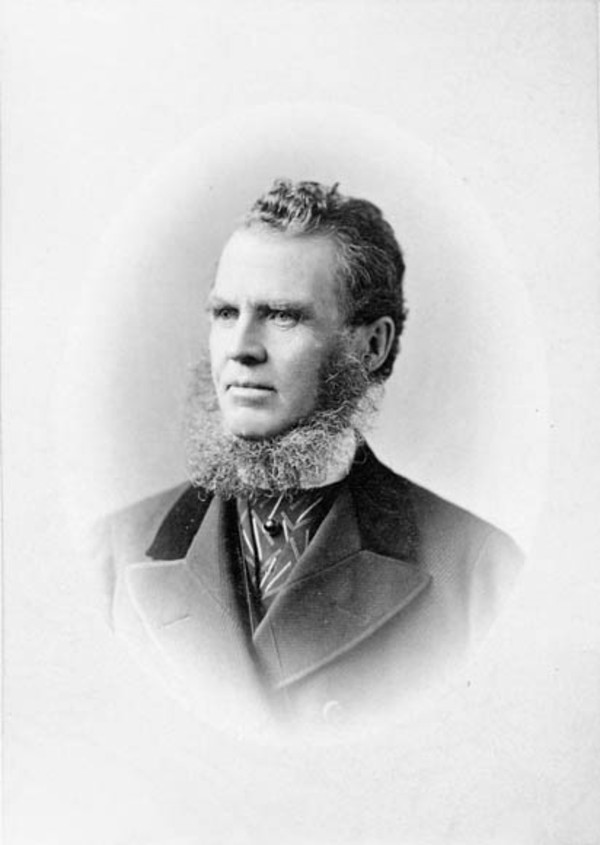

HOWLAND, Sir WILLIAM PEARCE, businessman, politician, and office holder; b. 29 May 1811 in Pawling, N.Y., son of Jonathan Howland and Lydia Pearce; m. first 12 July 1843 in Lambton Mills (Etobicoke), Upper Canada, Marianne (Mary Anne) Blyth (Blythe) (d. 1860), widow of David Webb, and they had a daughter and two sons, including William Holmes*; m. secondly 21 Nov. 1865 Susanna Julia Shrewsbury (d. 1886), widow of Philip Hunt; m. thirdly 15 Aug. 1895 Elizabeth Mary Rattray, widow of James Bethune, in Toronto; d. there 1 Jan. 1907.

A descendant of Henry Howland, a Quaker who had come to New England in 1621, William Pearce Howland received his education at Kinderhook Academy, in Kinderhook, N.Y. Subsequently he resided on Carleton Island, in the St Lawrence River, where his father had commercial interests. In 1830 he immigrated to Upper Canada. At Cooksville (Mississauga) he joined his brother Peleg in the general store of a Mr Lewis. William clerked and sorted mail, and later the two brothers purchased the store.

Between 1840 and 1857, through the rental and purchase of properties on the Humber River, Howland developed a sawmill and flour-mill complex, named Lambton Mills about 1844. By 1851 he had expanded into Toronto, where he established the Lambton Mills Depository, a wholesale warehouse for farm produce and flour. In 1855 he took Peleg into partnership. After their brother Frederick Aiken joined the firm, the Howlands expanded and prospered as owners of several stores and lumbering, rafting, and potash-manufacturing operations, as well as other resource industries, in the townships of Toronto and Chinguacousy; in the village of Kleinburg, another brother, Henry Stark, had taken over a store and milling business. By the late 1850s William was one of the wealthiest millers in Upper Canada.

Perhaps because of his American and Quaker roots, Howland had sympathized with the rebellion of 1837–38 but, because he was not yet a British citizen, he decided against joining it. Shortly after the union of the Canadas in 1841, he took out citizenship papers and became active in politics. In the election of December 1847 he supported James Hervey Price*, the reform incumbent in 1st York. By 1849 Howland had achieved such prominence among the reformers that he was chosen, along with George Brown* and Connell James Baldwin*, to present an address of support to Governor Lord Elgin [Bruce*] in Montreal immediately after the riots protesting the passage of the Rebellion Losses Bill. In 1856, as a Brownite Reformer, he endorsed Brown’s vision of Canadian expansion northwest into the Hudson’s Bay Company territory. On 8 Jan. 1857 he participated in the Reform Convention convened by Brown in Toronto to unite disparate Reformers: Brownites in Toronto, Clear Grits in the western part of Upper Canada, and John Sandfield Macdonald*’s supporters in the east. Howland was one of the handful of Toronto professional or business figures, mainly Brown supporters, who were charged with the direction of the Reform Alliance, the organizational body set up to give the party structure.

In the election of 1857–58 Howland won the seat for York West. The Reformers gained a majority in Upper Canada and in August 1858, under Brown’s leadership, they joined with Antoine-Aimé Dorion*’s Rouge minority in Lower Canada to form a ministry that was defeated two days later by the “double shuffle” manœuvre of John A. Macdonald* and George-Étienne Cartier*. This defeat convinced Brown and Howland that only a radical restructuring of the legislative union could circumvent political interference by the governor general (Reformers believed that Governor General Sir Edmund Walker Head* was a partisan Tory) and the legislative predominance of Lower Canada, whose Bleu bloc habitually united with Upper Canadian Conservatives to retain power. Some Reformers, Howland among them, suffered materially from the defeat. In 1858 the North-West Transportation, Navigation and Railway Company, controlled by Howland, Allan Macdonell*, and other associates of Brown, had acquired a contract to carry mail between Canada and Red River (Man.), but in July 1859 the Macdonald-Cartier ministry revoked the contract and gave it to a Conservative mla.

At the Reform Convention of November 1859, held in St Lawrence Hall in Toronto, Howland was one of eight Quakers in an assembly that was mainly Presbyterian and Methodist; he was also one of the many merchants who, along with farmers from the Toronto area and the southwest, made up the majority of the participants. Howland made no speeches at the convention, preferring instead to use his considerable influence behind the scenes. As a representative of York County, he no doubt stood for some kind of legislative dissolution, which found its greatest support in that county. Most delegates resented the commercial dominance of Montreal and the arrangement under union whereby public funds generated in the upper province were used for local improvements in Lower Canada. Howland was a member of the finance committee formed at the convention and, with Brown, William McDougall, Oliver Mowat, Donald McDonald*, and others, mainly from Toronto, he was named to the Constitutional Reform Association, which first met on the final day of the gathering. Its aim was to publicize the convention’s resolutions and to pressure the Canadian parliament into making structural changes to the union in order to give local (provincial) legislatures, which the Reformers hoped to see established, control over all matters except those of “common concern to all Canada.”

During the 1860s Howland’s business interests became increasingly concentrated in Toronto, where he served as president of the Board of Trade in 1859–62. He established a new wholesale produce and milling business there, William P. Howland and Company, and in 1867 the partnership with his brothers at Lambton Mills was dissolved, though they would continue the business there. As well, he became prominent in local insurance companies and banks.

Re-elected in York West in 1861, Howland had soon become intensely involved in ministerial activity. After the Reformers resumed power the following year under John Sandfield Macdonald and Louis-Victor Sicotte*, he was appointed to the Executive Council. He served first as minister of finance, from 24 May 1862 to 14 May 1863, and then as receiver general, to 21 March 1864, when the ministry of Sandfield Macdonald and Dorion resigned. In the autumn of 1862, Howland and Sicotte had joined representatives of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick in London to discuss with the Colonial Office the construction of an intercolonial railway [see Sir Samuel Leonard Tilley*]. The Colonial Office agreed to guarantee a loan, on condition that the provinces create a sinking fund. Recognizing the political folly of proceeding against the Reformers’ commitment to retrenchment, Howland and Sicotte rejected the proviso and negotiations suddenly broke off.

