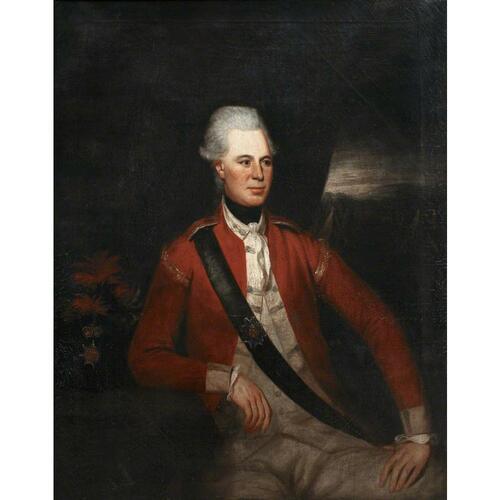

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

MACARMICK (MacCormick, Macormick), WILLIAM, colonial administrator; baptized 15 Sept. 1742 in Truro, England, son of James Macarmick, mayor of Truro in 1757 and 1766, and Philippa –; m. Catherine Buller, and they had two daughters; d. 20 Aug. 1815 in West Looe, England.

William Macarmick succeeded his father as a Truro wine merchant, and like him he was elected mayor, in 1770. He began a military career on 16 May 1759 as a lieutenant in the 75th Foot, and by 23 March 1764 he had become a captain in the 45th Foot; four years later, however, he exchanged onto half pay. During the American revolution he raised a regiment, the 93rd Foot, at his own expense, and was appointed its colonel on 2 Feb. 1780. He entered political life in 1784, allying himself with Lord Falmouth (son of Edward Boscawen*) and the tories to represent the borough of Truro in the House of Commons until February 1787. At that time he resigned to become lieutenant governor of Cape Breton Island, replacing Joseph Frederick Wallet DesBarres*. Macarmick was interested in the position because of its salary of £500 per annum and £300 in perquisites yearly out of the growing sales of coal from the Sydney mines. The appointment was due to the patronage of Falmouth, who replaced him in the Truro seat, and to Macarmick’s military services during the revolution.

Before his departure for Cape Breton, Macarmick was instructed by the British government to end the factionalism in the colony, and he arrived in Sydney on 10 Oct. 1787 determined to assert his authority and end the quarrels that had plagued DesBarres. The latter had succeeded in alienating some of the most powerful officials in Sydney, particularly the loyalists David Mathews* and Abraham Cornelius Cuyler. DesBarres’s alliance with their opponents on the council, led by Chief Justice Richard Gibbons*, had caused a rift which had eventually led to the lieutenant governor’s recall. Macarmick attempted to reconcile the two groups. But Gibbons, in an attempt to increase his power, soon organized the Friendly Society, a group formed from volunteer militia, which Macarmick outlawed when he came to fear that it might dominate him. After other incidents, he dismissed Gibbons from his posts in 1788. This action only emboldened Cuyler, who openly disagreed with Macarmick’s policies, and in 1789 he too was dismissed from the council. Five years later Mathews formed an ostensibly counter-revolutionary society, but Macarmick claimed it would “include all the principle people, [so] that I might be obliged to fill vacancies out of [it],” and managed to ban it, thus alienating Mathews. The Duke of Portland, the Home secretary, complained to Macarmick that the squabbling was hurting the colony and threatened wholesale dismissals unless it ended. This rebuke brought peace during the last six months of Macarmick’s tenure.

Macarmick took the greatest interest in the military aspects of his office. Though relations between Britain and France worsened during his period on Cape Breton, and he was ordered to maintain a state of military preparedness, he was unable to obtain arms and ammunition until 1790. Moreover, when the French revolution broke out in 1789, the garrison of the 42nd Foot was withdrawn to Halifax, leaving only a subaltern and 20 men of the 21st Foot in Sydney. Even these were withdrawn in 1793. Macarmick thus decided on his own measures. Fearing that the Acadians living around Isle Madame might assist in a French attempt to regain Cape Breton, in 1794 he strengthened a small fort near St Peters and manned it with Jerseymen and loyalists. His most ambitious plan, however, was for the formation of a colonial militia the same year. The council, led by Mathews, opposed this measure, claiming that a militia at the call of the lieutenant governor would increase his power in the absence of a house of assembly. They insisted that the militia be summoned only in extreme emergencies and with the council’s consent. Macarmick refused these terms and did not organize the militia.

The most serious encumbrance to the colony’s growth during Macarmick’s administration was the British government’s decision in 1789 to ban land grants in the Maritime provinces in order to raise money from the sale of land, a state of affairs which lasted until 1817 in Cape Breton. Macarmick tried to lessen the effects of the ban by recognizing squatters’ rights and by extending the deadline for filing land claims until 1 June 1792 for those living distant from Sydney, in which measures the British government acquiesced. Though expressly forbidden to grant land to former French citizens, Macarmick allowed a group of refugee Acadians from Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, where they had mainly worked in the fishery, to settle in the early 1790s at Isle Madame and Chéticamp. There they contributed to the island’s fishery and shipbuilding. In order to foster further settlement, Macarmick also authorized the first surveys of the area from Chéticamp to Justaucorps (Port Hood), and of the Judique and Ship Harbour (Port Hawkesbury) regions. Despite his efforts, however, the increase in population during his period of office was probably slight.

At the time of Macarmick’s arrival in Cape Breton, Britain showed only slight interest in the Sydney coal mines. By 1790, however, the stripping of timber from the coast of Nova Scotia had increased its cost, and coal consequently became more important for heating garrison barracks and for domestic use. The mines had been privately operated under a lease from the British government by Thomas Moxley, who died in 1792, and that year Macarmick transferred the lease to Jonathan Tremaine and Richard Stout. Their inefficient mining methods caused production to slump but Macarmick allowed them to continue their operation in the hope that they would pursue increased sales.

In 1794 Macarmick’s perquisites from the coal sales were discontinued. When he found out, he was bitter and immediately requested leave. He set sail from Cape Breton on 27 May 1795 but retained his position of lieutenant governor until his death. Although still on half pay, he continued to be promoted in the army, being appointed lieutenant-general on 25 Sept. 1803 and finally general on 4 June 1813.

Despite factional aggravations and an impossible political and military situation, William Macarmick revealed a patient and reasonable disposition while in Cape Breton. Though the colony failed to grow during his tenure, his liberal land policies and tolerant attitude towards the Acadians contributed to Cape Breton’s later development.

PAC, MG 11, [CO 217] Nova Scotia A, 4: 109–10, 163–65, 187; 5: 84; 6: 32–33; 7: 2–3, 7–11, 123, 125–26; 10: 80–84, 125–33, 177–79; 11: 89–90; 12: 52–53, 73–75, 276–77; [CO 220] Nova Scotia B, 3: 116–19, 125–26; 5: 44–45; 7: 97–98, 127–34; 8: 16–19, 52–57, 84–103. PRO, CO 217/119: f.190; 217/125: f.163. L. [B.] Namier and John Brooke, The House of Commons, 1754–1790 (3v., London, 1964), 3: 78. The royal military calendar, containing the service of every general officer in the British army, from the date of their first commission . . . (3v., London, 1815–[16]), 1: 101. Morgan, “Orphan outpost.”

Cite This Article

R. J. Morgan, “MACARMICK (MacCormick, Macormick), WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macarmick_william_5E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macarmick_william_5E.html |

| Author of Article: | R. J. Morgan |

| Title of Article: | MACARMICK (MacCormick, Macormick), WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1983 |

| Access Date: | April 25, 2025 |