As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

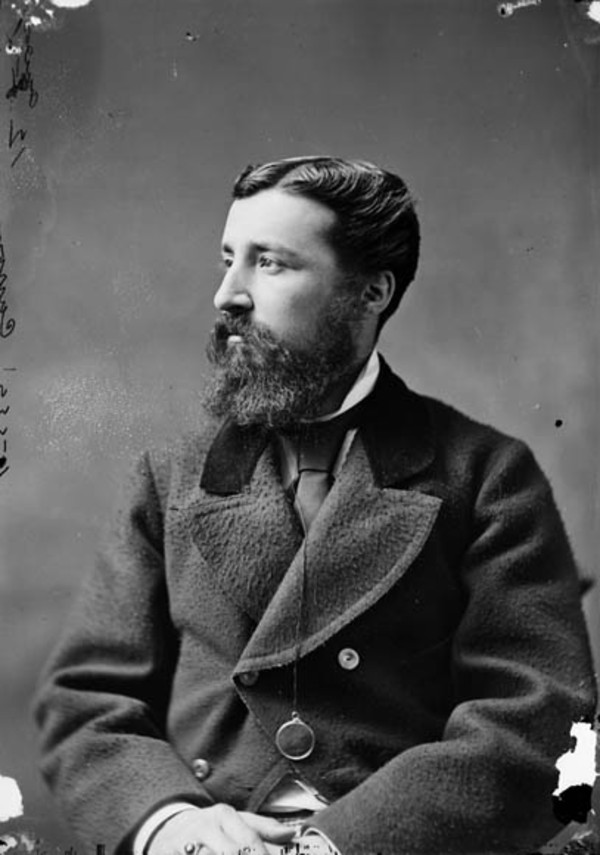

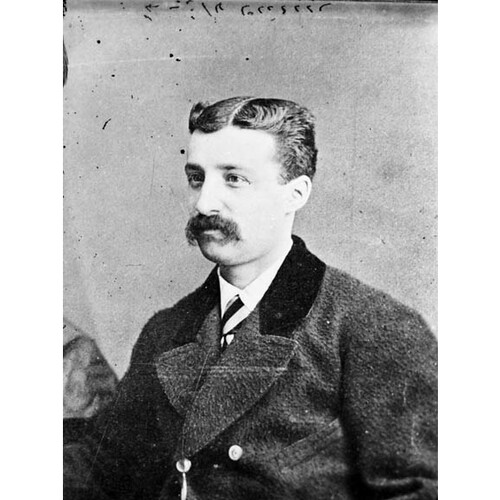

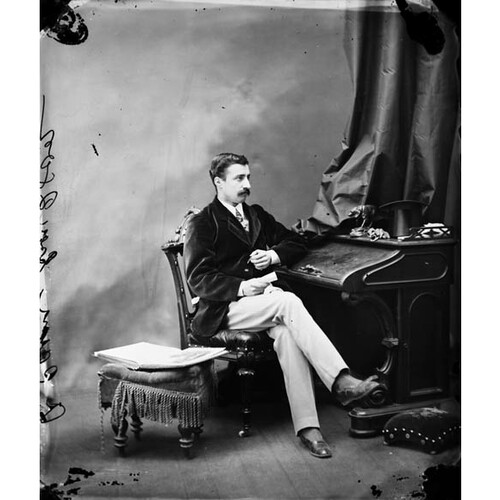

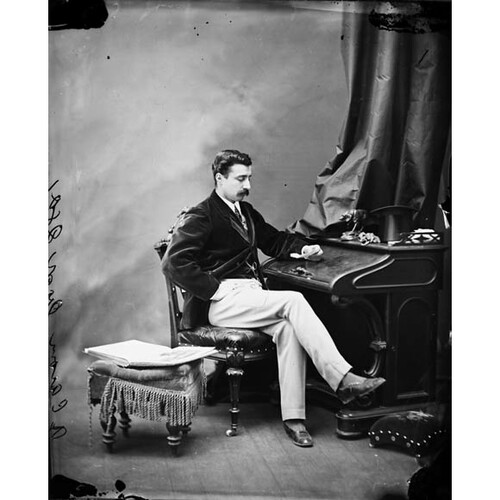

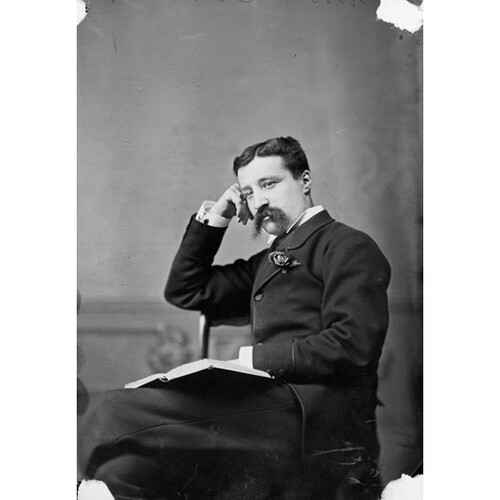

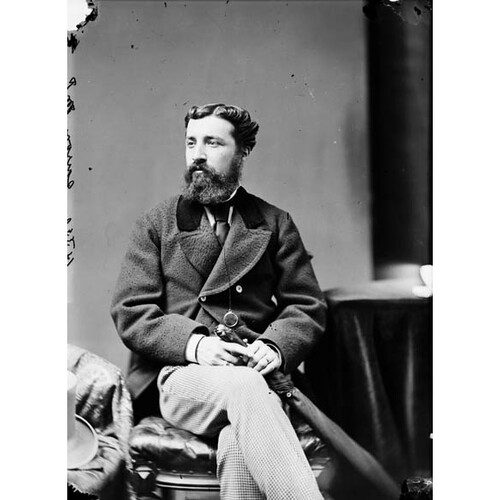

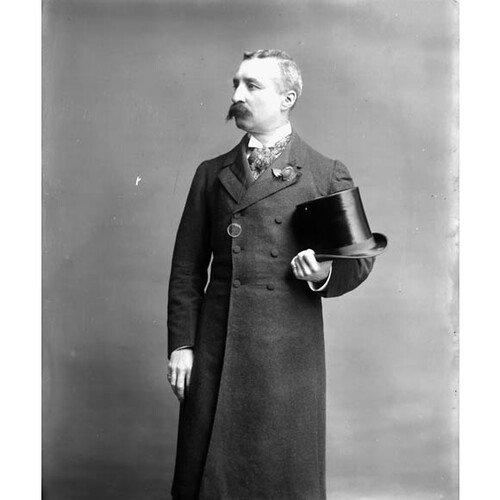

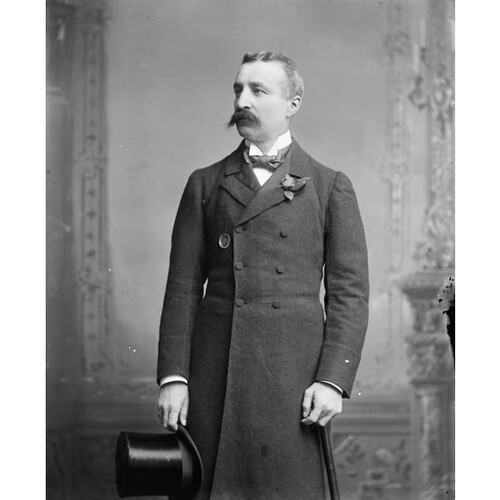

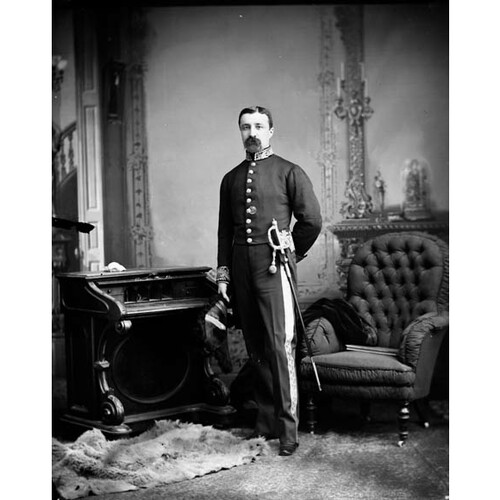

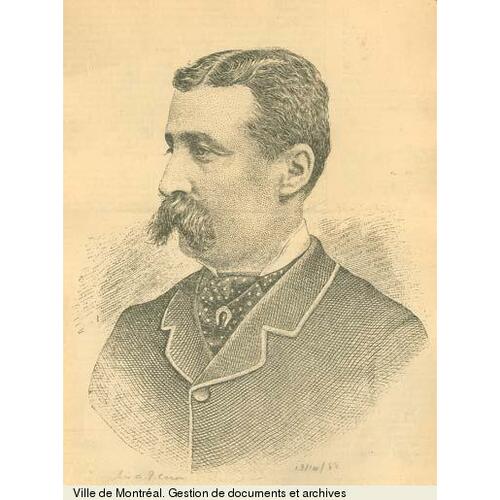

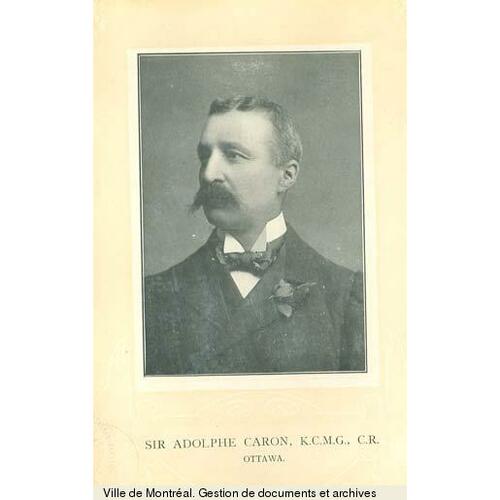

CARON, Sir ADOLPHE-PHILIPPE, lawyer and politician; b. 24 Dec. 1843 at Quebec, son of René-Édouard Caron* and Marie-Vénérande-Joséphine Deblois; m. there 25 June 1867 Alice Baby, and two of their children survived him; d. 20 April 1908 in Montreal.

Adolphe-Philippe Caron was the only surviving son of a middle-class Quebec family. After his early education at the Petit Séminaire de Québec he began the study of law, which he completed at McGill College in 1865. He already spoke and wrote English fluently, as well as French. That year he was called to the bar and joined the law firm of Frederick Americus Andrews and his son Frederick William at Quebec. He became a partner and the firm changed its name to Andrews, Caron, and Andrews.

In the federal election held in the summer of 1872, Caron ran as a Conservative in Bellechasse but was defeated by Télesphore Fournier*. In March the next year he was returned for Quebec in a by-election after Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau* obtained the speakership of the Senate. Caron would hold this seat until 1891. On 5 Nov. 1873 the government of Sir John A. Macdonald* resigned, and in the election of January 1874, the Conservatives were relegated to the opposition. At this time Hector-Louis Langevin was trying to establish his role as leader of the Conservative members of parliament from Quebec. Caron was one of the ambitious young men eager to wrest from Langevin’s hands the sceptre passed on by George-Étienne Cartier*, but he would never prove equal to the task.