Howland was not part of the coalition ministry formed in June 1864 when Brown joined with John A. Macdonald to push for a federation of British North American provinces. In November, however, a Reformer was needed to replace Oliver Mowat in the coalition and Brown nominated Howland. On the 24th he became postmaster general, a position he would hold until 30 Aug. 1866, when he succeeded Alexander Tilloch Galt* as finance minister. In July 1865 Howland and Galt were sent to Washington to discuss renewal of the Reciprocity Treaty of 1854, but the administration of President Andrew Johnson proved unsympathetic. With William Alexander Henry* of Nova Scotia and Albert James Smith* of New Brunswick, they again went to Washington in January 1866 in one last but unsuccessful attempt to renew reciprocity.

As a member of the coalition ministry, Howland was one of three delegates from Upper Canada at the London conference of 1866–67, which framed the future British North America Act. He thus became a father of confederation, the only American-born founder of the new country. At the conference Howland worried about the power of the projected senate, whose members were to be appointed for life by the governor general. To curb its power over the lower house he suggested that each of the proposed provinces be allowed to appoint senators to fixed terms. It was W. A. Henry’s suggestion, however, that was incorporated into the BNA Act: that the elected government be given the authority to appoint a specified number of additional senators in order to guarantee that the representatives of the people would not be held hostage by the appointed senate.

In June 1867, when Brown convened another Reform convention, Howland and McDougall paid for their refusal to follow him in his withdrawal from the coalition in December 1865: they were expelled from the convention. This turn of events appears to confirm Hector-Louis Langevin’s opinion that Howland was excessively prudent and timid. However, the expulsion may be an indication of his strength of character. Although of a quiet, compromising nature, when occasion demanded it he was capable of standing up to outspoken men such as Brown and Cartier. According to Donald Grant Creighton*, Howland, with Sicotte, stormed out of their meeting with the officials at the Colonial Office in 1862 – not the act of a man easily cowed. In backing Macdonald’s version of a confederation, even though he must have known that his links with Reformers, especially with the followers of Brown, would be weakened, Howland again revealed his fortitude.

For supporting Macdonald, Howland gained considerable political leverage within the coalition. With McDougall, he argued successfully in 1867 that three of the five federal cabinet places from Ontario be filled by Reformers. Elected to the commons for York West, Howland was minister of inland revenue in the first cabinet. The other Ontario Reform ministers were McDougall and Adam Johnston Fergusson* Blair. Westminster also rewarded Howland and McDougall for their support of confederation by appointing them to the Privy Council and by making each a cb on 1 July. After the first session of parliament, his health failing and his effectiveness as a Reformer diminished by his being outside the party, Howland retired on 14 July 1868.

The next day Howland was appointed lieutenant governor of Ontario. In addition to advising the premier (John Sandfield Macdonald) and reporting to Ottawa, he presided at the opening of many of the province’s new institutions, among them the Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario (1868) and the Ontario Institution for the Education and Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb at Belleville (1870); as well, he helped to found the Ontario Institution for the Education and Instruction of the Blind, opened at Brantford in 1872. Howland participated in 1870 in raising a volunteer militia for service at Red River to control Louis Riel* and his supporters. In the early 1870s he also presided at official openings of railways; in November 1873, for instance, he inaugurated the Toronto and Nipissing Railway, which ran northeast from Toronto to Coboconk through farming and lumbering country. Like many of Howland’s own business interests, the line helped to reinforce the central place of Toronto in the life of Ontario. On 11 Nov. 1873, shortly after the opening of the Toronto and Nipissing, Howland retired as lieutenant governor.

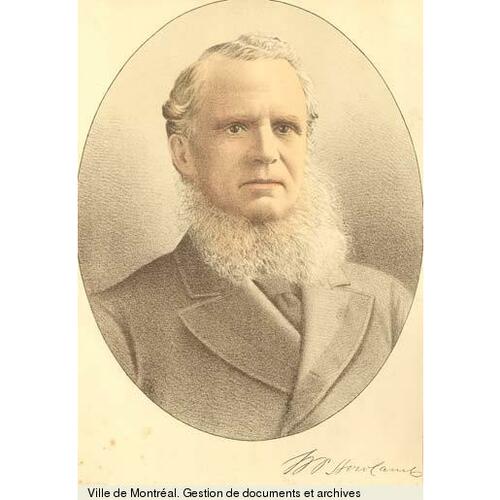

He remained active in public life, however. In 1875 the federal Liberal government of Alexander Mackenzie* made him a commissioner to study the route of the proposed Baie Verte canal across the Chignecto Isthmus. The appointment suggests that, despite his break with Brown and expulsion from the 1867 convention, he remained popular with some Reformers. In recognition of his contributions to Canadian life, he was made a kcmg in May 1879.

