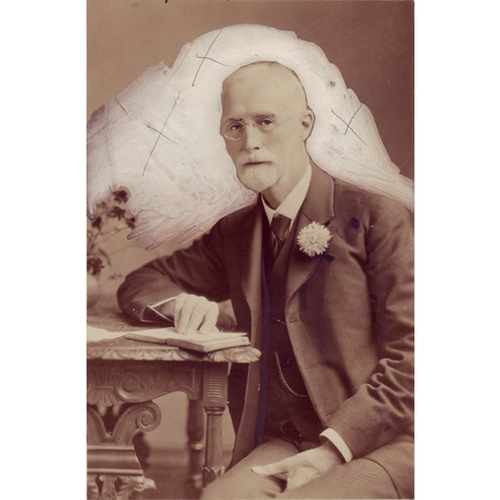

![Portrait photograph of Dr. Newman Wright Hoyles (1844-1927), principal of Osgoode Hall Law School from 1894 to 1923. Archives of the Law Society of Upper Canada.

Date: [191-?]. Photographer: J. Kennedy. Reference code: P75. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/lsuc_archives/3721469888/. Original title: Portrait photograph of Dr. Newman Wright Hoyles (1844-1927), principal of Osgoode Hall Law School from 1894 to 1923. Archives of the Law Society of Upper Canada.

Date: [191-?]. Photographer: J. Kennedy. Reference code: P75. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/lsuc_archives/3721469888/.](/bioimages/w600.12831.jpg)

Source: Link

HOYLES, NEWMAN WRIGHT, lawyer, educator, and Anglican layman; b. 14 March 1844 in St John’s, son of Hugh William Hoyles* and Jean Liddell; m. 27 Nov. 1873 Georgina Martha Moffatt, daughter of Lewis Moffatt*, in Toronto, and they had two sons and two daughters; d. there 6 Nov. 1927.

A third-generation Newfoundlander, Newman Hoyles grew up in St John’s, the son of a leading lawyer and future premier and chief justice. In 1858 his parents sent him for schooling, not to Britain, but to Upper Canada College in Toronto. After two years there, Hoyles attended King’s College in Windsor, N.S., and Trinity College in Cambridge, England, where he took a ba in classics and won medals in rowing. Hoyles then pursued a legal career in Toronto. Articled in 1869 and called to the bar three years later, he formed a partnership with James Bethune that grew into a prominent law firm, which included Charles Moss* and William Glenholme Falconbridge*. He was named qc by the Ontario government in 1889.

In 1894 Hoyles succeeded William Albert Reeve* as head of the law school run by the Law Society of Upper Canada – Ontario’s only accredited law school – at Osgoode Hall in Toronto. Hoyles, whose partner Charles Moss had chaired the hiring committee, had been widely seen as the establishment candidate. He had declined to apply until the salary was raised by 25 per cent, to $5,000.

The school’s program of morning lectures, followed by service “under articles” in local offices, was mandatory for would-be lawyers in Ontario. Innovations at Harvard and at Dalhousie University in Halifax [see Richard Chapman Weldon], however, had begun to establish the full-time, academic llb as the standard credential for North American lawyers, so Osgoode Hall’s training was controversial. Hoyles shared the conviction of the Law Society, which controlled the call to the bar, that no university program could adequately provide the practical training lawyers needed, and that a “learned and honourable” profession had to see to the education of its own. He believed all his life that schooling in arts or classics, followed by intense professional apprenticeship, produced the best lawyers.

In the early 20th century, when advocates of university law schools often favoured them as much for their potential to exclude socially undesirable elements from the profession as for their intellectual aspirations, Osgoode Hall accepted many students who had begun legal studies simply by finding lawyers willing to instruct them. Hoyles’s opposition to academic control over legal credentials may have reflected an underlying liberalism as well as professional pride. Throughout his tenure (and until 1957), the Law Society treated university programs as worthwhile but held that they conferred no entitlement to be called to the bar. Hoyles thus rejected several overtures from the University of Toronto. Even while helping to keep Ontario universities out of professional education in law, he was a long-time member of the University of Toronto’s senate, and he received an honorary lld from Queen’s College in Kingston in 1902.