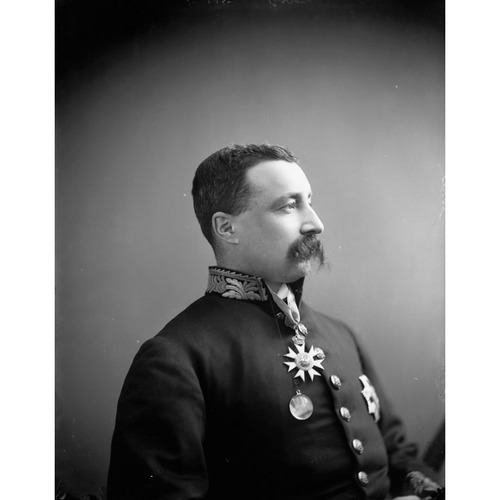

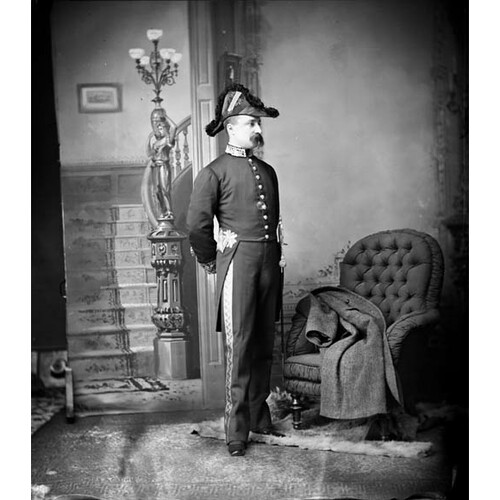

Caron was re-elected in the Conservative victory of September 1878. Despite his efforts to obtain the portfolio which fell to the Quebec region, it went to the veteran Langevin, who returned to the cabinet and continued as Macdonald’s lieutenant. Nevertheless, Caron was cabinet material. For two years he waited, all the while making his presence increasingly felt. It was he, for example, who answered opposition questions about the militia and defence during periods when the minister, Louis-Rodrigue Masson, was absent because of illness. Sir Alexander Campbell* replaced Masson for a few months in 1880, and then in November Caron became minister. For more than 11 years he would head the Department of Militia and Defence.

Not yet 37, Caron was the youngest minister in Macdonald’s cabinet, and he already had seven years of parliamentary experience. Whatever hopes he may have had of replacing Langevin were thwarted, however, by the appointment of another contender, Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau*, to the cabinet in July 1882. Aware of Caron’s aspirations, Langevin is believed to have wanted him removed from the government and replaced by Chapleau, but Caron succeeded in retaining office.

Caron made his chief contribution to the political life of the country as minister of militia and defence. Almost as soon as he was appointed, he came into conflict with Richard George Amherst Luard*, the British general commanding the Canadian militia. Unlike his father and many colleagues on both sides of the house, Caron had never served in the militia. However, Canada was passing – albeit timidly – through a phase of national self-assertion, and Canadian militiamen, whether English- or French-speaking, had scant affection for the British regulars who came to lecture them on professionalism. The confrontation between Luard and Caron stemmed from two different points of view: the imperialist concept, coming from London, of what the Canadian militia ought to be, and the attitude of Canadian politicians, too often satisfied to have officers appointed on the basis of political friendship rather than competence and unconcerned with building an effective army. Caron was not in the least disconcerted by Luard, who relied for support on the governor general, the Marquess of Lorne [Campbell*]. He handled himself well in his dealings with a general who not only lacked tact, but knew so little French that he returned documents written in that language, to have them translated. By taking a firm stand, the minister helped get London to take local factors into account when appointing general officers for Canada.

It often happened, however, that Canadian nationalism and the recommendations of British generals were in accord. For instance, under Caron a cartridge factory was built at Quebec in 1882 [see Oscar Prévost*]. Although the project had been started before his time, its completion added to the list of local products manufactured for the militia, and fitted in admirably with the Macdonald government’s National Policy. It was also during Caron’s tenure that professionalism in the Canadian defence forces was advanced by the creation, in 1883, of three infantry schools and the addition of an artillery battery to the two already in existence. But these developments did not proceed without criticism. There was talk of political patronage because the cartridge factory was located in Quebec City. As well, the militia officers sitting in parliament were wary of the increase in the regular forces that resulted from the new schools, for it meant that there was less money for the amateur soldiers under their command. Indeed, the regular force of 750 was allocated the same amount as the 20,000-man militia. In 1883 Caron repeated his assurances to parliament that the schools did not herald a huge professional army. His caution towards professionalizing and “Canadianizing” the armed forces served only to delay the inevitable, however.

Budget allocations increased during Caron’s term of office (even discounting the North-West campaign of 1885), but there were so many high-priority questions that they could not all be dealt with. Although the number of professional soldiers was increasing, funding for the militia had to be capped and, indeed, reduced. Plans for construction or renovation were set aside; the regulars remained quite badly paid and had no assured income when they retired. Although the minister took his role seriously (as some of the militiamen in the opposition were prepared to concede), undoubtedly political considerations too often took precedence. To Caron, the support of the thousands in the militia seemed more important than that of the hundreds of professional soldiers whom he had deliberately dispersed throughout Canada so as to dispel fears that a huge career army would take over the militia’s duties. Members of parliament who were also officers could thus feel that they had some protection from the arrogance of the regular officers who might make them lose standing in the eyes of the militiamen among their constituents.