Howland also remained active in business. From 1873 to 1902 he was president of the Confederation Life Association, one of the country’s most important financial institutions. In 1878 he rose to the presidency of the Ontario Bank; as well, he was president of the London and Canadian Loan and Agency Company. In December 1880 Howland and other businessmen, most from Ontario, formed a syndicate to build the proposed Pacific railway at less cost than George Stephen*’s Montreal group. The Howland proposal was rejected when the Canadian Pacific Railway Bill went through the commons in January.

In the 1890s Howland began to withdraw from business. Married for the third time in 1895, he soon separated from his wife. In 1906 Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier* suggested that he write an account of his life. Although in declining health at the age of 95, he dictated a lively autobiography. In September 1906, less than four months before his demise, he laid the cornerstone of the new building in Toronto for the National Club, of which he had been a member since its founding in 1874 by members of the Canada First movement [see William Alexander Foster*]. At his death on New Year’s Day 1907, Howland was survived by his daughter and by Lady Howland.

Sir William Howland had been a key player in the political and business history of his adopted country, from the time of his arrival in Upper Canada in 1830 until his death more than three-quarters of a century later in the transcontinental nation that he had helped to create and develop.

[The author is grateful to the Honourable William Howland of Toronto, a grandson of the subject, for providing access to the Howland family tree in his possession. r.b.f.]

In 1906 Sir William Pearce Howland dictated his autobiography. His account was typed in 1933 by his cousin William Ford Howland, who appears to have made some factual changes in it. A photocopy of the typescript is available at AO, F 101, MU 4757, no.9.

AO, F 773, MU 133; F 982, MU 2006, envelope 1, marriages performed by John Jennings, 12 July 1843; RG 22, ser.305, nos.5964, 19441; RG 80-5, no.1895-014769. NA, MG 29, D61: 4143–85. World (Toronto), 2 Jan. 1907. F.-J. Audet, Dictionnaire biographique des gouverneurs, lieutenants-gouverneurs et administrateurs du Canada et de ses provinces, 1604–1921 (2v., s.p., s.d.). Canadian biog. dict. Canadian directory of parl. (Johnson). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Careless, Brown. The causes of Canadian confederation, ed. Ged Martin (Fredericton, 1990). Commemorative biog. record, county York. D. [G.] Creighton, John A. Macdonald, the young politician (Toronto, 1952; repr. 1965). Dent, Canadian portrait gallery, vol.3. DNB. S. T. Fisher, The merchant-millers of the Humber valley: a study of the early economy of Canada (Toronto, 1985). E. H. Jones, “The Great Reform Convention of 1859” (phd thesis, Queen’s Univ., Kingston, Ont., 1971). Ged Martin, “What we know and what we think we know: the coalition of 1864 in the Province of Canada” (paper presented at the annual conference of the British Assoc. for Canadian Studies, Nottingham, Eng., 1991). W. L. Morton, The critical years; the union of British North America, 1857–1873 (Toronto, 1964). Ontarian Genealogist and Family Historian (Toronto), 1 (1898–1901): 148–53. H. F. Pierce, Sir William Pierce Howland, c.b., k.c.m.g., 1871–1907: a bi-centennial tribute to a distinguished American-born Canadian statesman (Plymouth, Mass., 1976). Types of Canadian women (Morgan). P. B. Waite, Canada, 1874–1896: arduous destiny (Toronto and Montreal, 1971).

Cite This Article

R. B. Fleming, “HOWLAND, Sir WILLIAM PEARCE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/howland_william_pearce_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/howland_william_pearce_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | R. B. Fleming |

| Title of Article: | HOWLAND, Sir WILLIAM PEARCE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2024 |