Few innovations marked Hoyles’s 29 years as principal. Though he lectured regularly, he published no legal scholarship of substance. A popular figure, nicknamed Daddy by his students, he was reported to be kindly, courteous, and helpful. It was during his tenure that Ontario’s first women lawyers, notably Clara Brett Martin, and most of its early Jewish lawyers, among them Arthur Cohen*, entered the profession. In 1923 Hoyles called the entry of women the most important change seen during his principalship, though he doubted whether they would succeed “in the highest branches of law – in pleading in court.” He retired in 1923, not quite 80 years old, and was succeeded by his deputy, the much more scholarly John Delatre Falconbridge*.

Hoyles’s other lifelong commitment was Anglican evangelicalism. In Newfoundland his family had supported evangelical causes, but friends said his faith had been sparked in 1877 by the Toronto crusade of the Irish-born evangelist William Stephen Rainsford. At the time disputes between evangelicals and Anglo-Catholics were causing near-schism in the diocese of Toronto. The lay evangelicals, low church but not low society, were led by Samuel Hume Blake* and other social and professional colleagues of Hoyles who poured their organizing skills and funds into supporting “protestant” Anglicanism.

Hoyles did mission work in his parish (St Philip’s), but his most visible contribution was service to evangelicals’ institutional network. In 1877 he helped found the Protestant Episcopal Divinity School [see James Paterson Sheraton*], the evangelical alternative to Trinity College in Toronto, where his father-in-law was a council member. Religious-oriented organizations later supported by Hoyles included Bishop Ridley College in St Catharines and Havergal Ladies’ College and the Evangelical Churchman in Toronto. He served for decades on the boards, and eventually as chairman or president, of these bodies. In 1904 he negotiated the merger of the Upper Canada Bible Society with other provincial societies to form the Canadian Bible Society, and he would serve as its national president until 1921. He was a frequent delegate to the General Synod of the Church of England in Canada, from its foundation in 1893 until 1908, and he represented the church and its missionary society at international congresses.

He and his family lived in Toronto’s Annex district, on Lowther Avenue after 1892 and later on Huron Street. His elder son, Hugh Lewis, who had attended both University College and Osgoode Hall and was called to the bar in 1906, joined the Canadian army while practising law in Montreal and was killed in action in 1918. Family tradition suggests that, at the end of his life, Newman Hoyles was somewhat estranged from his widowed daughter-in-law, who had soon remarried. But his will, signed five months before his death in 1927 at age 83, was scrupulously fair in providing for his own widow, making small bequests to friends and relatives, and dividing the rest of his $45,000 estate among his three surviving children and Hugh’s son and daughter. Obituaries of Hoyles stressed his absolute faith in the Bible and his “quiet,” “unobtrusive,” and “unswerving” service to Osgoode Hall and to the evangelical cause.

[Family traditions were kindly provided by John Hoyles of Ottawa, a great-grandson of the subject. c.m.]

AO, RG 22-305, no.58183. Law Soc. of Upper Canada Arch. (Toronto), 1-5 (Convocation, rolls), common roll, Michaelmas term, 1869; Curtis Cole, “A history of Osgoode Hall Law School, 1889–1989.” Globe, 28 Nov. 1873. Mail (Toronto), 28 Nov. 1873. Toronto Daily Star, 26 Nov. 1923. Canadian Bible Soc., Annual report (Toronto), 1928. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). The jubilee volume of Wycliffe College (Toronto, 1927). Christopher Moore, The Law Society of Upper Canada and Ontario’s lawyers, 1797–1997 (Toronto, 1997). W. W. Pue, “Common law legal education in Canada’s age of light, soap and water,” Manitoba Law Journal (Winnipeg), 23 (1995): 654–88. The roll of pupils of Upper Canada College, Toronto, January, 1830, to June, 1916, ed. A. H. Young (Kingston, Ont., 1917).

Cite This Article

Christopher Moore, “HOYLES, NEWMAN WRIGHT (1844-1927),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hoyles_newman_wright_1844_1927_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hoyles_newman_wright_1844_1927_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Christopher Moore |

| Title of Article: | HOYLES, NEWMAN WRIGHT (1844-1927) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |