Source: Link

MASKEPETOON (Broken Arm, Crooked Arm, baptized Abraham), Cree Indian chief; b. probably in 1807 in the Saskatchewan River area; d. 1869 at a Blackfoot camp in central Alberta.

Maskepetoon was the leader of a small Plains Cree band which normally hunted south of Fort Edmonton, but at times ranged into what is now southern Saskatchewan and northern Montana. Early in life he gained a reputation as a warrior and was given the name Mon-e-guh-ba-now or Mani-kap-ina, Young Man Chief, by the enemy Blackfoot. According to a Methodist missionary, Egerton Ryerson Young*, Maskepetoon “was a magnificent looking man physically, and was keen and intelligent,” although John Palliser*, in the journal of his 1857 expedition, considers him neither imposing nor fine-looking. Maskepetoon had a violent temper and as a young man was said to have scalped his wife Susewisk alive. He almost killed a Métis during a drinking bout near Fort Edmonton.

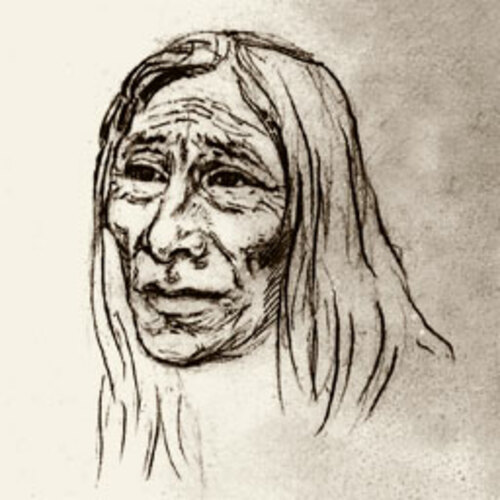

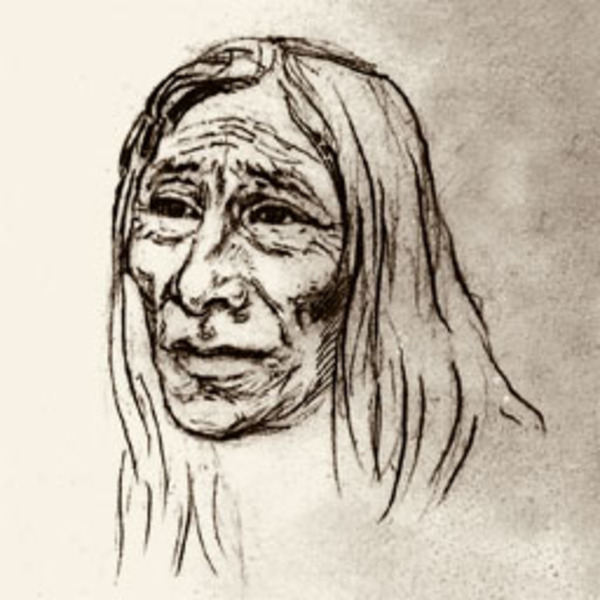

Late in 1831, while on a trading expedition to Fort Union on the Missouri River, Maskepetoon was invited to accompany three other chiefs, from the Assiniboin, Saulteaux, and Sioux tribes, to Washington, D.C., to meet President Andrew Jackson who wanted to establish peaceful relations with the western tribes and also to impress them with the might of his government. While in St Louis en route east, Maskepetoon was painted by the celebrated artist George Catlin. Upon his return to the west, Maskepetoon encountered at Fort Union in 1833 Swiss Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied, who noted that “The chief of the Crees . . . Maschkepiton (the broken arm) . . . had a medal with the effigy of the President hung round his neck.” In January 1848, the artist Paul Kane* met Maskepetoon near Fort Edmonton and recorded the chief’s views on the failure of Christian missionaries to agree with each other and on the superiority of native beliefs.

