular the legal disadvantages of married women and the supremacy of paternal rights in cases involving child custody. Law and women’s rights, however, were not her only interests. In the 1890s, while living on Homewood Avenue with her mother and brother Robert Thomas, a school principal, she had joined her family’s long-running involvement in education. She was a member of the Toronto Collegiate Institute Board in 1896–99 and of the Public School Board in 1901–10. During her time with these boards she achieved a reputation as a path-breaker in the field of equal intellectual rights for women. In 1920 she ran as an aldermanic candidate in Ward 2 but was narrowly defeated.

Clara Brett Martin died at age 49 of a heart attack at her home on Roxborough Street East and was buried in St James’ Cemetery. She had bequeathed her property to her unmarried sister Fanny. Extensive obituaries in Toronto newspapers lamented her passing as the loss of a trailblazer for women in professional life.

Family information concerning Clara Brett Martin was supplied to the author in a letter of 9 Aug. 1984 from Betty L. Hall of Lockport, N.Y., a great-niece of the subject. The issue of Martin’s anti-Semitism is discussed in a series of articles in the Canadian Journal of Women and the Law (Ottawa), 5 (1992): 263–356.

Martin’s publications include “Legal status of women in the provinces of the Dominion of Canada (except the province of Quebec),” in National Council of Women of Canada, Women of Canada: their life and work; compiled . . . for distribution at the Paris International Exhibition, 1900 (Montreal?, [1900?]; repr. [Ottawa], 1975), 34–40, and “Women in law,” an undated clipping from the Illustrated Buffalo Herald (Buffalo, N.Y.) preserved in Martin’s file in the archives of the Women’s Law Assoc. of Ontario, Toronto.

AO, RG 80-8-0-912, no.6854. Toronto Board of Education, Records, Arch., and Museum, Toronto Collegiate Institute Board, minutes, 1896–98; Toronto Public School Board, minutes, 1901–10. Evening Telegram (Toronto), 31 Oct., 1 Nov. 1923. Globe, 18 Feb. 1910; 1–2 Nov. 1923. Toronto Daily Star, 24 April 1914, 1 Nov. 1923. Alexandra Anderson, “The first woman lawyer in Canada: Clara Brett Martin,” Canadian Women’s Studies ([Toronto]), 2 (1980), no.4: 9–11. Constance Backhouse, Petticoats and prejudice: women and law in nineteenth-century Canada ([Toronto], 1991), 293–326; “‘To open the way for others of my sex’: Clara Brett Martin’s career as Canada’s first woman lawyer,” Canadian Journal of Women and the Law, 1 (1985–86): 1–41. Isabel Bassett, The parlour rebellion: profiles in the struggle for women’s rights (Toronto, 1975). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). Directory, Toronto, 1888–1923. “Laws affecting women in Ontario,” Canadian White Ribbon Tidings (Toronto), 1 Aug. 1912: 2258. Theresa Roth, “Clara Brett Martin – Canada’s pioneer woman lawyer,” Law Soc. of Upper Canada, Gazette (Toronto), 18 (1984): 323–40. H. R. S. Ryan, “A pilgrim’s progress” (transcript, n.d.; copy in Queen’s Univ. Arch., Kingston, Ont.). Types of Canadian women . . . , ed. H. J. Morgan (Toronto, 1903).

Cite This Article

Constance Backhouse, “MARTIN, CLARA BRETT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 7, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/martin_clara_brett_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/martin_clara_brett_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Constance Backhouse |

| Title of Article: | MARTIN, CLARA BRETT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | February 7, 2026 |