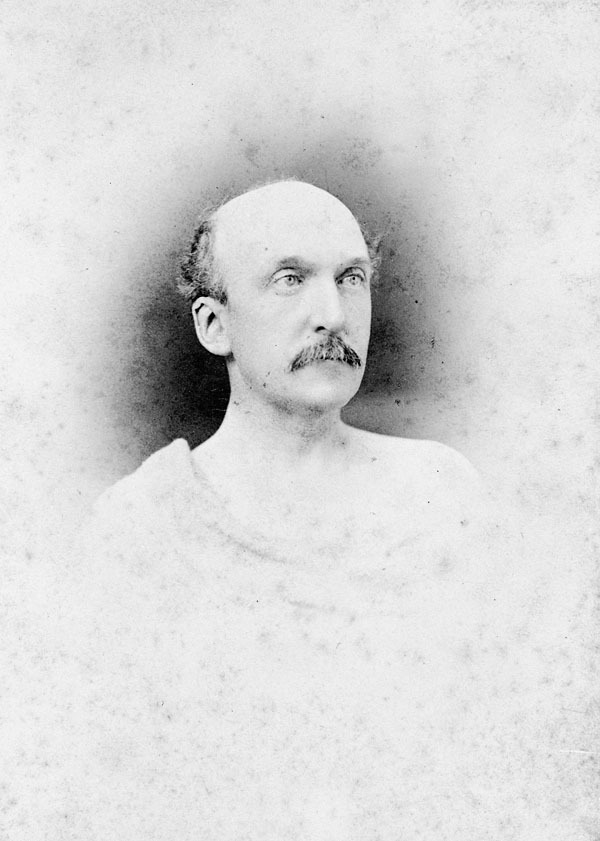

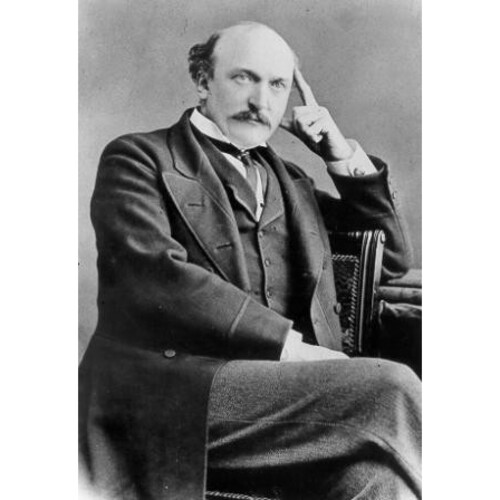

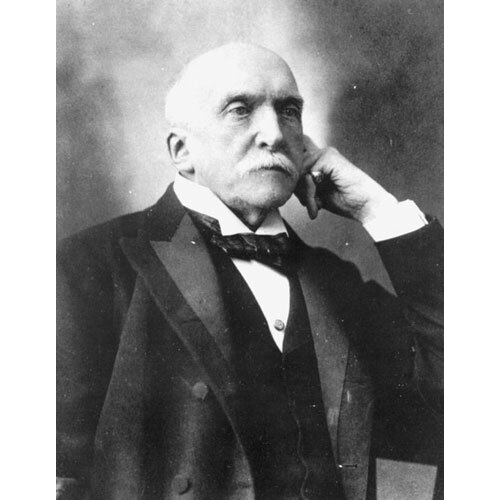

DAVIN, NICHOLAS FLOOD (baptized Nicholas Francis), journalist, lawyer, orator, politician, writer, and poet; b. 13 Jan. 1840 in Kilfinane (Republic of Ireland), eldest child of Nicholas Flood Davin and Eliza Lane; a relationship with Katherine E. Simpson* Hayes from 1886 to April 1895 produced a son and a daughter; m. 25 July 1895 Eliza Jane Reid in Ottawa; they had no children; d. 18 Oct. 1901 in Winnipeg and was buried on 22 October in Beechwood Cemetery, Ottawa.

Nicholas Flood Davin deliberately shrouded his early life in ambiguity. Virtually all that we know of him before his arrival in Canada comes from his own testimony. In addition to falsifying his middle name, the year of his birth, his father’s occupation, and his family’s Catholic religious background, Davin may have invented and certainly embellished some of the details of his Irish and English pasts. Raised after his father’s death in the house of his uncle, Protestant apothecary James Flood Davin, “Nick” was indulged by a widowed mother who, according to Kate Simpson Hayes, “lacked spanking power” and let him “jump over the traces.” His childhood ended abruptly when he was apprenticed to an ironmonger at age 18. After what Davin described as six unhappy years, his uncle allowed him to leave his master for Queen’s College, Cork. Later in life Davin demonstrated in speeches and prose the polish of a classical education, but there is no satisfactory explanation of how he acquired it. The Queen’s College register reveals that he stayed for only one term, and his claim to have studied at the University of London is unsupported by university records.

In 1865 Davin joined the Irish exodus to London in search of opportunity. He entered the Middle Temple to study law and was called to the bar on 27 Jan. 1868. Although he kept legal chambers in the Middle Temple thereafter, Davin earned his living primarily as a journalist, working as a parliamentary reporter for the London Star, as a correspondent during the Franco-German War for the Irish Times of Dublin and the London Standard, and as the editor of the Belfast Times. Davin was dismissed from the Belfast Times after five months, allegedly for “being so drunk as to be unable to write anything for the paper.” He sued for wrongful dismissal and settled out of court for six weeks’ salary. At loose ends, he received a special assignment – or so he later maintained – from the Pall Mall Gazette of London to produce a series on the possible annexation of Canada by the United States.

Davin arrived in Toronto in July 1872. A former colleague from the London Star, Alfred Hutchinson Dymond, hired him to write literary criticism for the Toronto Globe. But the real launching of Davin’s Canadian career took place on the platform of Shaftesbury Hall on 19 April 1873. Chosen by the St George’s Society in Toronto to respond to a “spread-eagle” speech on “the rise and progress of the United States” by a visiting American lecturer, Davin delivered a spellbinding denunciation of republican materialism. His paean to the more orderly society of a Canada presided over by the “faction-unsullied figure of the sovereign” was published as British versus American civilization . . . (Toronto, 1873), the second pamphlet in a series inaugurated by William Alexander Foster*’s Canada First; or, our new nationality . . . (Toronto, 1871). This was a theme to which Davin regularly returned during almost three decades as a journalist and politician.

Davin left the Globe to freelance in 1875. He contributed regularly to the Toronto Mail, and was called to the Ontario bar on 18 Feb. 1876. Although he listed his occupation in the city directory as barrister, he was more in evidence as a lecturer, author, poet, and playwright. The Earl of Beaconsfield . . . , a hagiography of Disraeli, and The fair Grit; or, the advantages of coalition . . . , a political satire, appeared in Toronto in 1876. They were followed the next year by The Irishman in Canada (London and Toronto), generally acknowledged to be his most important contribution to Canadian letters. Davin intended this compendium of Irish contributions to the development of the country to “raise the self-respect of every Irish person in Canada.” He ignored the division between Catholic and Protestant Irish [see Patrick Boyle]. This sort of distinction was irrelevant in Canada: “In such a country, it would be an extraordinary thing if the Irishman did not rise to a high level.” Davin scorned the Orange-Green division throughout his subsequent political life, in favour of a call to “Irish national sentiment” across religious lines.

A broad appeal made sense for a young Irishman ambitious to build a wide ethnic electoral base for a career as a Conservative politician. In 1876 Davin was one of the founders of the Toronto Young Men’s Liberal-Conservative Association, and in November 1877 opposition leader Sir John A. Macdonald* received a copy of The Irishman in Canada. The accompanying note announced its author’s conviction that “political distinction is the only distinction worth anything in a colony & Canada is my country and my home.” His “choice of the Conservative party,” he told Sir John, “was a deliberate act, the result of long reflection . . . I believe Conservative statesmanship is the true statesmanship for a going country.” (Something of Davin’s penchant for self-promotion is revealed by a letter a week later to Macdonald from Davin’s publisher, requesting “a few words of recommendation” to use in advertisements for the book!) If he was blessed with a nomination, Davin vowed in a subsequent letter, “defeat would to me . . . be out of the question.” When Tory organizers in Haldimand wrote to ask “if it is possible to get N. F. Davin . . . as there is a large Irish element here and the grits is stuffing them with all sorts of lies,” Davin found the fight he wanted. He set out, as he had promised, to “canvass every voter, kiss every baby, & flatter every woman in the whole division,” and in his fiery speeches urged electors to share his vision of “a great self contained nation” of “wealthy fields, the hum of teeming cities, and the mighty murmur of a free and prosperous people.” But Canada “could only be made a nation by a Protective policy,” a high National Policy tariff which would ensure that “our young men will not have to go to an uncongenial republic in search of careers.” Liberal by acclamation in 1874, Haldimand declined Davin by only 166 votes in the general election of 17 Sept. 1878.

Near-success in a strong Liberal seat and a stream of letters to Macdonald brought Davin a short-lived appointment from the new Conservative government on 28 Jan. 1879, as a one-person investigative commission on American industrial schools for native children. His report, submitted on 14 March, recommended similar experiments in Canada. While he badgered Macdonald to “do the square thing” by rewarding his political loyalty with a patronage position, Davin wrote for the Mail and conducted his legal practice with the firm of Beaty, Hamilton, and Cassels in Toronto. The high-water mark of Davin’s legal career came on 22–23 June 1880, when he defended George Bennett*, the assassin of George Brown*. The crown’s contention that Bennett had shot Brown was unassailable, but Davin presented a well-crafted defence. Brown had refused bedrest and had died of medical complications rather than from the superficial wound. Davin, with superb oratory, argued accordingly that Brown and his physicians were in part responsible for his death. His address to the jury was described by a spectator as “a matchless rhetorical endeavour” worthy of Cicero or Henry Erskine, “one of the most masterly appeals for a human life that has ever been heard in a Toronto Court-room.” George Bennett was hanged on 23 July 1880.

But despite his apparent mastery of both professions, neither journalism nor the law met Davin’s ambitions or filled his purse to his satisfaction. When he complained that “I have not been able for months to send a sixpence to my family, [and] I have been unable to keep up my subscription to the [Young Men’s Liberal-Conservative] club,” Macdonald at last found him another patronage post. Davin declined the invitation he received to Bennett’s execution and instead journeyed to Ottawa to take up his new job as secretary of the royal commission on the Canadian Pacific Railway.

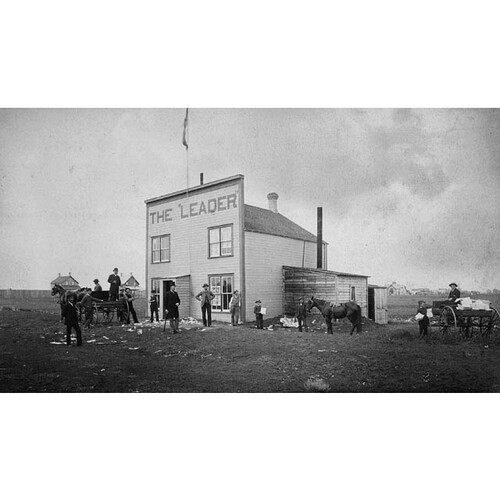

Davin’s subsequent decision to go west has been attributed by Roy St George Stubbs to “a chance visit he made to the North-West Territories, in company with a party of C.P.R. officials,” an inaccurate reference to his work with the royal commission. He had in fact nagged Macdonald for “some position in the North West” since December 1878, and his decision to move west without one seems to have been prompted by his inability to obtain a nomination for the general election of 20 June 1882. Davin’s goal was to found a Conservative newspaper in the future territorial capital of Regina, and to do so he sought a “very substantial guarantee” of financial support from the party. He justified the request to Macdonald by warning “what a wild young colt the whole North West is, and how soon it will take to plunging unless well bitted, snaffled & curbed.”

Macdonald turned to CPR president George Stephen* to provide Davin’s subsidy in the form of lots in the Regina town-site to the value of $5,000. Stephen regarded the subsidy as a good investment for the party and the railway. “Davin is all right and can do us all good service,” he agreed. “He is a good man for the West & ought to be secured in our joint interest. Regina is an important point.” Davin insisted that the lots be registered in his name before the first issue of the paper appeared, lest “they would partake of the character of a bribe.”

In his first editorial in the Regina Leader, on 1 March 1883, Davin promised that “no corporation, no party, no government, however strong, however powerful, can exact more than justice at our hands.” But he added that “less than justice neither need fear to get.” Rather than being “an impassioned voice of regional interests,” as Neil K. Besner has described it, the paper under Davin’s direction was a western mouthpiece for the CPR and the Conservative party. “The interests of the C.P.R. are bound up with the North-West,” he editorialized; “our prosperity is their’s, and their enemy is ours, and the full development of the territories means the complete realization of the hopes of the C.P.R. projectors.”

After the Leader had been a month in operation, Davin boasted to Lieutenant Governor Edgar Dewdney* that “my paper has been almost a phenomenal success. My circulation this week is 4500 & . . . from every corner of the Dominion unsolicited subscribers have poured in to my little prairie office. You can tell Sir John so long as I have a lance to break I will break it in his service.” On 16 July 1883 Davin won his first elective office, a place on the ad hoc Regina Citizens’ Committee. But within six months his Regina bubble had burst. Davin’s real estate was worth a tenth of what he had been promised, and he was begging Dewdney for government advertising to support the Leader. In February 1884 he returned to Ontario, ostensibly to lobby parliament on behalf of the northwest, but also to campaign for a post more to his taste than a frontier editor’s chair. He urged the prime minister that the position of parliamentary librarian should be “marked out specially for literary men,” in whose numbers he counted himself as “a man who for twelve years has taken so much interest in Canadian literature.” Macdonald provided Davin with something more modest and less permanent, the secretaryship of the royal commission on Chinese immigration. He did so over the objections of commissioner Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau*. “Davin,” Macdonald admitted, “has his faults, but he also has great merits. He is industrious, well read, and can sift and classify evidence.” The investigations of the commission kept Davin away from Regina until the 1885 rebellion and the trial of Louis Riel* focused national attention upon it. The Leader’s circulation soared, spurred by Davin’s dramatic execution-eve interview with Riel, an interview he obtained by disguising himself as a priest to get inside the condemned man’s cell.

After 1885 Davin made the best of Regina. The handsome bachelor, a dandy who affected a top hat and a flowing cape instead of the heavy coats and fur hats of most western men, cut a distinct figure in the muddy streets of the capital. Appointed a justice of the peace on 24 Sept. 1885, he was admitted to the bar on 11 Jan. 1886. The Leader prospered sufficiently that by 1887 Davin boasted of “a larger circulation than all the other papers of the North-West put together,” and demanded that his advertisers pay their accounts “quarterly, in advance.” He was further reconciled to Regina by a romantic attachment to Kate Simpson Hayes, a local milliner with literary ambitions who was separated from her husband. Their relationship would produce a son and a daughter, both of whom were “placed” outside the little community. He also re-entered electoral politics. He had advocated parliamentary representation for the North-West Territories since his arrival in Regina. When four constituencies were created in 1886, he won the Conservative nomination for Assiniboia West and handily carried the seat in the general election of 22 Feb. 1887 with 63 per cent of the popular vote and majorities in all but four polls.

Davin played no significant role in the second and third phases of the crusade for greater regional autonomy: the campaigns for responsible government and provincial status. Contentions by John H. Archer in Saskatchewan: a history and Lee Gibson in the Canadian encyclopedia that Davin was among the “vocal supporters of territorial self government” and that “Davin tried to gain provincial status for the territory” are incorrect. The exigencies of local electoral politics sometimes required vaguely worded pieties from him on both subjects, but he made clear to Ottawa in private that “a little temporizing” was all that was needed to “prevent the occurrence of serious difficulty.” Davin was a Canadian nationalist, who despised regionalism as a political weapon. “I do not believe in sectionalism,” he would tell Prime Minister Sir John Sparrow David Thompson* bluntly, but confidentially, in 1893. Davin was hostile to Frederick William Gordon Haultain*, leader of the Advisory Council established in 1888 and of the movement for responsible government. As long as the Conservatives held power nationally, he regarded demands from the territorial Legislative Assembly, whose members he dismissed as “a pack of fools,” as Grit plots to embarrass his party. Davin was untroubled that the territories were run from Ottawa – provided that cabinet ministers and the dominion bureaucracy respected the patronage prerogatives of the member for Assiniboia West. “If you make an appointment without my recommendation,” he thundered at Hayter Reed* of the Department of Indian Affairs, “I will not tamely submit to it.”

In parliament Davin became known better for the style than for the substance of his contributions to debate. Opposition members derided him as “the blatherskite from West Assiniboia,” and as “the incarnation of the Banff Springs, namely, gush and gas.” Henri Bourassa* called him “Almighty Voice.” But in the cut and thrust of the commons Davin gave as good or better than he got. Told by a heckler that “you make such a fool of yourself,” he riposted that “I will not go to that length in the sincerest form of flattery to the hon. gentleman.” To an opponent who lampooned his baldness Davin replied, “Though I am more bare-headed than he is, he is more bare-faced than I am.” Macdonald called on Davin’s oratorical powers when parliamentary tactics required delaying a division in the house. The list of legislation connected directly with Davin’s name, however, contains only one item: a minor 1892 amendment to the Dominion Lands Act that retroactively extended the privilege of claiming a second homestead to settlers who had arrived in the west between June 1887 and June 1889.

Davin’s historical reputation as a politician with an “inherent sense of justice and tolerance,” in the words of C. B. Koester, originates from his support of bilingualism in the west. He defended the dual-language provisions of section 110 of the North-West Territories Act against D’Alton McCarthy* in 1889–90, although his Leader editorials censured McCarthy’s “violent and offensive language” more than they vindicated French-language rights. Davin was prepared to see bilingualism abolished “if it should be decided that in any part of the Dominion the dual language is not necessary,” but he asked that “it be abolished without exciting cries or dithyrambics.” In parliament Davin proposed that the language issue be left up to a territorial assembly which he knew was predisposed toward unilingualism. His position on the schools questions in Manitoba and the North-West Territories was similarly ambiguous; he supported “one state system of education which does not insist on one form or another of dogmatic teaching,” yet insisted that “no man can be well educated who is not religiously educated.” Davin at first opposed but in the end supported his party’s proposed remedial legislation, drawing fire from both the Orange lodge and Archbishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché*. His less-than-spirited defence of French Catholics was hardly heroic, but his rejection of the divisive racial appeals so common to the period does mark him as an exception. Although he described anti-French-Catholic sentiment in the west as “perhaps stupid prejudices” and insisted that “I of course have no prejudices,” he conceded in private that “this is an English speaking &, in common parlance, an Anglo Saxon community.”

Davin has been credited by his biographers with “stray strands of liberalism” because of two intercessions he made on behalf of women’s rights well before such positions were common. In 1888 he urged Thompson, then minister of justice, that women no longer be liable to have property seized to discharge their husbands’ debts, and on 8 May 1895 he moved a woman’s suffrage bill in the commons. These isolated outbreaks of feminism can be best explained by events in his personal relationship with Kate Simpson Hayes, who had strong feminist convictions: to Davin, most things were personal, in and out of politics.

Davin’s reputation as maverick within the Conservative party does not grow out of his departures from traditional Tory ideology, but out of several public feuds based more on personality than principle. A vendetta which led him to make largely ill-founded charges against the North-West Mounted Police in 1889 dated from 24 Aug. 1884, when Davin had been arrested by Superintendent William Macauley Herchmer* for wandering drunk and half-disrobed through a first-class railway car. Better-substantiated attacks on the minister of the interior and superintendent general of Indian affairs, Edgar Dewdney, reflected Davin’s jealousy at being passed over for cabinet rank himself. There was also a degree of political calculation in his excoriations of these prominent figures of western Conservatism. Day Hort MacDowall, Conservative mp for Saskatchewan, noted to Dewdney that the charges were “of course . . . held up as a sign of Davin’s independence and how necessary it is to have representatives who will rather sacrifice their party.”