During the 1840s, Maskepetoon had come under the influence of a Wesleyan Methodist missionary, the Reverend Robert Terrill Rundle*, and later was taught to read and write Cree syllabics by the Reverend Thomas Woolsey. As a result of these associations, Maskepetoon became a strong proponent of peace. Whenever the opportunity arose, he made peace with enemy tribes and attempted to keep his young men from going to war. In these years Maskepetoon’s father was killed by a Blackfoot; when the Cree chief later met the killer on one of his missions, he invited the man into his lodge, forgave him, and presented him with a chief’s costume. In April 1865 Woolsey baptized Maskepetoon under the name Abraham, with his wife receiving the name Sarah.

In 1841 Maskepetoon had been engaged by James Sinclair* of the Hudson’s Bay Company to guide a party of emigrants from Fort Edmonton to the Oregon country. He took them along a previously unexplored route over what was later named Sinclair Pass and on to Fort Vancouver (Vancouver, Wash.). There he travelled on the HBC ship Beaver (1841), and claimed he would not be able to tell his people as they would not believe that a large ship could move on the ocean under its own power. Maskepetoon made further trips across the mountains in 1850 and 1854, on these occasions guiding Sinclair only as far as the west slope of the Rockies. In 1857 he was engaged by John Palliser’s expedition to act as guide from the Qu’Appelle lakes (near Fort Qu’Appelle) to the elbow of the South Saskatchewan River (near Elbow); from the expedition’s members he acquired the name Nichiwa, the Cree term for “friend.”

In 1869, when hostilities broke out between the Crees and the Blood, Blackfoot, and Peigan tribes, Maskepetoon entered a Blackfoot camp alone and unarmed to negotiate peace. He was met and killed by a war chief, Big Swan. The dead chief became known to the Methodists as a “martyr of peace” and was held up as an example of a man dying for his Christian faith. Some Crees, however, believed his actions were not those of a peacemaker, but of a warrior who demonstrated his bravery and scorn by entering an enemy camp unarmed.

Maskepetoon has been a hero in a variety of writings. In 1957 Maskepetoon Park, a wildlife sanctuary near Red Deer, Alta, was dedicated to the memory of the Indian peacemaker.

Glenbow-Alberta Institute Archives (Calgary), Reverend John McDougall papers, file A/M 137B/f.58; Reverend Robert Terrill Rundle papers, file A/R941. Early western travels, 1748–1846; a series of annotated reprints of some of the best and rarest contemporary volumes of travel . . . , ed. R. G. Thwaites, (32v., Cleveland, Ohio, 1904–7), XXIII, 13. [Charles Larpenteur], Forty years a fur trader on the Upper Missouri; the personal narrative of Charles Larpenteur, 1833–1872, ed. Elliot Coues (Chicago, 1933), 160. Papers of Palliser expedition (Spry), 138–40, 143–44, 602. Paul Kane’s frontier; including “Wanderings of an artist among the Indians of North America,” by Paul Kane, ed. J. R. Harper (Toronto, 1971), 142. George Simpson, Narrative of a journey round the world, during the years 1841 and 1842 (2v., London, 1847), I, 241–42. J. P. Berry, Maskepetoon, Alberta’s first martyr to peace (Toronto, [1945]). D. G. Lent, West of the mountains: James Sinclair and the Hudson’s Bay Company (Seattle, Wash., 1963), 132–53, 246–61. J. [C.] McDougall, Saddle, sled and snowshoe; pioneering on the Saskatchewan in the sixties (Toronto, 1896), 197. John Maclean, Vanguards of Canada (Toronto, 1918). E. R. Young, The apostle of the north, Rev. James Evans (New York and Toronto, 1899), 139. J. E. Ewers, “When the light shone in Washington,” Montana; the Magazine of Western History (Helena), 6 (1956), 2–11. Allen Ronaghan, “The problem of Maskipiton,” Alberta History (Calgary), 24 (spring 1976), 14–19.

Cite This Article

Hugh A. Dempsey, “MASKEPETOON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/maskepetoon_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/maskepetoon_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Hugh A. Dempsey |

| Title of Article: | MASKEPETOON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1976 |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |