Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

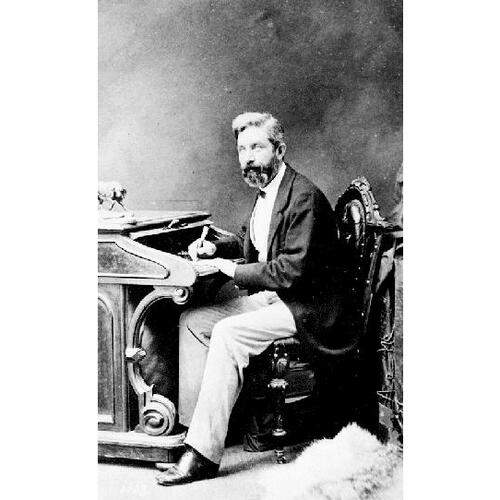

HELMCKEN, JOHN SEBASTIAN, physician, politician, and HBC chief trader; b. 5 June 1824 in London, England, eldest son of Claus Helmcken and Catherine Mittler; m. 27 Dec. 1852 Cecilia Douglas in Victoria, and they had four sons and three daughters; d. there 1 Sept. 1920.

Of German ancestry, John Sebastian Helmcken was educated first at St George’s German and English School in London. He was apprenticed as a chemist and druggist and then as a doctor. In 1844 he became a student at Guy’s Hospital. After his third term he sailed to York Factory (Man.) in the summer of 1847 as surgeon aboard the Hudson’s Bay Company ship Prince Rupert. He returned to Guy’s in the autumn and successfully took the examinations for membership in the Royal College of Surgeons of England in 1848. Eager to see the world, he spent about 18 months on a passenger vessel that sailed to India and China. In October 1849 he obtained employment as a surgeon and clerk in the HBC, to be stationed on the Pacific coast of North America. Shortly after arriving at Esquimalt (B.C.) in March 1850, he was posted by chief factor James Douglas* to Fort Rupert (near Port Hardy), where the company had a coalmining operation. While there he received the first appointment made by the first governor of Vancouver Island, Richard Blanshard*, when in June he was commissioned magistrate to deal with disturbances among the miners [see Andrew Muir*]. Late in the year Douglas moved him to Fort Victoria (Victoria) to be medical officer there.

In 1852 Helmcken married Douglas’s eldest daughter. His new father-in-law was by then the colony’s governor as well as the HBC’s chief factor, and Helmcken thus joined what Amor De Cosmos* would refer to as the “family-company compact.” Like the Douglases an Anglican, he would move with them to the Reformed Episcopal Church at the time of the schism in 1875 [see George Hills*]. He was elected to the first legislative assembly in 1856 and remained speaker of the legislature through the union with British Columbia in 1866 until confederation with Canada in 1871. From 1863 to 1870 he was a chief trader in the HBC and on 1 Jan. 1870 he was appointed to the Executive Council by Governor Anthony Musgrave*. His various offices and connections at times placed him in a precarious political position, but his astuteness and popularity with the voters ensured his survival.

In March 1870, when the possibility of confederation with Canada was being debated, Helmcken declared, “It cannot be regarded as improbable that ultimately, not only this Colony, but the whole of the Dominion of Canada will be absorbed by the United States,” and he was sometimes branded as an annexationist, although he denied the charge. Certainly, he believed that union with Canada had to be “to the material and pecuniary advantage of this Colony.” With Joseph William Trutch* and Robert William Weir Carrall*, he was selected to meet dominion authorities in Ottawa for a discussion of terms. He was pessimistic about the practicality of union because of the extraordinary distances involved, and he was determined, therefore, to make the transcontinental railway a sine qua non of British Columbia’s entry into confederation. He also demanded that the Canadian system of tariffs not supplant the colony’s more protective structure until completion of the railway. Canada’s willingness to put into the terms of union a promise to begin the railway within two years, and complete it within ten, made Helmcken into a supporter of confederation, although he apparently remained unconvinced of the merits of responsible government, which was to be introduced in the new province. His position on tariffs, agreed to at the negotiations, would be the main issue in the first provincial election and would be narrowly rejected by British Columbians.

With entry into Canada secured in 1871, Helmcken retired from public life to devote time to his medical practice. In recognition of his contribution to colonial politics and pivotal role in the confederation debate, he was offered the positions of senator, provincial premier, and, later, lieutenant governor, all of which he declined. He did accept a directorship with the Canada Pacific Railway Company, and he remained a staunch supporter of Sir John A. Macdonald*’s Conservatives throughout the period of the Pacific Scandal.

During British Columbia’s crucial early years in confederation, Helmcken worked behind the scenes for the benefit of Vancouver Island and Victoria. He had been instrumental in having the capital moved to Victoria from New Westminster, against the wishes of the mainland, and his great influence in private and public circles advanced the city’s interests immeasurably, both in political terms and in the awarding of federal public-works contracts. With the rise to power of Alexander Mackenzie*’s Liberal party late in 1873, however, the start of railway construction in British Columbia was seriously delayed, and Helmcken’s preferred choice of a route to Esquimalt via Bute Inlet fell into disfavour as the influence of mainland interests grew.

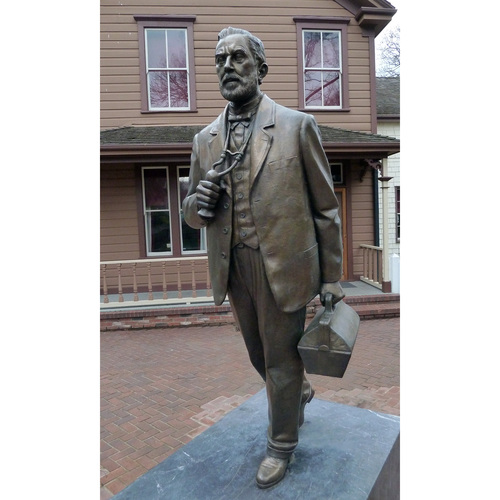

Helmcken remained a respected public figure throughout his later years. Surgeon to the HBC from 1870 until 1885, he was a founding president of the British Columbia Medical Association in 1885 and his influence led directly to the establishment the next year of the Medical Council of British Columbia, the licensing body for the province’s doctors. He was president of the board of directors of the Royal Hospital (from 1890 the Royal Jubilee Hospital) in Victoria and, from 1851 to 1910, physician of the provincial jail. Until his death in 1920, he lived in the house which he had built for his new bride in 1852 (and which is now a museum).

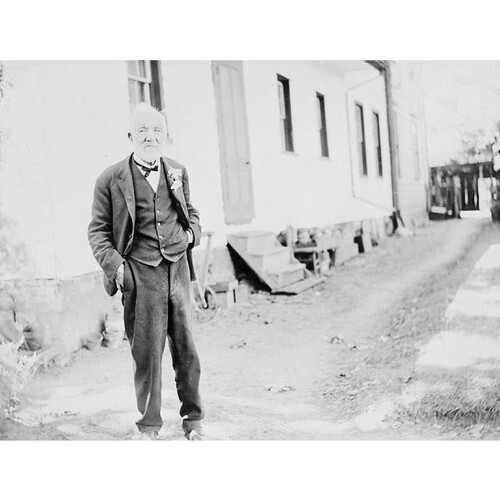

Historian Hubert Howe Bancroft interviewed Helmcken in 1878 and describes him as a man “short and slightly built . . . with deep, clear, intelligent eyes, in which there was self-confidence and critical discrimination, but no malice . . . and given to much laughter.” (Helmcken thought less well of Bancroft.) His patients evidently liked him. Painter Emily Carr* remembered from her childhood that “you began to get better the moment you heard Dr. Helmcken coming up the stairs.” Helmcken said of himself that he was “friendly with everyone . . . but curiously enough never had any intimate friend.” In his old age he set down his reminiscences up to the time of confederation, and through them and the voluminous papers that he left, he has remained a living presence in the history of British Columbia.

Helmcken’s memoirs were published as The reminiscences of Doctor John Sebastian Helmcken, ed. Dorothy Blakey Smith, intro. W. K. Lamb ([Vancouver], 1975), and “Helmcken’s diary of the confederation negotiations, 1870,” ed. W. E. Ireland, appears in British Columbia Hist. Quarterly (Victoria), 4 (1940): 111–28. His papers are preserved in BCARS, Add. mss 505.

British Colonist (Victoria), 1858–60, continued as the Daily Colonist, 1860–99. Victoria Daily Standard, 1870–88. Victoria Gazette, 1858–59. H. H. Bancroft, History of British Columbia, 1792–1887 (San Francisco, 1887). B.C., Legislative Council, Debate on the subject of confederation with Canada (Victoria, 1870; repr. 1912). Emily Carr, The book of Small (Toronto and London, 1942). R. E. Gosnell, “Doctor Helmcken,” Man to Man (Vancouver), 7 (1911), no.1: 28–30. G.B., Parl., House of Commons papers, 1867/68, 48, no.483: 337–50, Copy or extracts of correspondence . . . on the subject of a site for the capital of British Columbia; 1868/69, 43, no.390: 341–71, Papers on the union of British Columbia with the Dominion of Canada. J. E. Hendrickson, “The constitutional development of colonial Vancouver Island and British Columbia,” in British Columbia: historical readings, ed. W. P. Ward and R. A. J. McDonald (Vancouver, 1981), 245–74. Journals of the colonial legislatures of the colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia, 1851–1871, ed. J. E. Hendrickson (5v., Victoria, 1980). H. M. Kidd, “Pioneer doctor John Sebastian Helmcken,” Bull. of the Hist. of Medicine (Baltimore, Md), 21 (1947): 419–61. D. P. Marshall, “Carnarvon terms or separation: B.C., 1875–78,” British Columbia Hist. News (Victoria), 26 (1993), no.3: 13–16; “Mapping the political world of British Columbia, 1871–1883” (ma thesis, Univ. of Victoria, 1991). M. A. Ormsby, British Columbia: a history ([Toronto], 1958). W. N. Sage, “The critical period of British Columbia history, 1866–1871,” Pacific Hist. Quarterly (Glendale, Calif.), 1 (1932): 424–43. Scholefield and Howay, British Columbia, vols.2–3. Brian Smith, “The confederation delegation,” in British Columbia & confederation, ed. W. G. Shelton (Victoria, 1967), 195–216.

Cite This Article

Daniel P. Marshall, “HELMCKEN, JOHN SEBASTIAN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 22, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/helmcken_john_sebastian_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/helmcken_john_sebastian_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Daniel P. Marshall |

| Title of Article: | HELMCKEN, JOHN SEBASTIAN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | January 22, 2025 |