Although re-elected with an increased majority in 1891, Davin suffered a succession of bitter political disappointments thereafter. He was passed over again for cabinet. This time the Department of the Interior went to Thomas Mayne Daly*, in October 1892, and reportedly Davin “was shocked into a long drinking spree.” Determined to leave electoral politics, he desperately sought the lieutenant governorship of the territories in May and June 1893, and vociferously opposed Thompson’s eventual appointment of Charles Herbert Mackintosh*. He had not lost his touch on the hustings, however: Davin was the only one of the territories’ four Tories to be re-elected on 23 June 1896, albeit that he won by the tie-breaking vote of a returning officer he had favoured with patronage in the past. Although he had supported the official Conservative position on Manitoba schools, the CPR, and the tariff (with slight caveats on the latter) in every election in which he contested Assiniboia West, Davin polled a larger percentage of the popular vote than the Conservative party did nationally or in the territories. His electoral success was in large part personal, based on loyalties built up through a magnetic personality and the careful application of patronage.

Davin’s active legal career had effectively ended with his move to Regina. He had ceased his involvement with the day-to-day management of the Leader after his election to parliament, contributing only editorials; on 22 Aug. 1895 he sold the paper to Walter Scott*. Although his literary ambitions were undiminished, politics interfered, as it had done in the past. Davin seemed to forget what he had once told Sir John A. Macdonald: “Literary men . . . do as much good to the country as politicians.” The most sympathetic modern criticism of his self-published Eos: an epic of the dawn, and other poems (Regina, 1889) is C. B. Koester’s judgement that, although “neither original nor profound . . . it is not a casual bit of rhyme and metre,” but rises “well above the mediocre.” A novel, “Dorsal ray,” exists only in manuscript.

Davin’s political, professional, and literary disappointments paralleled increasing personal problems. He had cultivated the stereotype of the hard-drinking, loquacious, mercurial, romantic, sentimental Irishman for so long that no biographer has been able to tell, by the time he was in his fifties, where the myth ended and the real Davin began: one wonders if Davin himself faced the same dilemma. The alcoholism which dogged him throughout his life worsened as he aged; a younger contemporary remembered that “there came a time when he could not make a speech without first speeding up his mind with alcohol.” Before the election campaign of 1891 Davin pledged publicly to give up drinking. Privately, in Kate Simpson Hayes’s words, “he tried his best again and again, but he could not control himself in any way.” Davin’s relationship with Simpson Hayes ended in April 1895, when he announced that he would marry Eliza Jane Reid. Their six-year marriage appears to have been not entirely a happy one, but Davin was able to make a home for Henry Arthur Davin, his son by Simpson Hayes. Despite earnest attempts to do so, he was never able to find his daughter.

Between 1896 and 1900 Davin struggled as the lone territorial mp in the Conservative opposition. Sitting on the other side of the chamber removed whatever constraints he had felt as a government back-bencher. In the session of 1897 he rose to speak 1,023 times and filled 250 pages of the Debates. His opinions did not change, however. He remained a good friend of “that great C.P.R. corporation,” and an articulate imperialist, eager to have Canada “tender to the Imperial mother our good offices in every possible way” during the South African War. As president of the Territorial Liberal-Conservative Association, he attempted to reorganize the party after its 1896 electoral débâcle, but complained to Senator James Robert Gowan that “I am like a general without artillery fighting a thoroughly equipped army. I have no newspaper to protect my movements & shell the enemy’s batteries of falsehood.” Central Canadian Conservatives helped to finance the West, founded in Regina on 27 April 1899, but although Davin described it as “politically a success,” he admitted a year later that “it has not had enough of advertising patronage to keep its belly warm.” Davin blamed his defeat in the general election of 7 Nov. 1900 on Liberal chicanery; the wonder, however, was not that Davin lost but that the margin of his defeat (he won 48 per cent of the popular vote) was so narrow. There were almost four times as many voters in Assiniboia West as there had been in his first campaign in 1887, and Davin lacked the tools to make his personal style of politics work on this larger scale. His individual magnetism was eroded by alcohol, he had been deprived of patronage power since 1896, and his opponent was the owner-editor of the Leader.

There is no want of possible explanations for Davin’s suicide in his room in Winnipeg’s Clarendon Hotel on 18 Oct. 1901. His personal life was a shambles, the West was barely alive, and his parliamentary career was clearly over. He had made no progress on the great scholarly project he announced after his defeat, “to write a history of my time in Canada & give a full length portrait of Sir John A. Macdonald.” His melodramatic death was a microcosm of his life: his first revolver refused to fire, and he had to return it to Ashdown’s Hardware and buy a second pistol to accomplish his task.

Nicholas Flood Davin was a man of remarkable, but erratic and unfocused talents. Koester concludes that he should be remembered as “a member of Parliament in the very best traditions of the institution. . . . The real tragedy was . . . there were so few like him.” With all respect, it must be said that a House of Commons able to function with more than one Nicholas Flood Davin is difficult to imagine. But Davin’s lives offer us other insights into his times. His role as the Regina representative of the railway and the National Policy exemplifies J. M. S. Careless*’s notion that as Canada moved westward, the metropolis dominated the frontier. He is a textbook case of Carl Berger’s thesis about the intersection of imperialism with nationalism in late-19th-century English Canada. Finally, the inadequacy of Davin’s appeal beyond region and race to an overriding Canadian political nationality represents what William Lewis Morton* describes as “the failure . . . to maintain the Macdonaldian hope of a national spirit making a reserve paramountcy of the national government possible.”

[C. B. Koester’s full-length study, Mr. Davin, m.p.: a biography of Nicholas Flood Davin (Saskatoon, 1980), provides a bibliography of Davin’s publications (pp.223–25) and a listing by date of his specific contributions to the Regina Leader (pp.225–26). Davin’s most important work, The Irishman in Canada, has been reprinted (Shannon, Republic of Ire., 1969).

Davin lived with an eye to posterity’s judgement, and for this reason he carefully preserved his personal papers, but unfortunately none of this collection has survived. Presumably it was destroyed by Davin’s wife Eliza Jane Reid in an attempt to create a sanitized Davin for the historical record. The most important primary source of information is therefore the Macdonald papers (NA, MG 26, A), which contain over 400 letters by Davin, almost all of them written to Macdonald himself, and about 60 in which Davin is mentioned. There is also important material in the papers of Henry James Morgan* (NA, MG 29, D61), including Morgan’s notes for his sketches of Davin in the CPG and Canadian men and women of the time (1898), and for a full-length biography which was never written; the most useful part of the collection, however, is the series of letters written to Morgan between 1896 and 1904 by Kate Simpson Hayes under the pen-name Mary Markwell.

The C. B. Koester coll. at the Saskatchewan Arch. Board (Regina), containing Koester’s notes for his biography of Davin and private family papers, is closed during Koester’s lifetime. The Regina office of the Saskatchewan Arch. Board also holds several manuscripts by Davin, including that of the novel “Dorsal ray,” in the Saskatchewan Hist. Soc. colt. (SHS 14), as well as the papers of his daughter, Agnes Agatha Robinson (R–432), which document her efforts to prove her parentage. j.h.t]

NA, MG 26, D; MG 27, I, C4, 2 (mfm. at GA); E17; E106. Regina Leader, 1883–96. J. H. Archer, Saskatchewan: a history (Saskatoon, 1980). N. K. Besner, “Nicholas Flood Davin,” Dictionary of literary biography (112v. to date, Detroit, 1978– ), vol.99 (Canadian writers before 1890, ed. W. H. New, 1990): 87–91. Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1887–1900. Canadian encyclopedia. C. B. Koester, “Nicholas Flood Davin: politician-poet of the prairies,” Dalhousie Rev., 44 (1964–65): 64–74. W. L. Morton, “Confederation, 1870–1896: the end of the Macdonaldian constitution and the return to duality,” JCS, 1 (1966), no.1: 11–24. R. St G. Stubbs, Lawyers and laymen of western Canada (Toronto, 1939), 1–21. Thomas, Struggle for responsible government in N.W.T (1978). Norman Ward, “Davin and the founding of the Leader,” Sask. Hist., 6 (1953): 13–16.

Cite This Article

John Herd Thompson, “DAVIN, NICHOLAS FLOOD (baptized Nicholas Francis),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 10, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/davin_nicholas_flood_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/davin_nicholas_flood_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | John Herd Thompson |

| Title of Article: | DAVIN, NICHOLAS FLOOD (baptized Nicholas Francis) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | April 10, 2025 |