The North-West campaign in the spring of 1885 [see Sir Frederick Dobson Middleton*; Louis Riel*] gave Caron the chance to demonstrate once more the dynamic energy revealed in his previous actions. In sending nearly 8,000 men more than 1,800 miles from their main supply centres, the minister had to show boldness and initiative. He organized the call-up and dispatch of units, as well as their logistical support, in masterly fashion under particularly difficult conditions. The ill-prepared and inexperienced militia acquitted itself very well, thereby jeopardizing future allocations for the regular troops. Ingenuity made up for inexperience. A field ambulance service was improvised, and the cooperation of the Hudson’s Bay Company, which helped furnish supplies, and the Canadian Pacific Railway Company, which facilitated transportation, proved vital to the success of the undertaking. Caron urged two French Canadian regiments to take the field and demonstrate the loyalty of Quebec in this kind of crisis. One of them, the 9th Battalion Volunteer Militia Rifles, was under the command of Guillaume Amyot*, the mp for Bellechasse.

Although the military campaign was conducted effectively, in the aftermath there were countless recriminations. Needless to say, the division between the militia and the regular army intensified. Some of Caron’s colleagues resented that he had been made a kcmg on 25 Aug. 1885 when he had made little effort to obtain decorations for those who had risked their lives in combat. In fact, Caron’s name had been proposed by the colonial secretary against the advice of Macdonald, who had argued that his minister at 41 was too young. As for the mps in the militia, all they got from the house was a motion of congratulations and thanks. Even the 1886 official report of the operation scarcely mentioned them.

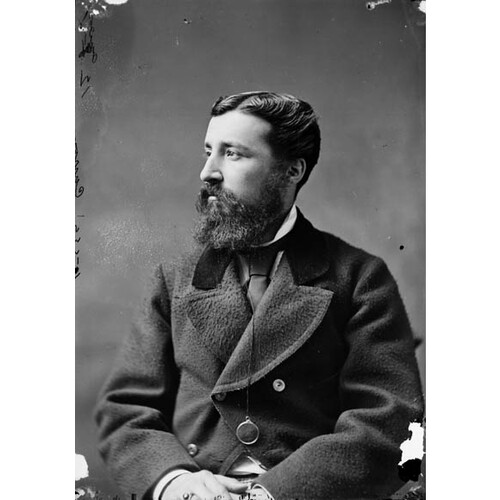

In November 1885 Caron was in Winnipeg settling the final administrative details related to the campaign. He was invited to a banquet on the day set for Riel’s execution and, in accepting, he became a prime target for French-speaking Canadians who resented the Conservative government’s decision to carry out the sentence. In fact, the execution was postponed until 16 November, in Regina, as Caron had known when he left Ottawa that it would be. None the less, he was accused of being willing to carouse under Riel’s scaffold. In March 1886 he defended himself in the house against all the accusations levelled at him. By maintaining cabinet solidarity, he said, he had done nothing but uphold law and order. No doubt in standing firm against all opposition, he and his French-speaking colleagues Langevin and Chapleau helped prevent the country from being split along linguistic lines. He would not be the only French Canadian, then or later, who chose to yield rather than resign. But he was in a wrenching situation. Perhaps Caron defended himself too well. In politics, the accused often try at all costs to prove their innocence instead of putting the burden of proof on their accusers as the courts would do. In the case of the Winnipeg banquet, Caron can be said to have shown some lack of discernment.

In the general election of 1887 the Conservatives again won a majority in the province of Quebec, but they lost much of their support, especially in the Quebec City district, for which Caron was responsible. His political courage and that of his French-speaking friends was not enough to deflect the surge of discontent aroused by Riel’s execution. Not everyone believed them when they said that this deed was attributable to Protestant fanaticism. Then there was a resurgence of all the frustrated complaints of the militiamen in politics. Some came from former political friends such as Amyot, who accused Caron of every conceivable wrongdoing: losing the Quebec district to the Liberals, putting Honoré Mercier* in the provincial legislature, and dealing unfairly with Amyot himself by failing to pay some of the campaign expenses of his battalion because he reportedly had had the audacity to defend the cause of the French Canadians and Riel to the very end.

Caron’s downhill slide continued, especially in some English-language newspapers which accused him of favouring Quebec and demanded his replacement by an anglophone. In coming to his defence, Macdonald probably gave him false hopes of being able to supplant Langevin, whose integrity was under heavy attack in 1890. Some parts of the material that Langevin’s political enemies had in their hands may well have come from Caron. Although Langevin and Caron were rivals for the leadership of the federal Conservative party in Quebec, on the Manitoba school question [see Alexandre-Antonin Taché*] they were allies. This long six-year struggle, which began in 1890, would come to an end under Wilfrid Laurier*, and the French-speaking Manitobans were to be the losers. Caron and the French Canadian Conservatives, by defending the cause of the Catholic schools in that part of the country, would share responsibility for the Conservatives’ loss to the Liberals in 1896.

With Macdonald’s death on 6 June 1891, Caron lost an important bulwark. In January 1892 he was shifted against his will to the office of postmaster general. More attacks on his political integrity were made although, given the prevailing standards of conduct in politics, they were not well founded. At the same time the influence of the French-speaking Conservatives from Quebec was declining within the party. In the March 1891 election the Liberals for the first time since 1878 had won more seats in the province than the Conservatives. Caron himself was elected in Rimouski, the riding he would represent until 1896.

Although Caron did not dispense patronage on the same scale as Langevin, his actions were sufficiently notorious that the Liberals mentioned him by name in their documents. In 1892 there was an attempt to discredit him in connection with a scandal [see Sir James David Edgar*], although it was Langevin who was behind the affair. In 1895 he was implicated in another alleged case of election corruption, for which there was, in fact, no basis. None the less, this new accusation, combined with his firm stand on the Manitoba school question, proved his undoing. He was exerting every effort to get the government to pass remedial legislation that would restore the Catholic schools in Manitoba. The bill led to the fall of the Conservatives, but Caron’s own downfall came even earlier, for he was not included in the last Conservative cabinet of May–July 1896 under Sir Charles Tupper*. With the government’s defeat he returned to the opposition benches, where he sat for Trois-Rivières until 9 Oct. 1900. In November of that year he ran in Maskmongé and was defeated.

The last eight years of his life saw Caron go back to his roots. He had been made a qc in 1879 and now devoted himself to the practice of law and to a business that proved fairly prosperous. In private he was a man who loved life. Priding himself on his refinement, he occasionally gave receptions at which music and poetry were featured. After an illness of several months, he died rather suddenly in Montreal on 20 April 1908. He was buried in the cemetery of Notre-Dame de Belmont in Sainte-Foy, near Quebec.

[Sir Adolphe-Philippe Caron’s papers are held at NA, MG 27, I, D3. An excellent finding aid was prepared in 1977 by Diane Tardif-Côté. The gift of Lady Caron in 1908, the papers consist of letters, telegrams, press clippings, memoranda, notes and reports, speeches, and personal documents; the correspondence on the North-West rebellion is particularly interesting. Caron’s marriage and death certificates are at ANQ-Q, CE1-1, 25 juin 1867 and 23 avril 1908.

The brief entries on Caron in encyclopedias and biographical works often contain errors. The House of Commons Debates for 1873 to 1900, when Caron was a member, and newspapers such as La Presse, La Minerve, and Le Courrier du Canada provide information on some of the events of importance in Caron’s political career. Volume 3 of History of the federal electoral ridings, 1867–1980 (4v., [Ottawa, 1982?]) and the reports on general elections prepared for the House of Commons and found in the Sessional papers are useful reference materials.

Caron is mentioned in a great many studies. For a better understanding of his role as minister of militia and defence, see Desmond Morton, Ministers and generals: politics and the Canadian militia, 1868–1904 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1970), and S. J. Harris, Canadian brass: the making of a professional army, 1860–1939 (Toronto, 1988), although these works express some reservations that are not well founded. Désilets, Hector-Louis Langevin, places Caron in the context of the Conservative party of his day. s.b. and p.d.-b.]

Cite This Article

Serge Bernier and Pauline Dumont-Bayliss, “CARON, Sir ADOLPHE-PHILIPPE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/caron_adolphe_philippe_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/caron_adolphe_philippe_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Serge Bernier and Pauline Dumont-Bayliss |

| Title of Article: | CARON, Sir ADOLPHE-PHILIPPE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | March 29, 2025 |